1.

The opening shots of Clint Eastwood’s Mystic River are clipped and simple: a city by a river (South Boston, serving here as archetype of the post-industrial American city as faded remnant); a second-floor porch in a neighborhood that has seen better days, where two men drink beer and talk about sports; the street below where three young boys are playing. A moment later a car will pull up and—with the kidnapping of one of the boys by two pedophiles masquerading as a cop and a priest—inaugurate a cycle of violence that takes the rest of the movie to play itself out. Little of the violence will appear on screen, yet its presence will be felt in virtually every frame: we will be reminded at each instant of the memory, the dread, the threat, or the lingering aftermath of violence, the residue of psychic pain that will nurture some fresh evil. Victims will become victimizers, and victimizers themselves come to be seen as the helpless agents of a destiny just beyond their control.

The abruptness of the opening establishes the tempo for everything that follows. We have hardly registered the place and the players—the three boys, Jimmy, Sean, and Dave, horsing around aimlessly, carving their names in a freshly cemented sidewalk—before we, and they, are interrupted. There is scarcely time for our adult sense of danger to kick in before young Dave (visibly the least self-assured of the three) has allowed himself to be ordered into the car by the false cop, ostensibly to be reprimanded for vandalizing the sidewalk. There is a fraction of a second to notice the trash piled in the back of the vehicle—and by then the car is speeding away down the block. Dave, disappearing into the distance, looks out the back window at his friends while they stand by helplessly. The film cuts immediately to a very brief scene of Dave, held prisoner in a dark basement, recoiling as one of his abusers comes down the steps for another round; cuts again, as abruptly, to Dave running through woods as he escapes his captors; and finally shows a muted street scene of the neighbors, including the other two boys, looking on as the expressionless Dave is restored to his mother.

The prologue ends; decades pass in a blink, and we find ourselves in the same neighborhood, scarcely changed, where we meet one by one the grown-up boys. Jimmy (Sean Penn), whose flare of cocky resistance saved him from Dave’s fate, is a reformed thief who, after a prison term, has become the proprietor of a corner grocery; Sean (Kevin Bacon), who was saved because he told the abductors that his parents lived on that block, has succeeded in becoming a police detective but is separated from his wife and visibly troubled; and the unfortunate Dave (Tim Robbins), who has a wife (Marcia Gay Harden) and a son, as well as an air of depression beyond words. We come to know them on the run, as it were, as each in turn is caught up in a second tragedy: the murder of Jimmy’s daughter is investigated by Sean, and suspicion gradually settles on Dave. Dave, we will ultimately learn, has in fact committed a murder, an entirely unrelated and in some sense justifiable one; but betrayed by appearances and other peoples’ assumptions, he will end up dropped into the river of the title, victim of misguided vengeance.

What’s impressive is how steadily the beats fall from the start, and how rigorously they are sustained. For a film concerned almost exclusively with the grimmer and more despondent aspects of human experience—we will see Dave abducted and abused, Jimmy’s daughter murdered, Jimmy overwhelmed by grief and undertaking a futile vengeance, Dave’s wife losing all trust as she watches her husband disintegrate, the more or less innocent Dave lured to his doom, and his young son acquiring his father’s damaged mien—Mystic River moves at something of a clip: but it is an oddly somber kind of clip. Compressing a long, crowded, and intricately plotted novel by Dennis Lehane into 137 minutes, as the screenwriter Brian Helgeland has skillfully done, necessitated a certain speed of exposition. Lehane’s novel takes over four hundred pages to establish a social milieu and a detailed psychological profile for each character; Helgeland often has no choice but to reduce pages of the background story to a single line of dialogue, so that we’re learning about a character’s past at the very moment that his future is emerging. Eastwood’s feeling for tempo and emotional tone keeps these densely packed scenes from collapsing into a mere ticking-off of plot elements.

The rhythm is calmly relentless. Events occur in a measured and inexorable way, and each event generates convergences whose consequences unfold without allowing us time to pull back and see them in perspective. There is none of that false action-movie urgency that forces a sense of involvement by goading the spectator along with optical dazzle and booming bass lines; but there is an accumulating vertiginous sense of events tumbling methodically beyond any point of return. That early shot of the abducted child staring out the rear window of the car carrying him to his own designated hell establishes what will be the rule of this story: that by the time we grasp what has happened, it will be too late to intervene.

Advertisement

At the same time, no concession is made to the equally prevalent heartswelling counter-impulse to suspend time to milk moments of grief and anguish for all they’re worth. Such moments occur with terrible frequency in Mystic River, as when Jimmy and his wife, Annabeth (Laura Linney), attempt to console each other in an anteroom of the morgue where their daughter lies, or when Dave’s wife, who has seen her husband come home bloodied on the night of the murder, begins to formulate her doubts about him; worst of all, the moment when she spills those doubts to the enraged and reckless Jimmy. It would have been tempting to prolong and heighten each such episode to tear-jerking effect; but here no pause is provided for that kind of indulgence. At the particularly harrowing point where Sean Penn fights his way through a line of police toward his murdered daughter’s body, the camera pulls up and away from Penn’s anguish into an aerial view of the whole scene, not so much to mute his grief as to suggest the wider setting in which that grief will wreak devastation. The film doesn’t surge toward emotional high points but rather sustains one steadily deepening note.

The interlocking lives with which Mystic River concerns itself constitute a labyrinth without an exit. The claustrophobic convergences of Dennis Lehane’s narrative are if anything accentuated in the film version. In the novel, there is a layer of interior monologue elaborating each character’s motives and reactions, and this provides if not comfort then at least some sense of emotional privacy, a buffer zone of language. By stripping away most of the words, the movie leaves us with the bare plot structure, but this turns out to be a refinement rather than a reduction. If the compression risks exposing the implausibility of certain coincidences (such as the two murders, of Jimmy’s daughter and of the child molester killed by Dave, that turn out to have occurred almost simultaneously), it also redoubles the chilly austerity of Lehane’s moral geometry: the deeds are cut free from explanatory words.

That strict geometry makes Mystic River rather different from Eastwood’s other films, which have tended toward lankier, more episodic structures. He has the reputation of being a director who likes to make decisions quickly—who rarely subjects scripts to successive rewrites, and who prefers to nail a scene on the first or second take—and his films exude at best the freshness of focused spontaneity. In taking on a tightly organized narrative with more than a dozen pivotal characters, he has challenged his own resources as a director and met the challenge with tremendous success.

If Eastwood has for once chosen to sign the film’s music himself—the simplicity of the plangent title theme serving to offset, or perhaps rein in, the careening of the plot—it is perhaps to emphasize the musical character of his approach to direction. After the superb solos and duos of many of his previous films, he has here realized a stunning work for ensemble. The rhythmic sureness instills from the outset a sense of dread. The dread is not of a particular horror; it’s rather the growing presentiment that the world as it is to be shown here will reveal its essential pitilessness. The car that went down the street after capturing Dave is still running; it was always too late to undo what had been set in motion. Mystic River stares long enough at the irreversibility of what happens to induce something like grief, a grief felt equally for all its characters.

What is most impressive about Mystic River is the equal importance assumed by each scene and character in turn, even those that might for a moment seem digressive or incidental. The hinges that take us from one moment to the next are physical actions of the most ordinary kind: someone getting into a car, looking out a window, having a drink in a bar, minding the till in a small store. If while watching Mystic River I sometimes thought of D.W. Griffith, it’s because Griffith had the same capacity to make ordinary American streets and spaces seem like mythic sites as ancient as Babylon, and the same sense of how easily those spaces could be reconfigured by an accidental turn of events into traps, barriers, targets for invasion, stages for rituals of mourning or outbursts of madness.

Advertisement

A cul-de-sac in a riverside park becomes a killing ground; the retrieval of a hidden past is signaled by a hand groping for a revolver in an attic storage space; a front stoop serves as the stage for a conversation that triggers a revenge killing; and a ramshackle tavern with a back door conveniently opening on a deserted stretch of waterfront will be the site of an execution. The drab places acquire a taint from what has happened in them. The Irish-American neighborhood where the film is set seems a remnant of that earlier America of Griffith, with its tightly knit clans, bands of local toughs with their codes of silence, and uneasy relations between those who enforce the law and those who break it. Mystic River is a work of interlocking parts in the same way that Intolerance was, and its various parts are in constant movement.

The formal structures are analogous to the social structures that constrict the characters. The editing takes us from one microworld to another with no transitional beats—there isn’t time—and it’s as if all these worlds are in remote contact with one another, tavern and church and funeral parlor, kitchen and crime scene and deserted riverfront. It hardly matters which street a character walks down or which doorway he enters; he will find himself caught up in simply another corner, another phase of the pervasive inescapable narrative. The individual performances here—not merely by Sean Penn, Kevin Bacon, Tim Robbins, Laura Linney, Marcia Gay Harden, and Laurence Fishburne, but by a large cast of supporting actors—are remarkable in themselves, but none is a star turn; the power of the film is in the architecture that frames the performers and establishes relations among them.

Even if the cops talk on cell phones and even if Dave begins finally to become unhinged while losing himself in a vampire movie he’s watching on TV, Mystic River elaborates a world where people find it impossible to change the channel on their reality, or navigate a way out of the streets and houses that bind them to one another in ways that come to seem dictated by fatality. To convey an impression of real bodies moving through real spaces, of lives impinging on one another within a clearly defined geography and system of kinship, doesn’t seem like such a tall order for a filmmaker, but as movies, in the age of unlimited morphing and digitally created images, aspire more and more toward the condition of animated films, the effect becomes increasingly exotic.

It isn’t really surprising that Clint Eastwood should be the one to offer such a restorative. While Mystic River has received a critical approval that Eastwood’s other recent films (Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, True Crime, Space Cowboys, Blood Work) largely did not, it is not anomalous if seen in relation to the deeper currents of his career. Its success may recall how singular that career has been, and how unforeseeably Eastwood has made for himself a world apart, where he can practice an aesthetic often deliberately at odds with the mood of that same pop culture in which he has figured as a star for so many years. When Blood Work—another adaptation of a novel by a first-rate crime writer (Michael Connelly), featuring the same screenwriter and the same cinematographer as Mystic River—opened a year ago, it seemed somewhat like a fugitive from a different zone of filmmaking in which time had stood still.

Blood Work was a movie that one could imagine opening in a world that no longer exists, the 1950s world of drive-ins and neighborhood movie theaters showing pictures by Eastwood’s directorial mentor Don Siegel and a host of other survivors of the old Hollywood—Phil Karlson or Gordon Douglas or André de Toth—a world that was already ending just when Eastwood began his movie career. It may not have been a great movie (its central device of a cop hunting for the murderer of a woman whose heart he received in a transplant operation seemed too schematic), but there was something moving about how resolutely it proclaimed Eastwood’s intention to follow the stylistic path he had chosen so long ago, no matter how anachronistic it might end up looking.

In thinking about Clint Eastwood it helps to bear in mind the extent of the body of work associated with him. He has directed twenty-four features (including only four in which he does not also star). Before directing his first film he had already (subsequent to his long run as a regular on the TV western Rawhide) starred in ten films, of which three were directed by Sergio Leone and three by Don Siegel; subsequently he starred in two more by Siegel, as well as eleven by other directors: forty-seven films in all over a period of roughly forty years (Eastwood was thirty-four when he embodied the Man With No Name in Leone’s primordial spaghetti western A Fistful of Dollars (1964), forty of them produced under the aegis of Eastwood’s own production company Malpaso.

Turn on the TV in Albany or Tampa or Nantes or Nagoya and you will not be surprised at being plunged into Magnum Force (1973) or The Eiger Sanction (1975); walk into any retail outlet where videos and DVDs are sold and you are likely to find more than a fistful of entries in the multivolume Clint Eastwood Collection. The plenitude of his oeuvre harks back to the era of directors who, like Raoul Walsh or Michael Curtiz, moved rapidly from one project to another without getting bogged down in the project development, fund-raising, and marketing strategies without which it is increasingly hard for a film to get made or released. That Eastwood can carry on with an approach that for most filmmakers became untenable with the decline of the studio system is explained in the first place by his having had under permanent contract a bankable movie star: himself.

2.

He was an almost accidental icon before he was anything else. Eastwood emerged on American movie screens at the end of the 1960s; because of legal difficulties, the 1964 Fistful of Dollars and its follow-up For a Few Dollars More did not open in the US until 1967, along with the third and most elaborate of the trilogy, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, by which time he was already a cult figure in Europe. The Leone spaghetti westerns brought a spirit to movies that changed them permanently, accustoming audiences to anti-heroic irony and sardonic cruelty, the deliberate recycling and debasement of old movie conventions, the flaunting of stylization for its own sake. As the laconic hero of those films—a man without a past whose “goodness” (in relation to his “bad” and “ugly” co-stars) is strictly relative—Eastwood was the still, almost wooden figurine at the center of a swirl of self-conscious flamboyance.

The initial impression was not so much of an actor as of a comic book character (from a European comic book at that) come to life. The most striking aspects of Eastwood’s appearance in the Leone films—the stubble of beard, the chewed-up cigarillo, the dusty poncho—were graphic in their impact; all he had to do was stand there. The point was underscored by the minimalist quality of his acting, of which one retained chiefly the unwavering coldness of the gaze and the half-whispering hoarseness of the vocal delivery. Flanked by such histrionic performers as Gian Maria Volonté and Eli Wallach, Eastwood held his own through stubborn restraint.

The spareness—or, to put it another way, the poverty—of the actorly devices that Eastwood enlists in his early roles becomes a form of perverse strength. The voice’s modulations are so slight that the distance between a tone of tenderness and a tone of menace barely registers on the ear. The smile could as easily be deceptive as candid. The closed mouth expresses feeling through a tightly controlled twitching that ranges from the little smirk of hidden knowledge (as when the criminal hero of the 1974 Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, disguised as a preacher, tells his flock that “the true Christian is of a meek and forgiving nature”) to the Dirty Harryish snarl that can convey fear, rage, bewilderment, or a mixture of all three.

The eyes, first and last, continue to be his most powerful means of communication—but what exactly that squinting glance communicates remains ambiguous. In the beginning, Eastwood figured on the screen less as a consciousness than as a somewhat mysterious object—a Zen-like embodiment of action itself perhaps, driven by no readable motive—to be deployed by directors as different as Leone and Siegel for their own expressive ends.

But to contemplate how he himself has used that resource is to register just how his career differs from that of earlier action stars who could fall back on standard gestures and standard plots to sustain long-running careers. Gene Autry or Roy Rogers could essentially make the same movie over and over; John Wayne, while he stretched himself remarkably under the guidance of John Ford and Howard Hawks, usually didn’t go out of his way to disturb audience expectations about what kind of movie or performance they were going to see. Eastwood has followed a more unpredictable and challenging path, sustaining his own star image while at times seeming to question its implications.

Just how much ground Eastwood had covered became apparent in an extraordinary series of films made in the Nineties: White Hunter, Black Heart (1990), an adaptation of Peter Viertel’s novel about the making of The African Queen in which Eastwood undertook the part of John Huston (here, “John Wilson”); Unforgiven (1992), the downbeat western that attracted more critical enthusiasm than any of his previous films; A Perfect World (1993), a drama about a sympathetic but damaged escaped convict which veered into increasingly unexpected emotional territory; and The Bridges of Madison County (1995), a surprising transformation of a treacly best seller into a rigorously pared-down diagram of a love affair.

These are all movies that work in original ways, but they don’t announce their intentions flagrantly. White Hunter, Black Heart, for instance, simply plunges into its film à clef chronicle of Huston’s African odyssey without ever clearly establishing its attitude toward its protagonist, played by Eastwood in a variation of his usual persona sufficiently stylized to make it strange: we are conscious of both mask and face, a distancing effect curiously appropriate for a movie in which one famous movie director mimes the role of another famous movie director. It is a performance with no sense of interiority—“John Wilson,” it appears, cannot look at himself, can only define himself through energetic action, whether admirable (standing up to an anti-Semitic aristocrat, fighting for his artistic independence) or pointlessly destructive (insisting on an elephant hunt that will lead to the needless death of an African tracker). With the questioning of the hero everything else is called into question; the film becomes a series of vivid yet detached episodes whose uneasy lurches and shifts of identification begin to seem remarkably lifelike—that is to say, arbitrary in incident and morally indecipherable in their deeper import.

The ambivalent treatment of the hero, the chipping away at any tendency to identify with Eastwood’s own character, is curious in light of the way Eastwood himself has sometimes been typecast as a moral absolutist of the crudest kind. The antipathy of many critics was crystallized by Pauline Kael’s attack on the 1971 Dirty Harry (directed by Don Siegel) as a “fascist” movie, and it was around that time that Eastwood inherited John Wayne’s status as the all-purpose emblem of the American macho action hero. In fact, even the much-maligned Dirty Harry was a character study of some complexity alongside a straight-out call to vigilantism like Michael Winner’s Death Wish (1974), and in later years Eastwood’s movies rarely achieved the satisfying showdown of the classic action picture.

In the thriller Tightrope (1984),* Geneviève Bujold tells the New Orleans cop played by Eastwood: “I’d like to find out what’s underneath the front you put on,” and there’s a sense that Eastwood (as observer of his actorly self) would like to find out too. The plot of the movie involves the hunt for a serial killer whose victims are prostitutes, but it gets sidetracked interestingly into a consideration of the cop’s troubled domestic life and taste for kinky sex. As we watch him watching two women mud-wrestling by murky red bar-light, the thriller seems no more than a pretext for a detached contemplation of the actor’s blankly riveted face. The more ambitious of Eastwood’s movies undercut any facile sense of moral judgment or moral order. Characters like the movie director in White Hunter, Black Heart or the escaped convict played by Kevin Costner in A Perfect World—or for that matter Sean Penn’s avenging father in Mystic River—exist in a moral free fall in which questions of justification and non-justification lose their meaning but in which, as partial compensation, the world is revealed to them in all its anarchic possibilities: the landscape that stretches out behind or beyond the law.

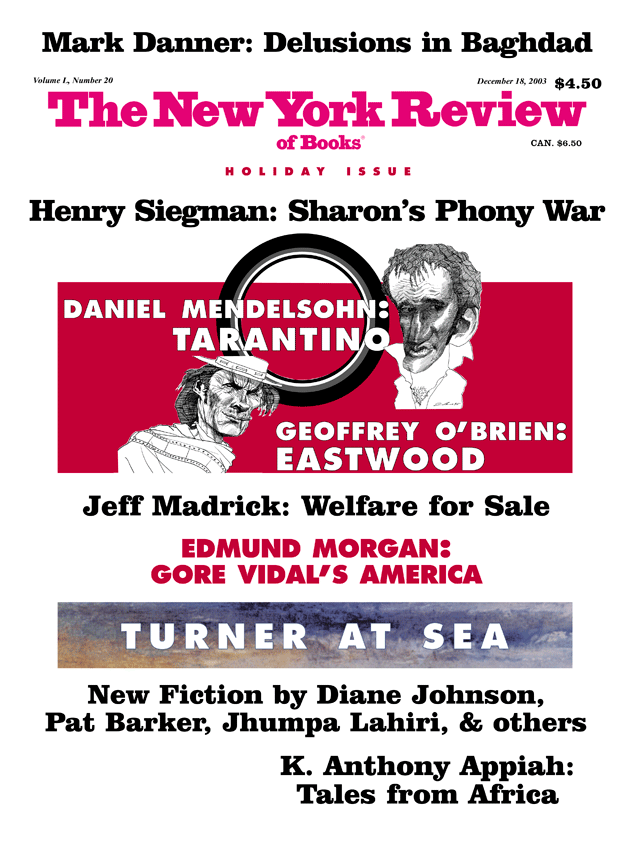

It is interesting that Eastwood, himself (in his early guises of Man With No Name and Dirty Harry) an icon of pop cinema, has so little in his filmmaking of pop gaudiness. His movies lack the retro-minded “movieishness” that pervades contemporary film culture; the aestheticized irony of Leone or Tarantino is not for him, nor do his action movies flaunt the self-conscious stylization of Jean-Pierre Melville or John Woo. When Eastwood’s movies are set in the past they make only the most perfunctory stabs at period feeling; there is no reveling in bric-a-brac for its own sake, and this paradoxically creates a sense of greater reality. White Hunter, Black Heart not only takes place in the 1950s but is about the making of a well-known movie and has a dramatis personae that includes thinly veiled versions of Katharine Hepburn, Humphrey Bogart, and Lauren Bacall, yet only a minimal effort is made at invoking the period, the look of The African Queen, or the mannerisms of the celebrities depicted.

This anti-nostalgic impulse can have startling results. In The Bridges of Madison County, the brief encounter of housewife Meryl Streep and roving photographer Eastwood is framed as a series of flashbacks interspersed between scenes that are supposed to be taking place years later, as Streep’s grown children read her diary of the affair and react more or less awkwardly to its implications. Rather than being consigned to a glowingly burnished past, the love affair has the disturbing effect of a permanently unresolved moment in a parallel present, incapable of settling into any more satisfying final image than a mother’s ashes being thrown off a bridge by her children in honor of her dead lover. The reading of the diary provokes a sense not of the bond between generations but of the unbridgeable gap between different realms of experience. The children will be forever shut out from the inner reality of their mother’s life; and the lovers themselves will fall back on their fundamental isolation from each other with an inevitability that no remembered song or belated token of feeling can assuage. The Bridges of Madison County can best be described as harshly romantic.

Movies, or at least the movies likely to be playing at the local multiplex, tend to offer themselves as a form of consolation, and it is disconcerting when that gesture is withheld. Even at his lightest—in, for instance, the adventure movie Space Cowboys (2000), in which three aging astronauts fulfill their failed youthful dream of space flight—Eastwood’s consolations tend toward the austere: the ostensibly heartwarming last image of Space Cowboys is of Tommy Lee Jones, who has sacrificed himself to avert a global catastrophe, lying dead on a lunar plain, while on the soundtrack Frank Sinatra sings “Fly Me to the Moon.” It certainly gives a fresh twist to the phrase “wanting the moon,” although the effect is nonetheless more sweet than bitter.

Nothing in Eastwood’s earlier work, however, quite prepares one for the unrelieved sadness of the world he evokes in Mystic River. Here he makes explicit a pessimistic realism that was previously only implied. Shot by shot he persuades us that nothing could have turned out differently, that notions like unlimited personal freedom and the capacity to triumph by sheer will over circumstance are—in the face of lingering trauma and intractable social codes—largely wishful thinking. We are far from the magical thinking that prevails in so many popular films, the assurance that a broken world can always be made whole, if not by a metaphysical force or a miraculous cure or a miraculous weapon, then by riding a wave of redemptive insight. There is indeed a flash of insight at the end of Mystic River—the formulation by Jimmy’s wife, played by Laura Linney, in a stunningly unexpected soliloquy, of a power-based morality that can justify her husband’s execution of Dave—but it isn’t the kind that redeems. Eastwood leaves us where we came in, in a fallen world more to be endured than overcome.

This Issue

December 18, 2003

-

*

Nominally directed by Richard Tuggle, Tightrope was according to some accounts made under Eastwood’s close directorial guidance. ↩