Italian novelists—who are they? We don’t find on the peninsula an impressive list to recite, like Flaubert-Balzac-Stendhal-Zola-Proust in the neighbor culture. With some scraping and hauling, we are likely to think of Manzoni, Verga, Svevo, D’Annunzio doubtfully, Fogazzaro perhaps, Pavese, Moravia maybe—it is not a long tradition, and though rich in various ways, it isn’t compact and sequential as various other national traditions obviously are. Carlo Emilio Gadda will certainly be found on future lists—affirming, as each of these novelists does, an extraordinary measure of global independence, a fresh imaginative start, stylistic riches—as well as a thin thread of typically Italian feeling which, though hard to define, is easy to sense.

Gadda is the author of two novels: the second written was the first translated. Quer Pasticciaccio Brutto de Via Merulana (published in Italy in 1957, translated by William Weaver as That Awful Mess on Via Merulana, Braziller, 1965) is, or pretends to be, a Roman detective story. It is written in a pasticciaccio or pastiche of different idioms, primarily the Roman urban dialect, seasoned here and there with some Spanish, Venetian, Greek, French, Milanese, Latin, and gibberish expressions. The central incident, though it starts as a normally nasty homicide on an average grubby street in central Rome, gradually spreads and deepens as Officer Francesco Ingravallo (otherwise Don Ciccio) investigates it. Like a livid stain it spreads—not just the crime itself, or specific responsibility for it, but the squalor and selfishness and pretension of Roman society in early Fascist days, of which the crime is just one random outcome.

We learn to suspect the pretty-boy cousin, the bullock husband, the terrorized, senile tenant, the scabby gangs—and always in the background is heard, or overheard, a thudding drumfire of imperial rhetoric. Language itself seems to break down and decay under the impulse of Gadda’s disgust; the regime is, every so often, reduced to a series of obscene puns on imperial terminologies, foul pomposities. There is no running down of the criminal, no triumphant elucidation, no arrest, no punishment; when the guilt has been sufficiently spread, sufficiently realized, in the midst of one more interminable interrogation, the novel simply stops. It comes to a breakdown, not a proper conclusion; repeating the pattern set by La Cognizione del dolore, Gadda’s first novel, which is only now being translated (again by Mr. Weaver) and published (again by Braziller) as Acquainted with Grief.

This novel was written and partly published (in serial form) more than thirty years ago, just before World War II. It broke off, once again, in the midst of an action, at a moment when the author had touched, so it seemed, an instant of unendurable agony. The present version contains a new chapter, taken from the author’s journals but not reworked by him, carrying the story a little further, but not to any proper conclusion. Gadda is now nearly eighty, and it does not seem likely that he will ever conclude either of his two novels or publish another. There is, in the background and as yet untranslated, a good deal from the workshop—journals, essays, sketches, several collections of stories (many of them fragments of still other incomplete novels); and of course there may be further revelations. Anything is possible. But the two fractional-novels we now have will probably always be the central pillars of Gadda’s reputation.

The setting of Gadda’s new-old novel is ostensibly South America, its time just after the 1924 truce between those traditional, interminable enemies Maradagàl and Parapagàl. There are some mountains, which could be the Andes; there is a feeling of jungle; there are peons or peasants, who could be Indian or mestizo, and in any case fall easily into garbled Spanish. And yet everywhere this South America is haunted as by a bad odor of Italy. This provincial capital, backed up against the immense cordillera, with the vast sloping plain in front of it—they call it Pastrufazio, which sounds strangely like “pasta fazool,” and it could very well be Milan. The Serruchón mountains are said to resemble closely Manzoni’s Resegone hills; the village of Lukones, if it were somewhere else. could be Gadda’s boyhood village of Longone. The smelly cheese which the countryfolk appreciate so liberally, croconsuelo, has many characteristics of Gorgonzola; the national grain, banzavóis, sounds like a sardonic echo of “pancia vuota” in Italian.

There are certain Nistitúos de vigilancia, staffed primarily by war veterans; the protection they provide (in return for a very modest fee) is of course completely optional, but those who don’t subscribe to it often feel that they should have. These are the Fascists and their victims. At the center of the scene and the book is a villa, where live the widow Pirobuttiro perpetually grieving for her elder son killed in the late war, and her embittered younger son, Don Gonzalo. These are said to be Gadda’s mother and Gadda himself.

Advertisement

Our approach to this tightly knotted domestic tragedy (so reminiscent of some of Pirandello’s) is gradual and casual. Gadda is a master of the elaborate, roundabout, unnecessary explanation that wanders through every conceivable back alley of irrelevancy. Of course, in a strange country like Maradagàl, there’s a great deal to explain. So we get quite a lot about the great national poet Carlos Caçoncellos, singer of the exploits of the Maradagalese cycle of the libertador (the libertador was General Pastrufazio himself), as well as about various villas (named enchantingly Giuseppina, Enrichetta, and Antonietta) and their lightning rods.

At first we wander cheerfully through this mildly ridiculous landscape, in the presence of our surpassingly articulate guide, under whose agile tongue landscapes and populations blossom, stories about gigantic lightning bolts pour forth, and this slightly askew South America is exaggerated to mythic proportions. There is always, to be sure, something nasty and brutish about life in Maradagàl, which usually reveals itself only gradually, as a result of our looking a little below the surface. It seems to be a rule of Gadda’s universe that the first thing we learn about any event is pleasant but untrue, the second thing we learn is much more disagreeable but probably not true either, and only the third thing, which is practically intolerable, has any chance at all of being partially true—mostly because nobody can endure the thought of looking further.

Since we start far outside the Pirobuttiro family, and approach it through the fussy peregrinations of the local doctor, a full quarter of the book has passed before we so much as meet the central character, Don Gonzalo. Though the younger son, he is actually by now middle-aged—a pedantic, longwinded, hypochondriacal celibate with a vague post in the civil service, a stubborn addiction to reading the philosophers, and a nagging discontent with the world. The doctor has come to investigate some sort of digestive trouble, evidently groundless; what he encounters is a classic complaint—a long, querulous catalogue of woes about the village, the government, the peasantry, and particularly Don Gonzalo’s now aged mother.

Overwhelmed by the death of her eldest son in the late war, she has withdrawn to a private life of agonized grief tempered by compulsive public charity, a mania (according to Don Gonzalo) of giving. She insists upon keeping the villa, living up to the estate, remaining in touch with “her peasants”; her son insists this is excessive, idiotic. The taxes, the supertaxes, the other taxes, the servants, the repairs, the insurance, the useless expenditures on every forlorn misfit in the neighborhood—they are lunacy, madness. Behind all these complaints of Don Gonzalo, an immemorial jealousy makes itself felt, an open sore of resentment against the dead brother who has monopolized all the love in the world. Evidently the poor doctor has been plunged into a pit of longfestering feelings and domestic recriminations. And, as befits a Gadda character, he proceeds to lighten the atmosphere by telling the amusing story of the deaf night watchman and his miraculous cure. This story provides an epitome of Gadda’s world.

Palumbo Mahagones (who was also known as Pedro Mahagones, Pedro Manganones, Pietrucchio, or even Gaetano Palumbo) had been deafened by the explosion of a grenade at Hill 131 in the course of the late national struggle; and would therefore be eligible for a government pension of the sixth degree, fifth category—or perhaps the ninth. But Colonel di Pascuale wasn’t altogether convinced that the disability was genuine; and so rigged a series of ingenious tests for the claimant, involving sudden questions, unexpected explosions, soft-voiced enticing females.

All in vain; he was deaf as a post. His anxiety was increased by involvement with an impatient widow in his native village—she wanted to marry him, but didn’t want to wait forever. The colonel ordered him held for two more months of observation; he sweated them out. His papers were finally prepared for a month’s terminal leave; at the last minute, as they were presented, he was told that they were for two weeks—and, in the presence of witnesses, he heard, he understood, he was cured. The passage concludes in a sanctimonious lather of eulogy to the colonel, whose devotion to duty was so firm, so noble, so selfless:

Through this duty, it was asserted by many rumors, and all of them well founded, he had by now recovered for the revenue of Maradagàl several millions of pesos, after having patiently, laboriously extracted them, as you extract the marrow from the ossobuco with that special little harpoon spoon that looks like a dentist’s implement, he instead from the chain of little bones, or from other bones or sinews or kidneys or bladders of certain robust young men, with too great a tendency however (according to him) to award themselves a premature pension of the fourth degree. Or sixth, as the case might be. At their age!

It must be observed, furthermore, that the just severity of the law, excluding from benefit the nonpossessor of qualifications, and the firmness assumed by the decisive commission in applying this highly sound order to the case in point, had and have an ethical significance, and achieve a social result, which altogether transcend the value of the thing disputed. Those thirty or forty young men, in fact, instead of receiving from the Maradagalese government an advance subsidy for sloth and idleness, with the false motivation of having suffered the war in their own flesh—which turned out instead to be as perfumed and intact as that of the most flourishing idler, or, if afflicted, still injured and poxed by a war quite different from that with the hated Parapagàl—those young men, I was saying, were stimulated by their nonpension to reflect seriously on their own situation and to seek, I would say, a different and more worthy means of subsistence. The position of night guard in itself is, to begin with, an honorable and socially positive employment. Some others, then, among those vigorous aspiring pensioners, but in fact pension rejects, and Mahagones especially, tried something even better: cooperating with all the energy of their spirit toward the progress, indeed the growing development, of the firm organism of the lucky firms, which were instinctively prompt in taking advantage of their cooperation. Making himself, I am referring to Mahagones, not only guard, but also hawker, procurer of lightning contracts, and lightning-collector or one might say a la fourchette, for the same firm. And learning above all, in cases of emergency, even to write his own name. Cooperating in the best fashion in the success of the most disparate enterprises—whether in the inserting of little pink-colored slips, every night, in the holes of locks, Agostonian, or Giuseppinian or Teresottian, or in detaching more substantial and detailed slips, violet, baby blue, or pink, from a pad with stubs, or in detaching them, month after month, identical—though they were apt to represent, month after month, a modulated, rising income, that is with positive differential, if one may take the word from the mathematicians—that is, affected—this income, by propitious (however modulated) increment and leeward tide.

What justifies the length of the quotation is the extraordinary vaudeville of the prose—its genteel, explanatory elegance, its steadily growing self-entanglement, its ultimate incoherence. Gadda’s fictional speech has a colloquial, intimate quality that reaches back to Manzoni; but, as this passage suggests, it is capable of a wide range of mimetic variations, gestures of psychic activity. With rare exceptions, the dialect of Anglo-Saxon fiction these days is less flexible; it is at best unidirectional, far less tolerant of artifice. With Gadda we return to the grand tradition of expressive prose. It is restive and unpredictable writing: Don Gonzalo can burst into a furious denunciation of the personal pronouns as the lice of thought, or boil up an incredible phantasmagoria of oiled bourgeois stuffing themselves into infinity. And over and over again, a moment of shimmering rage, recurs the scene in which the son ground underfoot his father’s watch, and threw his father’s portrait on the floor to trample it.

Advertisement

Obviously Gadda is not afraid of big Proustian scenes or daunted by kaleidoscopic Joycean vocabulary; his themes are worked out in psychological depth as if creating character were still possible. In view of current fashion, his simple presence provides a strong argument for our remaining aware of traditions outside this immediate American provincial world of ours, whose limits too often go unquestioned.

But in the end, Gadda’s claim on our feelings goes far deeper than a matter of contrasting styles. He has felt evil, watched it grow within him. It is no part of a reviewer’s function to describe the hideous event (and still more hideous implications) that brings the novel to its cutoff point—only to say that in violating the ostensible principles of a completed action, Gadda has pointed up the classic economy of his book’s emotional and tonal structure. The economy of the book is as extraordinary as its depth of feeling. La Cognizione del dolore is a beautiful and terrifying novel, in the tradition of novels to which adjectives like that used to apply.

By contrast with that awful pasticciaccio, Mr. Weaver has had a relatively easy time with Gadda’s first novel. He is a translator of immense resource and fluency, who translates, miraculously, into authentic English prose. In the long passage quoted above, there are a few phrases where one wishes second thoughts had intervened. A guardia notturna isn’t a “night guard” in English, he’s a “night watchman”; especially with all those lightning rods and lightning bolts in the background, it’s misleading to call a procuratore ai contratti-lampo, ed esattore-lampo a “procurer of lightning cóntracts and lightning-collector”—lampo in this context is more like “instant.” And the final phrase of the paragraph, vento in poppa, would go better in some locution involving “tail wind” than as a “leeward tide.”

Still, these are trifles; whatever liberties he has taken with the small equations, Mr. Weaver has rendered brilliantly the large ones. For the sake of pedantic exactness, we had better record that the third section of the novel, translated here and described as “unpublished in Italian,” appears in the fourth (1970), edition of the novel published by Einaudi.

Now that Gadda has appeared in English, we will, I think, be hearing about him for years to come. The weight and balance of his two novels will not be forgotten in one season, or two.

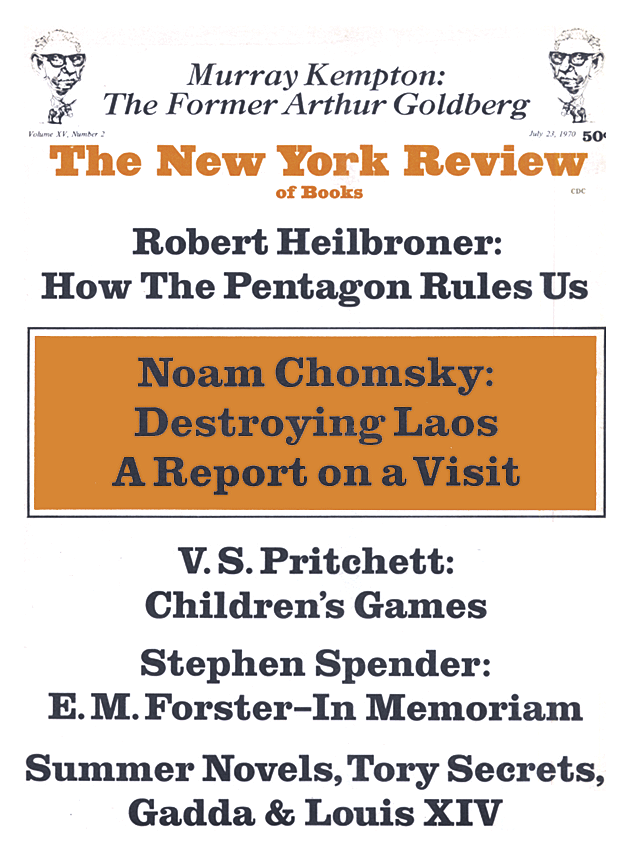

This Issue

July 23, 1970