Late in the year 1818, the people of Constantinople witnessed the execution of a bandit chief who had been captured in the arid badlands of Arabia. Tried and convicted by the Ottoman Empire’s highest sharia court for heresy as well as brigandage, the rebel was dragged to the gate of the sultan’s palace. The decapitation itself was swift, but his severed head was then placed in a giant mortar and ceremoniously pounded into pulp; his body spiked on a tall pole and displayed, a sunken dagger pinning the sentence of irtidad—excommunication—to his bloodied chest for all to see.

The unfortunate Arab chieftain happens to have been an Al Saud,1 a direct forebear of the present-day rulers of Saudi Arabia, the place that is perhaps most readily associated with the practice of beheading in the modern world (at least, until terrorist snatch teams elsewhere began recording their sordid parody of divine justice on grainy video). In fact, the condemned man was Abdallah ibn Saud ibn Abdul Aziz ibn Muhammad ibn Saud, the reigning Saudi emir of the time and a great-grandson of the founder of the first Saudi state.2

The Al Sauds had been petty chiefs of a particularly poor, remote patch of central Arabia near the modern city of Riyadh when, sometime in the 1740s, the chance came of allying themselves with a revivalist preacher named Muhammad ibn Abdul Wahhab. The fusion of Saudi sword and Wahhabist fervor, still commemorated in the modern kingdom’s flag, elevated the Al Sauds’ ambitions from mere tribal raids into a full-scale jihad. Within two generations they had succeeded in conquering most of the Arabian peninsula, uniting the territory for the first time since the initial expansion of Islam a thousand years earlier.

But the early Saudis pushed things too far. In 1801 they sacked the Shia holy city of Karbala in Iraq, destroying its gold-domed shrines, slaughtering thousands of its inhabitants, and carrying off wives, daughters, and possessions. Such booty was theirs by assumed right, since the Wahhabists’ ultra-Sunnism taught that the Shia could not claim to be fellow Muslims. Their veneration of tombs was held to be a form of idolatry, a sin punishable by death. So when, in 1806, the Saudis overran the Ottoman garrisons of Mecca and Medina, cities holy to Sunnis and Shias alike, they again smashed every tomb they could find, forcibly applied their strict rules, and whipped, robbed, or murdered pilgrims who disobeyed.

At last, in 1811, the Ottoman sultan responded, delegating the powerful Wali of Egypt, Muhammad Ali Pasha, to dispose of this nuisance.3 His well-equipped army quickly recaptured the Hijaz, the region of the holy cities. But the campaign into the barren heart of Arabia was grueling. Fierce Saudi resistance led the invaders to adopt scorched-earth tactics. By the time the emir Abdallah surrendered, half the villages of central Arabia had been burned to the ground, their wells poisoned, their palms uprooted, their herds scattered. Some four hundred other Al Sauds were shipped to Cairo as hostages, a mercy considering that the Egyptians strapped many lesser sheikhs and Wahhabist clerics to the mouths of cannons and blew them to bits. The Egyptian commander was said to have forced the most revered scholar among the descendants of Muhammad ibn Abdul Wahhab to listen for some time to tunes played on a two-stringed fiddle (music being prohibited by the Wahhabists), and then had him shot.

1.

Judging by the tenor of much that has been said about Saudi Arabia since September 11, quite a few people seem to think something similar should be done with the present-day Saudis. In Congress, on American television, and in print, their country has been portrayed as a sort of oily heart of darkness, the wellspring of a bleak, hostile value system that is the very antithesis of our own. America’s seventy-year alliance with the kingdom has been reappraised as a ghastly mistake, a selling of the soul, a gas-addicted dalliance with death.

To Dore Gold, Israel’s former representative to the United Nations, Saudi Arabia is “Hatred’s Kingdom,” the prime source of the money and madness that fuel Islamist terrorism across the globe. Robert Baer, an ex-CIA agent who presents himself as a dashing foe of the jihadist international, saves his vehemence for prescriptions rather than description. The Al Sauds, he appears to suggest, should copy Syria’s brutish model, and exterminate their own extremists with

a huge armed force,4 or else face an American takeover of their oil fields, a partition of the kingdom, and the establishment of a puppet Shia state in its oil-rich Eastern Province, where the minority sect predominates. The journalist Craig Unger prefers to score partisan points closer to home. He suggests that the “secret relationship” between the Bush and Saud dynasties “helped to trigger the Age of Terror,” which is what we apparently now live in. His conclusion: the Bushes have saddled America to “a foreign power that harbors and supports our mortal enemies.”

Advertisement

Not all the recent literature on the kingdom is so categorically alarmist. Colin Wells’s concise, informative, and intelligent Complete Idiot’s Guide to Understanding Saudi Arabia is an excellent starting point for those who know little about the kingdom. Thomas Lippman of The Washington Post, a shrewd longtime observer and frequent visitor, has written a much-needed history of US–Saudi relations that is objective, sympathetic to both sides, and packed with anecdote. Although now somewhat dated, Mamoun Fandy’s Saudi Arabia and the Politics of Dissent offers a perceptive analysis of the different strands of Saudi-brand Islamism. The Brussels-based International Crisis Group’s recent report, “Can Saudi Arabia Reform Itself?,” provides a sober and authoritative take on Saudi Arabia’s current state and prospects.5

Despite its jarring title, Dore Gold’s Hatred’s Kingdom is well researched, particularly regarding the roots and pervasiveness of Wahhabi-inspired intolerance. The weakness is that whereas Gold, familiar from television as a spokesman for Israeli policy, gleefully highlights such things as Saudi anti-Semitism and xenophobia, he obscures the important part of Israeli and American behavior in fueling them. The passion for Palestine among Saudis and the wider Arab and Muslim world may be overhyped and at times self-serving, but it is nonetheless real.6 (Gold is also disingenuous in dismissing Saudi peace overtures to Israel as insincere. The Al Sauds risked considerable prestige to rally other Arabs to the peace plan they put forward in the spring of 2002, only to have it sunk by the stony silence from Jerusalem.)

Robert Baer also tends to the view that if the Saudis “hate us,” it is solely because of who they are rather than what we do. Yet amid much posing and innuendo, and despite the occasional howler,7 his book contains some sharp insights, as well as diverting gossip from the cafeterias of Langley. He reveals, for example, the commanding, behind-the-scenes influence of the wife of King Fahd, Jawhara al-Ibrahim, since the King was incapacitated by a stroke in 1995. Her control of access to the now-eighty-three-year-old invalid has apparently helped the al-Ibrahim clan to vastly increase its fortune. Such tales are common knowledge among Saudis, of course, but it helps to be reminded that Saudi women are not bereft of resources.

2.

As the Ottoman example shows, Saudi-bashing far predates the revelation that three quarters of the September 11 hijackers, as well as their boss, were Saudi nationals. Even if Americans once entertained National Geographic– tinted notions of noble Bedouin trading camels for Camaros, it is thirty years since those gave way—as soon as gasoline prices topped $1.00 a gallon during the 1973 oil shock—to the image of rapacious Ali Babas holding the West for ransom. Nor is it just in the West that the Saudis are unpopular. Urbane fellow Arabs have long pilloried their desert cousins as a Tartuffishly hypocritical cross between Beverly Hillbillies and witch-burning Puritans. To the millions of Asian menial workers who have endured indentured labor in the kingdom’s kitchens and on its building sites, the Saudi experience is recalled as something akin to the Hebrews’ suffering in Egypt, a mix of fleshpots, capriciousness, and cruelty. And of course Saudi Arabia’s uniquely stifling official version of Islam, with its head-chopping, its demonization of other faiths, and its binding and shackling of women under veils and petty legal strictures, is regarded as odious by just about everyone, including a sizable portion of Muslims.

In short, the Saudis present an especially plump, slow-moving target. Worse for them, being rich has not helped much. The importance of Saudi Arabia as a source of oil, as a market for costly goods, and as a strategic bit of real estate has certainly exerted a muting effect on the foreign governments that compete for its favors. Yet for Western public opinion, the Saudis’ fabled wealth has simply tended to tar the kingdom’s rare defenders as mercenaries, takers of blood money, and so on.

As with salacious tales of Saudi wickedness, the influence of Saudi millions tends to be blown out of proportion. The kingdom does, for example, spend a great deal of money to have its image improved: $17.6 million on lobbyists in the US alone since September 11, according to the Justice Department. But then, savvy foreigners often find it worthwhile to play American politics the American way. Diminutive Latvia, for example, recently hired a Washington firm to promote its bid to host the 2006 NATO summit. Besides, recent Saudi spending, nearly all of which went for advertising spots, is a relatively small contribution to the lobbying trough. If we leave aside Washington, we find that local American lobbyists booked some $890 million worth of trade in 2003 alone to influence state governments.

Advertisement

And while it is true that Saudi money secures wider influence through carefully placed procurement contracts and investments, the numbers hurled accusingly at them often fail to tally. Craig Unger, for example, makes much of the fact that the Saudis have passed close to $1.5 billion to what he describes as “individuals and entities closely tied to the House of Bush.” A closer look reveals that fully 85 percent of this was for defense contracts paid to firms owned by the Carlyle Group, a holding company whose fat payroll of Republican ex-officials renders it, to Unger at least, a card-carrying Bush operation.

Unger neglects to indicate that the Saudis patronized these firms long before Carlyle bought them, and have continued to do so since it sold them in 1998. The biggest big-ticket item during the 1990s, a $1 billion contract with the briefly Carlyle-owned Vinnell Corporation, simply extended the same company’s uninterrupted sequence of deals for training the Saudi National Guard dating back to 1975. Quite separately, Dick Cheney’s Halliburton did indeed rake in another $180 million of Saudi cash. But when we consider that Halliburton is the world’s leading oil-field services company, this was hardly a suspicious outlay for the world’s largest oil producer. This leaves a trickle of much smaller sums, such as the $1 million Saudi donation to the George H.W. Bush presidential library. As Unger himself admits, however, the Saudis have contributed to every single US presidential library built in the past thirty years.

Even more misleading are the much-bandied figures that ascribe unbounded boardroom clout to the kingdom. Unger says the country holds $860 billion in US stocks. Robert Baer confidently puts the hoard at $1 trillion, in addition to another trillion deposited in US banks.

To begin with, the Saudis are not dumb enough to leave a trillion dollars sitting in bank vaults. Secondly, the most that Saudi Arabia has ever earned from oil sales in a single year is $101 billion (in 1981, when the price of oil was at an all-time peak—and even that sum scarcely exceeded what Americans spent on cigarettes). To reach the trillion mark, the Saudis would have needed to save every single penny they earned. Yet the Saudi government has only balanced its budget twice in the past two decades, let alone achieved huge surpluses. The entire accumulated overseas holdings, private and public, of all Arab oil producers put together are unlikely to top $1.5 trillion, with much of this invested in such things as European real estate. That is about three years’ worth of American defense spending.

Gold, Unger, and Baer all cite the figure of $100 billion in Saudi weapons purchases from America since the 1970s as evidence that Washington has been duped into arming a potential enemy. But as Lippman points out, only a fifth of this outlay bought “lethal equipment.” The rest went for training, spare parts, and military infrastructure that has proved extremely useful to America’s own forces on several occasions. Shady as many of these deals surely were, the goal of defending the world’s main energy store is hardly unreasonable.

Unger is a fine writer, and he is right that the Bush dynasty has forged suspiciously cozy ties with the oil industry in general, and with several Arab oil monarchies in particular. He is fully justified in demanding to know things such as who authorized the hurried repatriation of rich Saudis in the immediate aftermath of September 11, and why. He would have been equally justified in raising other questions, such as what on earth Saudi officials were up to when they helped fund the San Diego sojourn of two of the future hijackers, and why the Bush administration has tried to conceal this episode.8 Yet with so much smoke in the air, and despite alarming signs of bungling, duplicity, or worse in Washington, one thing that Unger and others have failed to prove convincingly is that Saudi money has somehow swayed Bush policies to a further extent than it ever did those of other administrations, and thereby endangered American interests.

The stridency of the hyperbole suggests there are factors involved that have little to do with the Saudis’ general unlovableness. One of these is ignorance. Several of the authors mentioned above have never been to the kingdom. Few of their books provide sufficient background to explain what historical imperatives lay behind America’s pursuit of close ties with the Al Sauds (very rewarding for both parties, overall), or behind the later growth of anti-American sentiment within the kingdom (the fault of both parties, surely), or behind the Al Sauds’ lavish sponsorship of Wahhabist Islam (a far less successful venture, to say the least). Instead, these developments are portrayed as examples of perfidy and betrayal.

A corollary factor that leads to exaggeration of the purported Saudi menace is fear. The kingdom, we are constantly reminded, sits on a quarter of the world’s oil reserves. In 1970, the United States became a net importer of the stuff that fuels its livelihood. It crossed another threshold of dependence in 2000, when imports accounted for more than half of consumption for the first time. The trend is clear. Global demand continues to surge, most dramatically of late in China (which plans to finish a highway system more extensive than the US interstate network by 2015). With the easily extractable reserves that lie outside the Persian Gulf set to be exhausted within decades, the kingdom’s gushing hundred-year stash will only grow in importance.

Worse, say the pundits, the Al Sauds’ corrupt, feudal rule is doomed. So fragile is it that we are in danger of “our” oil being hijacked, either by fanatics or by fearful princes willing to appease them. The country, warns Robert Baer, is a powder keg. A coordinated terrorist attack on the kingdom’s pumping and shipping centers, he reckons, would quadruple oil prices overnight, triggering global economic collapse and “a level of personal despair not seen since the Great Depression.”

It is never wise to ignore worst cases. But as the Saudi minister of petroleum, Ali Naimi, is fond of saying, oil is a fungible commodity. If you fail to get it from one place you can always get it from another. This means that whoever rules the kingdom would be wise to avoid raising the price of oil too high. When the Saudis did that in the 1970s, they made it worthwhile for oil importers to curb consumption drastically, and for oil companies to go after the far more expensive-to-produce reserves of such places as the North Sea and Alaska’s North Slope. As the Saudis are well aware, the result was that the country has yet to regain the global market share it enjoyed thirty years ago.

A sudden rise in oil prices now would certainly cause shocks, but it would also make economically feasible the exploitation of, say, Canada’s vast and conveniently located reserves of oil shale. Americans might actually fall out of love with their thirsty SUVs, and might even condone the higher taxes on gas that already force Europeans and Japanese to use the stuff sparingly.

It is a historical fact, moreover, that Saudi Arabia has habitually wielded its power on world oil markets to serve American interests. An obvious exception was during the OPEC boycott provoked by America’s perceived tilt toward Israel during the October 1973 war. But then the kingdom was just one of the thirteen oil exporters that briefly suspended oil sales, and this rift in the Saudi–American alliance healed quickly. During the Reagan administration, Saudi Arabia effectively became a weapon in the all-out assault on communism. It was not just the Afghan Mujahideen who benefited, fatefully as we well know, from Saudi largesse, but America’s proxy fighters on other cold-war fronts, from Angola to Central America to the Horn of Africa. Less dramatically but perhaps more crucially, the kingdom also bled the Soviet Union by keeping oil prices down throughout the 1980s, just when the Russians were desperate to sell energy in order to keep up with huge hikes in American military spending. In periods of shortage during the past ten years, such as during the Iraq wars and Venezuela’s 2002 oil strike, the Saudis have cranked up production to keep prices stable.

In any case, no matter who rules it, Saudi Arabia will still need to pump lots of oil. Its people are just as dependent on the rest of the world as it is on them—perhaps even more so. Without air conditioners and desalination plants, the kingdom would quickly look like Darfur. Not even religious fanatics are ready to go back to the sweaty business of raising goats and dates.

3.

None of this, however, means that either the Saudis or the rest of the world should be complacent. The signs of something gone very wrong are manifold, from the Saudi part in exporting jihadism, to the recent spate of gory terror attacks within the kingdom, to its rapidly rising rates of poverty and joblessness, to simple impressions such as the mute grimness of passengers—returning citizens and expatriates alike—filing like convicts toward passport control at Riyadh’s grandiose but dimly lit airport.

Talk to politically engaged Saudis and they freely describe their condition as a malaise, a disease. Where they differ is in identifying symptoms and prescribing cures. Conservatives see a concerted secular assault on their cherished Islamic immune system; liberals see the spread of religious obscurantism as a creeping blindness, or, in the words of one of the senior princes, as a “cancer” that must be excised.

But most Saudis do not fit neatly into liberal or conservative molds. Their strong faith is a matter of pride and instinct more than of political persuasion. A government-sponsored poll carried out last year found that a huge majority of Saudis see unemployment as the country’s main problem, not religious extremism. It also revealed that while half of Saudis respect Osama bin Laden’s political message, only one in twenty respects his political leadership. Their very real chauvinism does not necessarily close them to the modern world, its challenges and its delights. Even outside the worldly elites of Jedda and Riyadh, Saudis are as likely to spend time watching soccer games on television or reading fashion magazines as going to the mosque.

The mosque does remain inescapable, however. Almost half of Saudi state television’s airtime is devoted to religious issues, as is about half the material taught in state schools.9 Nine out of ten titles published in the kingdom are on religious subjects, and most of the doctorates its universities awards are in Islamic studies. Yet even without such Wahhabist saturation, Saudis would be keenly aware that their heritage imposes distinct responsibilities. This is, after all, the birthplace of Muhammad and of the Arabic language, the locus of Muslim holy cities, the root of tribal Arab trees, and also, historically, a last redoubt against foreign incursions into Arab and Muslim lands. The kingdom is in many ways a unique experiment. It is the only modern Muslim state to have been created by jihad,10 the only one to claim the Koran as its constitution, and one of just four Muslim countries to have escaped European imperialism. Of the others, Iran is Shia, Turkey opted by itself for secularism, and Afghanistan is a wreck.

Where present-day fanaticism creeps in is when this uniqueness is felt to be under threat; when it is sensed that the Saudi dream of an Islamic utopia is fading. What unites the kingdom’s conservatives—and they come in many stripes, from suicidal jihadists who seek to recreate a global Islamic caliphate, to pacifist puritans, to the loyalist Wahhabi scholars who pack the judiciary and the education system—is a determination to sustain this dream. And despite the unpleasantly coercive nature of Islamic practice in the kingdom (few among the world’s other 1.2 billion Muslims think that forbidding women from driving is anything but absurd), a surprising number of ordinary Saudis, including women, endure the annoyance because they happen to share the dream.

Most Saudis also continue to support their ruling family, albeit no longer with much enthusiasm. Its leading members, including the King, the crown prince, and the second, third, and fourth brothers in the line of succession, are uniformly old and out of touch. The sheer number of lesser princes—something like seven thousand—combined with their sense of entitlement to feudalistic spoils, whether these be key government jobs, business concessions, or prime property, has alienated ordinary citizens who have come to expect a fairer share of the country’s natural wealth. Princely households, with their wide circles of retainers and favorites, marriage alliances and business partnerships, are no longer seen by commoners as potential vehicles for upward mobility, but as obstacles. To disillusioned religious zealots, the Al Sauds are simply “hypocrites,” a scripturally loaded Islamic term meaning those who feign piety while serving enemies of the faith.

Yet many Saudis also accept the need for the Al Sauds to perform their traditional role as consensus-makers between the interests of tribes, regions, urban classes, foreign powers, and shades of religious feeling. The family’s critics often fail to appreciate the importance of this balancing function in having helped to secure, peacefully for the most part, one of the most rapid and stark transformations that any society has ever experienced.11 The increasing polarization of Saudi society in recent years, between those demanding progressive reform and those insisting on retrenchment within a religious cocoon, may even have reinforced the Saudis’ reliance on the ruling family. Until such time as a new constitutional order can be built, it is the kingdom’s only bridging institution.

If their subjects find it hard to imagine the country surviving without the Al Sauds, there is nevertheless a widespread sense of confusion and anxiety for the future. By turning into a substitute for leadership, the Al Sauds’ balancing act has itself become a source of insecurity. “Balancing” the arrest of violence-inciting preachers with the arrest of petitioners for constitutional reform, as has happened in recent months, gives an impression of rigidity and drift rather than wisdom and firmness. Some have concluded that such policy contradictions reflect not judicious equivocation but ominous ideological splits between royal factions.12

Whatever the cause, there is little doubt that a lack of determined leadership has worsened the kingdom’s troubles. Faced in the late Seventies with the challenge of rising religious radicalism, the Al Sauds opted for appeasement. Conservative control of schools and courts was strengthened. Even as thousands of Saudis furthered their education in Saudi-endowed American colleges, thousands more went to Saudi-funded training camps in the hills of Afghanistan. Stung again in the 1990s by local anger against King Fahd’s invitation for America to strike Iraq from “holy” Saudi soil, the Al Sauds again appeased critics by finding offshore outlets for home-grown radicalism in such places as Chechnya and Bosnia. The contradictions came to a tragic head when Osama bin Laden, from one of the richest nonroyal Saudi families, hero of the Afghan war, broke with his former royal patrons and turned his guns on their old ally, America.

Obviously, it has taken far too long for the significance of this development to dawn on the Al Sauds. Terrorist bombings in the kingdom in 1995 that killed twenty-four Americans, and a series of smaller attacks on individual expats over subsequent years, were all dismissed as the work of foreign agents or criminal gangs. A year after Sep-tember 11, Prince Nayef, the minister of interior, was still denying that Saudis were involved. A year after that, he denied that al-Qaeda had any significant presence in the kingdom. The opacity of Saudi rule made it easy for critics to ascribe such shilly-shallying to a desire to conceal high-level complicity in such affairs, but the truth is likely to be more mundane. In typically obtuse patriarchal fashion, the Al Sauds were seeking to settle their problems the usual way, “within the Saudi family.”

Their failure to do so is now all too evident. Aside from the havoc it has wreaked elsewhere, al-Qaeda violence inside the kingdom has cost nearly a hundred lives during the past year. Thousands of Saudi youths, many of them jobless and bored, remain fired by the romance of jihad. Iraq, with its Spanish civil war–style Islamist international brigades, has become a destination for some. More remain at home, dreaming of a chance to stone the imagined devils of royal hypocrisy and infidel aggression.

Containing and redirecting such passions would take patience, determination, and huge resources. There is good reason to doubt that the Al Sauds, at least under their current muddled leadership, can muster and sustain all three. But they are, at long last, beginning to try. New controls have drastically curbed private financial support for jihadist groups. Hundreds of extremist preachers have been banned from mosque pulpits. Dozens of the most radical are behind bars. The official clergy now sermonize ad nauseam about the danger of “exaggeration” in religion, and much of the religious incitement in Saudi textbooks has been purged.13 As for security, the Saudis have greatly improved their border controls and arrested hundreds of al-Qaeda suspects. Perhaps most importantly, the indiscriminate bloodiness of local terrorists has seriously alarmed the general public. Their political vision has been revealed as grossly unappealing.

The rest of the world tends to share the impatience of Saudi liberals who would like to see stronger action, as well as faster and deeper reforms. The Al Sauds’ preference for consensus will, however, probably keep the pace slow. This augurs more frustration. Women, obviously, have a strong stake in being released from the stifling “protection” of laws that relegate so many to lives of boredom, dependence, and isolation. Stagnation is also dangerously irksome to the already restive young who make up such a large proportion of the population. In view of their impractical education, the scarcity of jobs, and the increasingly prohibitive cost of marriage, the millions of Saudis who are coming of age face a difficult future.

“I feel sorry for my students,” says a professor at Imam Saud University in Riyadh, a place that has graduated a disproportionate number of al-Qaeda recruits. “They don’t know who to believe. They have no role models.”

Like many other Saudis, the professor thinks it is far too early to hope for democratization. The best short-term solution would be a strong, single-minded king. Only such a figure, he says, would be able both to rein in “wild” princes and to push through sweeping social, economic, and political reforms. His longer-term fix is more controversial. “There is no longer a shared language between royals who understand the world and are sophisticated, and religious scholars who are backward. Conflict is inevitable. What we need is to reduce the connection between religion and state.”

More and more Saudis seem to be coming to this conclusion, though it will probably take decades before there are enough of them to make a difference. But if the link to Wahhabism is severed, what will be Saudi about Arabia?

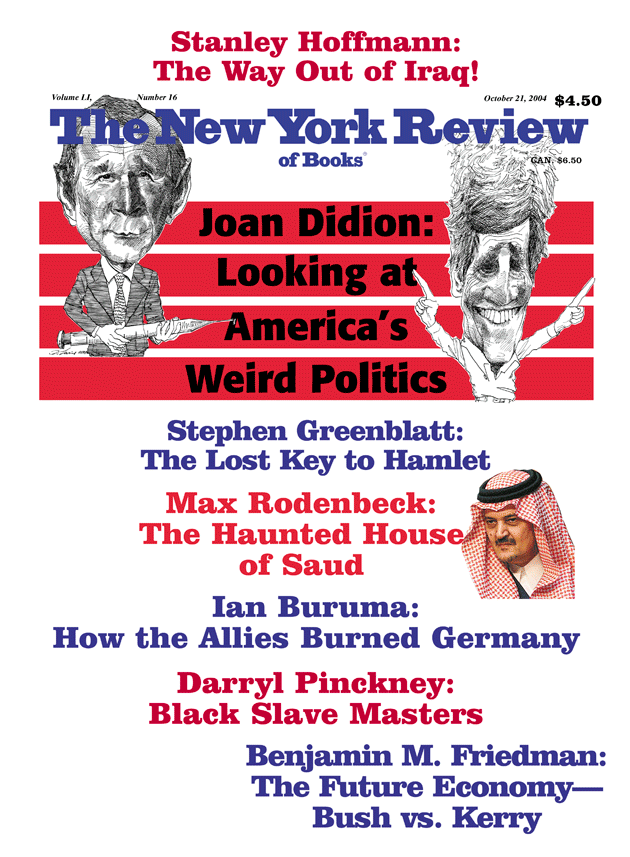

This Issue

October 21, 2004

-

1

The “Al” here, pronounced with a long “a” as in Al Sharpton, refers to the extended Saud “family,” as opposed to the short “a” of the Arabic article al-, as subsumed into such anglicized Arabic words as algorithm and algebra. ↩

-

2

There have been three Saudi states, from 1744 to 1818 (destroyed by the Egyptian army), from 1843 to 1891 (weakened by succession struggles and overthrown by the rival Al Rashid clan), and from 1902 to the present. The title of “kingdom” dates only from 1932. ↩

-

3

The Ottoman Turks had ruled most of the Arab east, including Mecca and Medina, since 1517, when they defeated Egypt’s Mamluk Sultanate. Practical administration of the holy cities was largely left to their governors in Egypt, a country whose rulers had held this privilege since the tenth century. Inner Arabia was of so little value that the Ottomans, like most Muslim empires before them, had never bothered to subdue it. ↩

-

4

The example he refers to is the Syrian army’s shelling in 1982 of the old city of Hama, at the time a haven for the Muslim Brotherhood and other Islamist groups. As many as 20,000 Syrians are said to have died. ↩

-

5

Released July 14, 2004, at www.icg.org. See also a subsequent International Crisis Group report, “Saudi Arabia: Who Are the Islamists,” released September 21, 2004. ↩

-

6

Gold ought to know that terrorism can be fought most effectively by recognizing that the line separating one person’s idea of inexplicable barbarism from another’s notion of legitimate resistance can sometimes be very fine. Al-Qaeda and the Palestinian group Hamas may look the same to Israelis, but their goals and constituencies only partly overlap. The very Saudis signing checks to fund what they see, rightly or wrongly, as the Palestinians’ liberation war against Israeli occupation may at the same time be disgusted and perplexed by al-Qaeda’s claim that bombing commuters in Madrid counts as “resisting” what it sees as America’s global crusade against Islam. ↩

-

7

The Muslim Brotherhood was not responsible for the 1997 massacre of tourists at Luxor, nor is it correct to call its adherents “mass murderers,” or “the most adept terrorists of them all.” The organization, founded in 1928, is indeed an ideological forebear of more extreme groups, but it renounced violence years before the emergence of jihadist militancy in the late 1970s. ↩

-

8

This fact, first uncovered by the joint House-Senate intelligence committee’s September 11 investigation, but later deemed classified by the administration, is at the heart of concerns about Saudi Arabia voiced by Bob Graham, the retiring Senate committee chair, in his new book Intelligence Matters (Random House, 2004). Graham reveals that a suspected Saudi agent “helped” the two Saudi immigrants to settle into San Diego with gifts that may have amounted to $40,000. Just as disturbingly, he shows that one of the two happened to share accommodation with a paid informant for the FBI, who apparently never noticed anything suspicious. (The FBI refused point-blank to let the legislators question their informant.) ↩

-

9

By the estimate of an elementary schoolteacher in Riyadh, Islamic studies make up 30 percent of the actual curriculum. But another 20 percent creeps into textbooks on history, science, Arabic, and so forth. In contrast, by one unofficial count the entire syllabus for twelve years of Saudi schooling contains a total of just thirty-eight pages covering the history, literature, and cultures of the non-Muslim world. ↩

-

10

Abdul Aziz ibn Saud, father of the current king, conquered the territory between 1902 and 1926, largely by the use of fanatical Wahhabist warriors known as the Ikhwan. The historian R. Bayly Winder comments: “The numerous and striking similarities between Wahhabism and Islam itself, including such points as original locale, doctrinal emphasis, pattern of military success, Arabness, iconoclasm, and Puritanism, are so marked that one is inclined to view Wahhabism as a kind of ‘second coming’ to Arabia.” See Saudi Arabia in the Nineteenth Century (St. Martin’s, 1965). ↩

-

11

Not only extensive urbanization and a huge rise in living standards, but also the overcoming of fierce religious resistance to such innovations as pa-per money (1951), abolishing slavery (1962), female education (1964), and television (1965). ↩

-

12

See Michael Scott Doran, “The Saudi Paradox,” Foreign Affairs, January– February 2004. ↩

-

13

Changing books is just a start. One Riyadh schoolteacher describes being disciplined by his principal after an eight-year-old student fingered him for telling his class that music is not necessarily sinful. By contrast, a teacher in the same school received a commendation for ordering his students to amend newly distributed government textbooks, altering a passage that described a young girl and boy as being “friends” so as to make both characters male. Even in a children’s schoolbook, apparently, “mixing” among the sexes remains taboo. ↩