In one of Richard Stern’s seven tales which, with two essays, make up 1968, there is a man called McCoshan, “a gentleman out of sympathy with the times,” who drops ideas, large generalizations, at breakfast-time, when he “uncovers for his wife the terrible configurations beneath the newspaper facts.” This is surely what Stern himself is trying to do, in what he calls “a diverse collection commenting on contemporary life.” So are the other two American novelists under review. They trade in social problems—those newspaper constructs which travel the media of the Western world, winning votes for conservative politicians, things like Student Unrest, Law and Order, the Color Problem, Pollution, Sexual Permissiveness, the Death of God.

The three authors take what may be considered a “liberal” line on such issues, but are not making much of a case. How could they? To make a case, it is necessary to produce evidence, a consistent narrative of plausible events with causal explanations. But these authors are too proud to adopt such a technique, however suitable it may be for the courtroom, for reporting, for history books or the anecdotes of conversation. We are expected to agree that the novel has got beyond that stage; that there can be no realism, since there is no agreement about the nature of reality; that what people call the real world is only a fiction, an attempt to put in order something essentially disorderly; that true fiction must admit to telling lies, pointless lies, and discuss those lies in an amiable manner. The “newspaper facts” discussed by McCoshan will not be ordered and explained, and are beyond parody. These books are games, made tedious by conscientious moralizing and mimed profundity.

One of McCoshan’s moralizing propositions is that

…the Birchers, Minute Men, Neo-Nazis, and the NRA are far more useful than the planners, utopians, and think-tankers. Why? Because they take care of civil roughage. They’re the national excretory system.

A story could be built from this overambitious epigram, but not by Stern: he would rather write about people discussing public affairs, making large statements in a musing, self-congratulatory manner. Polyglottal sciolists all, they show and tell nothing in particular. We may remember Isaac Babel saying:

We have no one who knows how to show anything any more. They just talk about it, very long-windedly.

According to Stern’s publishers, his ambition is much like that of his own McCoshan: he wants to “wrench current dilemmas into patterns that clarify” and to “evoke the misery and comedy of the crucial year of mid-century America.” He has not succeeded His publishers are nearer the mark when they flaunt a review of his earlier work: “Enough to frighten a rustic.” Stern’s English is Butch Academic, allusive and exclusive, mingling a studied demotic with a little learning, none too lightly worn, so that each sentence seems designed to impress rather than communicate. Newspaper tragedies are made subjects for epigram; of more real concern are newspaper reviews, articles in the London Times Literary Supplement, or Mailer on masturbation:

“Why the author who strokes himself more publicly than any writer since Whitman should have this terrible bug about the most economical of pleasures, this old economist knoweth not.”

Dugan disliked such subjects, had to force hearty interest.

“When a man’s work is done to corral nookie, and Mailer must get plenty, he’s naturally going to crow over poor lugs like you beating their meat to Judy Collins. If he ate shit, he’d be knocking hamburgers.”

“It’s more complicated than that. The guy hates solipsism….”

This fairly lucid and amusing example of Stern’s writing comes from his tale, “Idylls of Dugan and Strunk.” But his donnish, nervously bawdy whimsicality and his desperate search for mots justes can become a strain, especially when he strays into the world of physical action and attempts to remain knowing.

Dugan is too busy to shift historic furniture. His quarry is very present-tense indeed…. “I’m not much on sarcophagi. I’m only at the Titus Andronicus stage of my life.”… A clot of teenagers looked across the iron-pillared, Elshadowed street. The horn yowled on. Dugan felt his old street-fighter’s click.

What is happening is that two university prosers—Strunk, the old economist who knoweth not, and Dugan, the one who forces hearty interest—have got involved in a street riot. The tale concludes with an uncontrolled, page-long, prose-poem-type sentence (which means “Pow!”) and finally leaves the prosers’ car “winging by glaring incarcerated eyes toward the light, toward the open green and light of the Midway, toward the gray university towers.”

If the author had allowed Dugan and Strunk to admit that they are very feeble and boring people, they might, I suppose, have proved as interesting as Beckett’s characters; but Dugan and Strunk seem to be thought worthy of respect and sympathy.

Advertisement

The same applies to the tedious musician, Wendt, hero of the novella, Veni, Vidi…Wendt, who offers musical examples composed for Richard Stern by his friend, Easley Blackwood. Wendt’s ruminations are stiff with capital letters, famous names put slickly in their place. On a single page we are told about Schoenberg, Lehar, Berg, Mann, Ravel, Stravinsky, Pound, Beethoven, Joyce, Giacometti, Michelangelo, Mozart, and Shakespeare, among others, and also “those elegant books of R. Craft.” Elsewhere, we are told of A. von webern, Dr. S. Johnson, and H. Morgenthau. But we are not told very much, despite R. Stern’s air of knowingness. The frightened rustics may excuse his breathlessness, assuming that new insights bubble up so fast in him that he cannot stop to develop them into argument or realize them as fiction. But, if that were so, he would not repeat himself so often.

We may allow that many good writers have revealed something of themselves by repeating their favorite jokes in different works. If we are dropping names in this chummy way, I have noticed that B. Jonson’s favorite joke is about people selling their farts; O. Wilde’s is about ugly old mothers; G. Byron’s is about women longing to be raped. R. Stern’s favorite joke is about Martin Luther King being a Jesus looking for a Judas, a joke which does not amuse me at all. He also twice quotes Tacitus’s joke, “capax imperii, nisi imperasset,” but does nothing with it, except to show it off. (It is a joke against the emperor Galba and means, roughly, “an emperor with a great future behind him.”) Stern’s Latin tags are overfamiliar to those who read Latin, annoying to those who cannot, and too inaccurately spelled to be helpful to the autodidact.

His English is not unlike that of Stanley Buchta (short for Butch Academic?), the narrator of Irvin Faust’s novel. Buchta himself refers to “that polysyllabic nonchalant style of bright college kids”—but not, unfortunately, in a spirit of self-criticism. Here again there is an effort to wrench current dilemmas into a pattern; and once again the result is a clotted language wrenched into knowing allusions and mots justes enough to frighten a rustic.

With a reciprocal nod at the stark one, I say “Hasta luego” and walk out…. I had a sudden déjà écouté off that sentence…. It is a wild ambiance out there in the streets. Very hard on the power structure and its muscle…. Ignatz the Mouse is now a hippie gorilla…. Taylor’s hands thonked behind his back. “Fuck you too,” he said…. “It is the condition of the ass-end of the stick,” he explained, “not to know it is the ass-end.” “Hot shit,” breathed Fritz.

The plot thickens; the clot thonks.

At first, The File on Stanley Patton Buchta reads like an attempt at a thriller for well-read university graduates. But as it dodges uneasily between subjective fantasy and objective reporting, between social comment and self-indulgence, between wiseacre knowingness and bewildered mystification, it begins to invite comparison with a picture-story I have just been sneering at in my small son’s comic book—a banal tale about conflict between a left-wing student group, the CTT (Citizens of Tomorrow Today), and some savage policemen. Among the students is the supernatural boy Robin (Goodfellow or Puck to Batman’s Oberon) and he has discovered that all the disorder is inspired and organized by “phony police working in cahoots with the CTT leaders to discredit the college and shut it down.” Robin overhears the supposed policemen saying: “With America’s universities closed, where do they get new brains to fight us, Comrade?” The nauseous CTT Yippies, who mislead decent students, are also enemy agents.

Robin beats them all up, then announces: “Cool it, fellow-students. When the real police check these bogus cops’ fingerprints, they’ll find out who’s really been running this show. And don’t take off on those misled ‘leaders.’ Their beefs may have been legit, but their tactics weren’t!” Robin, like all the other principal characters, is in disguise; but he assumes that somewhere there are real students and real policemen, sharing a common attitude toward law and order.

Faust’s novel contains similar incidents, but without the assumption that anyone or anything could be called real. Stanley Buchta is a New York policeman who has infiltrated a left-wing student group called the BUC (Believers Under the Constitution). He also joins a right-wing policemen’s conspiratorial cell, the Alamos—one of whom has devised a plan for stimulating a Negro-Jewish civil war in order to provoke a right-wing coup d’état. Buchta is a fine dancer, surfer, motorist, fighter, lover, connoisseur, and wit, falling somewhere between Batman and Philip Marlowe in credibility. He is also very good on the geography of New York City: street after street is listed, digit by digit. On top of all this power and knowingness, Buchta is a trusted intimate of a Black Power group called the Zulus, and is loved by black Darleen because she has a lust for strong handsome blond men.

Advertisement

A skilled police spy, a master of disguise, he ought to make a good narrator for a novelist who wants to display intimacy with the quarreling sects and subcultures of New York. But only an infant reader would want him to be Batman—or Superman. (We may remember the super-narrators in Faust’s book of stories, Roar Lion Roar.) The author does not seem to be indulging in parody heroics, winking at the reader, when he displays Buchta’s power and wisdom. “One of the kids swung at my groin and I sapped him. I chopped two others before I…started the slow flashing glide into blackness.” (Pow!)

We made it all the way through a merengue, with the floor thinning out, and I even tried a few tricky spins away from her…. Some idiot shagged into an open break and bumped her hard, but not before he got an elbow…. I spent forty minutes at the George Bruce library on 125th near Amsterdam flipping through 19th-century South Africa and then zig-zagged briskly up to Everett’s place…into what must have been the parlor when Harlem was Haarlem. It was very well (and unferociously) done in Swedish modern with Japanese prints.

This does not seem to be a satire on the cinema hero, but rather a straight-forward attempt to write a role for, say, Glenn Ford.

We feel that this detective ought to be unraveling some particular mystery, exposing some particular villains. But all he tells us about is the rhetoric of political sects. Manifestoes are two a penny: we can read all that in the underground press or even comic books. Protesting a new school called “Jefferson,” the left-wingers announce:

“Jefferson was Mr. Charley. This man whose name will mock you day and night as it gleams over the river, this Charley kept hundreds of slaves. That is historical fact, my friends. WHADAYOUSAY?”

“No school. I’m no tool. FUCK THOMAS JEFFERSON!”

Meanwhile the black protesters orate about long-dead Zulu kings:

“Warriors, you will find no statues of Shaka. No granite tombs. Hell, he doesn’t even rate with Mr. Bolivar who fought for the same thing, his country…. Abie Lin-Cohen did all he could to lose the war…. Abie Lin-Cohen, our greatest president! Shaka, a crazy savage!”

The right-wing policemen express with similar extravagance their hard-line Batman and Robin ideology:

“There are plenty of fine, decent young people in this country who know what a bar of soap is, who do not hate their parents’ guts, who in fact recognize that their fathers did a pretty good job, that they went out and fought the toughest war in history to save this country so all the yips and flips could burn their draft cards and spit on the flag. Remember the Alamo!”

Perhaps Faust is deliberately making a point against these three groups of crackpot rhetoricians, all obsessed with ancestors’ memorials. But there are pages of this stuff, and it is boring, merely the froth of politics. A real policeman could have told us what really happens to particular people in New York, but Buchta would rather report the speeches of mystagogues. The rest of his time is spent in driving speedily or striding purposefully around the City, displaying knowledge of streets, shops, and restaurants, wise-cracking toughly—like a professor imitating a cab driver and, somehow, getting it wrong. All this knowingness seems a disguise for bewilderment. The idiotic Batman and Robin tale did at least have a point, did make an attempt to tell “who’s really running this show.”

More tiresome is The Bamboo Bed, partly because the newspaper facts being used are those concerned with the Vietnam war. Like (probably) most people in the world, I regard this war as a defensive action by Vietnamese fighting-men against successive foreign invaders—Japanese, British, French, American. It is irritating to see it once again presented as, in William Eastlake’s words, an American “middle-class hang-up,” the conflict explicable in terms of Aggression, Role-playing, Immaturity, the Games People Play.

For much of the book, an American captain called Clancy lies dying in a jungle clearing, with images and archetypes in his head. He is often compared with Custer, and there are references to British history—Balaclava, Byron, Disraeli, Gordon of Khartoum. (The latter pair of archetypes, incidentally, also appear in Irvin Faust’s novel, together with Kitchener and the Zulu wars. The British reader wonders if this has anything to do with American intellectuals ambiguous feelings about WASP hegemony). Clancy wears a Roman helmet and is accompanied by a drummer boy and a French-Vietnamese mistress, Mme. Dieudonné—“never known for her shyness, never famous for modesty, tact, decorum, and all that passes for a lady even in Nam. You do not control the largest rubber plantation in Viet by games that women play.” We note the ponderous, repetitive knowingness characteristic of this kind of overeducated fantasy.

Floating above the jungle in a helicopter are Captain Knightbridge and a beautiful nurse lieutenant, making love, not war. They are known as Tarzan and Jane to their subordinates in the 379th Special Task Force Search and Rescue. These subordinates have given up fighting, and state that they are

…acting out their role as soldiers…. They felt like apes. They looked like apes. They took on the mentality of apes. They took on so much the mentality of apes that they no longer believed in killing, as men do, as men will, as men should. Oliver and Edgar no longer believed in war. They had become completely uncivilized. They no longer wanted to kill their own kind.

This passage is characteristic of William Eastlake’s use of Irony and Linguistic Recurrence.

The reiteration of such simplicities becomes maddening after a while, like a wet finger rubbed on glass. One paragraph begins: “A Vietnamese child found a helmet. With a helmet you can play war,” and the paragraph concludes with the same two sentences, and further down the page we get: “A child who found a dead helmet. A helmet of the dead”—so that the word arrangement suggests the work of a caption writer trying, at short notice, to compose something “poetic” and “poignant” to accompany a newspaper photograph. A mimic profundity is buried among these incantations:

Both sides play children. The peasants are not children. The Vietnamese peasant is a rice-paddy-working adult.

The female sex is also characterized as being adult and mature, as opposed to the men fighting for the United States or for the National Liberation Front—who are alleged to be playing Cowboys and Indians.

It is not clear to me why we should think of the NLF, or Viet Cong, as children playing Cowboys and Indians. The author introduces into his tale only one member of this force. A Chinese called Cho Lin, he is a Red Guard member who has been sent to Vietnam as a punishment for beating up too many people in China.

Clancy was saving the world from communism. Cho Lin was saving the world from capitalism. Clancy’s mother saved string, his father, old newspapers. Cho Lin’s mother and father saved cats that fell in the Wai Pe canal.

The whimsical complacency of this stuff is unnerving.

Among Babel’s remarks on writing, we may remember his statement that “all work consists in the overcoming of snags”; and that “you have to have strong fingers and whipcord nerves to be able to rip out of your drab prose, until it bleeds those bits you happen to like most but which are needed least.” These three novelists have preferred to accumulate their snags, to pile up surrealistic pictures (based on word-play, not the senses) and add moralizing captions, their banality disguised by tortured language and recondite allusion. Having chosen subjects of public concern for their material, they feel it their duty to pass acute judgments, instinct with wisdom and compassion, but they are too diffident to take sides in the conflicts they observe, and their lack of commitment makes their elaborate constructions seem all the more hollow and pretentious. Babel also said:

I don’t believe a writer’s heart and mind are more highly developed than other people’s. I think we are nearing a time when scholastic, artificial works, not imbued with feeling and sincerity, will be on their way out.

There is certainly no danger of their being accused of attempting to represent reality, to make the reader enter a world of make-believe, like a dream, and identify with the characters. No one will “get lost” in these stories or forget that the product in his hands is merely a verbal construct. Philippe Sollers is yet more insistent on this negative approach. But he makes his break with the traditional novel form in a very different way, and The Park, hollow though it may be, is very refreshing after three stuffy novels in which no one feels a thing—feels, that is, with the five senses. The narrator of The Park does nothing else, writes about nothing that he has not sensed:

I pick up a knife and give a light tap on the rim of the crystal glass that gives out a high-pitched note, or a lower-pitched one if I tap the glass farther down. I half fill it with wine, raise it to the light to look at the red liquid and drink some of it. A rich, perfumed, almost imperceptibly sharp taste. The presence, the weight of food and liquid in the mouth. White plate, white napkin, silver cutlery.

These are remembered perceptions. The only sure fact, the only concrete presence, is an orange exercise-book in which the narrator is writing while he perceives what is perceivable, remembers or imagines sights, sounds, smells, and tastes.

This slightly stooping body is my body and I can see part of it, wearing a blue woolen pullover…. My left hand placed flat on the page to stop the exercise-book from slipping. The skin, a little reddened by the light, the fingers, I can make this piece of modelling move as I wish.

Stern-like, I am tempted to gloss these passages with knowing references to Descartes and M. Proust; but why not just take them as they are? The author’s spirit is purely selfish. Nothing wise, compassionate, or educational is attempted. The only time moral language is used is in his description of people reading different newspapers in which the execution of some political prisoners is described, with different captions under the photographs, such as “Justice has been done” or “The rest is silence.” One caption—said to be “more favorably disposed to the victim”—asks, “What were his last thoughts?” Another caption runs: “Under complete self-control, he expressed the wish not to be blindfolded.” The narrator’s comment—“The man seems to be behaving in an exemplary fashion”—comes as a complete surprise, so that we feel inclined to congratulate the fictional caption writer for tempting our narrator into an expression of approval.

For the rest of the time, he tells of incidents involving a woman friend, a man friend, and a child. He remembers or imagines the woman as his lover, the man as being killed in a war, the child (and perhaps the man, too) as himself. Sheridan Smith’s prose adds a certain solemnity, a Latin dignity, full of words like amplitude, lassitude, and plenitude, ambiguous equivalences and infinitesimal transitions. This is partly because he likes to use the English word which sounds most like the French, however unidiomatic. When this translation of Sollers’s ten-year-old novel was first published in London, the Times Literary Supplement made game of Sheridan Smith for translating “la topographie d’anciens combats” as “the topography of ancient combats,” and there are many other locutions which sound more stately, more lapidary than the author perhaps intended. “Practising a diversity of callings” sounds more imposing than “working at different jobs”—and “contemplate” grander than “look at.”

Nevertheless this spare, disciplined, determinedly unpretentious novel is a mild pleasure to read, if you are surfeited with metaphor. Describing Santa Barbara seaside villas, Richard Stern called them “glassy monocles snooting it over a subdued sea”; but Sollers treats houses as houses. With no plot, no characters, no ethical attitudes, no causal connection, he offers nothing for a reviewer to judge, but merely an experience, an event, a refreshment. His book is partly about (French) language, but partly about sense perceptions and might have been more closely translated into cinema than into English. It is not exactly what most of us want from a novel, but worthy of respect for what it is.

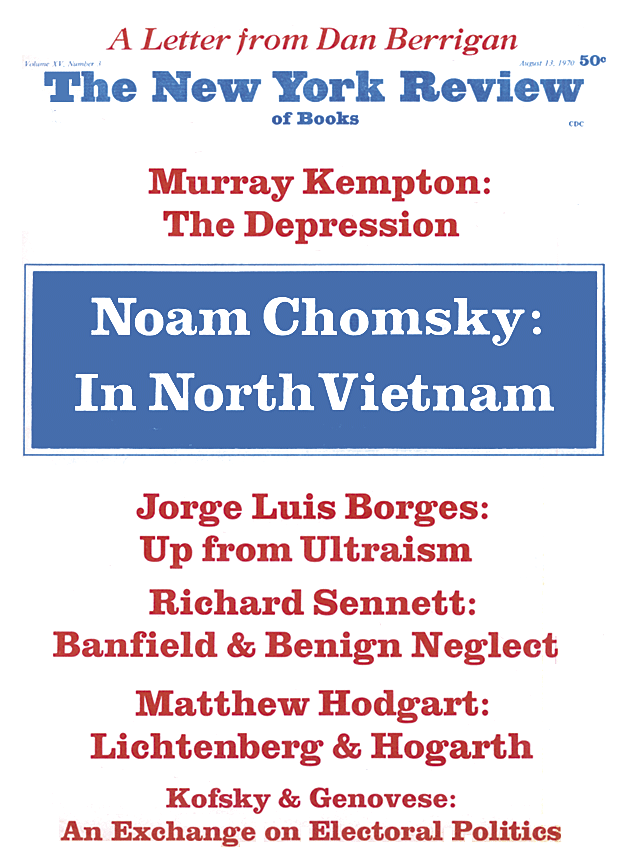

This Issue

August 13, 1970