Several years ago, Robert Penn Warren offered a recollection of his short story “Blackberry Winter,” describing how he wrote it and what he had hoped to do. It was, among his stories, almost a work of pure imagination, certainly not a transcription of fact. Of his characters in the story Mr. Warren said, “I never knew these particular people, only that world and people like them.” But he remarked of his novels that they started “from some objective situation or episode, observed or read about, something that caught my eye and imagination so that feeling and interpretation began to flow in.” He did not say anything further about the relation between episode and feeling.

I suppose the writer to act upon a hunch in choosing his episodes, and to trust to his nature in governing the flow of feeling. In another place Mr. Warren quotes Coleridge on the imagination, that when “the imagination is conceived as recognising the inherent interdependence of subject and object (or complementary aspects of a single reality), its dignity is immeasurably raised.”

The question of the relation between subject and object, feeling and episode, seems to me one of the grand questions, and in Mr. Warren’s fiction the crucial matter. “Blackberry Winter” exemplifies a natural law, true to Coleridge’s sense of imagination and reality, interdependent. The reality proffered by the story gives an impression of being single, that is to say, single-minded, and I take this to be a proof of its validity. But often in Mr. Warren’s longer fictions and especially in his big novels I find the relation between episode and feeling insecure, and generally the feeling is exorbitant. Feeling and interpretation flow in, but their abundance is often gross, if we think of what occasioned them.

Meet Me in the Green Glen deals with the trial of Angelo Passetto for the murder of Sunder Spottwood. Like Mr. Warren’s World Enough and Time, it is a story of sin and expiation, and it is concerned more with the motive than the deed. Mr. Warren starts well back from the crime, and he comes to the fifth act of his drama only when he is good and ready. The theme is what Jeremiah called it in World Enough and Time, “the crime of self, the crime of life.” Making subject and object interdependent once and for all, Jeremiah says, “The crime is I.”

I have a feeling that Angelo Passetto would say the same thing if he could. But this is the trouble with the new novel. Mr. Warren’s narrator said of Jeremiah that “out of his emptiness, which he could not satisfy with any fullness of the world, he had to bring forth whatever fullness might be his.” Such an effort justifies the high rhetorical mode of the book. But Jeremiah was capable, at least he could make the effort, and the style of the book registers the stress of feeling and perception. Poor Angelo can’t even make a start, he is a clod, capable of nothing. From his emptiness he can bring forth nothing, and to such a loser the world is merciless.

Not a single character in the new book is capable of Jeremiah’s effort: not Cassie Killigrew, Cy Grinder, Sunder, least of all Murray Guilford, lawyer, state prosecutor, at last judge. Henry James gave as the sign of the born novelist, in his essay on Turgenev and Tolstoy, “a respect unconditioned for the freedom and vitality, the absoluteness when summoned, of the creatures he invokes.” But Mr. Warren’s new characters have no freedom, and only as much vitality as is consistent with imprisonment, a life sentence in their nature. They are so empty that he must himself produce the fullness of the world and give it to the narrator, the narrative voice.

Mr. Warren has to do that as well as everything else. He must do what these wretched characters cannot do for themselves: imagine, understand, perceive. Their slightest gestures must be eked out, glossed, driven to mean something. The narrative voice never rests. If Angelo lies on a bed and smokes a cigarette, the voice interrupts:

He was about to dive into that depth where there wasn’t any Time, and he would at last lie on a bed, staring at the ceiling washed by a raw light cast from below, from the unshaded lamp set on a chair by the bed, and now and then put a cigarette to his lips to draw the smoke into his lungs and then expel it deliberately from his nostrils in two curling grayly exfoliating, vanishing stalks.

Angelo cannot think in any language, his mind is as rudimentary as his English, but the narrator out of his own fullness gives him lavish gifts of meditation:

Advertisement

Was this the way things always were in the end? If all you had out of living was the memories you couldn’t remember the feelings of, did that mean that your living itself, even now while you lived it, was like that too, and everything you did, even in the instant of doing, was nothing more than the blank motions the shadow of your body made in those memories which now, without meaning, were all you had out of the living and working you had done before?

The narrator is equally generous to all his characters: each of them, even Cy Grinder, is amplified, protected, filled from resources not his own. After a while, and no wonder, they all sound the same.

The trial itself is the best part of an uneven book: in court, even a narrative voice as insistent as Mr. Warren’s keeps pretty quiet, and the significance of word and deed is mediated through the courtroom forms, procedures, conventions. Elsewhere Mr. Warren should have told his narrator to shut up. Like Murray Guilford, the narrator “could sure swing the English language,” but the swinging wrecks what might have been a good novel.

The Condor Passes is a different answer to the question of episode and feeling. Shirley Ann Grau has kept herself as far out of the book as is consistent with writing it. Feeling and interpretation are just as lively in her as in Mr. Warren or any other good writer, but she holds them in abeyance, their time will come but not yet. Each incident is given with as much fullness as its participants deserve, but it is surrounded by silence; either it justifies itself or it does not. If the acts and events are not as opulent as they would be in Utopia, so much the worse, they must do the best they can, the novelist is not going to pretend that they are more than they are.

The theme is given in the title. “What’s a condor?” someone asks, and the Old Man answers, “A big bird…a black bird. They used to fill the feathers with gold after he was dead.” I can’t see that the symbol does anything for the book, and Miss Grau comes back to it at the end for no good reason. The novel already has nearly as much as it needs, for theme: money and a family to spend it. If The Condor Passes is more variously interesting than, say, Meet Me in the Green Glen, one reason is that Miss Grau’s narrative voice keeps its mouth shut until it has something true and relevant to say. Another is that the pertinent feelings and interpretations come from the several characters, individually, or they do not come at all. Each character is given his day in court, beginning with Stanley, forty-four, the useful Negro in Gulf Springs, Mississippi. But Stanley is small stuff, the big man is Thomas Henry Oliver, without him there would be no story. Thereafter the saga includes his wife Stephanie, his girl Helen Ware, his children Anna and Margaret, his servant Robert Caillet, Robert’s marriage, sundry affairs, and a boy Anthony who drowns himself.

One of the chief graces of the book is the imaginative control with which Miss Grau moves the story from Stanley to the Old Man to Robert to Anna to Margaret to Anthony and back at last to Robert and Stanley. Each viewpoint is held with just enough emphasis to define it, there is no impression of force or excess. Perhaps Margaret gets more space than she is worth, but generally Miss Grau is judicious in these allowances. She is fair even to characters who have done little to deserve justice, but she does not lick their boots. Anna, for instance: a character of force, much of it deadly, devoted to the art of possession. I recall with special pleasure a scene, the day before Anna’s wedding, when she wanders through the house that she means to buy. “This is me,” she reflects, “I make things belong to me.”

Miss Grau’s policy is clear. She is determined to give her characters free range, subject only to the limitations implicit in the nature of things. As for their own natures, they are welcome to do what they like with what they own. So the novel hovers upon questions of property, possession, rights, duties, needs, license. Miss Grau attends to her art with a corresponding sense of law and limitation. She does whatever she can manage with characters, she invents new characters when she feels in need of them. If there is something that her characters cannot reasonably see or feel, her novel must do without it: that she, the novelist, can see or feel it is not enough reason for including it. In short, whatever cannot be achieved by attending to a large family of characters had better be left alone.

Advertisement

Miss Grau works by concentrating on one thing, one character, at a time, and her art is exhilarating in its precision. But she is not exceptionally good when it is a question of latitude. The Condor Passes is a family saga, and much of it takes place in New Orleans, but it is hard to feel that New Orleans makes any difference or that the saga would have been another thing if it had happened in Detroit. Again the years are marked, there are references to Robert away in England, fighting his war, but it might as well be another war and another country for all the difference it makes. The book has very little feeling for the millions of lives that it does not describe. Every episode is vividly illuminated, but there is very little sense of a world and a time between the lights. The public world does not press upon Miss Grau’s private people, and we could be forgiven for thinking that it has gone away. The characters have lively relations to one another, and equally lively relations to themselves, but they do not bump against strangers, they are rarely aware of a world going about its alien business, indifferent to the Olivers.

Miss Grau tells us, in each case, what she thinks we ought to know, and nothing more. Her tact is blessed. But she virtually conceals from us, while the novel lasts, the fact that other forms of reality are present, even if we do not see them. She nearly prevents us from knowing those forms of reality which James called “the things we cannot possibly not know, sooner or later, in one way or another.” In a richer novel we would hear noises which we would not interpret, except in the ordinary way as the buzz of things. The Condor Passes is all foreground, very little background, everything is presented in the same degree of lucidity, that is, a high degree. But after a while the lucidity begins to oppress, and I think we would believe more if we were shown less, or if a little public confusion were to assert itself against the private gleam.

Such considerations do not arise with Edsel, Karl Shapiro’s first novel about a famous poet saved by the love of a good divorcée. We are asked to believe, while the book lasts, that Edsel Lazerow is teaching creative writing at a small midwestern college. I have no problem thus far. The book begins with Edsel’s survey of his recent State Department tour to Zagreb, Hamburg, Frankfurt, Rome, Rimini, London, Oxford, Chicago, and so forth. Much of this sounds like the boozy reminiscences of a tourist, playing back his tape of sex and sin in Copenhagen, Tijuana, London, Paris, Amsterdam. The story proper then begins. Mostly this involves randy women, faculty squabbles, a demo, a cock fight, the Janiczek party, one or two essays in sexual perversion composed by a woman called Wanda, while all the time our Edsel is trying hard to make it. At the end, having rid himself of Wanda, he makes it with the good Marya Hinsdale to the accompaniment of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Since the book is supposed to be about love and politics, it ends thus:

I poised in mid-air and plunged down between her thighs, rolling and pitching like a ship, and I exploded into a red, white and blue orgasm spangled with silk and iridescent stars and golden fringe.

Never had I loved my country more.

Now a man writing such prose at such a time is not supposed to be on oath, but I found the rest of the book just as hard to take as that finale.

“You know, Ed,” one of his girls says, “you don’t make a very convincing savage.” Well, I found him more convincing in that role than in his role as poet. He teaches poetry, and he gives us a few samples of his classroom talk, invariably commonplace, but he is never shown reading a book, and the only example of his verse is the following:

The sun, my love, is telling me the time,

The sunset strokes the rib-cage of my books

My books will be your books and all will rhyme

And meet in the rhyming couplets of our looks.

To be fair, Edsel knows this is junk and he throws it away. But we never find him trying again or better. As for his sexual life, that seems to go best when he takes it as a spectator sport, until the happy ending with Marya. Of his bohemian activities he says, making sure to keep the saying till the end:

I was never more than a tourist in that realm of mildew and dryrot. But that it was the grubbiest of bohemias I never doubted; I must confess that the very grubbiness attracted me, but then, in those days, nothing aroused my attention except failure and failures. Wasn’t I one myself?

But Edsel is a bore.

The trouble is that he protests too much. If he takes a plane to Frankfurt, it is “a half-empty Pan-Am monster.” If he gets into a car, it is a “brutally black plain American Plymouth.” The hotel in Rome is “the nasty little hotel off the Via Veneto.” England is “grim green grimy ungrate ingrate no-longer-great England. A slum. A dream. Bad dream. A nightmare.” He walks out of an airplane thus: “I walked through the Fallopian tube of the covered gangway that had telescoped out to kiss the exit of the plane.” Students on the campus are “bacterial colonies of bright-colored students pausing and moving uncertainly in all sorts of directions.” “But I knew I had to,” he says, “knew I must lead her through the dying-out inferno of my past.” And to Marya he says:

What I mean is that I am climbing out of a rotten world into myself, which I always thought of as a good place, not because I thought I was superior but because I know what happiness is, what beauty and goodness are, even what kindness is, and all those things were dirtied by the people I trusted most, by the people who knew better and who had the good things in their keeping.

Immediately after, Edsel asks Marya, “Do you know what I’m talking about, or care?” and the good divorcée answers, “I don’t know, but I want to hear.”

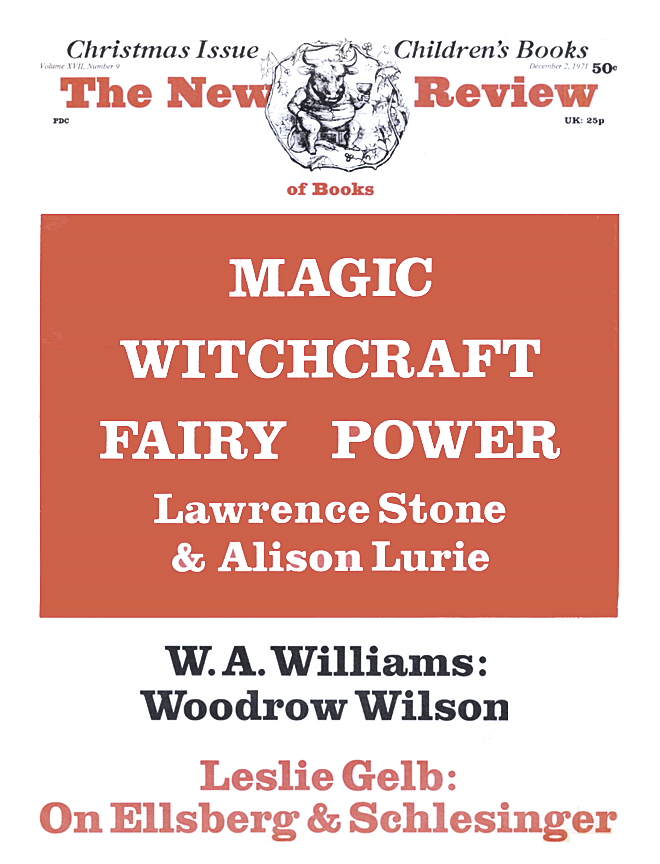

This Issue

December 2, 1971