In response to:

Mystic - Making from the July 2, 1970 issue

To the Editors:

Can Dr. Elwell-Sutton [NYR, July 2] be ignorant of the fact that Idries Shah’s father was an internationally celebrated scholar whose last appointment was representing Indian culture* in the whole of West Asia? To mention him at all in the review of Idries Shah’s The Way of the Sufi and Tales of the Dervishes may be irrelevant: but to mention him in such ill-informed terms seems extraordinary.

Does Dr. Elwell-Sutton not know that eminent scholars interest themselves in ancient MSS when they are produced, not when they are talked or written about? To mention Idries Shah’s brother’s version of Omar Khayyam without relevance to the books under review is perplexing enough; but that he concerns himself with trying to establish a negative about the MS is astonishing.

Dr. Elwell-Sutton’s lack of information, sheer facts, about the considerable literary achievements of Idries Shah and his wide acceptance among British and other critics seems to me little short of amazing.

Is it possible that he does not know that Shah’s “scribblings” (The Way of the Sufi) was chosen nearly two years ago on the important BBC “The Critics” program as an Outstanding Book of the Year? And, if he does, does this mean that the work of some 20,000 other British authors is less than scribbling? Did he not hear that Shah’s Reflections was also thus chosen?

Are we to assume that Dr. Elwell-Sutton reproaches Sussex University’s School of European Studies for inviting the author of a “schoolboy essay” to address members of the University? The essay in question, soberly enough entitled Special Problems in the Study of Sufi Ideas, rapidly sold out, largely to students and scholars, two editions with no publicity. Does Dr. Elwell-Sutton take issue with the eminent orientalist Professor James Kritzeck, on Tales of the Dervishes, that it is “beautifully translated”? And a host of other critics?

In a recent radio broadcast on Britain’s cultural frequency, BBC-4, one academic, a television personality, a scientist, and one of our foremost literary critics agreed that Shah’s work was of outstanding worth, praising it for its style, content and significance for our time.

Could it be that The Times Literary Supplement, the Educational Supplement, The Spectator, Time & Tide, New Statesman, Sunday Times, Sunday Telegraph and the Observer are all cultish devotees of Idries Shah, that they so regularly and seriously welcome his work?

Dr. Elwell-Sutton may not have heard, but very numerous literary authorities praise and use his work without having—although sometimes in daily contact with Shah—any inkling of the metaphysical pretensions seemingly imagined by the worthy Doctor. Richard Attenborough featured his travel book on television and it was chosen by the Travel Book Club. Dr. Louis Marin hailed his anthropological text Oriental Magic as an important work—and he is head of the Paris School of Anthropology. How is it that such distinguished and, we suppose, qualified individuals as Geoffrey Grigson, Isabel Quigley, Ted Hughes, Pat Williams, Desmond Morris and a host of others write such thoughtful and complimentary pieces about Shah?

Dr. Elwell-Sutton evidently has too little information, and it is too late. Shah’s reputation is extensive and impressive, at least in this country. His work, said to be based on 1,000 years of Sufi writings, is everywhere considered remarkable. If it is, rather (as Dr. Elwell-Sutton seems to want us to believe) of his own concoction, then Shah is an astounding genius.

Shah’s latest book (The Dermis Probe) was chosen as an outstanding Film of the Year and selected for showing at both the London and New York Film Festivals. He has just been featured in a full-length documentary film about himself and his work in a series devoted to eminent men of the time.

In short, Dr. Elwell-Sutton’s piece might almost have been written by a P.R. man acting for Shah, in order to elicit such a reply as this, listing a staggering record of appreciation and significance over the past fourteen years, which has rarely been surpassed.

Ignorance, I will admit, is no crime, and I am sure that Dr. Elwell-Sutton does not claim to be a literary man. But motivation has its mysteries. Dr. Elwell-Sutton may not indulge in imagination and innuendo, but it seems that his informants do. As a scholar, and a respected one, it can surely do him no good to rely upon this kind of material.

Doris Lessing

London

L.P Elwell-Sutton replies:

I am sorry that my absence abroad should have prevented me from seeing earlier the comments by Idries Shah and Doris Lessing on my review of the former’s books. Not that there is very much to be said in reply. Idries Shah, as usual, reveals his singular unoriginality of mind by failing even to produce a retort of his own, falling back instead on the warmed-up (and misquoted) wit of another. Doris Lessing’s diatribe, though longer, is equally bankrupt of ideas. What she describes as “facts” are of course merely the reported opinions of others, and their worth is proportionate to the qualifications of their owners to speak on the subject under discussion. It will not have escaped the notice of your readers that the list of those who have praised her hero’s work contains at most one with any knowledge of Islamic literature, religion, and philosophy. They are in fact for the most part the people who, with Robert Graves and Doris Lessing, were taken in by Omar Ali Shah’s “manuscript” of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam—and that, by the way, is why it is relevant to mention it in the context of a review of his brother’s writing.

I am grateful for Doris Lessing’s advice on the subject of ancient manuscripts. I would be delighted to examine Omar Ali Shah’s document; but since, nearly four years after the announcement of its discovery, he has still failed to produce it, or even any details of it, that pleasure has been denied me. Omar Ali Shah’s dilatoriness is indeed understandable; careful analysis of the evidence in the Graves/Shah book long ago convinced me (and many others) of the imaginary nature of the “manuscript,” and he knows very well that he cannot produce anything good enough to convince the experts—though if it would be of any help to him, I can give him the address of an excellent forger in Teheran.

I wish that, when I was writing my article, I had been able to include a notice of Idries Shah’s latest publication, The Book of the Book. Of this it could scarcely have been said that it was not worth the paper it was printed on. Out of nearly 200 pages only nine carry any print at all; the rest are blank. But I suppose his admirers among the Hampstead intelligentsia will have swallowed this buffoonery with the same enthusiasm with which they have gulped down the rest. It’s all very odd. I am disinclined to credit the Shah brothers with hypnotic powers—though anyone who listened, as I did, to the BBC radio program referred to by Doris Lessing might have been forgiven for suspecting something of the kind; I am still amused and amazed when I recall the sycophantic manner of Idries Shah’s interlocutors.

But I imagine that the explanation is rather simpler. Some Western intellectuals are so desperate to find answers to the questions that baffle them, that, confronted with wisdom from “the mysterious East,” they abandon their critical faculties and submit to brainwashing of the crudest kind. In fact there is nothing particularly mysterious about the East; but to gain some understanding of and familiarity with its thought does require a good deal of hard work, and that naturally does not appeal to dilettante mystics like Doris Lessing and Idries Shah.

One final word: I am not a Doctor (a “fact” that Doris Lessing might have verified for herself); but I have spent nearly forty years studying and teaching the languages, literatures, and cultures of the Middle East. Unlike Doris Lessing, I do not rely on informants; I prefer to find out for myself.

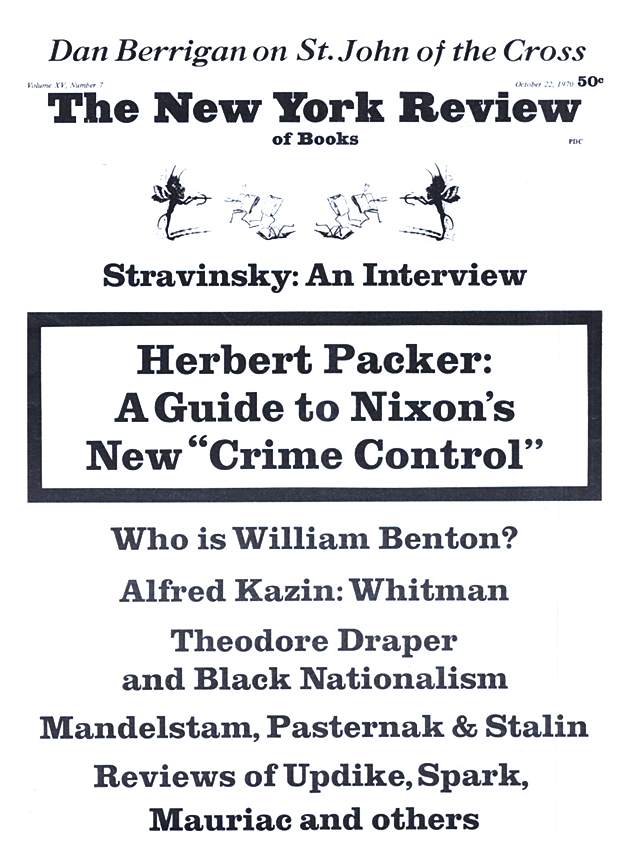

This Issue

October 22, 1970

-

*

The Indian Institute for Cultural Relations. ↩