After more than twenty years as a folk leader, one of the Negro shepherd-kings of the Caribbean, Robert Bradshaw of St. Kitts—“Papa” to his followers—is in trouble. Two years ago he became the first Premier of the three-island state of St. Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla. The state had a total area of 153 square miles and a population of 57,000. It has since become smaller. Anguilla has seceded and apparently gone for good, with its own islet dependencies of Scrub Island, Dog Island, and Anguillita: a loss of 35 square miles and 6000 people. There is discontent in Nevis, 50 square miles. In St. Kitts itself, Papa Bradshaw’s base, there is a dangerous opposition.

The opposition union is called WAM, the opposition political party PAM. WAM and PAM: it is part of the deadly comic-strip humor of Negro politics. These are still only the politics of kingship, in which there are as yet no rules for succession. It is only when leaders like Papa Bradshaw are in trouble, when they are threatened and fight back, that they become known outside their islands; and it is an irony of their kingship that they are then presented as dangerous clowns. Once Papa Bradshaw’s yellow Rolls-Royce was thought to be a suitable emblem of his kingship and courage, a token of Negro redemption. Few people outside knew about the Rolls-Royce; now it is famous and half a joke.

The folk leader who has been challenged cannot afford to lose. To lose is to be without a role, to be altogether ridiculous.

“Papa Bradsha’ started something,” a supporter says. “As long as he lives he will have to continue it.”

Bradshaw prepares to continue. The opposition are not allowed to broadcast; their supporters say they do not find it easy to get jobs. Men are recruited from the other Caribbean islands for the police. The St. Kitts army, called the Defence Force, is said to have been increased to 120; Papa Bradshaw is the Colonel. There are reports of a helicopter ready to police the island’s sixty-eight square miles.

It has been played out in other countries, this drama of the folk-leader who rules where he once securely agitated and finds that power has brought insecurity. In St. Kitts the scale is small, and in the simplicity of the setting the situation appears staged.

Think of a Caribbean island roughly oval in shape. Indent the coastline: beaches here, low cliffs there. Below the sharp and bare 4000-foot peak of a central mountain chain there is forest. Then the land slopes green and trimmed with sugarcane, uncluttered with houses or peasant allotments, all the way down to the sea. A narrow coast road encircles the island; it is impossible to get lost. The plantation workers live beside this road, squeezed between sugarcane and sea. Their timber houses are among the tiniest in the world.

All the history of St. Kitts is on this road. There, among those houses on low stilts, whose dirt yards run down through tangled greenery to the sea, Sir Thomas Warner landed in 1623, to found the first British colony in the West Indies. Here, in the barest opening in the sugarcane, are two rocks crudely carved by the aboriginal Caribs, whom the English and the French united to exterminate just there, at Bloody River, now a dip in the road. Sir Thomas Warner is buried in that churchyard. Not far away are the massive eighteenth-century fortifications of Brimstone Hill, once guarding the sugar-rich slave islands and the convoys that assembled in the calm water here for the run to England. The cannons still point; the site has been restored.

In the southeast the flat coastal strip broadens out into a little plain. Here, still set in the level green of sugarcane, are the airstrip and the capital, Basseterre. There is one vertical in this plain: the tall white chimney of the island’s single sugar factory.

The neatness and order is still like the order of the past. It speaks of Papa Bradshaw’s failure. He hasn’t changed much. His fame came early, as an organizer of the sugar workers; a thirteen-week strike in 1948 is part of the island’s folklore. But Bradshaw’s plantation victories mean less today to the young. They do not wish to work on the plantations. They look for “development”—and they mean tourism—on their own island. The air over nearby Antigua rocks with “Sunjets” and “Fiesta Jets.” St. Kitts only has brochures and plans; the airfield can only take Viscounts. It is unspoiled; the tourists do not come. The feeling among the young is that Papa Bradshaw has sold out to the sugar interests and wants no change.

And Bradshaw’s victories were only of St. Kitts. They meant little to the peasant farmers of Nevis, and nothing to the long-independent farmers and fishermen of Anguilla, seventy miles away. The Nevisians and Anguillans never voted for Bradshaw. Bradshaw didn’t need their votes, but he was irritated. He said he would put pepper in the soup of the Nevisians and bones in their rice; he would turn Anguilla into a desert and make the Anguillans suck salt. That was eleven years ago.

Advertisement

“Gahd bless Papa Bradsha’ for wa’ he do.” It is only the old and the devout among the plantation Negroes in St. Kitts who say that now. They remember the ola or trash houses, the cruel contract system, the barefoot children and the disease. Bradshaw himself worked as a young man in the Basseterre sugar factory; he carries a damaged hand as a mark of that service. Like many folk leaders, he never moved far beyond his first inspiration. It is also true that, like many folk leaders, he is responsible for the hope and the restlessness by which he is now, at the age of fifty-one, rejected.

The weatherbeaten little town of Basseterre also has a stage-set simplicity. There is a church at the end of the main street. PAM hangs its home-made board in the verandah of a rickety little house. Directly opposite is a building as rickety, but larger; this is labeled “Masses House” and is the headquarters of the Bradshaw union. At times of tension this section of the main street is known as the Gaza Strip.

Masses House has a printery which every day runs off 1200 copies of a ragged miniature newspaper called The Labour Spokesman. Even with large headlines there isn’t always enough news to fill the front page; sometimes a joke, headlined “Humour,” has to be added. Sport is good for a page or two or three. A cricketer like Sobers can make the local sportswriter ambitious. “The shy boy of seventeen, not yet lost his Mother’s features on his debut against England in the West Indies in 1954, has probably rose to the pinnacle of being the greatest Cricketer both of our time and the medieval age. If W. G. Grace were to twitch in his grave at the comment he would only turn over on the other side to nod his approval.”

A few doors away from Masses House is “Government Headquarters,” a modernistic building of three storeys. Gray air conditioners project from its façade; a pool in the patio is visible through the glass wall. The hotel is opposite, a converted old timber house. The manager is a gentle second-generation Lebanese whose nerves have been worn fine by the harassments of his large family, his staff, untrained or temperamental, the occasional assertive Negro group, and the political situation. “Have you seen our Premier, sir?” He supports Bradshaw but avoids controversy; he knows now he will never see Beirut.

A short side street leads to Pall Mall Square: the church, the timbered colonial-Georgian Public Library and Court, the St. Kitts Club, the private houses with lower floors of masonry, upper floors shingled, white and fragile, and steep four-sided roofs. The garden is unkempt, the wire fences around the central Victorian fountain trampled down, the lamp-standards empty and rusting; but the trees and flowers and the backdrop of mountains are still spectacular. Pall Mall Square is where PAM holds its public meetings. It is also, as all St. Kitts knows, the place where, among trees and flowers and buildings like these, “new” Negroes from Africa were put up for auction, after being rested and nourished in the importers’ barracoons, which were there, on the beach, not far from today’s oil-storage tanks.

The past crowds the tiny island like the sugarcane itself. Deeper and deeper protest is always possible.

At about ten every morning the guards change outside Government Headquarters. The green-bereted officer shouts, boots stamp; and the two relieved soldiers, looking quickly up and down the street, get into the back of the idling Land-Rover and are driven to Defence Force Headquarters, an exposed wooden hut on high ground near ZIZ, the one-studio radio station.

Against the soft green hills beyond Basseterre, the bright blue sea and the cloud-topped peak of Nevis, a Negro lounges about in a washed-out paratrooper’s uniform, thin and bandylegged, zipped-up and tight, like a soft toy.

It seems to be drama for the sake of drama. But there are bullet marks on the inside wall of the hut. These are shown as evidence of the armed raid that was made on Basseterre by persons unknown in June 1967, at the beginning of the Anguillan crisis. The police station was also attacked. Many shots were fired but no one was killed; the raiders disappeared. Bradshaw added to his legend by walking the next morning from Government Headquarters to Masses House in the uniform of a Colonel, with a rifle, bandolier, and binoculars.

Advertisement

The raid remains a mystery. Some people believe it was staged, but there are Anguillans who now say that they were responsible and that their aim was to protect the independence of their island by kidnapping Bradshaw and holding him as a hostage. The raid failed because it was badly organized—no one had thought about transport in Basseterre—and because Bradshaw had been tipped off by an Anguillan businessman.

Days after the raid leading members of PAM and WAM were arrested. They went on trial four months later. Defense lawyers were harassed. Bradshaw’s supporters demonstrated when all the accused men were acquitted. Ever since, the rule of law in St. Kitts has appeared to be in danger. The definition of power has become simple.

I see them:

These bold men; these rare men—

Above all other men that toil—

That LIVE the truth; that suffer:

These policemen. We love them!

The poem is from The Labour Spokesman. There may no longer be a danger from Anguilla, but the police and the army have come to St. Kitts to stay.

I first saw St. Kitts eight years ago, at night, from a broken-down immigrant ship in Basseterre harbor. We didn’t land. The emigrants had been rocking for some time in the bay in large open boats. The ship’s lights played on sweated shirts and dresses, red eyes in upturned oily faces, cardboard boxes and suitcases painted with names and careful addresses in England.

In the morning, in the open sea, the nightmare was over. The jackets and the ties and the suitcases had gone. The emigrants, as I found out, moving among them, were politically educated. Copies of The Labour Spokesman were about. Many of the emigrants from Anguilla, which had been recently hit by a hurricane; were in constant touch with God.

The emigrants had a leader. He was a slender young mulatto, going to England to do law. He moved among the emigrants like a trusted agitator; he was protective. He was a man of some background and his political concern, in such circumstances, seemed unusual. He mistrusted my inquiries. He thought I was a British agent and told the emigrants not to talk to me. They became unfriendly; word spread that I had called one of them a nigger. I was rescued from the adventure by a young Baptist missionary.

I didn’t get the name of the shipboard leader then. In St. Kitts and the Caribbean he is now famous. He did more than study law. He returned to St. Kitts to challenge Bradshaw. He founded PAM. He has been jailed, tried, and acquitted; he is only thirtyone. He is Dr. William Herbert. A good deal of his magic in St. Kitts, his power to challenge, comes from that title of Doctor—obtained for a legal thesis—which he was then traveling to London to get.

He came into the Basseterre hotel dining-room one morning. As soon as we were introduced he reminded me of our last meeting. The ship, he said, was Spanish and disorganized and he was young. He was as restless and swift and West Indian-handsome as I had remembered: his five months in jail have not marked him.

“I don’t want to frighten you,” he said, when he came to see me later that day. “But you should be careful. Writers can disappear. Two soldiers will be watching the hotel tonight.”

We drove to a rusting seaside bar, deserted, a failed tourist amenity.

“Have you seen Bradshaw?”

I said that the feeling in Government Headquarters was that I might be a British agent. Mr. Bradshaw wouldn’t give an interview, but he had come over to the hotel one morning to greet me.

“He’s an interesting man. he knows a lot about African art and magic and so on. It perhaps explains his hold, you know.”

We went to look at Frigate Bay, part of the uninhabited area of scrub and salt-ponds which is attached like a tail to the oval mass of St. Kitts. The government had recently announced a £29-million tourist development for Frigate Bay. Some in-transit cruise passengers had been taken to inspect the site a few days before; The Labour Spokesman had announced it as the start of the tourist season.

“Development!” Herbert said, waving at the desolation. “If you come here at night they shoot you, you know. It’s a military area. They say we are trying to sabotage.”

On the way back we detoured through some Basseterre slum streets. Herbert waved at women and children. “How, how, man?” Many waved back. He said it was his method, concentrating on the women and children; they drew the men in.

Herbert is the first and only Ph.D. in St. Kitts. Beside him, Bradshaw is archaic, the leader of people lifted up from despair, the man of the people who in power achieves a personal style which all then feel they share. In St. Kitts and the West Indies Bradshaw is now a legend, for the gold swizzle-stick he is reputed to bring out at parties to stir his champagne, the gold brush for his moustache, the formal English dress, even the silk hose and buckle shoes on some ceremonial occasions, the vintage yellow Rolls-Royce. He has a local reputation for his knowledge of antiques and African art and for his book-reading. He is believed to be a member of several book clubs. He reads much Winston Churchill; his favorite book, his PRO told me, is The Good Earth; his favorite comic strip, Li’l Abner.

It is an attractive legend. But I found him subdued, in dress and speech. I was sorry he didn’t want to talk more to me; he said he had suffered much from writers. I understood. I looked at his moustache and thought of the gold brush. He is well-built, a young fifty-one, one of those men made ordinary by their photographs. We talked standing up. His speech was precise, very British, with little of St. Kitts in his accent. He stood obliquely to me; he wore dark glasses. As we walked down the hotel steps to the Land Rover with his party’s slogan, “Labour Leads,” he told me he was pessimistic about the future of small countries like St. Kitts. He worked, but he was full of despair. He had supported the West Indian Federation, but that had failed. And it is true that Bradshaw began to lose his grip on St. Kitts during his time as a Minister in the West Indian Federal Government, whose headquarters was in Trinidad.

The Negro folk-leader is a peasant leader. St. Kitts is like a black English parish, far from the source of beauty and fashion. The folk leader who emerges requires, by his exceptional gifts, to be absorbed into that higher society of which the parish is a shadow. For leaders like Bradshaw, though, there is no such society. They are linked forever to the primitives who were the source of their original power. They are doomed to smallness; they have to create their own style. Christophe, Emperor of Haiti, creator of a Negro aristocracy with laughable names, came from this very island of St. Kitts, where he was a slave and a tailor; the inspiration for the Citadel in Haiti came from those fortifications at Brimstone Hill beside the littoral road.

The difference between Herbert and Bradshaw is the difference between Herbert’s title of Doctor and Bradshaw’s title of Papa. Each man’s manner seems to contradict his title. Herbert has none of Bradshaw’s applied style. His out-of-court dress is casual; his car is old; the house he is building outside Basseterre is the usual St. Kitts miniature. His speech is more colloquial than Bradshaw’s, his accent more local. His manners are at once middle-class and popular, one mode containing the other. He never strains; he moves with the assurance of his class and his looks. To all this he adds the Ph.D.

“Tell me,” Bradshaw’s black PRO asked with some bitterness, “who do you think is the more educated man? Herbert or Bradshaw?”

It would have been too sophisticated a question to the young and newly educated who went to Herbert’s early lectures on economics, law, and political theory in Pall Mall Square.

“Studyation is better than education,” Bradshaw said, comforting his ageing illiterates from the canefields. It became one of his mots.

But Herbert grew as the leader of literate protest. Everything became his cause. New electricity rates were announced: large users were to pay less per unit. Standard practice in other countries, but Herbert and PAM said the new rates were unfair to the poor of St. Kitts. The poor agreed.

Bradshaw and one of his ministers became law students; Bradshaw was almost fifty. The faded notifications of their enrollment in a London Inn are still displayed in the portico of the Court in Pall Mall Square; both men were said to be eating dinners during their official trips to London. Then Anguilla seceded; PAM and WAM were as troublesome as their names; the world press was hostile. Herbert, jailed, tried, acquitted, became a Caribbean figure. Bradshaw was isolated. He appeared to be on the way out. But then he recruited a young St. Kitts lawyer lecturer as his Public Relations Officer.

This man has saved Bradshaw, and in a few months he has given a new twist to St. Kitts politics. Bradshaw’s tactics have changed. He is no longer the established leader on the defensive, attracting fresh agitation. He has become once again the leader of protest. It is in protest that he now competes with Herbert. The young PRO has provided the lectures and the intellectual backing. He is known to the irreverent as Bradshaw’s Race Relations Officer. The cause is Black Power.

The avowed aim is the dismantling of that order which the geography of the island illustrates. The word the PRO sometimes uses is Revolution. The word has got to the white suburb of Fortlands and the Golf Club, where the little group of English expatriates is known as the Whisperers.

Someone put it like this: “What Bradshaw now wants to do is to make a fresh start, with the land and the people.”

The politics of St. Kitts today, opaque to the visitor looking for principles and areas of difference, become clearer as soon as it is realized that both parties are parties of protest, in the vacuum of independence; and that for both parties the cause of protest is that past, of slavery. What is at stake is the kingship, and this has recently been simplified. The difficult message of Black Power—identity, economic involvement, solidarity, as the PRO defines it—has become mangled in transmission. It can now be heard that Bradshaw, for all the English aspirations of his past, is a full-blooded Ashanti. Herbert is visibly mulatto.

Herbert’s father was Labour Relations Officer for the sugar industry at the time of Bradshaw’s famous thirteen-week strike. It was a difficult time for the Herbert family. They were threatened and abused by the strikers; and the St. Kitts story is that Herbert, still a boy, met Bradshaw in the street one day and vowed to get even. Herbert says the meeting may have taken place, but he doesn’t remember it.

I asked him now whether power in St. Kitts was worth the time, the energy, the dangers.

“A man is in the sea,” Herbert said. “He must swim.”

There is still a Government House in St. Kitts, a modest, wide-verandahed timber house on an airy hill. The butler wears white; a lithograph of a local scene, a gift of the Queen, hangs in the drawing-room; there is a signed photograph of the Duke of Edinburgh. The governor is a Negro Knight from another island, a much respected lawyer and academic. He is without a role; he is isolated from the local politics of kingship, this fight between the lawyers, in which the rule of law will go. He has spent much of his time in Government House working on a study of recent West Indian constitution-making. It is called The Way to Power.

The PRO on whom Bradshaw depends, the lawyer-lecturer to whom he has surrendered part of his power, is Lee Moore, a short, slight, bearded country-born Negro of about thirty. He is extremely black with moist, red eyes that fill easily with suspicion. Herbert dismisses him as someone who overdoes the melodrama and is just “playing bad.” But Moore is obsessed with Herbert. He says that in London Herbert used to mock Moore for being a fake Englishman, for attempting an English accent and preferring white company. But it is Herbert, Moore says, who, on the boat to Nevis, always sits down with white people, after shaking hands with all the blacks.

Moore says that when he came to St. Kitts from London he rejected the view—the source can be guessed—that what was needed in St. Kitts was a Negro aristocracy. But the political usefulness of Black Power was only accidentally discovered, in the excitement that followed a lecture he gave on the subject. Herbert’s supporters accused Moore of racialism; and people telephoned Mrs. Moore to ask what color she was. Mrs. Moore is of mixed race and olive-skinned. What people didn’t know, Moore says, is that Mrs. Moore considers herself black.

Now, like Herbert, Lee Moore drives around the circular St. Kitts road, mixing law business with campaigning, waving, mixing gravity with heartiness. On his car there is a sticker, cut out from a petrol advertisement: Join the Power Set.

I made a tour with him late one afternoon. Shortly after nightfall we had a puncture. He was unwilling to use the jack; he said he didn’t know where to put it. He crouched and peered; he was confused. Some cars went by without stopping. I began to fear for his clothes and dignity. Then two cyclists passed. They shouted and came back to help. “We thought it was one of those brutes,” one of them said. A van stopped. The jack wasn’t used. The car was lifted while the wheel was changed.

Moore was in a state of some excitement when we drove off again, and it was a little time before I understood that it was an important triumph.

“It’s how I always change a wheel. Did you hear what those boys on the cycles shouted? ‘It’s Lee Moore’s car.’ ”

Power, the willing services of the simple and the protecting: another man of the people in the making, another Negro on the move.

After a while he said reflectively, “If it was Herbert he would still be there, I can tell you.”

Herbert, though, might have used the jack.

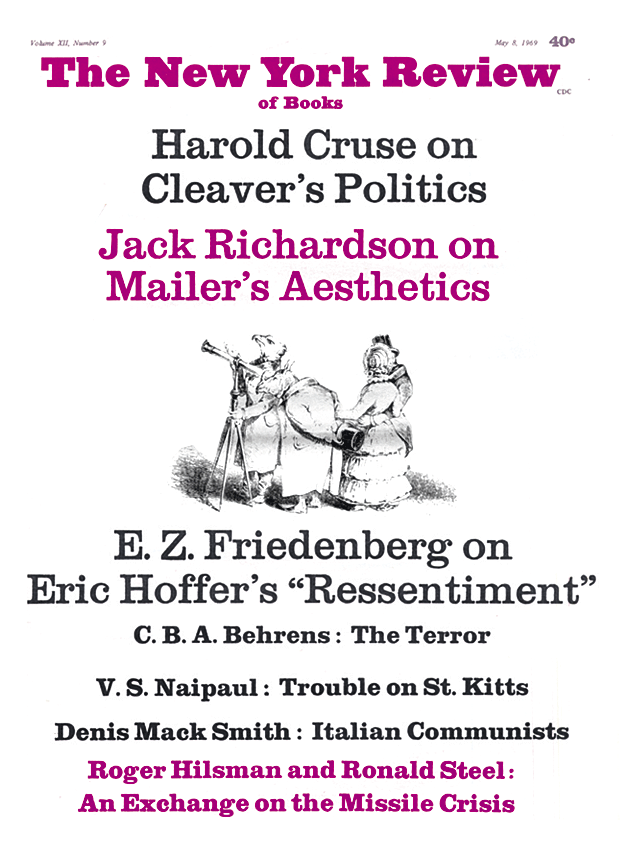

This Issue

May 8, 1969