The Handlins’ new book can best be described as a rather ill-tempered polemic against the “troublemakers” of the Sixties, preceded by a 257-page historical introduction. The historical sections of the work are only tenuously related to the attack on student radicalism; indeed, they sometimes tend to undermine it.

What the Handlins think of student protest is already familiar to readers of Commentary and The Atlantic. Student radicals, in their view, are “rebels without a cause,” pampered children of affluence. They have been spoiled by permissive parents and indulged in their wanton assault on the university by teachers trying to recapture their youth. Today’s children have never known the meaning of a hard day’s work. “Accustomed through youth to the immediate gratification of all demands, they had never learned the need for deferment of any desire.” Since they are bent on “pure destructiveness,” it is evidently unnecessary for their adversaries to reflect on the ostensible issues of their protest—Vietnam, racism, the state of higher education.

This attack on the student radicalism of the Sixties seems to imply among other things the existence of a former golden age, when academic life was untroubled by unruly students or low academic standards, which according to the Handlins have now reached the point of collapse. Yet the historical sections of Facing Life, sketchy as they are in many places, show that American colleges in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries endured chronic student disorders. They suggest, moreover—although the Handlins might object to this interpretation of their chapter on the period between 1870 and 1930—that if these disorders abated somewhat in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it was not because the university had finally become a genuine community of scholars but because fraternities, athletics, and other outlets of this kind played an increasingly prominent part in student life.

In the course of their polemic against student activism, an outburst doubtless provoked in part by recent events at Harvard, the Handlins evoke the memory of an earlier Harvard. Charles William Eliot, they claim, transformed “a boys’ institution of clerical antecedents into a center of scholarship the influence of which would radiate throughout the whole culture.” In recent years what has seemed notably to radiate from Harvard is a certain high-handed approach to foreign policy, based on heady visions of American world power, contempt for the electorate, and school-masterish disdain for critics of American actions abroad, who are given “low marks” by such paragons of humane learning as McGeorge Bundy.

But this is no doubt the misguided perception of an outsider. The point is that the Handlins’ account of Eliot’s major reform—introduction of the elective system—suggests that whatever scholarly achievements it made possible were paid for by sacrificing the possibility of an intellectually coherent undergraduate curriculum and by chopping up the body of knowledge into meaningless fragments, called “departments.”

The Handlins observe that the elective system represented a compromise between the demands of the undergraduate college and the research-oriented graduate and professional schools that were being superimposed on it. “The hope that the lecture system would transform the teacher from a drillmaster into a creative scholar depended upon giving the professor enough latitude to present a subject he knew thoroughly and yet relieving him of students for whom attendance was an unwelcome task.” The trouble was that the elective system also relieved the faculty from the need to think about the broader purposes of education—including the possibility that for many students attending any classes was an “unwelcome task”—and about the relation of one branch of knowledge to another. At the same time, the union of college and professional schools in the same institution preserved the fiction of general education, on which university administrators heavily relied in their appeals for funds.

The ideal of general culture, to which the universities continued to pay lip service, represented not a genuine integration of learning but a “gentlemanly” conception of college life, in the Handlins’ phrase. Even after their partial absorption by the university, the colleges continued for the most part to serve as centers of genteel dissipation. The students “absorbed an awareness of the value of ideas”—one wants to add, if they absorbed such an awareness at all—“…not so much from instruction in the classroom as from a general sense of the importance the [academic] community ascribed to them.” This is a modest but probably accurate assessment of the pedagogical achievement of the American university during what the Handlins consider its prime—roughly the period from 1870 to 1960. It is an assessment based on sober historical reflection, as opposed to the polemical needs of the moment.

At the end of their book, however, when the Handlins take up the cause of civilization against the barbarian hordes allegedly threatening it, a very different picture of that period emerges. In the despair of the moment—the despair to which the new left has driven so many scholars—the universities of an earlier time now appear in retrospect as “little enclaves of learning,” which according to the Handlins successfully “associated maturity with the life of the mind and created durable links to learning among hundreds of thousands of men and women, the alumni otherwise totally occupied with the work of the material world.” As a statement of the ideal a liberal arts college might seek to attain (if it has any reason for being at all), this is unexceptionable, but as a description of reality, it is called into question by the Handlins’ own account of the university’s development, which shows that any learning that rubbed off on students was largely accidental.

Advertisement

Far from associating maturity with the life of the mind, college life has typically encouraged Americans to associate it with the loss of youth and glamour. If the college years are so often described by Americans as the best years of their lives, it is surely not because alumni associate maturity with the life of the mind. Having experienced college as a prolonged holiday, as sex without responsibility, as drunken conviviality, as in short a prolongation of adolescence without its parental restraints, college-educated Americans tend to perceive maturity as a drastic narrowing of their opportunities for play and particularly of their sexual lives.

How else can we explain why the forms of adult conviviality—the cocktail party, the country club, furtive wife-trading, football week ends—so often model themselves on student social life? These patterns, faithfully chronicled by O’Hara and Fitzgerald (and more recently by Nichols and Feiffer), have been breaking down as competitive pressures in college become more demanding and the frivolities of a more innocent age lose their appeal; but for a long time, the chief contribution of college life to the maturing process—if by maturity one means the growth of wisdom and judgment, as distinguished from the reluctant assumption of domestic and professional responsibilities—seemed to be to retard it indefinitely.

The best that can be said about the American university in what might be called its classic period is that it provided a rather undemanding environment in which the various groups that made up the university were free to do much as they pleased, provided they did not interfere with the freedom of others or expect the university as a whole to provide a coherent explanation of its existence. The Handlins’ own description of this arrangement seems a little askew: in their words, the student was free “to learn and play,” the professor “to teach and study,” and the alumnus “to provide funds, each confident that his own interests would stand in satisfactory balance with the others.”

They neglect to mention the administration, which emerged not simply as one more element in a pluralistic community but as the only body responsible for the policy of the university. The decision to combine professional training and liberal education in the same institution, and the compromises that were necessary in order to implement it, not only relieved the faculty of any responsibility for thinking about the underlying purposes of undergraduate education but rendered the faculty incapable of confronting larger questions of academic policy. These now became the responsibility of administrative bureaucracies, which grew up in order to manage the sprawling complexity of institutions that included not only undergraduate and graduate colleges but professional schools, vocational schools, research-and-development institutes, area programs, semi-professional athletic programs, hospitals, large-scale real estate operations, and innumerable other enterprises.

The corporate policies of the university, both internal and external—addition of new departments and programs, cooperation in war research, participation in urban renewal programs—were now made by administrators, and the idea of the “service university” or multiversity whose facilities were theoretically available to all (but in practice only to the highest bidders) justified their own dominance in the academic structure. The faculty accepted this new state of affairs because, as Brander Matthews once said in explaining the attraction of Columbia to humane men of letters like himself, “so long as we do our work faithfully we are left alone to do it in our own fashion.”

The students accepted the new status quo because they had plenty of non-academic diversions, because the intellectual chaos of the undergraduate curriculum was not yet fully evident, because the claim that a college degree meant a better job still had validity, or because in its relations to society the university seemed to have identified itself with the best rather than the worst in American life.

What precipitated the crisis of the Sixties was not simply the pressure of unprecedented numbers of students, to which the Handlins attach great importance, but a fatal conjuncture: the emergence of a new social conscience among students activated by the moral rhetoric of the New Frontier and by the civil rights movement, and the simultaneous collapse of the university’s claims to legitimacy. Instead of offering a rounded program of humane learning, the university was now seen to provide a cafeteria from which students were to select so many “credits.” Instead of diffusing peace and enlightenment, it allied itself with the war machine. Even its claim to provide better jobs eventually became suspect.

Advertisement

It was no accident that the uprising of the Sixties began as an attack on the ideology of the multiversity and its most advanced expression, the University of California at Berkeley; and whatever else it subsequently became, the movement represented, at least in part, an attempt to reassert faculty-student control over the corporate policies of the university—expansion into urban neighborhoods, war research, ROTC. Neither the anti-intellectualism so often associated with the student rebellion nor its underlying despair should prevent us from seeing that the development of the American university—its haphazard growth by accretion, its lack of an underlying rationale, the inherent instability of the compromises that attended its expansion—rendered such an accounting almost unavoidable.

Instead of bemoaning the loss of former glories (most of them illusory), we should ask whether higher education in the United States did not take a fundamentally wrong turn in the 1870s and 1880s, for which we are only now beginning to pay in full. What would have been the consequences of a stricter separation of professional training from undergraduate instruction? It is not easy to show that the union of the two has had a liberalizing effect on the professions; its main effect seems to have been to hasten the competitive upgrading of vocations to full professional status, as one group after another seeks the prestige of the advanced degree.

Much of the recent clamor for “relevance” reflects an awareness that there is an increasingly remote connection between degrees and the training actually required for most jobs. The solution, however, starts not with changing the content of courses but with getting rid of the absurd idea that courses—and colleges—are the only means to an education. The whole system of compulsory schooling needs to be reconsidered. Rather than trying to reform and extend the present system, we should be trying to restore the educative content of work, to provide other means of certifying people for jobs, and to hasten the entry of young people into adult society instead of forcing them to undergo prolonged training—training which, except in some of the older professions, has no demonstrable bearing on qualifications for work. This does not mean that critical thinking and humane learning should be neglected. We should be making it possible, in a variety of ways, for people to learn and to have time for leisure, reflection, and experiment throughout their lives and not primarily in a few segregated high school and college years.

In the earlier portions of their narrative, the Handlins trace the gradual substitution of schooling for apprenticeship and other forms of experience, and their account by no means encourages the conclusion that the change was an improvement. They comment in passing on “the marginal value” of formal education in the early nineteenth century and note that institutions of higher learning proliferated in this period not in response to genuine social or intellectual needs but as a result of “rhetoric, of inflated ambition, and of sectarian bickering.”

Their dogged insistence, here and in their other books, on seeing American society as classless, fluid, mobile, and abounding in opportunities for self-advancement, prevents them from seeing another side of the displacement of apprenticeship by schooling—namely that it led to a hardening of class lines, as educational advantages accumulated in the upper bourgeoisie and the professional and managerial strata. “American society,” they blithely write, “was too fluid to permit the wealthy permanently to dominate the culture.” Nevertheless they see quite clearly that compulsory schooling triumphed largely because reformers succeeded in convincing the public that adolescence was a social problem for which detention in schools was the cure. It was only then that Americans fully accepted what the Handlins describe as “the belief that the school was the nation’s only educational institution.”

The Handlins understand both the strains and the irresponsibility imposed by prolonged adolescence and give a sympathetic account of them. They see that the adoption of universal schooling was part of the same historical process by which young people were excluded from social labor, given a special status, and segregated in special institutions. Unfortunately they see no connection between these developments and the recent turmoil in our schools.

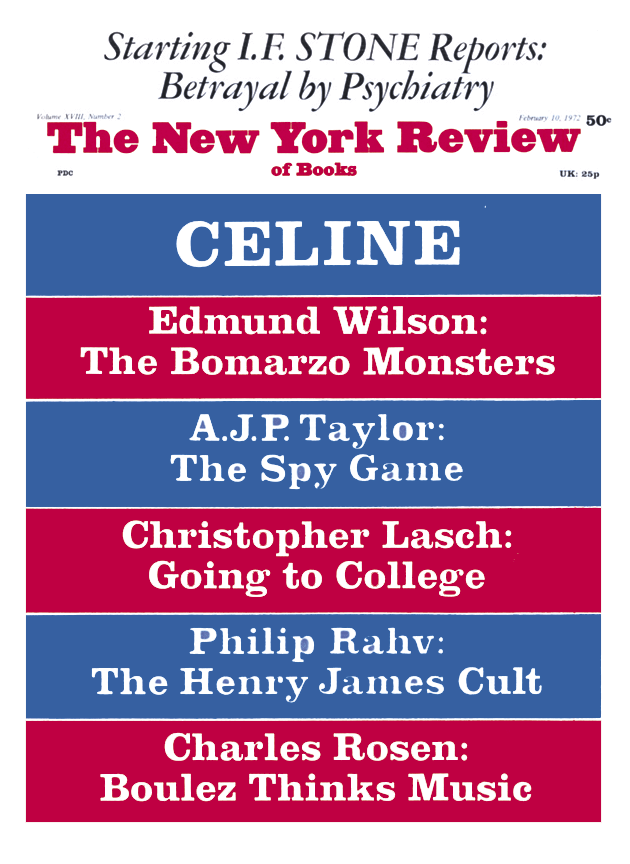

This Issue

February 10, 1972