A society in which production is governed by blind economic forces is being replaced by one in which production is being carried on under the ultimate control of a handful of individuals. The economic power in the hands of the few persons who control a giant corporation is a tremendous force which can harm or benefit a multitude of individuals, shift the currents of trade, bring ruin to one community and prosperity to another. The organizations they control have passed beyond the realm of private enterprise—they have become more nearly social institutions.

It is thirty-one years since Adolf A. Berle and Gardiner C. Means published The Modern Corporation and Private Property (whence the quotation above), but three intervening decades have not outmoded this extraordinary book. To be sure, some of the names included on their famous list of the 200 largest non-banking corporations have been displaced by other names, and the economic power of the list itself has not grown quite so alarmingly as Berle and Means feared (in a moment of fantasy they suggested that by the year 2300 the 200 giants might be fused into one single immense corporate organism with a business life expectancy of over 1,000 years). But the issues posed by The Modern Corporation and Private Property are no less resonant and no less contemporary on that account. For as the title of the book made clear, this was not just an inquiry into economic performance. It was also, and perhaps more profoundly, an inquiry into economic philosophy. In a fundamental sense it questioned not only the practices of the great concentrate of economic power, but the very right of that concentrate to exist. Having revealed traditional economic theory to be little more than a pious theology, it asked what was left to describe the American economic system except a Realeconomiic of privilege for privilege’s sake?

For Gardiner Means, economist and statistician, the economic problems raised by the concentrate—market power, price-fixing, collusion and competition—marked out the road to be followed in later work. But for Berle, professor of law, diplomatist and amateur politician, it was the philosophic issue which was the more attractive. “It is conceivable—indeed it seems almost essential if the corporate system is to survive—“ he wrote at the conclusion of the book, “that the ‘control’ of the great corporations should develop into a purely neutral technocracy, balancing a variety of claims by various groups in the community and assigning to each a portion of the income stream on the basis of public policy rather than private cupidity.”

“Is this suggestion of a responsible business community merely a dream?” he asked elsewhere. Thirty years later, The American Economic Republic constitutes his answer.

It is not, unhappily, the best of his books. The 20th Century Capitalist Revolution (1953) is tighter and sharper; Power without Property anticipates what is to come later and is more interesting. By contrast with these, The American Economic Republic sprawls and repeats and vaporizes.* Nonetheless, it is a book worth careful consideration, for the problems it raises are of utmost importance.

The book begins where The Modern Corporation and Private Property ended: with the issue of property itself. Clearly, says Berle, the traditional conception of property as personal chattels—the property which Locke said belonged to a man because he had “mixed his labor” with it—has little relevance to the “property” of an industrial system. Property must now be seen as an aspect of power; it is not merely things, but organization, momentum, the capacity to command resources. This kind of property, which is the central reality of the economic process, is controlled by a small group of more or less self-perpetuating managers who are subject to various pressures which we shall consider in a moment.

But note that the rationale for the existence or use of these great blocks of power-property cannot be found under the traditional view of property as proprietorship. The managers do not “own” the power complexes they direct; the “owners” are holders of another kind of property—“passive property” which entitles them to an uncertain claim on the earnings of the great concentrate and to the chance to make money by dealing in their certificates of “ownership” shrewdly. This kind of property may be a great convenience, but it has virtually nothing to do with assuring the successful operation of the real power-property for which it is presumably a counterpart.

Thus the concepts of the 19th century dissolve under Berle’s acidulous intelligence, and along with them dissolves the comfortable justification for property as things made by and used by their owners. We are left with the much more pragmatic calculus of results rather than premises: property is legitimate, not in and of itself, but to the extent that it is used as society wishes and to the extent that it yields results of which society approves.

Advertisement

But let us not linger here. Having subjected the standard rationale of property to this disenchanted analysis, Berle now asks similarly disconcerting questions of two other hoary underpinnings of the traditional capitalist rationale. One of these is capital, which he has no trouble in dissociating from its beatified progenitor, the thrifty capitalist. Capital is not created by thrifty capitalists in the American economic republic—at least not in important measure. Capital is created by extracting it from the consumer, who is quite unaware when he buys a consumer durable good that part of his payment will end up as the corporate “saving” which is made out of profits. In like manner, the free market—that holy of ideological holies—is given short shrift. The market, Berle makes plain, is not a state of nature but a state-created, state-sustained institution, and beyond that, one which “has been completely displaced as an infallible god, has been substantially displaced as universal economic master, and increasingly ceases to be, or to be thought of, as the only acceptable way of economic life.”

Is there left, then, only a refined neo-feudalism—a naked system of power responsible only to itself? In an earlier book, The 20th Century Capitalist Revolution, Berle had indeed placed his corporate giants in a position of untrammeled power. “The only real control which guides and limits their economic and social action,” he wrote, “is the real, though undefined and tacit, philosophy of the men who compose them…. To anyone who studies and even remotely begins to apprehend the American corporate system, the implications of the line of thought here sketched have both splendor and terror. The argument compels the conclusion that the corporation, almost against its will, has been compelled to assume in appreciable part the role of conscience-carrier of twentieth century American society.”

The prospect was clearer in its terror than in its splendor, for it implied that the American system was to be ultimately responsible to men—hopefully, to enlightened men—over whom no political, and very little economic, control existed. But in the subsequent Power with Property Berle sought to amend this dictatorial interpretation of affairs. For the conscience of the corporation was, he claimed, not the product “of the centers of power and responsibility directing the economic machinery.” Rather it emanated from the universities, the press, the professions—the “spiritual elite.” In turn, this core of economic power had to be responsive to the democratic process itself. For the economic republic, Berle emphasized, was essentially a political entity. Its economic institutions, no matter how powerful, were always subservient to its political institutions; its economic powers, no matter how seemingly impregnable, were always subject to check—and in the long run, to control—by the democratic will.

Much of The American Economic Republic is taken up with a description of the various political agencies by which private power is curtailed, and to a description of the ways in which business, labor, government and public welfare sectors interact and counterbalance to bring about the “republic” itself. But this is not yet the capstone to the system. For behind the corporate conscience, behind the spiritual elite and the democratic process, Berle now discovers a final set of values which impels and sustains the American political economy. He calls it the Transcendental Margin, meaning by this the capacity of the system to create a surplus of creative energy, a drive over and above that adduced by mere selfish considerations. It is the presence of a transcendental margin which made Utah flourish while Nevada stagnated, which propelled Israel but not Iraq, the Netherlands but not Bulgaria.

“Let us not claim that the transcendental margin is peculiar to the American social-economic system….” concludes Berle. But in the United States the transcendental margin was continuously greater, and expanded more consistently, than in most other contemporary systems. It generated greater productivity, and greater intellectual resources for still further expansion. In the post World War II period, it has become the decisive influence.”

Therewith, in desperate condensation, is Adolf Berle’s answer to the question he posed thirty years ago: Is a responsible business community possible? His answer is clearly: Yes, it is; it exists here in America; it can be examined in the still unfinished American economic republic.

One characteristic immediately lifts this analysis far above the level of any other conservative appraisal of the system. It is Berle’s capacity to divorce his defense from the usual deceits and rationalizations. The massive concentration of private power, the indispensable role of the state, the make-believe of laissez-faire economics—these stumbling blocks for the ordinary conservative are no problem to Berle. On the contrary, he is one of the discoverers of the extent of corporate power and of the necessity of a mixed economy. Fortune magazine may rhapsodize over a new textbook by the very conservative Wilhelm Roepke; Berle cites Roepke’s name only to associate it with the do-nothing policies which plunged Germany into the depths of her 1931 misery. Thus when Berle deals with the institutions of the present system, with the sheer facts of power, the realities of the “market,” the interplay of public and private power, he is without peer, liberal or conservative.

Advertisement

Unfortunately, however, this is not where matters end. Berle is not content to demolish the shaky ideology of the past, to demonstrate that the system works according to different rules from those of the textbooks and that the existing system seems to respond to some kind of “social control,” albeit of a weaker kind than envisaged in classical economic thought. Instead he goes on to dress this essentially neutral judgment in an ideological garb of its own—not only to explain it but to justify it. And here, I fear, the sharp and particularistic and fearless intelligence of the analytic Berle gives way to a soft, uncritical and complaisant view.

I note, to begin, a tendency to use some “facts” in curious ways to make a point. Thus, speaking of stock ownership (pp. 53 and 54), “The wealth-distribution process…goes steadily and implacably forward….” Does it? Berle’s own source, the study by Robert J. Lampman on wealth ownership, shows an increasing concentration of share-ownership between 1922 and 1953; and recent income distribution studies have shown no perceptible improvement in income distribution (and some worsening) since the great World War II redistribution.

Or again, on page 183: “Current statistics indicate a total unemployment of slightly over 4,000,000…. Under the definitions of ‘unemployed’ applied to Western Europe the American unemployed would be counted more nearly at 2,500,000….” And later: “There are, at a sophisticated guess (no figures are available), about 4,000,000 in [Russian] concentration camps of forced residence now. These equate to the American figure of unemployed…. The communist system did not eliminate unemployment, but merely gave it another name.”

This is a misuse of figures to the point of irresponsibility. Given all statistical adjustments, U. S. unemployment rates are double to triple those of Europe—I take as my source the Presidential Address of Edward Mason to the American Economic Association this winter. And if there are “no figures,” how does Berle blandly assume that 4 million Russians are in concentration camps? I know of no authority from whom such an estimate could have been obtained. And even assuming that there were 4 million Russians in concentration camps, by what logic can these be equated with the victims of the economic malfunction of the American republic? Is Berle claiming that our economic casualties are matched by the victims of political malfunction in Russia? Then what of our own political victims: the Negroes condemned to half the average income of the whites, or the unemployed for whom we are unable to muster the votes which will bring economic relief?

This prettifying of the figures, this minimizing of evils, this false analogizing and easy glossing over of unpleasantness (“A tolerable, not to say comfortable, situation exists for nine-tenths of the population of the United States”) reveals an unwillingness to probe into matters of over-all performance as searchingly as into matters of legal definition. And this tendency to whitewash is made the more evident when we consider not only what is in the description of the economic republic but what is left out. Thus we find no mention of the misbehavior of important sections of the managerial elite, as for instance in the electrical conspiracy. No thoughtful analysis is made of the morality of Ralph Cordiner or the intelligence of Roger Blough. The level of comprehension or compassion to be intuited from the speeches of our business leaders, from the pieties and platitudes of the business press, from the editorials of our mass media, from the congressional testimony of our trade associations—none of this is weighed in the balance. Nor is there mention, in discussing the “successful” operation of our system, of its dependence on an armaments industry huge in size and not easy to excise or replace. Nor did I find in a description of the American economic republic any discussion of the extent to which the “consensus” which supports (and supposedly judges) the business manager is itself constantly pumped up by the deliberate efforts of the managers themselves.

And then, what are we to make of the transcendental margin—that driving force behind the American economy? I could imagine attributing this force to the thirst for profits, which, at least in the late 19th century, drove some men to prodigies of effort. But the drive after profits is specifically excluded by Berle from the ultimate propulsive values. What are they then?

Two values would emerge high on the list. One would be the value known in philosophical language as “truth.” By this I mean truth in the large, in all aspects, from individual interest in not telling lies and in personal sincerity, to the frontiers of scholarly search…. A second enduring value is beauty…. The constant conflict by the more honorable portion of the American community against sordid murder of the esthetics of an open road by advertisers, or to maintain the dignity of an honorable main street against dollarchasing real-estate schemes, testifies to that fact.

Are these the dynamic forces of our nation? As I wander about the American republic, watching the slums move out, not in, witnessing the exposure of my children to the “sincere,” “truth-telling” voices on the great silver screen, contemplating the dreary spectacle of payola and fix, delinquency and crime, racket and cynicism, of passivity before evil and acquiescence in ugliness, I must confess that I find it difficult to assert that Berle’s values are in control.

Not that these values do not exist. I think the problem is that there is not one American Economic Republic but two. One is inhabited by those on whom fortune has smiled. It begins at the Pan Am building and ends on Park Avenue and 96th Street. It is the view from the top, the view in which things work, in which flaws seem small and relatively unimportant, in which reasonable men, lunching comfortably, can come to reasonable agreement about how to decide reasonable things, in which the impotence of the unlettered, the unimportant, the unskilled is never experienced at first hand, in which—with full recognition of the exceptions which must, of course, be borne in mind—all’s right with the world. But there is also another republic, which begins at 96th Street and continues north into the wynds of Harlem and the dreariness of the Bronx and Yonkers, and from this republic there is another view, more constricted, less Olympian, meaner, poorer, unhappier. We fortunate citizens may never have to visit, much less live in, the commonwealth of the less fortunate, but a book which aims to describe and to judge the American economic republic as a whole must give just as much weight to each miserable and unprivileged citizen as to each contented and favored one, if it is to be, in fact, a description of the way things are, and not merely the way we hope they are.

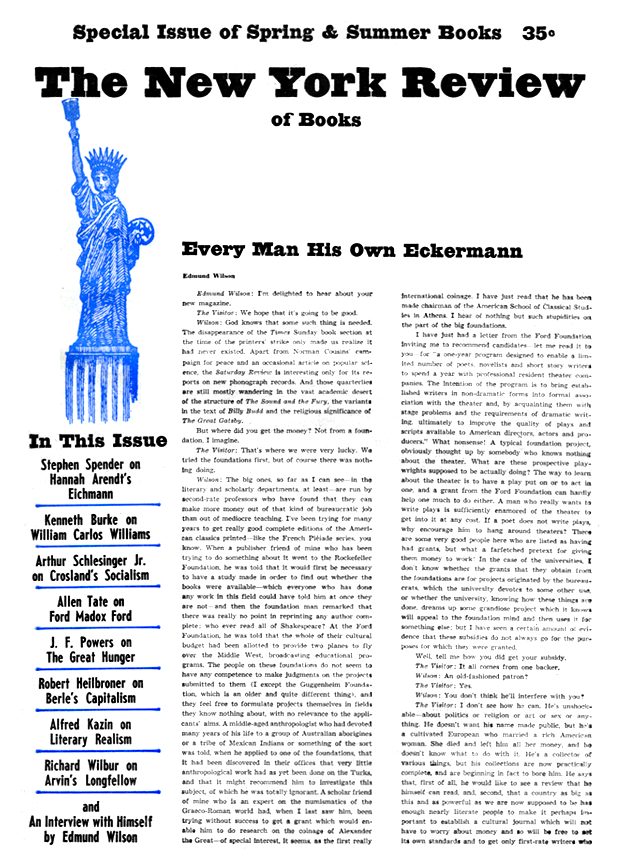

This Issue

June 1, 1963

-

*

I must add an ill-tempered footnote about the abominable editing this book has received. Even a cursory editing should have eliminated the repetitions in both text and footnotes, and should have seen to it that the footnotes were tied to the appropriate sections of the text (e.g., note 23 belongs on p. 122, not on p. 118). The jacket blurb is simply embarrassing: “Why it is the greatest system in history and how it can become even greater Never before have theory and practice been so relentlessly compared ” Professor Berle deserves better than this rareless job, fatuously presented. ↩