It’s hard not to think of Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel The Remains of the Day when reading Mark Danner on what will forever be known as the Downing Street memo. Ishiguro told the story of a butler, just beyond the periphery of tawdry events in high places in World War II England, who pieces together fragment by fragment the story of his lord’s collaboration with the Germans. So Danner, standing at a remove from momentous sotto voce conversations among the British ruling class on the eve of another war, teases out the meaning of similar evidence at his disposal until finally we get a clear and damning larger picture of a plot to take both England and the United States into a war of choice in Iraq on false premises. But you can only take this analogy so far. Unlike Ishiguro’s tragically limited narrator, Danner understands the implications of every piece of the story, and, in these pages,* lays out the history of “the secret way to war” with devastating acuity.

The Downing Street memo, first published by The Sunday Times of London on May 1, 2005, contains the secret minutes of a meeting Prime Minister Tony Blair held with his government’s national security and foreign policy hierarchy in July 2002. “C,” the head of British intelligence, reports on his findings from a recent visit with the equivalent players in Washington. Despite public claims that it would go to war in Iraq only as “a last resort,” the Bush administration had months earlier decided to wage that war no matter what, “C” says. All that was missing was a way to sell it, and to do so, Washington was now engaged in a campaign to see to it that “the intelligence and facts” would be “fixed around the policy.” That intelligence and those facts, of course, all pertained to Saddam Hussein’s weapons of mass destruction, the war’s ostensible casus belli, which we now know did not exist.

Out of this memo—indeed out of that one phrase in the memo—nearly everything else in the sordid story of the way to war flows: the refusal to allow the United Nations weapons inspectors to finish their work in Iraq, as Hans Blix and every American ally except England wanted; the activities of the so-called White House Iraq Group to publicize cherry-picked (and erroneous) intelligence produced outside the normal channels by what Lawrence Wilkerson, Colin Powell’s former chief of staff, has called the Dick Cheney– Donald Rumsfeld cabal; the egregious “intelligence and facts” about weapons of mass destruction presented to the UN Security Council and the world by Powell; the parade of what Danner calls “increasingly lurid disclosures” by the Bush administration to the press about Saddam’s doomsday weapons in the run-up to war; and the Valerie Plame Wilson leak case, which has revealed just how eager the White House was to punish anyone who might expose the extent to which the intelligence and facts had indeed been fixed on WMDs.

In retrospect, much of this subterfuge was hiding in plain sight. Yet the American press, much of which had been overly credulous in reporting the “evidence” of Saddam’s weapons program to start with, was not particularly eager to correct the record when the fictions were exposed after the invasion. Like the public, which soured on the war in the invasion’s aftermath, much of the American news media was eager to turn the page. When the Downing Street memo first surfaced in the British press, no major mass American journalistic outlet rushed to print the text in full or even to much deliberate about its contents. That job fell instead to The New York Review of Books. The detached and defensive view of even the sharpest of the so-called liberal American press can be seen most clearly in the extended exchange, included here, between Danner and Michael Kinsley, then the editorial page editor of the Los Angeles Times.

As Danner predicts, the number of Americans who believe that the President and his administration intentionally “misled the American public before the war” has steadily grown with each passing week since the revelation of the Downing Street memo. The press has since caught up with the public and is belatedly filling in every chapter in this duplicitous narrative that it can. But, as was also the case in his early commentaries for The New York Review on the documents delineating America’s road to the practice of torture in Abu Ghraib and beyond, Danner was among the first to separate the threads of reality from the Alice-in-Wonderland fantasies the American government and its well-oiled propaganda machinery would have us believe. No other writer has done it with remotely his precision and deadpan wit.

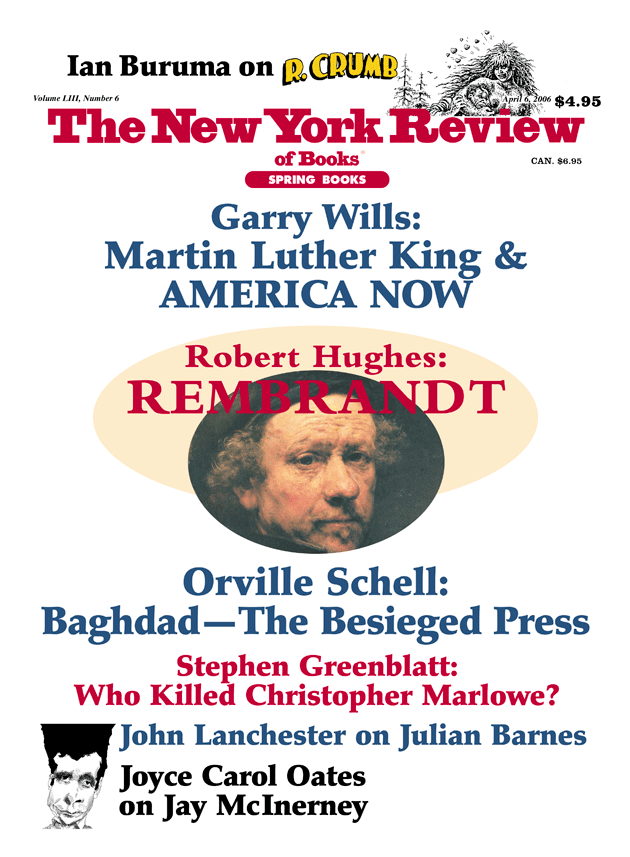

This Issue

April 6, 2006

-

*

This essay will appear as the preface to The Secret Way to War by Mark Danner, to be published by New York Review Books in April 2006. ↩