All the books under review deal largely with the experience of American blacks or women, and all are the products of commercial publishers who sense a new market. Not merely—perhaps not even primarily—a market among young readers interested in history, but among teachers and librarians who want children to read books on these subjects, and who will be vulnerable to criticism if their schools and libraries fail to acquire them.

Ostensibly, the audience for these books consists of “young readers” between the ages, roughly, of ten and sixteen. In fact far more of these books will be bought by the education industry itself—schools and libraries—than by children or their parents. So the books show us as much about what adults think should interest young readers as about what does interest them. These educators and publishers, moreover, seem not to have considered whether young people between ten and sixteen need a special historical literature at all.

No doubt most younger children want to read books written especially for them, but by the time they reach the age for which these eight books are intended, they should be able to read any thoughtful, well-written book. Of course, while an older audience with a particular interest in history may tolerate overspecialization, ponderous prose, and triviality of subject matter (all words for what kids call boring) as the price of erudition, the tolerance of youth is likely to be considerably lower. But this merely emphasizes the need for clearer, more imaginative writing by all historians, rather than for the creation of a historical literature for “young readers.”

Nevertheless, so long as they believe a profitable market exists, publishers will continue to produce historical literature for older children. The seven authors represented here have different ideas of what constitutes history for the young. Some have written traditional texts, stressing facts, dates, and major events. They differ from college texts mainly in their use of simpler language and in the lack of footnotes and long quotations. Others have written biographies, obviously designed to encourage a young reader to “identify” with “relevant” figures of the past. And some have attempted to re-create the social life of the past through the documents or folk tales of the period.

These books, then, seem to have as little in common as would eight “adult” history books taking similar approaches to teaching the past. But they all share explicitly or implicitly another purpose—not merely to impart historical information but to teach moral and political lessons. The books all reflect an assumption that they are to serve as what are now called “modes of socialization,” as sources of values, aspirations, and models to follow whose influence lasts far beyond childhood. Whether they will have this effect is a different matter. But all seven writers, including the academic historians Allen Trelease and Abraham Chapman and the well-known black writers Julius Lester and John O. Killens, have the view that young readers, especially those from minority groups whose history has until recently been largely ignored, need a “usable past”—a sense of history which will help shape their lives and politics, and which they cannot obtain from “adult” histories.

Like many historians writing popular books for adults, these writers try to be historical, political, and interesting at the same time. Some, however, fail at the most elementary requirement of history, accuracy. The usefulness of Robert Goldston’s The Coming of the Civil War is destroyed by a large number of historical errors, such as his statement that at the Constitutional Convention in 1787, Jefferson, Franklin, Madison, and Adams proposed the complete abolition of slavery. Jefferson and Adams were not even there, while Madison and Franklin made no such proposal.

More subtle than factual errors, but equally damaging to the usefulness of some of these books for teaching history, is the feeling on the part of some writers that they must simplify the past, discarding historical complexity in the hope of making the story clearer and more accessible. Goldston can again serve as an example. His version of the origins of the Civil War is essentially the old, hopelessly oversimplified story of a North motivated by moral outrage over slavery and of an evil, racist South. Northern racism is barely mentioned, yet no account that ignores it can explain why, as Goldston notes at the conclusion of his book, “Black Americans came into something less than their heritage” after the Civil War.

But accuracy and historical subtlety by themselves are no guarantee of a good book, a fact illustrated by Allen Trelease’s Reconstruction. Well-researched and up-to-date in every respect, Trelease’s book is an excellent example of a traditional children’s history. And, should anyone miss the “relevance” of Reconstruction for the present, he closes with a comparison of the first and second Reconstructions, drawing the moral that it is much easier to legislate equality than to practice it. Essentially, however, the book is a textbook whose style is not likely to win many converts to history, young or old. Its appeal will largely be to teachers and librarians, and to younger readers who already have an interest in the past.

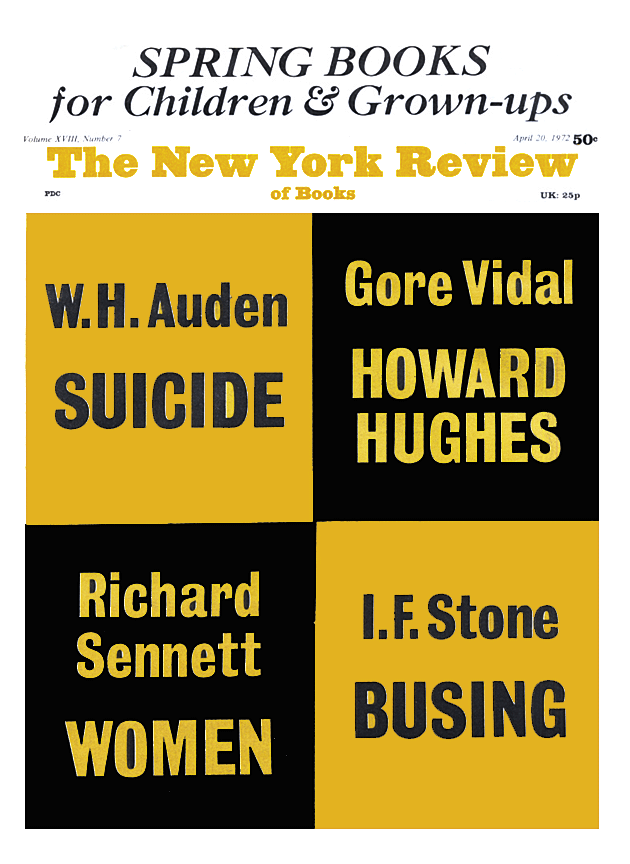

Advertisement

Of the books reviewed here three are biographies—of Martin Delany, Denmark Vesey, and Elizabeth Blackwell. Until recently biographies in black history usually celebrated such figures as Crispus Attucks and George Washington Carver, men who contributed to the main tradition of American history and whose achievements presumably demonstrated the worthiness of blacks to share to some degree in American life. Vesey and Delany, however, were men whose concern for white American political life was secondary, and whose main contribution was to the black community. Both were extremely cynical about the values and claims of white society and are now viewed as heroes precisely because they believed that blacks must rely on their own efforts to achieve liberation, and that violence is an acceptable means to that end. Similarly, Elizabeth Blackwell is a suitable subject because she spent most of her life struggling against the prevailing assumptions about woman’s “place” that now concern the women’s movement.

Finding new heroes has meant reconsidering old ones. There are few good words in any of these books about the usual “great Americans.” In John Killens’s historical novel based on the life of Denmark Vesey, Vesey calls Washington and Jefferson “pious-talking bastards” (words that probably reflect Killens’s view more accurately than Vesey’s). The only whites who seem to qualify as admirable are Thaddeus Stevens and John Brown, both of whom made dramatic gestures against white assumptions about race.

The young, of course, may find it difficult to believe in glorified, saintly portraits of historical figures. But a thoughtful and subtle characterization of an intrinsically interesting subject carefully set within his period can still be “inspiring.” By this standard, the most successful biography here is Dorothy Sterling’s life of Martin Delany. Delany’s career provides a useful instrument for introducing some of the major figures and movements of nineteenth-century black America. Delany was the editor of a black newspaper, a leading abolitionist, the leader of an expedition to Africa to consider the possibilities of black emigration from America, the first black major in the US Army, and an important Reconstruction politician.

He knew Frederick Douglass and John Brown, and even met with Abraham Lincoln at the White House. Delany also encountered racism as he moved through American society—as a young free black whose family was forced to flee Virginia for the crime of having allowed him to learn to read, and as a medical student expelled from Harvard Medical School on the demand of the white students. Delany was the “father of black nationalism,” a man who wore a dashiki in America, who called blacks “a nation within a nation,” and who insisted on racial pride and self-help.

Delany’s life exemplified the dilemma that many blacks face today—how to define themselves while being both black and American. Mrs. Sterling rejects the temptation to imply that Delany solved this problem; his “relevance” today lies in his having faced it. Mrs. Sterling leaves no doubt that for all his identification with Africa, Delany was irretrievably American—and middle class. He put great stock in the temperance movement as one solution to blacks’ problems and on his trip to Africa he was deeply offended by the sight of bare-breasted women. During Reconstruction, Delany opposed the confiscation of planter lands, believing that blacks should have to work and save for land like anyone else. As described by Mrs. Sterling, Delany was a complex man, who made mistakes, but whose mistakes do not diminish his stature.

Like Delany, Denmark Vesey, the leader of a nineteenth-century slave conspiracy, is an authentic black hero. Like Delany’s, his life exemplifies black self-help and racial pride. Both biographies have beautiful jackets by the same artists, Diane and Leo Dillon. But there the resemblance between them ends. John Killens is not a subtle writer. Denmark Vesey and his men, he writes, were “Black freedom fighters,” who knew that “blood would have to flow before Black men would be liberated.” Vesey is described as “an expert in the manly art of self-defense,” who had “outfought many a man in his day, especially white men.” The language of the book, in other words, reflects the politics of the 1960s as much as the history of the 1820s.

Of the three goals of history for the young—history, politics, and interest—the last two are the most important to Killens. His book must therefore be judged, in part, as a political document, and here it is most vulnerable. Faced with the lack of evidence about Vesey’s life, Killens chose to write fiction, making up details of character and plot. For instance, Vesey had a wife, Beck, but we know virtually nothing about her. Killens imagines what she was like, and the result is unfortunate. There is nothing wrong with describing Vesey as “a fine specimen of manhood, the kind that men and women turned to stare at in the streets,” a majestic, imposing figure. But why must his wife be described only as “this tender woman of the lithe body, warm and full and amply rounded, soft of eye and voice and touch and movement,” for whom Vesey is “king and master…her religion and her patriarch.” “Denmark,” Killens writes, “would have his manhood,” but Beck’s womanhood seems to have consisted only of raising his children and being available when he wanted to see her. With no historical evidence for saying so, Killens describes Vesey as telling her nothing of his planned uprising.

Advertisement

Leah Heyn’s Challenge to Become a Doctor is one of the first publications of the Feminist Press, whose self-proclaimed goal is to publish books on women’s history, including works “about one-parent families and about families in which both parents work and share household responsibilities.” Elizabeth Blackwell, America’s first woman doctor, is obviously an appropriate subject, and a welcome change from the scores of books for girls about nurses, teachers, and airline stewardesses. Her effort to obtain a medical education encountered obstacles and required a perseverance that could make her story of strong interest today. Moreover, while she never married, Blackwell adopted and raised a daughter on her own. She thus challenged nineteenth- and twentieth-century stereotypes in her public and private lives.

But if Challenge to Become a Doctor is obviously “relevant,” its writing is uninspired and its view of the past oversimplified. The dean of a medical school, for example, explains his opposition to female students by saying that he fears women “will put men doctors out of business.” The social setting of Elizabeth Blackwell’s life is largely ignored; as is the question why so many of her contemporaries were hostile to her. The book includes some dull illustrations and a long pedestrian poem inserted in the narrative.

One problem with the biographical approach to history—for the young or adults—is that it tends to create a distorted, “great man” view of the past. Historical understanding of slavery will come not only from reading about Denmark Vesey but from knowing something of the experiences of the millions of slaves who never took part in a rebellion. The documentary collections of slave narratives and reminiscences, edited by Abraham Chapman and Julius Lester, are “history from the bottom up,” and attempt to provide dramatic portraits of slave life, allowing the reader to experience first-hand, as Lester’s title suggests, what it was like “to be a slave.”

These books, however, only serve to reinforce one’s conviction that special history for young readers is unnecessary. The slave narratives were originally written for adults, and are today used widely in college classrooms. If they are successful in giving young readers an understanding of slavery, this is simply because they are good, interesting history. They also serve to illustrate the political uses of history for the young. Originally produced as political documents, intended to arouse a Northern white public against slavery, they were long ignored by conservative historians, and are reprinted today for political purposes similar to those for which they were originally written.

Slavery, however, while a clear moral issue, was enormously complex as an institution, and Chapman’s selections from the narratives lack this sense of complexity. His collection has much on abuses such as whipping and the separation of families, but little on the texture of slave life. Julius Lester’s collection of more than one hundred brief excerpts from the narratives and reminiscences, on the other hand, is much more aware of the problems of accurately describing the peculiar institution.

Lester’s perceptiveness becomes apparent when we compare each editor’s selections from one of the best-known narratives, Father Henson’s Story. Chapman includes one chapter describing Henson’s earliest years and the cruelties visited upon his father, and another describing his escape from slavery. The most revealing part of the narrative, however, is a description of how Henson, ordered by his master to conduct a group of slaves from Virginia to Kentucky, took them to Ohio, where he discovered that, by virtue of being in a free state, they were all legally free. But Henson was so impressed by the responsibilities his master had given him that he took the slaves on to Kentucky. Lester includes this part of the narrative, clearly showing how some slaves could absorb the values of their masters.

Of all the writers, Lester has the clearest idea of how history can be made interesting. His collection of “stories from Black history,” Long Journey Home, is the most lively of all these books, yet it sacrifices no subtlety and makes important points about past and current black life. It is the kind of book that will be valuable both to the young and to adults.

Lester does not feel it necessary to make every black man and woman a superhero. He realizes that there is as much dignity in endurance and survival as in hopeless rebellion. He also sees that it does not detract from the male ego to show women as strong, dignified characters in their own right. “For me,” Lester writes at the outset, “these stories, and hundreds like them, comprise the essence of black history…. History is made by the many, whose individual deeds are seldom recorded and who are never known outside their own small circle of friends and acquaintances. It is merely represented by the ‘great figures,’ who are symbols, reflectors of the history being made by the mass.” Long Journey Home contains six stories from black history, all based on at least some historical fact, and all embellished with historically plausible characters and situations.

The first is set in the post-emancipation South, a time when most of the freed slaves were sharecroppers. Trelease’s Reconstruction gives an accurate enough description of this system and its abuses. But readers are more likely to get the idea from Lester:

“Well, de ducks got me again this year,” one would say jokingly to another on that cold November day when they lined up outside the commissary to settle their accounts. “Cap’n Bryant look in that big book of his and he say he deduck for the medicine I had to have for my chillun, and he deduck for the cottonseed and the new plow and the new shoes and clothes and the chewing tobacco and the snuff for my mama and the moonshine and the food and the rent. And he put all de ducks together and he say, ‘Well, Sam, you owed me two hundred dollars from last year and the cotton you and your family raised brought in nine hundred dollars…. But y’all spent ‘leven hundred dollars for rent and the cottonseed and that new plow and all the rest. So that mean you end up owing me four hundred dollars. Sho’ am sorry about that, Sam!’ ”

Probably the most beautiful story in this thoughtful book is “The Man Who Was a Horse,” an account of a black cowboy rounding up a herd of wild mustangs. It is an extended metaphor for the enslavement of free, proud beings, which ends with this statement about black-white relations and the inability of whites really to understand blacks: “As he led them toward the corral, he knew that no one could ever know these horses by riding on them. One had to ride with them….” Pride in the black experience runs throughout the stories and this may well create in a black audience an eagerness to read other historical works to learn the truth of their past (but not necessarily “books for children”).

And yet even in this excellent book there is a lapse, trivial enough on the face of it, but important when one stops to consider it. The stories are not arranged in chronological sequence, and the reader therefore gets no sense of one of the most important elements of history—the order in which events took place. He must bring to these stories his own knowledge of the historical sequence and setting.

Ironically, Lester’s success only serves to underscore the failure of all these books to justify the existence of a special category of “history for the young reader.” The best among them, Lester’s included, can be read profitably by adults; the worst will likely seem dull and obvious even to children. While it is extremely difficult to know how young people will react to these books, it is not hard to guess how they will sell (that is to say, how they will appeal to teachers and librarians). It is much harder to know if they will be actually read and, if read, whether they will have the intended historical and political effect.

Instead of producing more books of this sort, perhaps a greater challenge for historians would be to reach the vast audience of the historically uneducated, of which children comprise only a small part. At a time when increasing psychological, political, and cultural burdens are being placed upon history, this challenge is real and important. It is not likely to be met either by traditional historical texts or by simplistic stories about the past which ignore the fact that history teaches as many ironies and ambiguities as clear lessons. One can hope, however, that one lesson which can be drawn from historical writing for an unsophisticated audience is that social and political institutions are not immutable—they have been changed in the past and can be changed in the present. An understanding of this is the first element of a “usable past.”

This Issue

April 20, 1972