A brief sketch by Stephen Crane, “An Eloquence of Grief,” written about 1896 when he was still a New York reporter haunting police courts, is a rather cryptic, imaginative account of a routine case and conviction, and it contains a theme which dominated his vast literary output and meteoric short life. The report concerns a girl accused of stealing “fifty dollars worth of silk clothing” from her well-heeled young woman employer. The girl, who is a servant, is tried and found guilty. On hearing the verdict, she makes a sudden outcry.

The tale has an inner logic as it proceeds. In the beginning are the deft, satiric Crane touches, not missing the mood of the spectators, those ritualistic carnivores of conventional society who turn up in some of his longer fiction. They have come to the trial to “wait” for a “cry of anguish, some loud painful protestation that would bring the proper thrill to their jaded, world-weary nerves….” At the end, after the girl is banished to jail, we are offered what might pass for comic relief. The next person on trial is a habitual offender, an old drunk. Though he is not entirely funny as presented by Crane, “an aged toothless wanderer, tottering and grinning,” nevertheless his silly, slurring speech elicits a smile from the court officer. Thus the drama ends.

But the goal was not irony. If one can disentangle the stunning, somehow disembodied detail from what functions as Crane’s plot, one realizes that the salient note was struck well before the finish, when the girl cries out. It was a cry not for audience entertainment. “The loungers, many of them, underwent a spasmodic movement as if they had been knifed.” In fact, “whether innocent or guilty, the girl’s scream described such a profound depth of woe, it was so graphic of grief, that it slit with a dagger’s sweep the curtain of the commonplace….” Its tone was so “universal” of mind “that a man heard expressed some far off midnight terror of his own thoughts.”

According to Crane, his second novel, The Red Badge of Courage, was intended to be a portrayal of fear. But when one looks back over the stories, war memoirs, poems, that seems only part of his aim. Getting clear of mundane appearances, false, dishonest, or pious, or ripping aside the “curtain of the commonplace” (there are the abrupt reverse integers in the poems in War Is Kind)1 represented for Crane not just occasional moments but the psychological condition under which he lived and wrote. The inference is acceptably modern. The timing of the University of Virginia’s publication of The Works of Stephen Crane (currently being issued, a long series with more to come, which is to include every known piece of his creative writing and journalism), its dizzying appropriateness to the hour, will not, one imagines, be immediately recognized. The fact that 1971 was the centennial year of Crane’s birth may well be passed over in a cloud of literary “rediscovery,” and the nature of the man and his work still be ignored.

Like Emily Dickinson, Crane was not a “literary” writer, though possessed of such audacious abilities that the sheer innovative surface of his work may suggest this. The grounds of his achievement were more deeprooted. Crane lived very close to some stormy center of perception. He grasped the straw of writing to “report” what he had seen. J. D. Levenson, in his introduction to “The Monster” (first of the Whilomville tales in the University of Virginia Works), speaks of Crane’s “devastating intuition.” As Levenson says, he “went beyond the objectivity of the cool broadminded reporter and penetrated to a radically different psychological landscape which the moral assumption of his literate audience did not hold.” That may explain why the attempt to incorporate Crane’s style into the history of “naturalism” or other historical movements will go only so far.

Reading through his work detail by detail, not excluding the dispatches from the Greek-Turkish and Spanish-American wars, one is impressed by the startling consistency of his perceptions. His approach was the same to friends, jobs, women—there being no forced or gratuitous difference between what he observed and what he said.

Underlying every event or observed detail, a man, a tree, a war, was Crane’s great skepticism. Engrained in what we do is what we mean. What most engaged his attention during battle, he said, was “the attitude of the men.” Nor did he mean by that any abstraction about patriotism, brutishness, courage. He perceived in people, by way of their motor responses, their unpredictable strains. It was, indeed, what basically interested him, that seething complex of attitudes, out of which erupted the mystery of their action.

To illustrate. In the story “A Mystery of Heroism” Crane relentlessly measures a so-called manifestation of courage, piece by piece, as if he were breaking down a cell structure. A soldier foolishly crosses an enemy line to get a bucket of water. On his way back he encounters a dying officer who asks for a drink. The tone is almost casual, the officer asks and does not beg. Though lying in a hideous position of suffering, trapped under his dead horse, he says: “Say, young man, give me a drink of water will you?” The soldier reacts with a frantic “I can’t.” He runs on a few feet, then turns back and, without knowing why, he pauses, risking his life in that “region where lived the unspeakable noises of swirling missiles” to splash water over the face of the dying man.

Advertisement

Throughout, the soldier’s emotions appear to be nothing but terrified refusal. It is in the pit of reluctance, and with his face “gray” with terror, that he performs the deed. When he returns with the bucket to his companions (their faces are “wrinkled” with laughter, so we can’t tell whether they are scoffing or exalting), somebody makes a misstep and the rest of the water is spilled. “The bucket lay on the ground empty.”

Emptiness is one of Crane’s often repeated motifs. At the end of “Five White Mice,” a story of a near murder in Mexico, the final line is “Nothing happened.” But everything had happened. Or had it? The matter is relative. It is Crane’s ambivalence and his refusal to sum up results that make him so truthful. Daniel G. Hoffman, in his very interesting study The Poetry of Stephen Crane,2 begins with H. G. Wells’s comment on Crane’s work (Wells and Crane were friends in England) as defining “the expression in literary art of certain enormous repudiations.” Hoffman shows how these repudiations operated on many levels, against society, cultural history, and tradition.

Accordingly, Crane’s judgments on himself were severe. When he spoke of The Red Badge after its success (his only one) as being “too clever” and representing too much of the “literary expedient” his position was excessive. The work was on a stylistic plane no other American had yet reached, and it was H.L. Mencken who would later date “modern literature” from that novel. But Crane suspected his own motives, or even saw in his work the slightest trace of imitating shoddy values. By contrast, it is hard to think of any reputedly “committed” writer today who, having made it, wouldn’t at the drop of a hat just continue to snuffle after the gravy.

Crane was a curious product of reform and stability. He was born in Newark, New Jersey, the fourteenth and last child of Reverend Jonathan Townley Crane and Mary Peck Crane. The Crane family could be traced back to before the American Revolution, and were among the earliest settlers and soldiers in Connecticut and New Jersey. They were, in their strong individuality, described by Crane as “pretty hot people.” Mary Peck was the daughter of a line of Methodist clergymen, and both parents were fanatical do-gooders. They were also narrow and unsophisticated, though at Princeton the Reverend Crane had rebelled, giving up the Presbyterian faith and its dogma of damnation for what he considered the more lenient Methodism. As a preacher he was eccentric, believing that helping people was better than giving sermons. Stephen himself, who threw religion over early, referred to it as nothing but a “sideshow.” The Reverend Crane died when Stephen was eight, of overwork.

Some of the Reverend Crane’s published prose and tracts on such subjects as card-playing, loose behavior, and the fall of man are still on file at the Central Branch of the New York Public Library. Mrs. Crane wrote voluminously for the Christian Temperance union and was active giving speeches for various women’s movements. Not to be overlooked was her habit of taking in “unwed mothers” and sticking by the girls until they were on their feet again. She appears to have been stiff-mannered and energetic; her voice Stephen remembered as “sounding like Ellen Terry’s.”

It is safe to suppose that a house open to unwed troubled girls is not likely to be priggish. In 1891 Stephen and an older brother, William, didn’t hesitate to risk their lives trying (unsuccessfully) to save a Negro from being lynched by a crazy Port Jervis mob. Crane never ceased hating mobs. The young Crane was classed as “the wild son of the minister.” Along with being an exceptional baseball player, which his father would have opposed, putting it in the same order as theater-going, whisky drinking, and dancing, Stephen Crane was chiefly interested in cigarettes and girls. Like Dreiser, he seems to have loved women and acted toward them in a way that was, as biographers note, at once “chivalrous and realistic.”

Advertisement

It is not surprising that Crane’s sexual idealism (about which much has been written) should have turned him to prostitutes. He also liked actresses and people he considered Bohemian. What some critics tend to forget, in seeing him psychoanalytically, is how advanced and intelligent Crane was. Like Keats and Schubert, he wrote some of his best work between the ages of eighteen and twenty-six. Consider one of his first published pieces, tossed off in 1888, when he was sixteen, a report on an “American Day” parade in Asbury Park by the Junior Order of United American Mechanics. Crane wrote of the celebration, which he was supposed to praise:

…probably the most awkward, ungainly, uncut and uncarved procession that ever raised dust on the sun-beaten streets.

The onlooking crowd he described as:

…vaguely amused. The bona fide Asbury Parker is a man to whom a dollar, held close to the eye, often shuts out any impression he may have had that other people possess rights…. Hence the tan-colored, sun-beaten honesty in the faces of the other members [the marchers] …is expected to have a very staggering effect upon them. The visitors were men who possessed principles.

It was candor come early to the same unromantic romancer who later would say, “Let a thing become a tradition and it becomes half a lie” and “How are you going to know about things unless you do them?”

After Crane was famous, and had lived in New York City, he did try to make a pleasant-talking pretty girl into his realistic ideal. She was Nellie Crouse, from Akron, Ohio, to whom he wrote (after one meeting in 1895) seven love letters. The sentiments are brilliant, tender, perceptive; also unconditionally honest. And though Crane was a very good-looking man whom a normally good-looking girl would like to have at her elbow, lean, blue-eyed, dashing (a Bohemian friend, however, said that he had the “clean grooming of a wild animal”), Nellie wouldn’t have him. In his revolt against the “smothering conventionalities” and the goads of fashion, he put in their stead what must have sounded bleak to a lively young girl—“courage, sympathy, wisdom.”3 Crane lost what he thought he wanted. Shortly afterward, Nellie Crouse married a man she met at a Harvard prom.

Crane did not exclusively search out prostitutes and older married women, and when he did it was not necessarily for “neurotic” reasons. (Instead, it seems to have been on the sound assumption that experience makes people more interesting.) In spite of Freudian theories about him, he cuts through any possible theories of life; in his work, too, the way in which he shows the complexities of his heroes and villains cannot be encompassed by any systematic analysis. Judged even by present literary standards, where presumably liberated attitudes apply, he still seems light years ahead of us.

There are those who have set up a Freudian case—especially with respect to Crane’s final amorous involvement with Cora Howarth Stewart Crane, twice-married and having ten times as many lovers, who was the madam of the bordello of the Hotel de Dream in Jacksonville, Florida. Cora, the ultimate “older woman,” had barely hit thirty when they met, when Crane was twenty-five. The late John Berryman, in his otherwise rich and fair portrait of Crane,4 made much of these irregularities, one of his theses being that Crane was obsessed with “sexually discredited women” and prone to fall in love with “harlots.”

What emerges on investigation is that Cora was evidently one of those late-nineteenth-century misfits, an emancipated woman with no outlet, either practical or artistic. In 1896, Crane sailed on the ill-fated Commodore, bound for Cuba, and when the ship sank he nearly drowned (the event resulted in the story “The Open Boat”). Cora nursed him back to health, and thereafter became a kind of devoted nurse to his professional needs and physical welfare. Unmarried, they lived together until Crane died of tuberculosis in 1900.

Cora was a libertine and it does credit to Crane that he liked her. She had a flair for books and iconoclastic ideas. His letters and Cora’s diaries emphasize the brevity of love; they are intoxicated with the eventual doom of passion. In Crane’s love poems there is something Baudelairian, the savagery and pleasure in darkness; Cora wrote in her journal:

When we come to think about it seriously it is rather absurd for us to have uninterrupted stretches of happiness. Happiness falls to our share in separate detached bits; and those of us who are wise, content ourselves with those broken fragments….

In “The Violets,” an elegant, refreshing poem, Crane decries possessive love and has violets refusing to live “Until some woman gives her lover / To another woman.” But pain is better than greedy emotions. Besides, possessiveness does not work. Mere acquisition is boring, its own defeat. As for legal wedlock, years before Crane had said to his friend Holmes Bassett that marriage was “a base trick on Women, women, who were hunted animals anyway.” But the two temperaments had much in common, and Cora worshipped Crane and prized his unorthodoxy.

Toward the end of his life, Crane left Cora in England while he returned as a war correspondent to Cuba. He likely saw the pitfalls of a prolonged personal relation, in spite of its convenience. One cannot overestimate, I think, the extraordinary insights of the man—unsentimental, but of some high capacity for identifying with other people (especially those caught in struggle and change, outcasts, exiles on the fringes of life) so that one suspects he was constantly torn apart by the demands of others. Human personalities, men and women, he perceived in a dynamic way, like a natural force, water or electricity. The characters in his fiction are strikingly without features (except in his novel Maggie: A Girl of the Streets he resisted giving them names).

In the nearest he came to a literary redo, credo, during an interview in 1895 with Willa Cather in Lincoln, Nebraska, we are offered no palliative for the lazy. Formulas, he said, were “rot.” And “Yarns aren’t done by mathematics.” “The detail of a thing,” he said, “has to filter through my blood and then it comes out like a natural product but it takes forever.”5

Or is it apparent that Crane found it necessary to merge with his impressions? In any case, he was in his work coming close to a creative science—which in some quarters today might be regarded as the most penultimately modern and detached. It was not that he simply saw the skull beneath the skin but simultaneously he beheld thought processes inside the skull. These thought processes, as they figure in his work, were always volatile, never to be prescribed. To catch the astonishing rapidity of their inconclusive starts and stops (we have only to look at the stories “One Dash-Horses” and “An Experiment in Misery,” where absolutely absolutely weird conjunctions abound) was, Crane believed, the only task a writer with any conscience could set himself.

Both Levenson and Joseph Katz6 have remarked on Stephen Crane’s aesthetic affinities with the pluralism of William James. Certainly the mood is apparent in Crane’s peculiar, episodic style, with its vividly eruptive animisms. Even in the war dispatches nothing is taken for granted. A scouting torpedo boat is a “gnat crawling on an enormous decorated wall.” In the stories, dead and living matter are so quickly interchanged that they seem to describe a universe that is “unpredictable, spontaneous and seldom to be regarded as long continuous.” As Levenson says, “It is a world in which chance, will and general laws all have room to exist.” One may gather that Crane’s so-called philosophical position was, when put into effect, not so morbidly reductive as it sounds.

In fact, his contempt for formulas gave him enormous freedom. Few more uniquely grasped specific colors and forms. Like an impressionist painter he saw that clouds were “green,” and that on the Island (presumably New York’s Rikers) a “worm of yellow convicts” came from the shadow; and in “The Pace of Youth,” one of Crane’s rare love stories, there is in the odd stylization an exuberance that is similar to certain cinematic effects or to ballet. Love is a delicate theater played out against a dazzling world, in this case the Amusement Park, with the proverbial merry-go-round, where:

…there was a whirling circle of ornamental lions, giraffes, camels, ponies, goats, glittering with varnish and metal that caught swift reflections from windows high above them….

And,

The summer sunlight sprinkled its gold upon the garnet canopies carried by the tireless racers and upon all the devices of decoration….

Gloom is not the only aim of freedom. Crane loved scenery, and his eye trained to absorb textures. It is surprising how little of the description dates. In Maggie: A Girl of the Streets there is in the hundreds of Bowery vignettes no taint of the old-fashioned. Crane penetrated to the core; there is a documentary fullness in his description of social nightmares. The little boy “shrieking like a monk in an earthquake,” the tenement building that “quivered and creaked from the weight of humanity stomping about its bowels,” and finally the marvelous, terrible paranoiac craziness of New York, where only the horse-driven vehicles seem of the past, evoke what we continue to endure. Not to leave out Crane’s remorseless unveilings of heinous motive. After Maggie’s suicide, the last scream of pain from her maudlin, boozy mother, “I’ll fergive her, I’ll fergive her,” shows how evil can be counted on to win out. Yet it is the writer’s insight that triumphs, depicting what really is—with all the hard, sensuous ironies.

Hamlin Garland and William Dean Howells became the champions of Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, believing they saw in it a rising star of naturalism. Crane was a naturalist, or could be called one. He would also be labeled a satirist, an imagist, a fabulist (his tall tales of the West are like a blend of Twain and Poe), a parodist, an epic poet, social critic, etc. None of the terms is incorrect, and the categories are incidental.

In England, when Crane and Cora were living at Brede Place, the friendships with older writers, Joseph Conrad, Henry James, Ford Maddox Ford, H. G. Wells, and others, were based on mutual appreciation. But Crane was puzzling to them at times, and not entirely understood. There was the confusion between his being an adored young writer and a gallantly dying figure (Conrad referred, too condescendingly to my taste, to “poor Stevie”) and not enough emphasis on Crane as a man with a distinguished and independent mind. Henry James seems to have been more sympathetic, and probably caught some glimmer of his own American dilemma—or that of the young man who wrote feverishly for money, with potboilers too good for the market.

Between 1897 and 1899 Crane was at the height of his creative powers. In 1898 were published “The Bride Comes to Yellow Sky,” “Death and the Child,” “The Monster,” “The Blue Hotel.” Each is different in structure, like different botanical plants. Notwithstanding, there is the “deceptive simplicity” which Hemingway was said to have invented and also the balancing of a dolorous theme against an easy surface. The tone is almost Mozartian, and rightly what Levenson calls “the test of self-discipline for which the proper rhetoric is understatement.” Yet, for all that, there is the unexpected rush of poetic energy. Of prime interest, I think, is “The Monster,” and for two concluding reasons.

First, the story suggests to me Crane’s most conspicuous concerns brought into a single dramatic focus. He extracts from an obvious event its generally unseen, radical components. In the tale we have compounded social criticism, psychological insight, and Crane’s most sensitive pinpointing of symbolic acts. “The Monster” involves a fire rescue in a small town. Jimmie, a little white boy, is saved by his father’s young black stableman, Henry Johnson. Jimmie survives intact, but the black man comes out of it with face and mind destroyed.

Dr. Trescott, the father of the boy, dedicates himself to taking care of Henry for the rest of his life. But that is not so easy. As soon as the neighbors get over their orgiastic excitement—and again, no one but Crane has ever portrayed so well the appetite for violence as a kind of idiot’s orgasm—as soon as things return to normal, they reject the maimed hero. Because his unnatural appearance repels them (he wears black crepe around his face and sits “an impassive figure on a box”), they try to threaten the doctor into having “the monster” sent away. Over their wish, the doctor chooses his commitment to Henry; so loses his practice and is ostracized. When being urged by well-meaning friends to act otherwise, he replies, “Nobody can attend to him as I do myself.” His life is ruined.

Along with exposing the incipient evil of group emotions, Crane develops here one of his favorite obsessions, that of “rescue.” In “The Monster” the idea has been capsuled into a situation of rescuing the “rescuer” (or, more profoundly, the problem of saving a savior?). This and another recurrent theme, the confrontation with non-identity (powerless people, fallen women, maltreated animals—as in the searing little story “The Dark Brown Dog”—and the nameless victims of war), are fused into a realistic drama with Henry Johnson, the epitome of the nonperson, deprived of face and mind. One can believe it was not by chance that the good-natured, destroyed young man, who might be Crane himself, is depicted as a Negro. But, and significantly too, Henry has been rejected by his own race, the girl he was courting, and his old friends. Even when children exploit the monster’s hideous misfortune, there is something powerful and dignified about him. Horror, it can be said, must be noble, otherwise it is trivial.

Lastly, there is the matter of Crane’s fundamental dispassion. To Crane, the circumstances related to ‘The Monster” might never be changed. Crane’s villains are like blind acts of nature, sea storms, fire, war cannons. Immutably, they confirm the moral emptiness. Likewise, there is Crane’s supposition that the choice of Dr. Trescott was of his own irrational doing and cannot be laid to a master plan of the gods.

In The O’Ruddy, Crane’s last novel, an Irish romance half-finished (and completed by Robert Barr after Crane died), the protagonist is a good-humored fellow, outside morality. Mr. O’Ruddy, the hero, is a young, sophisticated adventurer from Glandore, a gentleman and a rogue, who travels, lives by his wits, connives for a living, duels with villains and hypocrites, and enjoys affairs with available women. Like Stendhal’s Lucien Leuwen, he is at once jaded and eager for life. Though he laughs at any serious meaning, he still follows his passions and his own silly spontaneous taste for new baubles and adventures, high-minded or absurd. (Crane intended a “happy ending,” which Robert Barr completed.)

O’Ruddy is, I think, similar to Dr. Trescott, as well as to Henry Johnson, who, in the midst of the fire and holding Jimmie in his arms, equates having saved a little boy he loves with having, earlier, clutched his hat “with the bright silk band.” The hallucination is authentic, that there should be a resemblance between loving a person and caring for one’s hat! Here is the other side of pessimism. Take Henry’s last impression of a beautiful New Jersey evening, before he undergoes the holocaust. He is spirited, young, wearing lavender trousers; the hour is twilight, he’s on his way to see his girl:

The shimmering blue of the electric arc-lamps was strong in the main street of the town. At numerous points it was conquered by the orange glare of the outnumbering gaslights in the windows of shops. Through this radiant line moved a crowd, which culminated in a throng before the post office awaiting the distribution of evening mails. Occasionally there came into it a shrill electric streetcar, the motor singing like a cageful of grasshoppers, and possessing a great gong that clanged forth both warnings and simple noises….

The young men of the town were mainly gathered at the corners [of a theater] in distinctive groups, which expressed various shades and lines of chumship, and had little to do with any social gradations. There they discussed everything with critical insights, passing the whole town in review as it swarmed in the street. When the gongs of the electric cars ceased for a moment to harry the ears, there could be heard the sound of the feet of the leisurely crowd on the blue-stoned pavement, and it was like the peaceful evening lashing at the shores of a lake….

What does this have to do with the monstrous event that is coming? Everything and nothing. Stephen Crane was one of those radically gifted people possessed of a bitter maturity and a prodigious, eternal youth. On June 5, 1900, he died of tuberculosis in a sanitarium at Badenweiler, Germany, at the age of twenty-eight.

Four years earlier he had written to Nellie Crouse: “If the road of disappointment, grief, pessimism is followed long enough, it will arrive there. Pessimism is, itself, only a little, little way, and moreover, it is ridiculously cheap. The cynical mind is an uneducated thing.”

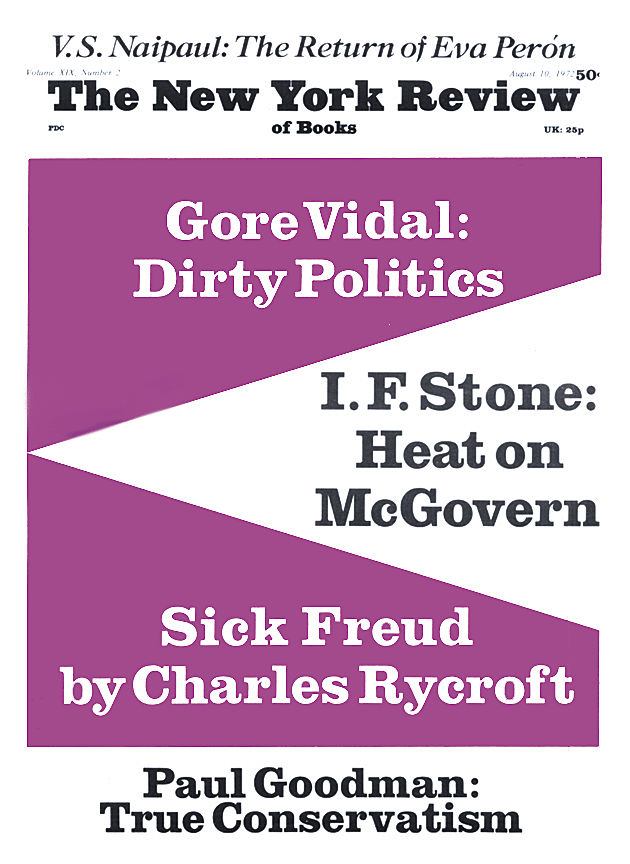

This Issue

August 10, 1972

-

1

Joseph Katz, The Poems of Stephen Crane (Cooper Union Publishers, 1966). ↩

-

2

Daniel G. Hoffman, The Poetry of Stephen Crane (Columbia University Press, 1957). ↩

-

3

Stephen Crane’s Love Letters to Nellie Crouse, edited by Edwin H. Cady and Lester G. Wells (Syracuse University Press, 1954). ↩

-

4

John Berryman, Stephen Crane (The American Men of Letters Series, William Sloane Associates, 1950). ↩

-

5

Quoted in R.W. Stallman, Stephen Crane, A Biography (Braziller, 1968). ↩

-

6

The Portable Stephen Crane, edited by Joseph Katz (Viking Press, 1969). ↩