The author, a retired US Foreign Service officer, served as US Ambassador at Large for Counterterrorism between 1994 and 1997.

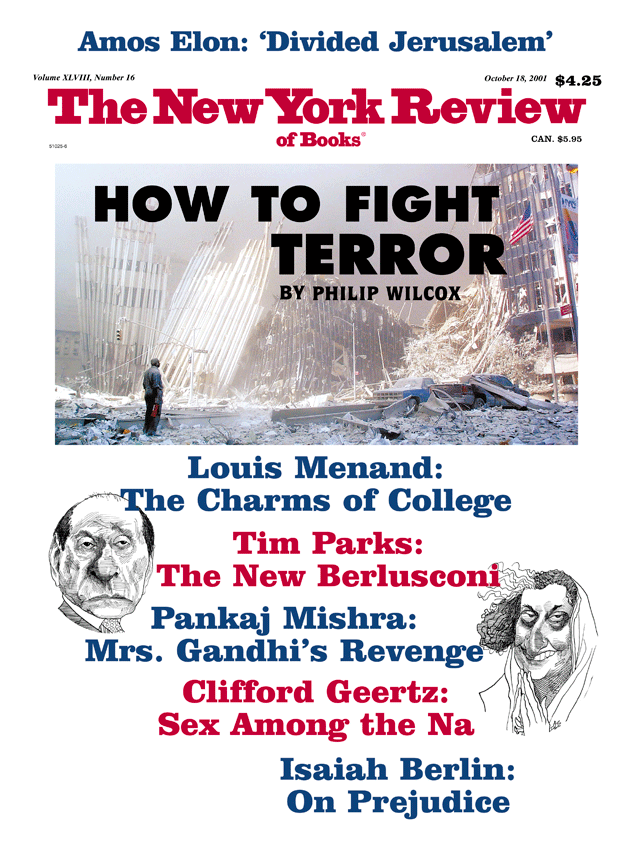

The Bush administration has declared “war” against terrorism, suddenly shocked into realizing that it is now the foremost danger to America’s national security. The administration has not yet defined this war, although a head of steam is building for military action. Armed force, however, while politically popular, is usually an ineffective and often counterproductive weapon against terror. Before acting, the US would be wise to construct a more sophisticated strategy. This should include strengthening traditional methods of counterterrorism, while reserving the use of force as a limited option. But a new national security strategy must also include a broader foreign policy that moves away from unilateralism and toward closer engagement with other governments, and that deals not just with the symptoms but with the roots of terrorism, broadly defined. The catastrophe of September 11 could give powerful momentum to such changes.

Islamist terrorists, who are thought to be responsible for the September 11 attacks, were first identified by analysts as the main terrorist threat to the US after a similar, although less sophisticated, gang carried out the first attack on the World Trade Center in 1993. These terrorists, so far as we know, are not sponsored by states; they have been recognized as posing a more complex and lethal challenge than state sponsors of terrorism, such as Libya, which are now mostly inactive, or anti-American secular terrorist groups, which are practically all moribund.

The deep hatred and suicidal fanaticism of the Islamist terrorists, their lack of a rational political calculus, and their belief in divine sanction make the penalties and deterrents traditionally used against terrorists far less effective. It is difficult for intelligence agencies to penetrate their cells, which are loosely structured and often act on an ad hoc basis, and therefore are extremely hard to identify and keep under surveillance. Porous borders, fake documents, and sympathizers who offer cover in a great many countries give such terrorists global mobility. Worst of all, as analysts have predicted and the horror of September 11 confirmed, Islamist terrorists seek mass casualties, and are heedless of public opinion and conventional morality. Searching for a pattern in this maze, US analysts believe Osama Bin Laden is the mastermind of a global network of fanatic Islamists and the prime suspect behind the September 11 attacks.

Some of President Bush’s civilian advisers want a tough new policy of military retaliation and preemption of terrorism, in place of tedious and uncertain criminal prosecution, the preferred policy of the Clinton administration. Bush himself seems to believe that a dramatic military effort could be a popular catharsis for public outrage and demands for action.

But on the rare occasions that the US has tried to carry out military attacks on terrorist targets, the attacks have failed or backfired. The US bombing of Tripoli in 1986, after a Libyan terrorist attack on Americans in Germany, killed dozens of Libyan civilians. Qaddhafi struck back in 1988 by bombing Pan American Flight 103, killing 270 people. Also, US cruise missile attacks on targets in Sudan and Afghanistan after the bombing of American embassies in East Africa in 1998 had no discernible effect on terrorism and provoked widespread international criticism.

In contrast to Bush’s civilian hawks, many American military officers are skeptical about using military force against terrorists. They point out that a target like Bin Laden, who is thought to be hiding in the mountains of Afghanistan, probably could not be hit from the air and that his physical “infrastructure” is negligible. Moreover, abducting or killing him with US ground forces, especially in such a remote and hostile environment, presents grave intelligence as well as tactical and logistical challenges. A better approach would be a concerted international effort, with carefully calculated pressures and incentives—and cooperation from Pakistan, which is essential—to persuade Bin Laden’s Taliban hosts to hand him over for trial. He is already under a previous US indictment. Bombing the Taliban to make them give up Bin Laden might kill innocents and would probably fail.

The use of military force is questionable for other reasons. Islamist terrorists throughout the world seek death through martyrdom. Far from deterring these self-proclaimed holy warriors, US military attacks would likely inspire them to carry out even more dangerous acts of terrorism; the effect could well be to increase recruitment and raise the stature of the terrorists in the underworld of militant Islam. Without minimizing the threat they pose, we should regard these people as criminals and murderers, and not dignify them as warriors. We must also understand that getting rid of Bin Laden will eliminate neither the ideology of Islamist terrorism nor its often inchoate and diffuse operations.

At the same time, using military force against terrorists in sovereign foreign states is likely to raise difficult legal issues. Unilateral attacks may violate international laws, including treaties against terrorism that the US has worked hard to strengthen; and they may alienate governments, especially in the Islamic world, whose cooperation we need. Although NATO governments have pledged solidarity with the US after the September 11 attacks, some have already expressed wariness about an American military intervention or attack. In any case, if the US government cannot show a clear evidentiary trail of foreign direction of the September 11 attacks, using military force will not be a credible strategy, especially since many of the terrorists and suspected terrorists, who came from several countries, have lived in the US, and at least some of the training and planning for the attack took place here.

Advertisement

If a military solution is not advisable, what can be done to minimize the risk of further disasters? Improving aviation security should clearly be the first step. Because aircraft hijacking had virtually stopped during the past decade, US analysts no longer concentrated on this threat, much less on the nightmare of using hijacked aircraft as suicide bombs against mass civilian targets. After the bombing of Pan American 103, US officials knew that the additional measures that were then taken to strengthen aviation security were hardly foolproof. But they were looking at other mass threats, like the use of chemical and biological weapons, and were reluctant to provide more funds; the airlines prevailed in arguing that more effective security would be too costly for them and too unpopular.

Intelligence and analysis should also be improved; but there are limits to our ability to collect intelligence abroad, especially in hard-to-penetrate terrorist networks. In the US, where some of the training and planning for the recent attacks might have been discovered and preempted, the FBI is constrained by constitutional limits on eavesdropping and on other intrusive measures. A debate is already underway about whether these protections have now become a luxury that Americans cannot afford. Many will be loath to sacrifice these freedoms. Citizens and politicians must accept the grim reality that while we can do more to prevent further catastrophes, terrorism in open societies can never be eliminated entirely. We must also be prepared for the possibility that, even as we improve intelligence and aviation security, terrorists will adopt new tactics, perhaps using weapons such as chemicals and biotoxins and striking at other vulnerable targets.

The most important deficiency in US counterterrorism policy has been the failure to address the root causes of terrorism. Indeed, there is a tendency to treat terrorism as pure evil in a vacuum, to say that changes in foreign policy intended to reduce it will only “reward” terrorists. Moreover, many argue that terrorists care little about particular American policies and hate the US simply because it is powerful, rich, modern, and democratic and because its dynamic secular culture threatens their identity.

But the US should, for its own self-protection, expand efforts to reduce the pathology of hatred before it mutates into even greater danger. Conditions that breed violence and terrorism can at least be moderated through efforts to resolve conflicts and through assistance for economic development, education, and population control. Limiting the proliferation of lethal materials also deserves higher priority as a measure against terrorism as well as for arms control.

The US must also realize that, notwithstanding our great power, indeed because of it, we cannot dictate respect and cooperation. Other nations will not fully help us in combating terrorism, whatever pressures we apply, unless we are sensitive to their legitimate interests and are willing to reciprocate. Certainly the US should reappraise its policies concerning the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and Iraq, which have bred deep anger against America in the Arab and Islamic world, where much terrorism originates and whose cooperation is now more critical than ever. We can do all this without abandoning our basic commitments, including to the security of Israel.

We should also search for ways to strengthen the common bonds between Western values and Islam to combat the notion of a “clash of civilizations” and to weaken the Islamist extremist fringe that hates the West and supports terrorist actions. Such new departures in US foreign policy would require devoting far greater resources to support a more engaged, cooperative, and influential American role abroad. Redefining national security and counterterrorism in this broader sense is the most promising way to fight the war against terrorism. It is vital that we do this soon, now that the stakes have been raised so high.

—September 19, 2001

This Issue

October 18, 2001