This collaboration between a writer and a photographer should have one title, not two. How can we be expected to go into a bookshop and order both? So I rechristen it Peter Matthiessen and Eliot Porter, The African Experience (for that is what it is). The two men work hand in glove. Each is a master and I do most warmly recommend their joint product. There have been several outstanding books of photographs of the game reserves, but Mr. Matthiessen has written an admirable text, accurate, original, scientific, and moving.

I have met many of the same people and written about the same places, and I can only say that after reading Mr. Matthiessen’s accounts of them I wish I had seen more of the flamboyant fearless young elephant watcher, Iain Douglas-Hamilton, or the white hunter turned game warden, Myles Turner. Also of Desmond Vesey-FitzGerald. Add Sandy Field and Hugh Lamprey of the Serengeti, John Owen, John Williams (birds), and Roger Wheatear, formerly of the Uganda parks, and you have a group of dedicated, high-powered naturalist administrators hardly to be matched anywhere. To rule a wild animal reserve as big as a large county, to fly one’s own plane over it, controlling its police and rangers, working on some special subject in its laboratories, and to be part civil servant, part naturalist, part brigadier and guerrilla leader, dealing peremptorily with floods, poachers, bandits, fires, ambushes, and mad elephants is one of the last careers left for those who wish to integrate mind and body, thought and action into something like a complete man.

Few who write about East Africa will face the truth, though Mr. Matthiessen drops many hints. It can be stated in three propositions:

- The game lands of East Africa, particularly the national parks of Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania, constitute an area unique in the world both for natural beauty and for the wealth of fauna that can be observed in conditions approaching the terrestrial paradise before the coming of man.

- With the destruction of their habitat by agriculture, of the animals themselves by hunters, poachers, and disease, civilization is making away with all the large animals outside these areas (except the Kruger). Elephant, lion, leopard, rhino, hippo, giraffe, buffalo, gorilla, chimpanzee, and many antelopes simply don’t exist outside them or will shortly disappear.

- But the animals inside the parks are doomed also, victims of the relentless pressures of the population explosion, the demands of the natives, the activities of mechanized poachers or political bosses. Most Africans don’t want animals, they want the land for their people. To persuade the African to love his animals or the wilderness from which he has emerged is difficult; and to convince him that they are required for tourism and that tourism is a better source of income than agriculture is even more difficult. Nothing can save the large animals and their habitat but summary laws like those by which William Rufus preserved the New Forest, or compulsory birth control for all hominids, or some great man-made disaster, atomic or bacterial. It is not enough to believe that the cause of science is furthered by the preservation of wildlife, or that we owe a debt to posterity to preserve for it the world in which we found ourselves, or that we need the wilderness for therapeutic purposes. The wilderness can only be maintained by leaders who believe that animals can matter more than man and must be reinstated.

President Nyerere of Tanzania is the only head of state to have a glimmer of real sympathy for the animals, although the cut in British subsidies has gravely affected the welfare of the white park superintendents. The situation is becoming acute in Uganda through a breakdown, even though temporary, of the tourist traffic that keeps the parks going. In the Congo there have been many losses, though the great Parc Albert is not one of them. The Kenya outlook is still hopeful thanks to enlightened African civil servants, though each park still has many problems.

Even while we leaf through the wonderful photographs in this book, the way of life they preserve is being eroded. Many of us may never get any closer to these animals than through Mr. Porter’s pictures or Mr. Matthiessen’s observations. I remember a retired parks chief in Nairobi telling me how much he dreaded the sight of an African shamba, a hut with its family and crop of maize, appearing from nowhere to presage the infiltration of yet another corner of his territory, more lethal than the poachers’ wire or bush fires.

Another vicious circle arises from the need to provide more hotels and transport for more tourists so as to extract still more revenue. The hotels will make a Costa Brava out of Lake Manyara, a Las Vegas in the Serengeti with an airstrip in every crater—and for half the year will lie idle. There is also the damage done to the habitat by the animals themselves as increasing herds of hippo destroy the river banks, and elephants, congregating into the animal sanctuaries like refugees, tear down the trees which protect the soil and yield their foodstuffs.

All flesh is grass, and all grass is flesh in the Serengeti region of Tanzania, where the great herds of wildebeest, gazelle, and zebra seem infinitely renewable, yet a perpetual carnage is proceeding. To the aesthete these lands are a series of frescoes of the terrestrial paradise. The pachyderms provide one kind of beauty, the carnivores another, the grazers a third—all set in the blue-green prairies of the Serengeti, watched over by distant volcanoes, or on Lake Edward beside Ruirwenzori and the mountains of the Congo. The baobab trees and acacias, the forests, the lakes harbor an incredible bird population—the kori bustard, the heaviest bird that flies; the fish-eagles; kingfishers; waterfowl, flamingos and pelicans and giant herons; the painted touracos in the forest and the small tree animals; the hyraxes, colobus monkeys, pangolins.

But the aesthete is wrong. This is not a static Eden. Imagine a visit to a picture gallery where one gazes on a battle scene by Uccello, a Rembrandt self-portrait, some conversation pieces, still lifes, hunting scenes, or mythological tableaux. Suddenly the battle comes to life: blood flows, heads roll, armor clashes; the still lifes putrefy, the self-portraits defecate loudly, the hunters wound and maim, and the gods and goddesses copulate indiscriminately; the stench rises and vultures materialize to bury their bald necks in the corpses. Such is nature in the wild and so it must appear to civilized Africans who cannot appreciate our passion for it. Lions are stupid, elephants destructive, leopards and buffalo dangerous, crocodiles a menace. Fever, sleeping sickness, anthrax, and bilharziasis protect nature’s realm, policed by the hyena and the marabou stork. As Mr. Matthiessen writes,

Advertisement

Vulture and marabou in thousands had cleared the skies to accumulate at the feast. These legions of great greedy-beaked birds could soon drive off any intruder, but they are satisfied to squabble filthily among themselves; the vulture worms its long naked neck deep into the putrescence, and comes up, dripping, to drive off its kin with awful hisses. The marabou stork, waiting its turn, sulks to one side, the great black teardrop of its back the very essence of morbidity distilled…. It takes to the air with a hollow wing thrash, like a blowing shroud, and a horrid hollow clacking of the great bill that can punch through tough hide and lay open carcasses that resist the hooks of the hunched vultures. Vultures fly with a more pounding beat, and the cacophony of both, departing carrion, is an ancient sound of Africa, and an inspiring reminder of mortality.

Mr. Matthiessen loves primitive man as well as animals. He turns up at Richard Leakey’s digs on Lake Rudolf, which were later to yield such spectacular results. He maps the disappearing tribes who were ousted by the Bantu as well as the white man: the little people who live by hunting or use a click language; the Hadza of the half-explored Yaida valley, the Dorobo who find honey with the ratel and honey guide bird (indicator indicator), the Rendille, the Pygmies of the Ituri Forest. He is also to be trusted for the correct names of plants and flowers.

Much time in the game parks is spent in waiting, if waiting is the right word for that state of creative expectancy when a pungent smell can be elephant or ocimum, a broken twig an insect or a python, and the liquid note of the tropical boubou like the bird in Siegfried. I suppose what most aesthetes on safari secretly hope for is a confrontation ending in friendship like that of Androcles and the lion. There are moments when one feels such love and well-being that it seems inconceivable that the animals cannot recognize one’s devotion to them. The crocodile, our authors tell us, cannot resist the nasal call (one nostril stopped) of “im im im”—but crocodiles are nearly extinct, like the dugong and the turtle, the bongo and the golden cat. “Africa. Noon. The hot still waiting air. A hornbill, gnats, the green hills in the distance, weaving away west towards Lake Victoria.”

Like myself, Mr. Matthiessen is an elephant man, although there is so far no visa for elephants, no noise, no smell, no offering that is a passport to their friendship. They scream and trumpet at friend and foe alike, one of the few creatures to reach old age in the wild—“the rumbling of elephant guts, the deepest sound made by any animal on earth except the whale.” Like myself, Mr. Matthiessen found himself involved in the great dispute about culling elephants at Tsavo Park (“Culling no murder”). The elephants had multiplied vastly in this enormous park and, as at the Murchison Falls Park and the Ruaha Park, were destroying their habitat by ringing all the trees. Whether this forms part of some rotation system by which the elephants benefit from converting forest to scrub and scrub to grassland is not clear. The grass is so liable to fires, often started by poachers, that the herds are the losers. The problem was therefore whether to crop the herds as was done to the hippos on Lake Edward or at the Murchison, or to allow nature and elephant sagacity to sort the matter out.

Where food is scarce elephants appear to gestate later than elsewhere. The warden of Tsavo East, David Sheldrick, led the laissez-faire school, apparently with support from his overseers in the Ministry and the Ford Foundation. His opponent was Dr. Richard Laws, head of the Tsavo Research Project, with his team of biologists, one of whom was a youthful iconoclast, Gordon Watson, like a scientist in a Huxley novel. Dr. Laws was most impressive and had done much work in the Arctic; he was keenly interested in polar bears’ livers and the excretion by which hippos protect their skins from the sun. He was backed up by Ian Parker, whose Wildlife Service (Nairobi) did all the shooting.

Dr. Laws was convinced that heavy cropping would protect the survivors from death by starvation. Behind the dispute lay the hostility between oldtime park wardens and conservationists, working a lifetime among animals, and biologists, “clever young men from the universities,” who came out with their laboratory statistics and theories. “The Tsavo elephant problem is a classical example of indecision, vacillation and mismanagement,” wrote Dr. Laws recently. General conclusion: something will have to be done.

Advertisement

The first lion I saw at close quarters, on a rock in the Serengeti, was in company with Dr. George Schaller (the gorilla expert) and Dr. Lamprey. I was impressed until Dr. Schaller said, “That’s one of mine. You’ll see one of my disks behind his ear.” By then he had taken a census of most of the lions in the Serengeti: Mr. Matthiessen has some pleasing anecdotes about this “lean intent young man” whose Serengeti Lion is the result of his concentrated labor. It is a specialized book which will appeal primarily to scientists, biologists, ecologists, and zoologists, but is also of interest to the layman and full of remarkable photographs of lions playing, killing, and making love. It is, I think, the antidote to Elsa.

Lions seem dull because, like cats, they spend so much of their time at rest, but they are far more intelligent than cats and prodigiously strong. As with elephants, responsibility develops with the female. Dr. Schaller analyzes the lions’ roar and other sounds and describes their sex lives. The king of beasts can pack two or three hundred orgasms into a weekend, at first with several mates but finally drifting into monogamy for the last hundred. The copulations are brief and terminate with a growl and a cuff. “George,” as Peter Matthiessen writes, “is a stern pragmatist; he takes a hard-eyed look at almost everything.”

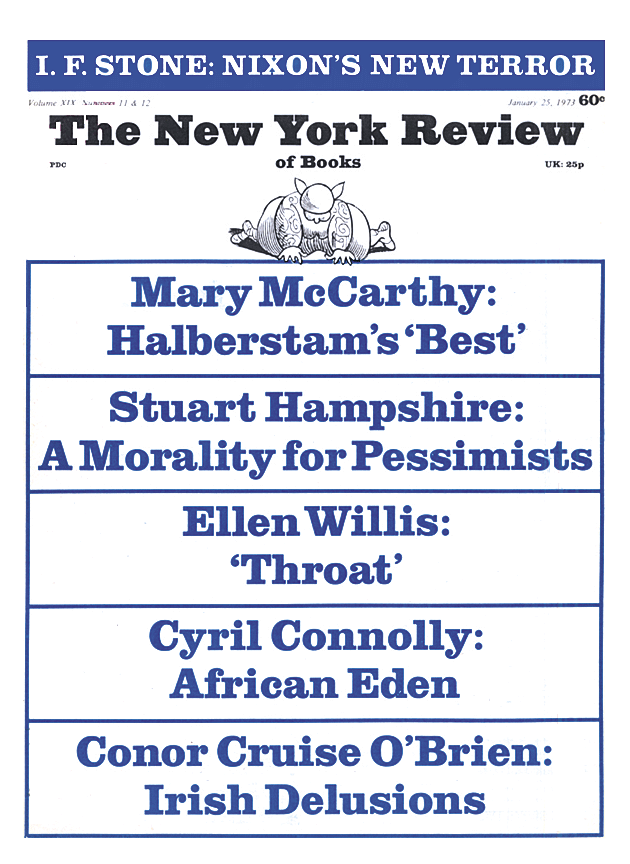

This Issue

January 25, 1973