The major pleasure of old age lies in the ruthless one of remembering. It is notorious that Max Beerbohm plumped for this very young, possibly because advertising was coming in and he chose impertinent humility as his line; but for other reasons memory rapidly became a principle. In the 1890s he went firmly back to a sly eulogy of George IV because of that monarch’s wardrobe, and also proposed a return to cosmetics. Since the Regency the English had, he noted, exchanged the masks of rouge for the natural lobsterishness of vulgar Nature: the flesh had had its innings. Now was the time for reviving time-defying artifice. The romantics, no doubt because of the exhaustion caused by their reckless psychological insights, the bourgeoisie because of the glow of their moral satisfactions had begun to think of masks. The point was quickly seized by Max at the age of eighteen. So quickly that Wilde, already alarmed by the rise of a modish younger generation, asked a lady whether Max ever took off his face to reveal the mask beneath.

Yeats and others were to write of the mask as being the mark of the artist, so these words of Wilde’s were not an example of paradox for paradox’s sake. They contained a truth: Max Beerbohm had no face. Or if he did have one, it was as disponible as an actor’s. He was, in this sense, ancient man, or, rather, ancient child. Dressed in top hat and swallow-tail coat, with heavy eyebrows and unflickering eyes (in which get-up he had probably been wheeled in his pram in Kensington Gardens when he was not in the nursery considering himself in the mirror), he was armed to meet the human race.

The pose was not totally original. After all, there was already a cult of middle age and indeed of old age among the English, and among the Europeans, of the nineteenth century. Darwin had made the human species suddenly far older than the orthodox 4,400 years; but somehow the survival of the fittest had come to mean “naturally,” and not aesthetically, elegantly, or critically, the fittest. When Max was growing up, the Prince of Wales looked like a licentious grocer on a spree in “gay Paree”; only Ruskin, the son of a successful sherry merchant, looked like a saint. Beerbohm did not choose to be a saint—there was the family connection with the theater—but he did lean to that dandyism which the English had exported to France after the Napoleonic wars and which, under the influence of Baudelaire, had been darkly reimported into artistic England.

One had to be a very singularly old young man to bring it off and to have a doctrine to play with—play because the English were given to games, histrionics, hoaxes, impersonations, and to turning the conventions they loved into a sophisticated indoor sport. Here Beerbohm had the advantage of not being, in the strict sense, English. He was born and educated in England, but his parents were, I think, Baltic Germans of the fanciful kind: his father was the kind of man who was amiably slack as a father-figure. The mother had a delightful difficulty with English idiom and would say things like, “I feel as old as any hills”—a remark that would have stimulated the spirit of detachment from the norm in any family.

Max Beerbohm’s pose was therefore both foreign and ancient: he was the expectant dapper blank on which anything might be inscribed. If he had a personal secret it was terrific will. People, for this inhuman creature, would be visible objects. The sociable influence would come from locking himself into an applauded set and assuming that it would last forever. But in 1910, when Edwardian London was done for—war coming on, the flaunting of Big Business and Big Labor, the rise of press lords, the invention of advertising, socially pushing rich Americans—he resigned, married an American actress, and vanished for the rest of his life to Rapallo. He had seen the disaster coming in the Boer War, in John Bull’s horrible behavior, in Kipling’s terrible chin. The decadence was in society and not in art. London had become provincial when comfortable soft hats came in, and off he went, like so many of the English, to his Italian suburb and years of silence. The only time I ever met him, in his real old age, he mentioned nostalgically as we walked across the foyer of an expensive hotel that in his time it had been improper to remove one’s hat in such deplorably public premises.

Beerbohm was born in London. His expatriate and privileged parents must have disposed of a lot of moral luggage, and had left him to travel light on talent alone. He was exactly the kind of foreign pearl required to irritate the placid London oyster. And he appeared at the right time. The fact that his brother was a world-famous actor twenty years older than himself aroused the competitive spirit in the best possible way: if Beerbohm Tree had the art of being tall, his brother could be deadly by making himself smaller and smaller.

Advertisement

And then—to put aside for the moment such matters as the acquaintance with Wilde and Beardsley, the fading pre-Raphaelites, and the last remorses of the Romantic Agony—it was the moment for wits. London had many clever newspapers and reviews; the theater had Shaw and Ibsen to deal with, Pinero and others to insult. The city was the paradise of the passing essayist. Wilde and Beardsley were a gift to that kind of light, fantastic comedy in which English talents have always excelled. The amount of theater criticism and essay writing that poured out from Max is remarkable. Perhaps it was his half-foreign eye that made him also a caricaturist, a mimic, and the finest parodist we have ever had.

Those who have suggested that his enigmatic loneliness was due to fear of homosexual tendencies and of being found out as a secret Jew are (I am as sure as one can be) wrong. There is no evidence of hidden Jewishness, in spite of what Ezra Pound asserted. As for homosexuality, he was horrified by the scandalous intimacies of the flesh; his sexual temperature was low. He was the complete narcissistic child—as his innumerable caricatures of himself show—who had not even attained the narcissism of adolescence, but sat with the scrupulous prudence of the demure child in front of any mirror he could find, experimenting in poses and grimaces.

He lived by the eye and—as one can see by his drawings—discreetly beyond touch of hand. Two caretaking wives looked after him in middle and late life and—to all appearance—treated him tenderly if overwhelmingly, as a dangerous toy. And then—how typical this is of an intelligent and sensitive man who is without roots—he turned to literature and the arts for his nationality. Among other things, in the wide-eyed persona he invented, there is sadness. Was it the sadness of not being a genius on the great scale, like his admired Henry James? Possibly. Was it the sadness of knowing that his work must be perfect—as that of minor writers has to be—because fate made him a simulacrum? Or was he simply born sad?

And now to Beerbohm’s centenary year in times that are so unsuited to him. Piously Rupert Hart-Davis has done a large catalogue of all Beer-bohm’s caricatures that have been framed or suitably reproduced, a volume useful to collectors. (It is amusing that Beerbohm’s devastating caricatures of Edward VII and George V, done in his “black” period, are among the treasure in Windsor Castle.) A selection of essays, A Peep into the Past, has also been made by Hart-Davis, and serves to show the development of the essayist. In later essays the charm has become benign and thin, but three of them are excellent: the remarkable spoof portrait of Wilde done when Beerbohm was still an undergraduate and suppressed after the trial, in which occur the well-known lines:

As I was ushered into the little study, I fancied that I heard the quickly receding frou-frou of tweed trousers, but my host I found reclining, hale and hearty, though a little dishevelled upon the sofa.

The other, written on De Profundis, denies the comforting view of many English critics of the time that Wilde had undergone a spiritual change after his imprisonment. Beerbohm saw him as still an actor but with a new role.

Yet lo! he was unchanged. He was still precisely himself. He was still playing with ideas, playing with emotions. “There is only one thing left for me now,” he writes, “absolute humility.” And about humility he writes many beautiful and true things. And, doubtless, while he wrote them, he had the sensation of humility. Humble he was not.

And there is the hilarious pretense in another essay that a powerful bad poet of the period—Clement Shorter—has spent his life writing love poems not to a lady but to one of the awful English seaside resorts.

The best American essay on him, in my opinion, was by Edmund Wilson, dry and to the point. There was no mellifluous English nonsense about the “inimitable” and “incomparable.” I feared what would happen to Max if he was put through the American academic mangle. There seems to be a convention that this machine must begin by stunning its victim with the obvious, and when I found Mr. Felstiner saying in his study The Lies of Art about the notorious essay on cosmetics that, “Cosmetics were a perfect choice to join the teachings of the moment, aestheticism and decadence,” I understood what Max meant when he said that exhaustive accounts of the period “would need far less brilliant pens than mine.” But, as I went on, I found Mr. Felstiner a thorough, thoughtful, and independent analyst of Max as a caricaturist and parodist. He has good things to say about Beerbohm’s phases as an artist in line and water color, about his absolute reliance on the eye. He is admirable on the parodies in which Max reached the complete fulfillment of his gifts, and his comments on Zuleika Dobson are the most searching I have ever read.

Advertisement

Beerbohm caricatured Americans, the working class and the bourgeoisie automatically as part of the impending degradation of civilization and the arts…. John Bull is the crucial figure throughout, shaming himself in Europe, vilely drunk or helpless in the face of British losses, and deeply Philistine. On the evidence of these cartoons, Shaw called Beerbohm “the most savage Radical caricaturist since Gillray.”

His Prince of Wales is a coarse, tweedy brute, imagining a nunnery is a brothel. His pictures of royalty were savage.

What angered Beerbohm during the Boer War was not Britain’s damaged empire—he was indifferent to that: “the only feeling that our Colonies inspire in me is a determination not to visit them.” It was the self-delusions and debasement of conduct at home, the slavish reliance on grandiose national myths.

But he was really no Gillray or Grosz. He

…enjoyed with an eye for what men are individually—for their conceits, contradictions, deadlocks, excesses. Beerbohm drew more for fun than in the hope of changing attitudes or behavior. In fact he depended as man and artist on the survival of the context he satirized.

Edwardian literature has many, many sad stories, stories whose frivolity half discloses the price a culture is paying for its manners and illusions. Zuleika Dobson is one of the funniest and most lyrical and sad. As in all Beerbohm’s fantasies, literary cross references are rich, graceful, and malign. Fantasy states what realism will obscure or bungle:

Yet in comparison with previous jocular or sentimental treatments, he could claim to have given “a truer picture of undergraduate life.” His book points to real elements of conformity and sexual repression…. By chance the river itself has the name of Isis, Egypt’s greatest goddess, all things to all men. So what emerges is an allegory of Youth forsaking Alma Mater, the Benign Mother, for the consummating love of Woman.

Zuleika seems to have been modeled in part on the famous bareback rider whom Swinburne knew, and she has a close connection with “the Romantic Agony.” She is a “Volpone of a self-conceit; her mirror is the world,” i.e., she is the male dandy’s opposite number. Mr. Felstiner writes of her rapture when she is spurned by the Duke:

All the world’s youth is prostrate with love but she can only love a man who will spurn her…. “I had longed for it, but I had never guessed how wonderfully wonderful it was. It came to me. I shuddered and wavered like a fountain in the wind”—sounds like the joys of flagellation. The Duke even finds himself wanting to “flay” her with Juvenalian verses. “He would make Woman (as he called Zuleika) writhe.”

The element of parody ensures the tale: Beerbohm’s excellence and his safety as an artist are guaranteed because, unfailingly, he is writing literature within literature. Parody, as Mr. Felstiner again puts it, is a filter. It drains both literature and life.

Beerbohm rarely drew from photographs. He drew from memory. The recipe for caricature was, “The whole man must be melted down in a crucible, and then, from the solution, fashioned anew. Nothing will be lost but no particle will be as it was before.” So Balfour’s sloping body becomes impossibly tall and sad in order to convey his “uneasy Olympian attitudes.” Carson, who prosecuted Wilde, is a long curve like a tense whip, whereas Balfour is a question mark. Beerbohm thickened Kipling’s neck and enlarged his jaw to stress the brutality he saw in him. Pinero’s eyebrows had to be “like the skins of some small mammal, just not large enough to be used as mats.” One difficulty, he noted, is that over the years a subject may change—the arrogant become humble, the generous mean, the sloppy scrupulous (he noted in How They Undo Me). Yeats had once seemed like a “mood in a vacuum,” but the youthful aspect changed:

I found it less easy to draw caricatures of him. He seemed to have become subtly less like himself.

As Mr. Felstiner adds, a shade unnecessarily,

The truth is that he [Yeats] had become more like himself…. An evolving discipline made his themes and his style more toughminded, idiomatic, accountable….

Mr. Felstiner has noticed that in Max’s caricatures the eyes of the politicians are generally closed—they might be ridiculous statues—but the eyes of the writers and artists are open. The eyes of James are wide open—sometimes in dread. Beerbohm wrote a sonnet to him: “Your fine eyes, blurred like arc lamps in a mist.” Beerbohm’s admiration for James and his closeness to his belief in the primacy of art are responsible for the excellence of his well-known parody in The Christmas Garland. It required an art equal—for a moment only—to James’s own to get so keenly under the skin; and, like all good things, it was not achieved without enormous trouble. Indeed, Max added to the famous Christmas story one more turn of the screw.

He constantly revisited his subjects. His parodies are indeed criticisms and the silent skill with which nonsense is mellifluously introduced, without seeming to be there, is astonishing. James’s manner has often been mimicked, but never with Beerbohm’s gift for extending his subject by means of the logic of comedy. I do not share Mr. Felstiner’s admiration for the Kipling parody: Max was blind to Kipling’s imagination though he was daring in suggesting there was something feminine in Kipling’s tough masculine worship of obedience. Max here disclosed a violence on his own part. Kipling was as good an actor as he; he had been brought up by a pre-Raphaelite father and had as much regard for form and style as Beerbohm had. But, of course, like greater artists, the parodist celebrates his own blindnesses as well as his power to see.

He could even show open schoolboy coarseness in a way that is surprising in one of his circumlocutory habit. There are a few lines on Shaw, an old love-hate, in J. G. Riewald’s edition of rhymes and parodies, Max in Verse:

I strove with all, for all were worth my strife Nature I loathed, and next to Nature, Art

I chilled both feet on the thin ice of Life It broke and I emit a final fart.

This book has some of Beerbohm’s best things: the parody of Hardy’s Dynasts, the pseudo-Shakespeare of Savanarola Brown—only Max could have seen what could be done with splitting up iambic pentameters in banal dialogue. The Shropshire Lad is told abruptly to go and drown himself; and for those puzzled about the origins and pronunciations of English place names like Circencester, there is a gently malicious ballad. Thirty-four of these poems have not been published before, partly because Max was very tactful, at the proper time, about hurting people’s feelings—he repressed the keyhole James until after James’s death—and partly because he knew when he had prolonged his juvenile phase too long.

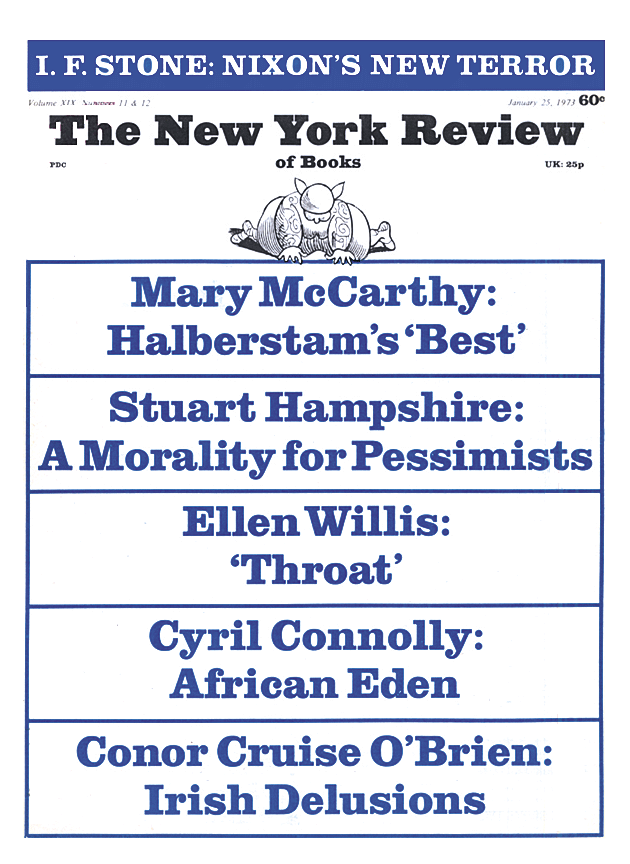

This Issue

January 25, 1973