To the Editors:

Dr. Donald Gatch of Bluffton, South Carolina, has attracted national attention over the past few years as the “Hunger Doctor.” He first came to prominence in the fall of 1967 when he testified before the Citizens’ Board of Inquiry into Hunger and Malnutrition at a session in Columbia, South Carolina. Based on his ten years’ experience as a general practitioner, Gatch told of the widespread existence of chronic malnutrition, vitamin deficiency diseases such as scurvy, rickets and pellagra, and intestinal parasites—hookworm, roundworm and whipworm—which he said were responsible for at least eight deaths in the area.

He complained of discriminatory medical practices against poor and black people: “Well, just a typical example, a mother brought a nine-year-old girl to my office Monday. She apparently had had a ruptured appendix since Friday. We took her into the operating room. Again, I kinda snuck her in because it’s against the rules to admit a patient without money. And when we got her on the surgical table one of the surgeons said, without any comment especially, ‘This child has rickets.’ And when we got in the abdomen and were doing the appendectomy we found some roundworms. And he said, ‘Of course, in these colored children the closer we get up the ilium in the stomach the more worms we will find because these kids don’t have much to eat.’ And this is where they head, they get the food before the kids do, and whether the kid will live or not, I don’t know. The mother didn’t want to bring the kid to the doctor because she didn’t have any money.”

He also related his attempts to get money to work on the health problems of the poor: “I tried to get an NIW grant to do something about it, and it had to be funded through a university, and universities aren’t especially interested in this. I called the Rockefeller Foundation and got a very—well, their response was that they weren’t interested in problems of America, the American health problems were being dealt with by the government, and they were doing it in foreign countries now. I approached the county health department initially about it and they said this is a problem that had been with the people since time immemorial and until the colored people got educated enough to wash their hands that there wasn’t any point in treating them.”

Gatch returned from the hunger hearings to find himself the most unpopular man in, that part of the state. Every other doctor in the county—all of them white, and all of them maintaining segregated waiting rooms in their offices—signed a statement denying Gatch’s charges. His white patients left him and his rent was doubled, so he was forced to close his office in Beaufort, losing with it his staff privileges at the local hospital. The Beaufort Gazette lashed out at him editorially: “Dr. Donald E. Gatch has done Beaufort County a great disservice. We suggest that he stop running his mouth and use his talents to alleviate rather than aggravate.”

The effort to quiet Gatch, discredit him, or put him out of business was not limited to the local area. Governor Robert McNair and other state officials were concerned about the effect that the publicity about hunger would have on the tourist trade and the state’s efforts to attract outside industry. According to Senator Ernest Hollings, “You don’t catch industry with worms—maybe fish, but not industry.” Mississippi Congressman Jamie Whitten, who controls the appropriations for the Department of Agriculture, had Gatch investigated by the FBI.

The most serious attempt to end Gatch’s practice began last November when the Beaufort County Grand Jury indicted him for four violations of the state drug laws. Conviction could have brought up to six and a half years in prison and a fine of $6,500. Gatch denied the charges, saying: “The state of South Carolina has been trying to discredit me for the last two years. I view this indictment as being politically motivated and another attempt along this line.” He said that he had been “told last summer that if I would leave the state there wouldn’t be any prosecution.”

When the case came to trial on August 10, 1970, the state dropped the three most serious charges, and Gatch pleaded guilty to the minor charge of failure to keep adequate records. Since he became a national figure he has been inundated with mail from around the country and, lacking regular secretarial help, all of his paperwork got months and months behind. The judge gave him the maximum charge of $500 fine. But that did not end the case.

The transcript of the trial has been forwarded to the State Board of Medical Examiners to decide whether or not Gatch’s license to practice should be suspended or revoked. It is ironic that a man who has come to be a symbol of social responsibility in the practice of medicine should now face loss of license on such a minor charge. But Gatch has always voiced his criticism of those doctors who specialize in “the diseases of the rich,” and this has not increased his popularity in the profession, at least in South Carolina. Now that a group of doctors will stand in judgment of him, Gatch’s supporters are fearful lest prejudice rather than the facts at hand be the determining factor in the case.

What You Can Do To Help:

1.) Write to the State Board of Medical Examiners, 1707 Marion Street, Columbia, South Carolina. Urge them not to suspend or revoke Dr. Gatch’s license to practice medicine.

2.) Write to Governor Robert McNair, State Capitol, Columbia, South Carolina. Governor McNair appoints the members of the State Board of Medical Examiners. Urge him to use his influence to see that nothing happens to Dr. Gatch. Remind him that people across the country are watching the outcome of this case, and that it will influence their view of the quality of justice in South Carolina.

3.)Write to Senator Ernest F. Hollings, United States Senate, Washington, D.C. Hollings made headlines last year when he admitted to the McGovern Committee that “there is hunger in South Carolina. There is substantial hunger. I have seen it with my own eyes.” But, as a practicing politician, he has always kept at arms length from Dr. Gatch. Urge Senator Hollings to use his influence now to see that Dr. Gatch does not lose his license.

David Nolan

Ten Penn Community Services, Inc.

Box A

Frogmore, S.C. 29920

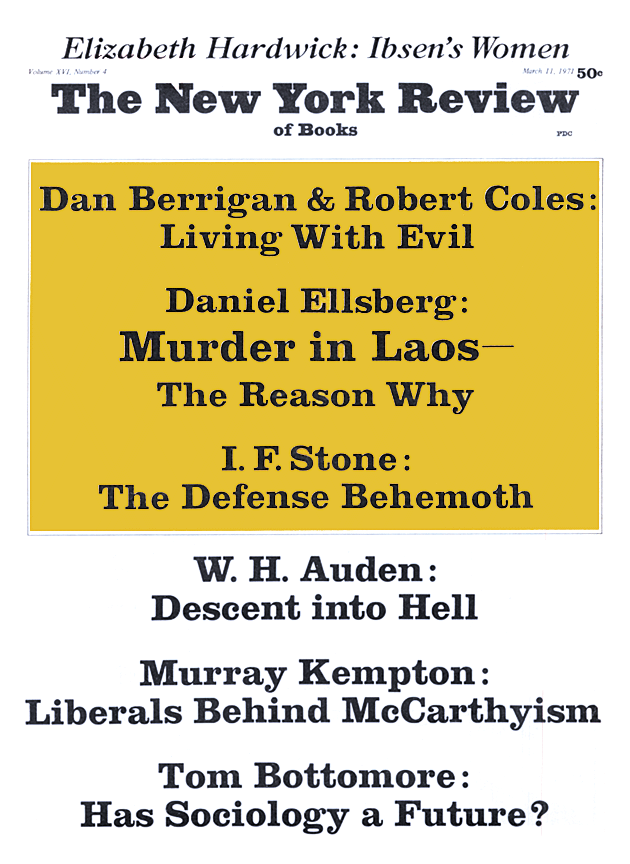

This Issue

March 11, 1971