In response to:

Father, Son, and Holy Ghost from the July 20, 1972 issue

To the Editors:

How well I remember the ghastly lunch mentioned by Mr. Karl Miller [NYR, July 20] at a franglais restaurant called the Etoile—in Soho, I would have said, not Bloomsbury. I had been invited by Mr. John Freeman, the editor of the New Statesman, whom I knew only as a back on television, and he brought with him young Mr. Karl Miller who was equally unknown to me, and (thank God!) my old friend, Pritchett. Poor Mr. Miller was suffering from a devastating cold. I had the impression that he had been dragged by his boss from bed, and I expressed very badly, and I’m sure unconvincingly, my sympathy for his predicament. It was really a terrible lunch—I don’t refer to the food. Freeman’s shyness equalled my own, and it was impossible to communicate at all with young Mr. Miller who could only sneeze and blow his nose and long, I felt sure, to return to bed. There was left only my friend Pritchett to talk to. Why had we been invited?

I describe this lunch because it must have fixed firmly in Mr. Miller’s mind the idea that I was not to be trusted. No one believes in the sympathy of a stranger—a base hypocrite he must have thought me. All the same he is wrong, in reviewing A Sort of Life, to be so mistrustful. I really did long to be finished with the lunch and to get him safely back to bed, just as my first memory really is of the dead dog in the pram, so why not say so? Nor can I see my error in mentioning that I paid for a Mass for my father with a sack of rice. Where is “the whiff of corruption”? Certainly there was no “thrill of clandestinity.” The whole affair was perfectly safe, and I mentioned it only to show the kindly character of the Irish priest who wanted rice for his poor Africans and not money for himself.

I have to protest rather more seriously when Mr. Miller, presumably on the strength of that one unfortunate meeting, pretends to know better than myself what I mean. “The casualness with which he tells the story of his life” (he means the first thirty years of it) “touches criminal negligence when he says: ‘With the approach of death I care less and less about religious truth.’ In fact, he means doctrine here not truth.”

But I don’t mean doctrine, I mean, as I wrote it, truth. Just as I did mean to convey genuine sympathy for that terrible cold of his at that traumatic lunch ten years or more ago.

Graham Greene

Paris

Karl Miller replies:

I am sorry I had a cold, and that Mr. Greene should denigrate a good restaurant, which lies, let’s say, somewhere between Bloomsbury and Soho. I can see that I have given offense, and I really wish I hadn’t, if Mr. Greene will believe me. I believe the context makes him mean doctrine rather than truth: either way, it would have been better if he had said more about the matter. The “whiff of corruption” came from his obtaining the rice “through my friendship with the Commissioner of Police.” I wasn’t suggesting that he was being untruthful, here or elsewhere: only that he was depending to excess on a particular set of effects. Incidentally, a misprint or act of God occurred to temper the description I gave of these effects. The sentence in question should have read: “The cryptic reference to the brothel is no more than a flashing of the Greene persona.”

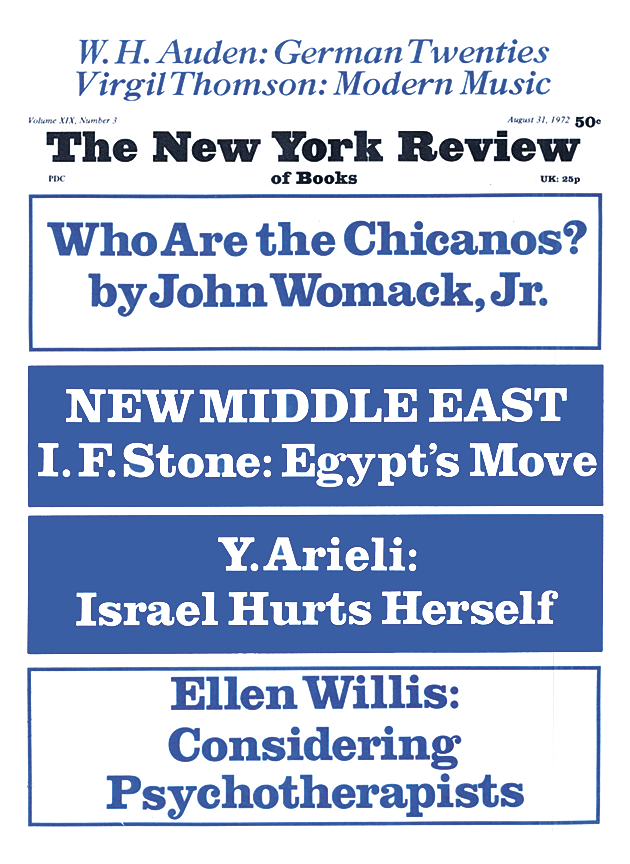

This Issue

August 31, 1972