First came the dream: a society that could be both communist and free—where men could speak and write without fear of punishment, where rewards would be based on merit rather than loyalty, where socialism meant experimentation instead of numbing conformity. That was all they wanted—the Czechs and the Slovaks who last January overturned the Novotny dictatorship. They had no intention of reinstating capitalism, of leaving the Warsaw Pact, of conspiring with “revanchists,” or even threatening the communist party’s political monopoly. Their goal was to humanize a system that had become economically inefficient and bureaucratized—to see whether a Marxist society could be run by consent rather than by intimidation. That was the dream.

Then came the reality: Soviet tanks rumbling across the frontiers, joined by token contingents from East Germany, Poland, Hungary, and Bulgaria. They said they were saving socialism and combatting counter-revolution, which is what they said in Budapest a dozen years ago. What they meant was that they were stopping a gangrenous infection before it spread to the restless states of the Soviet empire and even to Russia itself—the infection of reform and democratization.

Twilight fell once again over Prague, as it did in 1938 when Britain and France told Hitler he could have the Sudetenland, as it did in 1948 when the communists seized total control of a coalition government and transformed a democratic society into a bureaucratic police state. The world stands by today, as it stood by then, as democracy in Czechslovakia, for the third time in a single generation, has become a victim of great power politics.

The sin of the Czech and Slovak reformers—of the writers, journalists, and intellectuals who eagerly joined them, of the millions of quite ordinary people who became actively involved in the remarkable struggle taking place—was that they thought they might be able to build their own form of socialism according to their “national specific features and conditions,” as the Bratislava declaration solemnly affirmed only three weeks before Soviet tanks rolled into Prague. They thought that a Marxist society need not be a prison, that people should be allowed to express unorthodox opinions without losing their jobs or disappearing, that communists do not have a total monopoly on the truth, and that the Soviet road to socialism is not the only one—nor even the one best suited to a nation which knew prosperity and democracy long before it experienced Marxism-Leninism.

They were wrong, and today they are paying the price. Or at least they were wrong in thinking they could get away with it in the shadow of Soviet power, sandwiched between “comradely neighbors” hostile to their experiment in democratization, in their strategically vulnerable position as a corridor linking West Germany to the Soviet Union. The Kremlin was no more willing to tolerate what it believes to be threatening political and social experimentation in Eastern Europe than is the United States in the Caribbean. Where the great powers have staked out their sphere of influence, freedom of maneuver is possible only on the sufferance of the authorities in the seat of empire.

IN A SENSE the handwriting was on the wall all along, but nobody wanted to read it. It was hard to believe that there could be another Budapest. Too much had happened in the world during the past twelve years—the two rival power blocs were gradually loosening at the seams, Moscow and Washington had learned to live together in uneasy symbiosis, and the cold war had degenerated into an institutionalized balance of power. The Czechs and the Slovaks had posed no direct threat to the security of the Soviet state. Not even if they pulled out of the Warsaw Pact—which they had not the slightest intention of doing. The alliance with Russia, confirmed by the Anglo-French betrayal at Munich and cemented by the liberation from the Nazis by the Russians in 1945, is a fact of life. It is, as Alexander Dubcek said before the invasion of his country, “the alpha and omega of our foreign policy.”

An independent communist government in Czechoslovakia today, or even a neutralist non-communist government, is no more a physical threat to the Soviet Union than was a socialist Guatemala to the United States in 1954, a communist Cuba in 1961, or a neutralist Dominican Republic in 1965. But weak states in the shadow of powerful ones enjoy a marginal independence. In principle the Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia was not a great deal different from the landing at the Bay of Pigs, although the force employed was considerably greater and the methods more brutal. Politically they were equally disastrous for the invaders, both of whom apparently convinced themselves that what they were doing would somehow win the support of those they were invading.*

The great powers have shown little tolerance for diversity within what they arrogate to themselves as their sphere of influence, and each respects the right of the other to stamp out whatever heresy it finds inacceptable. The Russians would not have tried to save Castro even had the Bay of Pigs turned into a fullscale American invasion, and the United States has made it clear that it has no intention of intervening in Eastern Europe. The current Russo-American detente, as Dean Rusk and others have stated on numerous occasions, rests upon a mutual respect for the lines of demarcation drawn after the Second World War. The Russians do not encroach on what is generally regarded to be US territory—the Caribbean, Latin America, Japan, Western Europe—and the US does not poach on their sphere of influence in Eastern Europe. Within these recognized spheres, there has been general stability. Trouble has occurred basically in the peripheral areas where both sides are jockeying for advantage: the Middle East and Southeast Asia.

Advertisement

It is argued that the US has behaved with far more tolerance to challenges from within its system of alliances: for example, we have not invaded France although she has virtually withdrawn from NATO. But the parallel is not a convincing one since it ignores geography. Czechoslovakia lies on the invasion route into Russia; France is separated from the United States by an ocean. The parallel with France is Albania, which has persistently defied Moscow, but is geographically so remote and militarily irrelevant (as well as inaccessible to the direct application of Soviet power) that its heresy can be tolerated. The parallel with Czechoslovakia is the Dominican Republic, where the United States launched an invasion to prevent a change of government, and justified it by saying it was on the invitation of certain Dominican leaders, and that unspecified agents of a foreign power threatened to take over the country. Morally the difference was minimal, even though the conditions and the methods cannot be equated.

The system of great power reciprocity has never worked better than during the crisis over Czechoslovakia. It has been reported, on generally good authority, that the Russians launched their invasion only after confirming that the gentlemen’s agreement with the United States on spheres of influence was still valid. Reluctantly Washington replied that it was. In a sense the United States was powerless to do anything about the decision to intervene, once the Russians decided that a compliant regime in Prague was crucial to their interests. But it is also true that very little effort was made to dissuade the Russians, to warn them of the dangers such an invasion would pose to the detente, or to reinforce the arguments of Kremlin doves. Once the intervention came, President Johnson waited a full twelve hours before condemning it. The fact is that Washington, preoccupied with Vietnam and committed to the policy of super-power diplomacy, had no serious interest in rocking the boat over the regrettable but peripheral fate of Czechoslovakia. As Dean Rusk said at his first staff meeting after the invasion, Czechoslovakia did not deserve that much sympathy because she was a major supplier of arms to North Vietnam. The Russians were holding up their part of the unofficial bargain in Latin America; the United States could do no less in Eastern Europe.

THE QUESTION, of course, remains: why did the Russians do it? The official reason was the much-proclaimed threat of counter-revolution, that the reformers were, according to Pravda, “preparing the ground for reorienting the Czechoslovak economy on the West,” that “reactionary, anti-socialist forces which relied on world imperialism for support were rearing their heads in the country,” and that, most dangerously of all, events were “turning the Czechoslovak communist party into an amorphous, ineffectual organization.” Behind these charges lay the more serious unofficial reasons: that the Czechs and the Slovaks had failed to carry out fully the accords reached with Moscow at Cierna, and ratified in the presence of its allies at Bratislava.

While the Cierna accords have never been made public, the Russians allege that Dubcek, as head of the Czechoslovakian communist party, agreed to reimpose press censorship, prevent the formation of political parties outside the communist-controlled National Front, strengthen the army and the militia, halt any purge of conservative communists, and cease all press polemics with the Soviet Union and its allies. In addition the Russians demanded the removal of two leading liberals: Cestmir Cisar, secretary of the central committee, and Frantisek Kriegel, a member of the party presidium. When Dubcek failed, in Moscow’s view, to carry out this agreement, the balance was tipped in favor of those who demanded military intervention to save the situation. What these hard-liners particularly feared was that the Dubcek-led reformers would purge the central committee of Moscow-oriented conservatives at the special party congress scheduled for September 9. Once the central committee was cleared of those opposed to the new reforms, there could be no hope of turning back the clock in Prague without a full-scale military occupation. By beating Dubcek to the draw, the Russians thought they could, with a minimum show of force, restore the situation to what it had been during the Novotny regime. Like Kennedy at the Bay of Pigs, they seem even to have convinced themselves that the majority of Czechs and Slovaks actually wanted to overthrow their government in favor of one more amenable to Moscow’s wishes.

Advertisement

The Russians were clearly contemplating military intervention for several months, and the long refusal to pull their troops out of Czechoslovakia following Warsaw Pact maneuvers was designed to intimidate the reformers. At Cierna they thought they could separate the liberals from the conservatives and impose a harsh settlement. When this split failed to materialize, however, they agreed to a compromise that accepted the basic principles of the reform movement. A few days later their allies were brought in at Bratislava to ratify the accords, and there were strong objections from Gomulka, Ulbricht, and Zhivkov of Bulgaria. But the agreement was signed, and when the Czechoslovak leaders returned to Prague, they believed that the danger of invasion had been surmounted. To placate the Soviets, Dubcek discouraged popular demonstrations during the brief state visits of Tito and Ceausescu, and told the press to tone down its criticisms of the hard-line regimes in Warsaw, East Berlin, and Moscow. The tide turned on August 12 at Karlovy Vary, where Ulbricht demanded that Dubcek live up to the Bratislava agreements, while the Czechoslovak leaders argued for the principle of noninterference in the internal affairs of communist states. From that moment on the conservatives in the Czechoslovak party presidium and central committee dug in their heels, and the hawks in the Kremlin became convinced that they could not tame Prague without a military intervention.

The final decision to intervene was made not because there was a misunderstanding over the terms reached at Cierna, but because the Soviets and their allies feared that the Czechoslovak defection from Communist orthodoxy would imperil the solidity of the alliance and spread heresy to their own lands. They saw the experiment of the Czechs and Slovaks not as a variation within the socialist system, but as an infection that could undermine their conception of what a communist state should be. They believed it would weaken the communist party’s control over the state apparatus and unleash an uncontrollable range of opinion. In a sense they were right. Even in the most rigidly authoritarian states, such as Poland and East Germany, not to mention the Soviet Union itself, there are forces pushing for a loosening of arbitrary economic controls and for greater freedom of expression. The intellectuals, scientists, and technicians, the “new class,” of these societies are increasingly resistant to the dogmatism of the party bureaucracy and the arbitrary controls exercised by the apparatchiks. While committed to the values of socialism, they, like the Soviet physicist Sakharov, in his remarkable manifesto, are beginning openly to demand greater freedom of expression and artistic creation and to repudiate the neo-Stalinist restrictions. When Prague eliminated press censorship, encouraged freedom of discussion and the confrontation of ideas, allowed the creation of non-communist political groups, and tried to make the bureaucracy responsive to the vocalized demands of the hitherto silent population, East European liberals were heartened.

But the orthodox communist leaders in the Soviet Union, Poland, and East Germany decided that the situation was getting out of hand. It was not so much that they distrusted Dubcek’s motives as his ability to keep in check the political and social forces unleashed in Czechoslovakia. They were alarmed by the free-wheeling iconoclasm of journals like the literary-political weekly Literarni Listy, which played a crucial role in the liberalization drive. The magazine became a spearhead of the Czechoslovak revolution, and its circulation shot up to over 300,000 in a nation of only fourteen million. Three of its editors had been expelled from the party last fall for their attack on the Novotny regime, and one of them, Ludvik Vaculik, later wrote the famous manifesto, “Two Thousand Words,” signed by leading intellectuals in support of the reformers. Prodding the Dubcek leadership from below and openly satirizing such unsympathetic foreign comrades as Ulbricht, the magazine symbolized everything orthodox communists feared from the reform movement.

THIS WAS SIMPLY the most outspoken element of an attitude that had deep roots in the communist party itself. It is precisely what was unique about the Czechoslovak experiment—that it came from within the ranks of the party hierarchy. The reformers were dedicated Marxists, dissatisfied with the rigidity of the party structure and eager to breathe new life into ossified, bureaucratic institutions. They wanted to make the economy work more efficiently, reward initiative, and decentralize the economic machinery. They resented the unequal trading relationships with the Soviet Union, where they processed Russian raw material at little benefit to themselves, and they wanted to expand economic links with the West so that they could modernize their outdated industrial plant. While it had been the most industrialized state of Eastern Europe before the war, Czechoslovakia had fallen behind such neighbors as Austria. In many cases its industry had become inefficient, outdated, and uncompetitive—locked in the communist trading bloc, but unable to operate on the world market. The economic crisis had become so severe that Novotny was forced to accept some of the reforms proposed by Professor Ota Sik, including production geared to demand, and the decentralization of authority.

But the reforms were being held up by economic conservatives with a vested interest in the status quo. Last year the regime resumed its repression of intellectuals, and the Slovaks became increasingly resentful of their domination by the Czech majority in Prague. With only four million of the country’s fourteen million people, the Slovaks have felt discriminated against by the more numerous, industrially advanced Czechs. Considering themselves to be a separate nation, with a somewhat different language and different historical and social traditions, the Slovaks have never assimilated easily into the hybrid state formed in 1918 at the break-up of the Austro-Hungarian empire. Where Prague had been administered by Vienna, the Slovak capital of Bratislava was absorbed in the Hungarian part of the empire, and the differences have been crucial.

During the Stalinist terror of the early 1950s the Slovaks, with the few remaining Jews, were singled out as “bourgeois nationalists,” and repressive efforts made to ignore or stamp out their separate identity. Even after the terror, Slovakia was treated more like a colony than a theoretically equal member of a federated state. Novotny was particularly contemptuous of Slovak feelings and became an object of contempt for both nationalists and reformers. Resistance to his regime became centered in Bratislava, where the Writers’ Union demanded a purge of Stalinists, the release of political prisoners, and an abolition of censorship. When the Czechs realized this involved more than simply an expression of Slovak nationalism, they joined forces with their colleagues and sparked a whole progressive movement.

FACED with the resentment of the Slovaks, the demands of the intellectuals, and its own economic failures, the Novotny regime began to crack around the edges. It needed only a push to crumble, and that push came in October 1967 when the relatively obscure first secretary of the Slovak communist party stood up in the meeting of the Central Committee and attacked the Novotny leadership. Progressives and conservatives rallied around Alexander Dubcek, including a majority of workers. After a bitter struggle Novotny was ejected first as head of the party, and then as President. Once the rotting foundation had been removed, the barriers fell faster than anyone could have anticipated. Within a few months freedom of the press was restored, political prisoners liberated and rehabilitated, the economy decentralized and opened to the play of market forces, and the communist party itself democratized to provide for secret ballots and minority criticisms of majority decisions. Although he began as a moderate reformer, Dubcek himself was caught up in the tide and became a leading advocate of democratization.

From the 5th of January, when Novotny was ejected from office, to the 21st of August, when Russian tanks rolled across the frontiers, Czechoslovakia experienced an exhilarating freedom. People who had been circumspect, or even silent, for a generation, suddenly were able to voice their feelings. Workers held debates on the streets, housewives stood in line to sign petitions, the press cast off two decades of censorship and began subjecting the government to a blinding scrutiny. Various non-party groups were allowed to form, such as Club 231, of former political prisoners, and KAN, an organization of non-party political activists. While they posed no counter-revolutionary threat, some of their members spoke of the day when the communist party might be willing to compete for power with a non-communist party. The communists, after all, had won 38 percent of the vote in 1947 during Czechoslovakia’s last free election.

“The creation of an opposition party in Czechoslovakia is a necessity,” stated the young playwright Vaclav Havel, “and this party should enjoy the same rights and the same chances as the communist party.” This was also the position of Ivan Klima, one of the three writers temporarily evicted last fall from the communist party by Novotny. “The press can remain free,” he wrote in Literarni Listy, “only within a functioning democratic system, and this is scarcely imaginable without the existence of several independent political parties.” Other reformers, however, argued…that this was unrealistic, given the political situation in Czechoslovakia, and its relation with the Soviet Union. Even such an outspoken liberal as Professor Eduard Goldstücker, president of the Writers’ Union, has argued that “a parliamentary opposition as a system for the control of power exists only in a class society. Since Czechoslovakia has gone beyond the struggle between classes, we have to find and create another system for controlling power.”

THE GOVERNMENT LEADERS did not want to break the communist party’s monopoly on power, but simply, in Dubcek’s words, to eliminate “the discredited bureaucratic-police methods”—to infuse communism with the humanism that had been lost in decades of conspiracy and repression. They realized that what they were proposing was radical—dangerously so in the eyes of the Soviet Union and its allies—and they were not sure they would be able to get away with it. We knew there were risks involved in the “effort toward social renewal,” Josef Smrkovsky, president of the National Assembly told the Czechoslovak people after returning from his abduction to Moscow, “but we never thought we would have to pay the price we paid the night of August 20-21.” That price was a return to communist orthodoxy, reimposition of censorship, permanent stationing of Soviet troops on the West German frontier, dissolution of non-communist political groups. Nobody wanted to admit it, yet all along the reformers realized in the back of their minds that they might not be able to get away with their experiment.

“What we are trying to do here,” one of the most outspoken advocates of the reform movement told me in Prague just two weeks before the invasion, “is to find a form of communism that is relevant to advanced, technological societies where people have to be given the latitude to think for themselves. This is the only kind of communism that is ever going to have any appeal to Western Europe. The reform-minded parties in Italy, and even in France, are with us. But I’m afraid the Russians aren’t ready to understand what we are doing. They see it as a threat to their own system, and so they accuse us of being ‘counter-revolutionaries’—which means that we don’t slavishly imitate their ways. They know we’re not going to embrace the West Germans or apply for membership in NATO. But they are afraid that our ‘heresy’ of free speech and non-communist political groups might infect their own citizens. Beneath the crust of neo-Stalinism, the Soviet Union is seething with the demand for reform. If the Czechs and Slovaks can get away with this ‘heresy,’ why not the citizens of the Soviet Union, Poland, and East Germany? That’s the question the Russians are asking themselves, and I’m afraid what the answer might be.”

In the balmy air of an early August night in Prague, the warning seemed a bit exaggerated. With Czech hippies playing their guitars on the baroque Charles Bridge, with rock-and-roll music wafting through the streets from student discotheques, and with the moon rising above the spire of Hradcany Castle, the prospect of a Soviet military intervention seemed highly improbable. But Prague is a city where dreams can turn into nightmares, and Hradcany is also the Castle that tormented Kafka’s Josef K. Central Europe is not a place for easy optimism. The history of the Czechs and the Slovaks is riddled with failure and betrayal: the burning of Jan Hus at the stake in 1415, the defeat of the Reformation army at the Battle of the White Mountain in 1620, the stab in the back at Munich.

It is not so remarkable that the Czechs and the Slovaks failed to retain everything they won during the exhilarating months since the Novotny dictatorship collapsed last January. The Soviet Union simply behaved with the arrogance and the blindness of a super-power that knows it has a free hand within the area it claims as its sphere of influence. What is remarkable is that the people of Czechoslovakia, by bravely defying the occupiers without militarily provoking them, by painting swastikas on their tanks and telling the Russian farm boys to go home, and by supporting their ousted and imprisoned leaders, have for the time being been able to retain a considerably greater degree of autonomy than anyone would have imagined when the Russian military machine first struck. They have so far kept their reformist leaders—Dubcek, Svoboda, Cernik, Smrkovsky—because the Soviets were unable to find any reputable Quislings to carry out their orders. The hands of the reformers are now tied, the secret police is silencing opposition, and the people have once again retreated into stony silence. But Russian military government has been averted, for the time being at least, and in the long run the Czechs and the Slovaks are likely to win back some of their reforms, just as the Hungarians did after the brutal invasion of 1956.

This is not the end of the story of revolution within the communist empire, but only the beginning. The forces of reform and democratization which have been released in Czechoslovakia, and momentarily restrained by Soviet military power, are not unique to that country. They exist in Poland, where stagnation and political repression have created great instability beneath surface conformity; in East Germany, where even the Ulbricht regime has not been able to silence support for the Czechoslovak liberals; and in the Soviet Union itself, where the new technocracy and the intelligentsia have grown increasingly restive under the reactionary, autocratic rule of the party bureaucrats who replaced Khrushchev. The system of political repression practiced by the Soviet Union and its orthodox allies could not withstand the kind of public criticism that was the hallmark of the Czechoslovak reform program. The Soviet system demands authoritarianism at home and obedience of national communist parties abroad.

BUT THIS SYSTEM, which was workable during the time when the Soviet Union could with some justice claim to be the leader of the world communist movement, is now in ruins. It is not world communism which has suffered from the invasion of Czechoslovakia—for there is no longer any single seat of communist authority—but the Soviet Union. The prestige it has enjoyed within the communist movement has been shattered, and it has revealed itself to be simply another dynastic state with dynastic ambitions. Moscow, not Prague, is the greatest casually of the intervention against the Czech and Slovak reformers, and its actions have been repudiated by the major European communist parties, including the French, the Italians, the Yugoslavs, and the Rumanians. Instead of postponing the coming crisis within the Soviet Union and its hard-line allies, the move against Prague has hastened it by polarizing opinion in the communist states. Unity within the communist world was long ago destroyed; it is now being broken down within the repressive communist bureaucracies of Eastern Europe.

The initial reaction in the West to the Russian intervention was a call for greater vigilance against the “communist conspiracy” and for increased arms budgets to meet the Soviet threat. Even the normally liberal Times of London hoisted the cold war flag and called for the Western powers to “look seriously at the state of their defenses.” Many fear that the cold warriors here and abroad will get a new shot in the arm, and the détente will be seriously imperiled. This may be exaggerated. The Russians pose no more a threat to the West than they did two days, or two months, or two years ago. They are neither more aggressive nor more pacific. They simply want to hold on to the empire they believe is rightly theirs and which they consider vital to their security. No political leader in Washington has challenged this principle, even though they all lament its implementation. The truth is that Washington is willing to let Moscow play its game, so long as the Russians do not infringe on our territory. The détente is unlikely to be endangered because both political parties are committed to it and respect super-power diplomacy. Washington will forget Czechoslovakia even faster than it forget Budapest. But it has a vested interest in the détente, regardless of which party is in power.

Revolutions of the kind that occurred in Czechoslovakia are troublesome to the super-powers. They cannot accept them without undermining their control over their client states and eroding their traditionally conceived spheres of influence. They cannot intervene forcibly against them, however, without diminishing their international prestige and, perhaps more importantly, unleashing disruptive forces within their own societies. This is what the United States learned at Santo Domingo and in Vietnam, and it is what the Soviet Union is now discovering in Czechoslovakia.

The Czechs and the Slovaks had their moment of glory, and they will have it again. For the time being they must play the good soldier Schweik and sit out the storm that is now enveloping them. But their vision of a humane communist society was an inspiring one that will have a profound impact on nations that are trying to achieve social justice without undergoing a brutalizing dictatorship. In the Soviet empire itself, the rumbling echoes of the Czechoslovak heresy have only just begun to be heard.

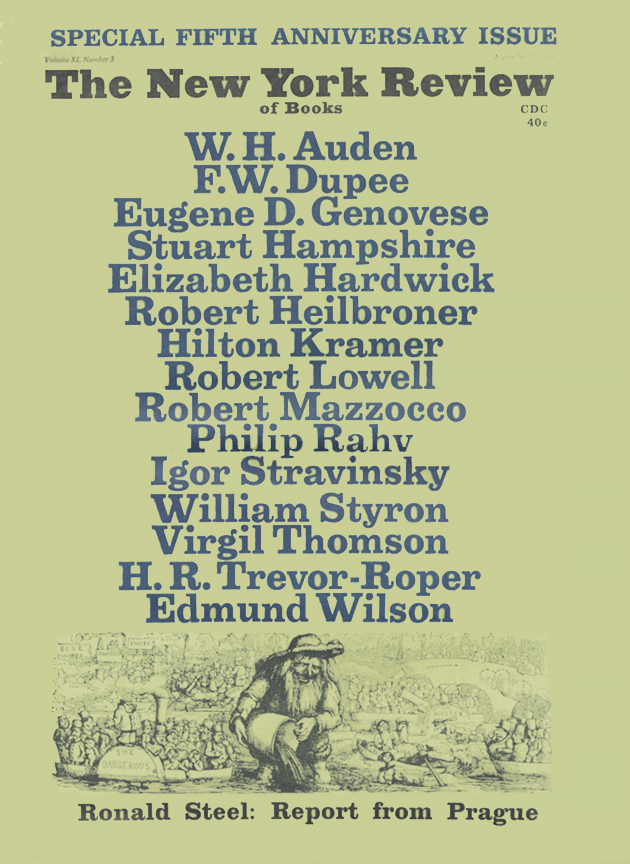

This Issue

September 26, 1968

-

*

The cover story issued by the Russians, that they were responding to a plea for help by Czechoslovak leaders, resembles the story issued by the CIA at the Bay of Pigs. In The Invisible Government, Wise and Ross recount the following episode: ↩