In response to:

Egypt: The New Dictatorship from the June 8, 2017 issue

To the Editors:

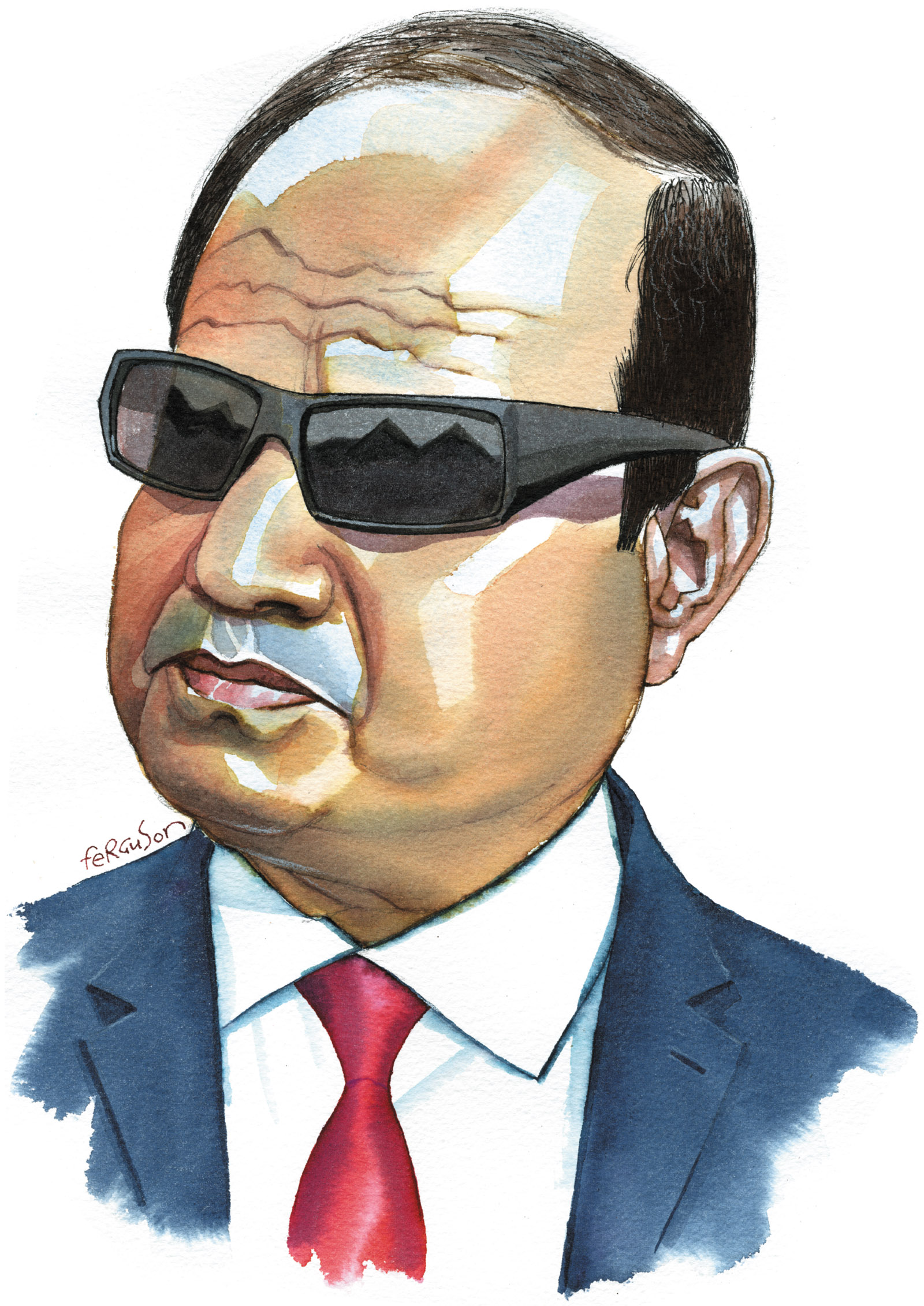

I appreciate Joshua Hammer’s thoughtful review of my book, The Egyptians: A Radical History of Egypt’s Unfinished Revolution [“Egypt: The New Dictatorship,” NYR, June 8], and more importantly the space given over to highlighting some of the many aspects of Egypt’s current plight. Emboldened by international support, both political and financial, the dictatorship of former General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi continues to intensify its crackdown on all forms of opposition and dissent. In addition to its penchant for forced disappearances, its effective outlawing of unsanctioned protests, its unprecedented crackdown on civil society, and its ongoing epidemic of state torture—one that local human rights campaigners say is the worst in Egypt’s modern history—Sisi’s regime is currently targeting online media outlets that dare to question official narratives; at the time of writing, the number of websites blocked has reached 64.

But Hammer grossly mischaracterizes my work when he asserts, in answer to his question “Why did the revolution fail?,” that “Shenker places the blame squarely on the [Muslim] Brotherhood.” In reality, the book looks back to the origins of the contemporary Egyptian state in an effort to explain why a particular elite and exclusionary political model with the military at its helm has proved so resilient inside the Arab World’s most populous nation, and names a number of different forces—including, significantly, international financial institutions and some Western governments—as being responsible for trying to shield that model from the revolution’s storms. By refusing to ally itself to revolutionaries in the critical period following Mubarak’s downfall in early 2011 and in its attempt to crush many forms of revolutionary activity once it secured the presidency in 2012, the leadership of the Muslim Brotherhood certainly helped make space for the counter-revolution, but they were one element of a much larger and complex mosaic. As the book also makes clear, within a long and varied list of victims under Sisi it is ordinary supporters of the Brotherhood—gunned down in their hundreds by security forces during the Rabaa massacre of August 2013—that have suffered most directly.

This error matters because at the heart of Egypt’s revolutionary struggle lies a battle over history: over who can lay claim to the enormous blossoming of popular sovereignty that began to transform Egypt and the world beyond its borders back in 2011, and which could yet erupt again. “Blame” for the violence which has been inflicted upon Egyptian civilians by a succession of autocrats belongs first and foremost to the autocrats themselves; not far behind stand those in foreign capitals who continue to sell billions of dollars of weaponry to them, and who insist—as President Trump did during his Egyptian counterpart’s visit to the White House earlier this year—that Sisi is doing “a tremendous job.” Meanwhile please spare a thought for our Egyptian reporter colleagues, many of whom sit behind bars or are prevented through intimidation from doing their work, and yet whose determination to persist and to bear witness should be an inspiration to us all. “We are the children of margins,” wrote the editorial team behind Mada Masr, an independent Egyptian news outlet that is among those currently being censored in Egypt, “from there we emerge and re-emerge.”

Jack Shenker

London, England

Joshua Hammer replies:

There were indeed plenty of other forces responsible for bringing down the revolution, notably the Egyptian military and the “deep state”—along with some leading liberal voices themselves, as I noted in my piece—and Shenker makes that case in great and persuasive detail. My observation that Shenker placed the blame “squarely” on the Brotherhood was meant to counter the sentence that came right before it: that many accused the military of deliberately sabotaging the Morsi government. Shenker offers a counterargument by pointing out that the Brotherhood was its own worst enemy, and that the brutality and autocratic ways of its leadership contributed greatly to its profound unpopularity, and the turning of public opinion against it. I did not mean to suggest that the Muslim Brotherhood alone was responsible for the death of the Egyptian Revolution, nor do I believe that Shenker thinks this.

This Issue

April 18, 2024

The Corruption Playbook

Ufologists, Unite!

Human Resources