At a particularly edgy moment between husband and wife in Paul Goodman’s Five Years, a weighty journal of the lean Fifties when Goodman was already “over the hill” and “unwanted,” he shouts, “bitterly”: “You write twenty books and get the reception that I’ve gotten. Do you think it’s like putting on your hat?” During those dispiriting days, with at least two decades of social and literary activity behind him, spartanly supporting himself and his family on little more than a few thousand dollars a year, Goodman was shaken with the belittling thought that the most “expressive relation” to an America of “venality and folly,” “to that stingy world,” he could possibly manage was “to be spitefully Utopian, to bawl.” Still—and it is characteristic of his extraordinary career, characteristic of how we are swept in and out of fashion—lachrymose or not, wretched or not, he wrote. “Who speaks of victory?” asks Rilke. “Survival is all….”

A forgotten anarchist from the era of the patrician Roosevelt, Paul Goodman absurdly (and perhaps not so absurdly) at long last “arrives”—as, among other things, a guru of the young—during the era of the neopatrician Kennedy. Brave and beautiful (morally, not physically—among the many images of himself, probably the one Goodman most enjoys polishing is that of the Socratic seducer: what do these students and strangers see in “my tired face” and “missing teeth” and “near-sighted eyes,” he asks himself, and on occasion answers himself, too: “People say otherwise,/but lust is the magnet of beauty”), spikey and self-inflamed, Goodman is a public figure who, as he likes to say, “comes across,” a knight of the conference table, a pipe-smoking, problem-solving ideologue in the war of the pamphlets. Also a poet, no doubt here and there a crude one, no doubt nowadays even appearing a little addled, but still in God’s grace because he believes he has God’s message, a Jonah addressing Nineveh on the Hudson:

I have among the Americans

the gift of honest speech

that says how a thing is

—if I do not, who will do it….

In place of shining armor Goodman offers shining proposals, scribbles letters to the Times, lectures from campus to campus, scatters hectoring (if no less helpful) epistles on every subject, on psychology and sociology, pornography and technology, urbanism and education, on sex and ethics and aesthetics. Not surprisingly, the envious suspect him of being the thinking man’s Max Lerner. “It is true that I don’t know much, but it is false that I write about many subjects. I have only one,” he says, “the human beings I know in their man-made scene.”

Although a utopian and a communitarian, Goodman, nevertheless, has always been smitten with heroic “being in the world,” promiscuous pursuits, above all with America, not Imperial America, but with what he calls, “our beautiful, libertarian, pluralist, and populist experiment.” Thus he has—and it is one of the shrewder things about him—a sixth sense, an animal sense, in knowing which compulsions are benign (he is neurotic, but rarely panicky; a bohemian with a bohemian’s righteous melancholy and rackety interests), and which bits of cultural bric-a-brac are for him. (Jean Genet is for him, not Beckett; Reich is for him rather than Freud: “The Function of the Orgasm is a classic almost by definition, from its title,” he announces typically.) And when remembering Jefferson, as he does often, it is not so much Jefferson the disciple of Locke (whose tolerance was terminable), but a Jefferson who says:

“Let Shays’ men go!

if you discourage mutiny and riot

what check is there on government?”

Like other utopians, like the obstreperous Rousseau who wrote of alienation and the “social contract,” but when speaking of the rewards of “self-expression” spoke from the heart (“Oh, if you want to be a wolf,” he told Boswell, “you must howl”), or like Kropotkin, turning from the noblesse oblige of the few to the noblesse oblige of the many, Goodman, I think, is a narcissist, an embattled one, a narcissist, moreover, with historical consciousness, who saves his sanity and his sense of self by looking outward rather than inward. Anxiety over identity becomes anxiety about the world, love of person becomes love of Man.

He is—again a utopian characteristic—an impresario unable to keep his spectacle without a cast of thousands: “I have a democratic faith. It’s a religion with me—that everybody is really able to take care of himself, to get on with people…. If it’s not so, I don’t want to hear of it.” Confessing to thoughts of abandonment and death, as happens frequently in Five Years, and marginally, though no less drastically, in the two collections of his poems—the latest, Hawkweed, was published in 1967—Goodman does so the better to concentrate on thoughts of Communitas and Eros.

Advertisement

His heroes are Coleridge and Wordsworth, Aristotle and Kant, Milton and William James, and a few shaggy dog saints of the anarchist movements—or reasonable facsimiles thereof. But Goodman is also a product of his own Horatio Alger days of “growing up,” and of the Hollywood and Broadway of three decades ago. Auras of such sentimental or populist phases rarely seem far from any of his formulations. “If we handle it right,” he remarks, “professors can make these students see that it is also the University of Newton and Darwin, Sophocles and Kant, and perhaps that there is even something to be said for Justice and Ethics with capital letters.” Here, I suppose, it is Father Flanagan, or Pat O’Brien instructing Jimmy Cagney on behalf of the Dead End Kids, just as, when making common cause with the discontent or assumptions of a later generation, all the while calling teenage students “stupid,” or chastising the cheeky performance of the Beats, he suggests Grandpa in You Can’t Take It With You, cuddling his duffers and dilettantes, but demanding a call to order now and then….

Of course Goodman is famously, you might say excessively, earnest. “To remain earnest,” he tells us, “is already a revolutionary act.” It is an earnestness that pervades not only the shameless sexual data (homosexual, but heterosexual as well, pari passu) in the poems, some of the fiction, and Five Years (revelations, incidentally, that tend to strike terror in the hearts of his critics, partly, no doubt, because they seem so incongruous when set side by side with his civic-minded concerns), but, more important, a quality that circumscribes his whole demeanor, his vocabulary of moral supplication, urgency, and cantankerousness.

Hubris and humility, poetry and social philosophy battle for possession of the soul of Paul Goodman, but less in the manner of Faust than in that of a debate before a meeting of Quakers: “A part of God’s plan is my wish, and it is at peril of losing everything that I would fail to keep both contestants in the field, I and the world.” So subjectively measuring what is to come and “what has been lost” (“I habitually drift onto an ideal tangent, not ignoring the hardships of the old system, but speaking up for ‘what has been lost’ “), sounding puissantly radical in one breath, and hortatory the next, Goodman more than is usual with writers makes your own feelings react to his feelings, and either they meet or do not. In Five Years, he refers to himself as a humanist, a “Renaissance freelance,” and the term, though abrupt and self-regarding, is nevertheless apt: like his spiraling projects, prescriptions, and enthusiasms, so his emotions—never saying no to an impulse (it is, I suspect, more a matter of principle than of temperament), Goodman does not delay, he strides forth, gallantly picks up (all that “cruising”), stumbles along; rejected, he stoically awaits a new turn at the helm, one more chance.

When the energy slips out of gear, when the Aristotelian largess becomes pinched, when “the relations among the ego, the soul, and the world that can lead to happiness” do not, the spirit, rebuffed, grows insular, bookish. Then the writing, no longer trusting to the traditional themes of order and disorder, doings and undoings, runs to a sad stretch of spluttering and indignation, saved only, usually, from a sort of flag-waving paranoia by the buoyant dottiness of the language:

—now for this General Motors Corporation

that makes my town unlivable, and this

Federal Bureau of Investigation

that makes my country coward! oh today

I’ll bring low these insolent giraffes!

The enormous hunger characterizing Goodman’s work, a hunger for the “manly” covenant, a hunger for acceptance, change, justice, perhaps for what Irving Howe cheerlessly calls “asphyxiating righteousness,” is one, certainly, with the stormy simplicity of his proposals. Often Goodman seems incapable of surveying the world without coming up with a salvaging motto. So in his world you are “always in there pitching, although in a confused game,” and if you want illumination, if you want, as Goodman does, to crack the granite of middle-class complacency, a “question to ask is: who are your Jews, Queers, and Niggers?” Nor need that be dismaying, for “the minority is always a repressed part of the majority,” and “it is moral and psychological wisdom for the majority to accept the repressed part of itself.” Admiring the “conflictful community,” Goodman extols it not so much as if he had never heard of Locke’s “ill-affected and factious men,” but as if such factiousness were in itself a cathartic boon. The conflict between the middle class and the lower class, “in Levittown, for example,” “is not an obstacle to community, but a golden opportunity, if the give-and-take can continue, if contact can be maintained.”

Advertisement

Intimacy really means everything to him. Placing the sharpest value on the spontaneous utterance, the thing to be said, the thing to get out, yet schooled, helter-skelter, in the classical tradition, Goodman, predictably, is a glorious mixer. Politically, he blends, I think, Kantian morality with Humean expediency; personally, he “publishes thirty books and rears three children,” and indulges his idiosyncrasies. If Hebraic truth is prophetic and for the race, and Christian truth confessional and individual, Goodman irresistibly responds to both. In the novels, whether the naturalism of Making Do or the surrealist tinting of The Empire City, his heroes, devastatingly impressionable, keep fingering the chinks in the armor, the holes in the fences, wrestling with those parts of the economy, or the self, unexplored or unwanted. They are, like Goodman, both pariahs and charioteers.

Similarly, the poems. These are rallying songs of innocence and experience—querulous, anecdotal, prayerful, salacious. Often they are hymns to overcoming that which cramps, celebrating that which heightens, or brings together: “Creator Spirit, come.” The best, it seems to me, are unpruned or unornamental, zesty and life-giving, if only for the moment. The worst (and, happily, that means the minority) lack everything—fullness of language, flow of images—that poetry must be if it is not to be cactus.

Endlessly attentive to solutions for America, and salvation for himself, both an “anarchist patriot” and an “anarchist pacifist,” from book to book we see that Goodman is always struggling to become totally absorbed (“Total absorption in a limited attitude annihilates the sense of limits, and this is Nirvana”) or totally aware, to be “useful,” to “serve.” Thus he can be tendentiously lyrical over opportunities missed, and it is always the “second encounter,” which rarely arrives, that Goodman so hugely mourns. It is the second encounter which “could make a difference…in the repeat the ego-defenses are involved, a friendship could be formed, a feeling become a poem.” Built to stand his own ground, stand loneliness, intellectually at least, Goodman yet yearns for touch, contact, clasped hands, tokens of involvement, empathy, love. He makes love, sometimes prudently, sometimes disastrously, not only to assuage the flesh (or even), but more to instruct, to demonstrate that relations are possible, still. (On students, approvingly: “They seem to want the University to declare for the sexual revolution.”)

The quixotism, the peculiar pathos of Goodman’s career, comes, no doubt, from the drama of his public and private selves aching to interact—if not, a rashness sets in, or guilt. Thus it may be that Goodman’s utopianism is, in part, defensive: “Self-pity and utopianism are disesteemed among us.” Certainly you have the feeling (not always, but often enough) that the melting pot utopia, the “mixed system” he presents so persuasively in Communitas or People or Personnel or The New Reformation,* a system with classes in “eurhythmics” working on “incipient neurosis by unblocking emotion through muscular release,” a system with communist sectors as well as a market economy, is really psychotherapy conducted by other means, the continuation of a generously appetitive, marvelously many-sided, yet no doubt rather unhappy, ego through other channels. In the world, people are forever failing themselves and each other, and God is born—or utopian hope. Most dreams of Erewhon, surely, are dreams of getting the better of nature, of “fate”: they are revenge-fantasies in noble or disinterested disguise:

Impatiently I listen for the knock

that didn’t happen fifty years ago

and devise for the advantage of you all

vengeful reforms, some of them practical….

Fundamentally, Goodman is apolitical. That’s why his relationship to the left or the right has always resembled that of the Vicar Savoyard’s relationship to the Church: both are unorthodox and both have as little to do as possible with dogma as such—the attachment, rather, is emotional or ethical. Trust, loyalty, promises, bonds, making do—these are Goodman’s touchstones, and they are conservative values. And yet, for Goodman, contradictions are sweet, “Chaos is Order,” and confusions are blessed. “Confusion is the state of promise, the fertile void where surprise is possible again…. If young people are not floundering these days, they are not following the Way.”

Temperamentally, he has been as much at odds with the old guard’s monotonous intransigence, or with the neo-Benthamites of Madison Avenue, as he has been with the “up yours” rhetoric of the campus revolutionary. Yet he has always sought to preserve both the individual will and the general will, the saving remnant and the “ongoing human adventure,” -sought to “preserve and extend.” He quarrels with State capitalism and State communism, and always over the problem of proportion, and beyond that, of liberty: the insistence on ownership and the means of production, or on supply and demand, misses the problem of scale—if the scale is too large it ruins the matter, it centralizes and creates constraints. The best of culture, he tells us, always took place in the city-states. Thus his famous odes to decentralization, to breaking down the barriers between people and things, to demythicizing forms and institutions, to winnowing bureaucracies, showing us that these are merely aggregates of human defenses, complexes, retreats to unreason. He is a populist, but his populist dreams have suffered crushing blows: the “slum kids” and the union workers of the Thirties became the “fascist majority” of the suburbs; the flower children, the students of the Free Speech Movement appear, more and more, scruffy and bombastic: “It seems clear by now that the noisy youth subculture is not only not grown-up, which is all to the good, but prevents ever being grown-up.”

So he has been alternately exhausted and replenished, and all his works can be seen as determinedly honest, if impetuous, attempts at self-examination and self-fulfillment. That Paul Goodman became popular at all as a social commentator in America, where, more often than not, a social commentator becomes popular not because he “tells it like it is,” but because, as a woman remarked enthusiastically of Wallace, “he says the things we want to hear,” seems to me as much a cause for irony as for joy. His is thought to be a typical voice of the Sixties, and of course it is, and yet, when we look over his career, how untypical he sounds. He has never been seduced by the purely poignant, to which James Baldwin succumbed, nor has he ever engaged in a shouting match with History, as have Norman Mailer and so many others. The apocalyptic neither surrounds nor impresses him, and if, at certain moments, in certain ways, he has been preposterously humorless or perverse, fantasy-mongering or exhibitionistic, he has been saved, ultimately, by his character and his common sense.

He is an improvisational thinker, not a systematic one; inspirational effluvium bubbles from his pen. His reformist sympathies go awry, I think, in The New Reformation, where he pictures a new protestantism, made up of “earnest professionals” and conscience-stricken scientists, overthrowing the powers that be, forgetting that it was the old protestantism, the Calvinist ethic, which, in part, certainly, brought us to where we are now. Yet how resoundingly right so many of his social or economic or political recommendations seem, and how grateful America should be to him for them.

When I think of Goodman, I think of Wordsworth, his favorite poet, of the “principle of growth” and the bending spirit, of the wayfarer; and I think of Kafka, about whom he has written so densely and plaintively in Kafka’s Prayer, of Kafka saying of himself that “he lived without development, young to the end of his days,” Kafka always feeling in the wrong before God and man. These figures, I suspect, are somewhere present in all of Goodman’s works, and most especially perhaps in the following passage from Five Years, a flawed book, but the indispensable self-portrait, where we see how well, and how redemptively, Goodman has been wrestling with himself and his dilemma:

Deceived by his own wishes, in his private log Columbus systematically overestimated the day’s run. But he kept a false log to deceive the crew, to make them think that they had not come so far from land, and this “false” estimate was in fact much nearer the truth. His truth-for-the-people was his real thought; for himself he whistled in the dark.

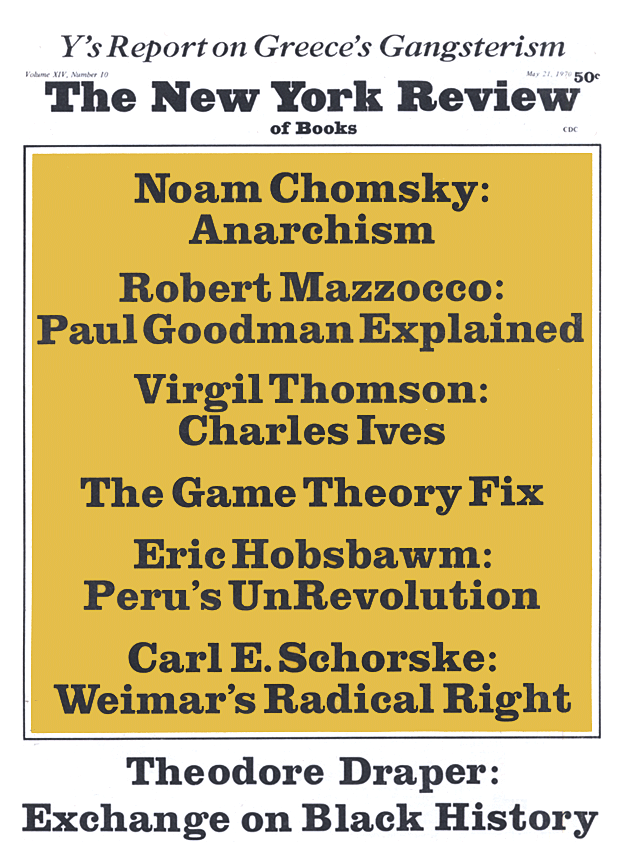

This Issue

May 21, 1970

-

*

Just published by Random House, 208 pp., $5.95. Two chapters have appeared in NYR (Nov. 20, 1969, and March 26, 1970). ↩