1951

September 14. Venice. The Piazza at night is an opera set, with enough soldiers, beggars, ragazzi, lovers, lovers-for-money, to form a chorus of each. All that is missing, in fact, is a quality of music, for, whereas the gondoliers of the cinquecento improvised giustiniani to verses by Ariosto, today they imitate pop crooners, and with even wider tremolos.

1952

June 4. The Hague. Hotel des Indes. We attend the opening of the Holland Festival. Queen Juliana, ministers, ambassadors, generals: I have never seen so much pomp and so many medals, swords, epaulettes; the Stravs and I are the only guests not at least in evening clothes. At intermission, following Mozart’s K. 361—about half of it, rather, and that in wrong tempi—the Queen sends for I.S. to sit next to her, declares her admiration for his “works,” and is not only taken aback but speechless at his response: “And which of my works do you admire, Your Majesty?” The program ends with the Basler Concerto, in which nearly everything, including the relationships of tempi in the first movement, is wrong. Yet the conductor, Willem Van Otterloo, presented to I.S. afterward, asks how he liked the performance. I.S.: “Do you want a conventional answer or the truth?” (Van O. manfully opts for the latter, which is that it was “Horrible.”)

1957

August 28. Arriving at Venice shortly before noon we go directly to the outdoor restaurant at the Bauer. Thomas Beecham is there but does not see I.S. Nor does I.S. make himself known, for Sir Thomas is in mid-tantrum, apparently owing to an unsuccessful attempt to escape crème caramel. “I told you they have no tinned peaches in Italy,” he reminds his wife (and everyone else). “The maître d’hôtel is a nincompoop.” Our waiter complains, too—about the sirocco. “Tempo brutto,” he says, but, touching his parabolic commedia dell’arte nose, reports that this infallible barometer forecasts rain. I.S. orders a trout, which he flenses and disembowels as an ichthyologist might dissect a rare specimen.

It is Venetian washday Clotheslines cross the waterways and gondolas glide beneath sheets, shirts, dresses, tablecloths, trousers—except on the Grand Canal, which a police boat patrols against any unsightly display of laundry. In fact no sooner does a pink undergarment appear in a window opposite ours than the water cops speed to the scene and excoriate the offender with that lowest of all local imprecations, “Napolitana.”

1958

August 17. Venice. San Lazzaro degli Armeni. A French-speaking monk escorts us from the dock as bells peal and bearded brethren emerge from every direction and converge on the church. The service, that of the third day of The Assumption, includes the ritual eating of grapes. But if the sense of taste is satisfied, the others are not, for the incense chokes, the chanting is out of tune, the floor punishes the knees, and the pyrotechnical effect of a crescendo of candlelighting is spoiled at the climax by the addition of electric beams. We go to “Byron’s Room” afterward, where tea and rose marmalade are served by a femininely fussy monk who assures us that the scandalous poet’s writings are safely banned from the island. The windows here look over the gardens toward the casino on the Lido, only a short stretch of water but many long centuries away. Opening the door to depart, I.S. finds the entire brotherhood waiting to be photographed with him and to collect his autograph. Reputedly very learned, they are at the same time prepubertally childish.

From San Lazzaro we cross the lagoon to San Francesco del Deserto, now more than ever aptly named, for only fifteen friars remain. And no wonder. The island is an aviary, and the squawks, trills, twitters, hoots, warbles, boul-bouls (nightingales) are literally deafening. Most of these noisemakers are unseen, but a peacock parades the main pathway; and pigeons and plovers, swallows and “lecherous sparrows,” ouzels and owls (?—I am no birdwatcher) are visible in the trees and gardens, cloisters and eaves of the church. The human population is also in retreat in the shallows near the island, where birds shrilly protest as men in boots scrabble for scampi. The buoys here are shrines as well, which the fishermen supply with candles and adorn with flowers.

* * *

In the Campo San Bartolomeo tonight our thoughts are with Alessandro Piovesan, whose haunt this used to be. For Piovesan, ever late on his way to a crisis—underarm briefcase never containing the important papers he was always searching for in it—is now too early dead. At last year’s farewell dinner, when he proposed that dangerous toast “to next year,” my thoughts went to I.S. But it is Piovesan we mourn, and remember now, as we always will, by his own word: spirituale.

Advertisement

1959

September 7. We drive with Stephen Spender to Stratford to see Olivier’s Coriolanus. I had never before been so struck by the amatory language between Shakespeare’s soldiers. Thus Marcius to Cominius:

O let me clip ye

In arms as sound as when I wooed; in heart

As merry as when our nuptial day was done,

And tapers burned to bedward!

[They embrace]

And Aufidius to Marcius:

I loved the maid I married;…

But that I see thee here…

More dances my rapt heart

Than when I first my wedded mistress saw

Bestride my threshold.

And Menenius:

I tell thee, fellows,

Thy general is my lover.

Even the bully Coriolanus seems to prefer his soldiers to his wife, if not to his mother. Yet one does not entirely believe that “There’s no man in the world / More bound to’s mother,” partly because Coriolanus’ rhetoric about her borders on the comic—when, for example, he refers to her in Aufidius’ camp as “The honored mould / Wherein this trunk was formed.” But on this point the performance must be faulted, for the Volumnia is no lupine Roman matriarch, and Olivier overpowers her. Nor does the staging distinguish Romans and Volsci at all clearly, whereas the final scene is richly confusing, Coriolanus dying not in the Volscian city but on the Tarpeian rock.

At 3 AM, back in London, drinking claret at Spender’s, I.S. brings up Eliot’s remark at dinner last night to the effect that Shakespeare was obviously more concerned with Coriolanus the play than with its poetry. But the weaknesses of the play, its unlikable hero foremost among them, almost sink it. Yet consider some of the poetry:

Break ope the locks o’ the Senate and bring in

The crows to peck the eagles.

September 20. Venice. Nicolas Nabokov for lunch. Talk about Alban Berg. I.S.: “To me, Berg’s music is like a woman about whom one says, ‘How beautiful she must have been when she was young.’ ”

It is Sunday, which is ideal for church visiting since they are all open and all deserted. We go to San Zan Degolà, where bells warn the nuns to beware the tempting sight of I.S. and myself; to the Gesuiti, where the weeds are so thick around the gesturing Baroque saints on the pediment that they might be performing a ballet in a field; and to San Salvatore, where the confessional might have been designed for a maximum security prison, priest and penitent, like prisoner and lawyer, being obliged to talk through a grille; except that this is cruciform and white—in all but the center, which is extremely dirty, no doubt from the contents of the confessions. Near the church is a pet shop and in its window a trapeze on which a score of lovebirds crowd each other like kabob on a skewer.

* * *

I.S., reading Millard Meiss’s Mantegna As Illuminator, has come across an account of the Venetian Senate voting to sponsor a scheme to poison the Duke of Milan. One imagines such vendettas to have been ordered in secret, however, probably by a chief of police. That they were decided upon democratically seems even more heinous.

October 10. At the Zanipolo this morning we compare a color reproduction of the Widener Canaletto with the same view recorded by I.S.’s camera in April, 1931. He and V. had come from Trieste by seaplane then, partly to visit Diaghilev’s grave—as yet without a stone—which I.S. photographed as well.

The most obvious difference between the Canaletto and 1931 (or now) is in the destruction—and very poor restoration—of the canal-front houses. Other than that, the gondolas in the painting have felzi and are flat (not crescent-shaped), and the gondoliers wear red bloomers and red fezzes (are they from the Fondaco dei Turchi?).* A wellhead on the Campo side of the Ponte Cavallo has disappeared and so has a wooden bridge near the Mendicanti. On the other hand, the Colleoni monument has acquired a fence. Less conspicuously, the façade of the Zanipolo seems to contain more paterae now, and it definitely does contain two more sarcophagi in the arcades. Apart from that the scarred and mottled epidermis of the church is much the same, and less faded, sun-bleached, wind-worn than the other buildings. But in the painting the Campo is pleasingly mossy and almost the same green as the canal, which is a lutulent open sewer now for people who, to quote the psalmist (but with another meaning), “do their business in water.”

Yet the decline from the century of Verrocchio to that of Canaletto is as great as that from Canaletto to our own. And the most convenient measure of it is in the painter’s treatment of the equestrian monument itself. For he loses the city’s most powerful human image in the dark windows and shadowed bays of the church, entrusting the evocation of former magnificenza to the pedestal alone. The effect is only slightly removed from that of a Chirico statue-in-an-empty-square.

Advertisement

Nor is the eighteenth-century Campo exactly bustling: two marketers with baskets; some idlers and onlookers; a pair of mantilla-ed churchgoers; a masked man; a man and woman in black (he a prothonotary or procurator, to judge from his wig, she a widow perhaps but if so a merry one, being veil-less and décolleté). The only other figures are two tourists, those most ominous of all portents of decline; or so I take them to be, for one of them points “appreciatively” to a feature of the church. A puppet booth appears to be setting up in front of the Scuola, but this part of the picture is clearer in the Dresden version of it, which also exposes a Gainsboroughblue curtain across the door of the Zanipolo. Yet what was the painter’s perspective? Did he use the camera obscura? He could hardly have been on the next bridge, that view being blocked by buildings, as Bellotto’s Scuola di San Marco, in the Academy, attests. Which leaves fantasy, the perspective of Marieschi’s engravings.

* * *

A footnote to Ruskin. The smells of Venice: stagnant canals and the lagoon at low tide (sulfurous); exhausts of motoscaffi and vaporetti (like a World War I gas attack); urine (especially acrid in dark alleys in early morning, at which time they are a pis aller); excrement (dogs’, an impasto on the more crowded pavements); the stench (and inky obnubilation) from the oil refineries at Mestre; the reek of drying fish nets in front of the Arsenale (one of them ignominiously draping a stone lion, part of Morosini’s Greek booty and already well abused by Harald of Norway’s Kilroy-type inscription during a Byzantine war six centuries earlier). Cooking odors everywhere are saturated by frittura di pesce (nauseating), but the Erberia stinks preponderantly of cabbage, the Merceria of coffee, the Fondamenta del Vin of vinegar. Yet the whole city is pleasantly fragrant after rain. Interiors exude dankness (even clean bed linen is dank-smelling), mustiness, and decay, while churches are redolent of incense, altar flowers (sickishly sweet with tuberoses), and, just possibly—it is the rarest of emanations—the odor of sanctity. In 1438, according to the Catalonian traveler Pero Tafur, scented bonfires fumigated the city and deodorized the canals. Which may be history’s first operation aerosol.

Venetians themselves are strongly aromatic, some from infrequent bathing, some from perfumes (patchouli is favored by elderly females, barbers’ pomades by middle-aged males), some from garlic and chianti—a halitosis corrosive enough to peel paint. I.S. compares these noxious exhalations to “acetylene,” and perhaps they are inflammable and the more grossly afflicted will someday ignite and begin to breathe fire like demons in Dante.

Colors cannot be described, or even accurately evoked through comparisons. Thus one could say that when the tide is out, the “ring” of the city—in the sense of the “ring” in an emptied bathtub—is spinach green. But it would be better to say algae green in the first place, and that changes with every passing cloud. I.S. says that the primary Venetian “color” is black—gondola black, the black of the Virgin in the Scalzi, of the Christ in Santa Sofia (with gold breechclout), of the wooden Moors (those eighteenth-century Venetian cigar-store Indians). But I.S. does prefer the black-and-white Venice to the polychromatic one, and of all Venetian “landscapes with figures,” that of Santa Maria della Salute with foreground of black-cassocked priests.

Venice is an ingrown, self-reflecting city, hence a city of mirrors (it even has a “calle dei specchieri“) of which the largest is the lagoon. It is also a maker of glass, and of all its glasswares—cut, incised, engraved, frosted, gilded, tinted—the most beautiful are two azure ottocento candelabri in the Scalzi, and the violet ampullar lamps in the arcade at Florian’s. Venetian occupations are no less ingrown: women in tiny island worlds still make point lace, as centuries ago men carved quatrefoil. And Venetian love is ingrown, a world capital of pederasty. (“Blowing in Murano” says an advertisement in the Frezzeria. But surely not only there.)

1972

April 10. We drive from Rome—hardly visible beneath election posters (“Vota Liberale,” “Vota Communista“) and advertisements for the Banco di Santo Spirito—to the Manzù museum at Campo Fico, where our cicerone is the sculptor’s model, Inge. So many of the maestro’s figures are of the nude Inge herself, however, that it is practically impossible, if impolite, to refrain from mentally undressing the original. In fact Manzù’s world centers so closely on Inge—straying to any large extent only to natures mortes, helmets (an obsession about headgear), priests and their raiment—that one looks for her features in all of his women, including the female partners in two tempestuous copulations in bronze. But the half of the museum devoted to theatrical designs is more revealing of the artist as a whole. Whereas the sets—friezes exploiting pleated drapery in the same way as the sculptures—are generally successful, the costumes are often naïve. But Manzù is naïve, in Schiller’s sense, a naïve of genius, as at least one of the costumes, that of the Devil in Histoire du soldat, shows: the fallen angel has a tattered black wing, and he wears a fig leaf of solid gold.

The gate to the artist’s hilltop home still threatens intruders with canine dismemberment, but the hounds are nowhere in evidence (bite each other and die of rabies?), and the barbed wire is less obviously dangerous now than the cactus. The maestro greets us outside, against a landscape as undulant as the flanks and fesses he loves to sculpt, for Manzù is an “old man mad about hills.”

His studio could serve as a B-52 hangar, yet is not tall enough to shelter a mammoth opus-in-progress that stands just outside the entrance as mysteriously as the Trojan horse. Whatever it is, the scaffolding and canvas covering suggest that the sculptor has struck oil and that he prefers to keep it secret. What the studio does contain are plaster nudes; mitred heads, both in relief and in the round, the latter including two of Pappa Giovanni; numerous drawings; three dolls’-house-like models of a set for the Berlin Opera Elektra; and, oddly, a clump of Winterhalter-period trumpets and hunting horns, tied to the wall like dead game—yet not oddly at all, as one looks a second time at the instruments’ rounded tubing, flared bells, female curves.

The bozzetto of I.S.’s tomb is a flat oblong block, actual size, set in a trough-like frame, later to be covered with porphyry. The sculptor brings out a piece of the milky marble of his choice, but asks V. to decide between lapis lazuli and a light green stone for the lettering. “Blue was our color,” she says, but the green is in any case unsuitably veined. He draws the cross, which is to be encrusted at the head of the stone, on a square sheet of gold—at high speed, in contrast to the way he writes, which is like a backward child. In fact he succeeds in writing the difficult word “Stravinsky” at all only thanks to Luisella, his American-speaking secretary (her favorite comment: “He’s not kidding”) who somehow pulls him through, though the outcome for a time is in doubt. (V. wants to be certain he does not make a “w” of the fifth letter, which is the German spelling, and an “i” of the final one, which is the Polish.)

He promises that the “pietra” will be in Venice by June for the “sistemazione” and tells V. that he wishes to make a gift not only of his art but of the materials. Then, as we leave: “I would like to have made something that could last as long as Stravinsky’s music, but stone, which won’t, is all I have.”

April 11. An advertisement on the Via Flaminia for the forthcoming exhibition of Henry Moore in Florence. But at least the viewer will be able to see the Tuscan landscape through the holes.

During the drive to Venice I am obsessed by the thought that I.S. is happy V. is coming, just as he used to be when she returned from a drive in Hollywood. Our arrival is an unbearably empty homecoming, therefore, made all the more depressing by an unseasonable inundation: half of the Piazza is submerged and the Molo is impassable. Venice is dying on its feet (fins?).

April 13. The Archimandrite—in mufti: black suit, black shirt, gold cross on a gold neck chain—comes to discuss Saturday’s Panikhida (Greek) service. He says that three crosses scrawled with signatures have been stolen from the grave by souvenir hunters, but that the mayor has now had a plaque cemented to the wall behind it. Apart from Greek, however, the Archimandrite’s only language is the Venetian dialect, and conversation is limited.

April 14. The high waters having receded, we go to the cemetery, where a transformation has taken place. In the midst of death we are in life. The secluded corner is a five-star tourist attraction now, and arrow-shaped STRAVINSCKY (sic) signs direct the traffic. Business at the florist’s has doubled, the postcard stall is sold out, and the ortodosso wing, I.S.’s part of it anyway, has actually been weeded. Above all, the rather surly gardeners of last summer have become obliging receptionists, proud, like the gravediggers—who seem to have taken an entirely new lease on death—of the new-found importance of their island.

Passing the tightly packed, pectinate tombs of the poor, my thoughts turn to excarnation; “A bracelet of bright hair about the bone”; to “dogsbody” and “nobodaddy”; and to the likelihood of “God” versus the likelihood of accidents and chains of events leading over millions of years from amino acid in volcanic lava to Stravinsky; and more concretely, to the underlying attraction of cemeteries, which may simply be in the answer they offer to the pretense of equality in the institutions on this side: namely that rich and poor, great and humble, are alike; for in San Michele, at least, apart from the price of the name plate and memento mori, they are alike. Thus “God” is an invention before which, at last rather than at first, we can be equal.

It is Easter Week in the Eastern Church, and many of the graves, including I.S.’s, have lighted candles. Placing her flowers on the still tombless ground, V. says: “I am unable to believe it even now, except that the marker says so” (“Stravinsky, Igor” in black paint on the mayor’s plaque). Just then a loudspeaker—“ATTENZIONE, ATTENZIONE,” as the word sounds in airports and railroad stations—startles us. “Quattro spiriti sono….” But the disembodied voice is interrupted by static—supernal, no doubt—until the final words, “al porto principale.” Apparently workmen are being summoned to receive four newly arrived coffins—unless four escapees have been discovered, and the authorities are trying to close all exits including resurrection.

April 15. The Panikhida this morning begins in “San Zorza” (Saint George of the Greeks) and ends, an hour and a half later, at the grave side. In the church, we stand, with Nicolas Nabokov, before a laurel wreath on a table covered with red cloth (the “Red Table” of Les Noces!), which is in the same position in the bema where the bier had been in the Zanipolo a year ago. Small golden balls, like the silver rattles of the censer, are attached to the wreath. (Are they related to the golden balls, clustered like stars in the firmament, on the domes of San Marco and of the Zanipolo?) On either side and beyond the table are tall candelabri and silver lamps on silver chains.

Much of the service, which includes a Mass, takes place behind the iconostasis, some of it visible through the open center door, some merely audible. It begins with a procession (vkhod) through the iconostasis into the church. A server carrying a tall candle enters through the right door, a deacon enters through the left and proceeds to an analogion from which he sings the responses, and the Archimandrite—bareheaded, in vestments of brocaded gold—enters through the center, censing the church. He then returns to the altar and begins a chant—and in that instant the day a year ago is brought back. The music is unornamented at first, apart from cadential échappées. At times the deacon, in a hollow voice, joins in an octave below. The high point occurs when the Archimandrite again descends to the center of the bema, lifts the great red book of the Gospel to his forehead, for our veneration, then turns to the altar and in a radiant voice sings a verse from St. John. At the end, he dons his black-crape-like Klobook—another reminder of a year ago—and places a piece of the antidoron in V.’s cupped hands.

On San Michele, the deacon shakes smoke over the grave after which the Archimandrite lays the laurel wreath on its head and sings a prayer (“sophia,” “makarios“). As it was a year ago, the most painful moment is when he invokes the name “Igor.”

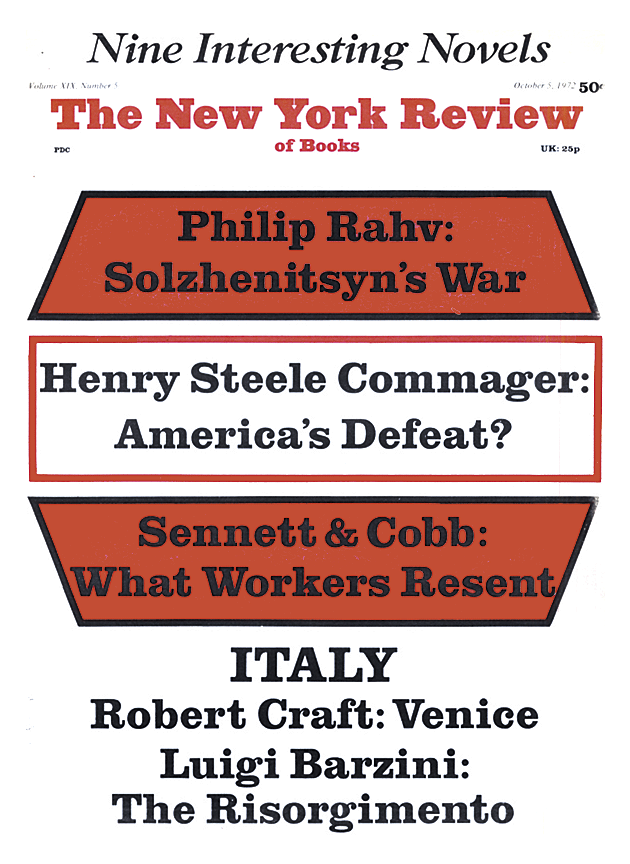

This Issue

October 5, 1972

-

*

I was unaware at this time that the present gondolier uniform was regulated by ordinance at a much later date.(R.C., 1972) ↩