In response to:

We Are All Murderers from the March 3, 1966 issue

To the Editors:

In her review of “The Condemned of Attona” at Lincoln Center, [NYR, Mar. 3] Miss Hardwick raises a question which touches at the essence of the play and which deserves an answer. She notes that “Franz weeps for the starving orphans, the dead cities” (of a postwar Germany he imagines, the very opposite of the real post-war Germany, the land of the Wirtschaftswunder) and goes on to say: “And yet one is not quite sure what Sartre means us to think: Would starving German orphans in 1959 satisfy any moral design?”

The Frenchmen who read the play in the midst of the Algerian war knew very well what Sartre meant them to think. In effect he was saying:—The Nazi torturer, Franz von Gerlach, justified his deeds by projecting a future which never came to pass. You are doing the same thing right now. You condone atrocities or commit them to win victory. You say the victory must be won or the future will be disastrous. Supposing a withdrawal from Algeria will not spell disaster, will not mean starving orphans, raped women, ravaged fields—like the Butcher of Smolensk you will be common criminals.

The starving German orphans in 1959 satisfied the moral design of the Nazi war criminal, just as today the prediction of murdered South Vietnamese and starving orphans in Saigon in the event of a victory by the National Liberation Front satisfied the moral design of those who indulge in napalm bombing and poisoning of rice fields.

Unfortunately, as Miss Hardwick points out (to be specific, in Scene III, Act IV and Scene I, Act V), the reader’s or viewer’s mind is so muddled by the involved plot that it is no longer clear at all what the play is about, at least not here in the U.S. and in 1966. It might be well to point out, therefore, that what the review calls “an indifferent bourgeois drama of German family life” appeared to the French public as a pointed analysis of the problem: to what extent is a war criminal conditioned socially and psychologically? to what extent is he free, and therefore responsible for his acts? Franz, the sane man of the last act who has given up deluding himself, asserts his freedom and independence from his father and thus his full responsibility for the deeds of the Butcher of Smolensk, but the father dies with him and the audience knows that he too has forfeited his life as a human being, he too is responsible for what happened.

Inge S. Marcuse

La Jolla, California

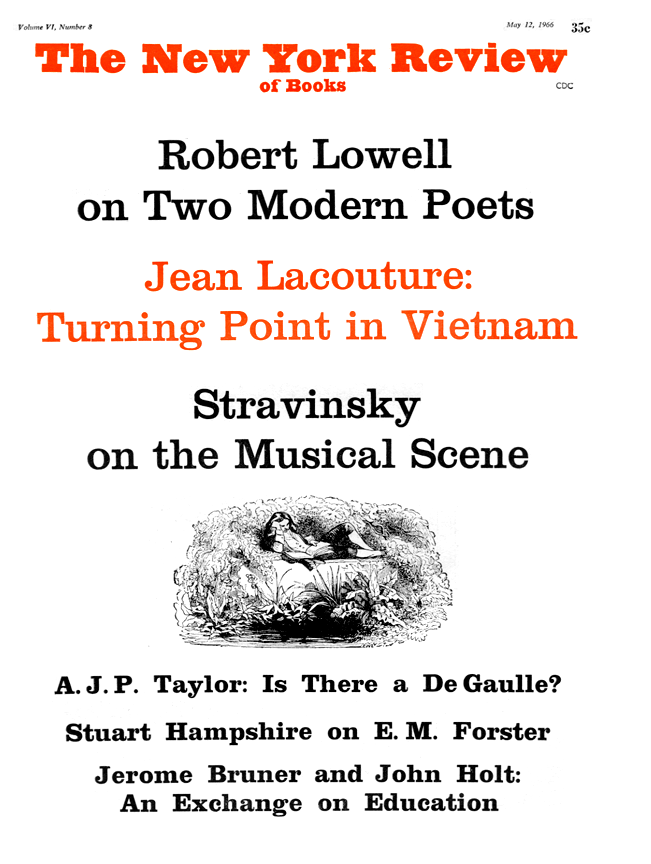

This Issue

May 12, 1966