In April, 1969, Arthur Burns, then a counselor to President Nixon, now the chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, launched a strong attack within the White House on the “family security system” about to be adopted by Mr. Nixon. Burns caused to be prepared, among other documents, “A Short History of a ‘Family Security System’ ” taken from Karl Polanyi’s account of an eighteenth-century British experiment in poor relief commonly called “Speenhamland.” Polanyi’s account claimed that the income assistance provided to wage workers by Speenhamland had shattered the self-respect, productivity, and independence of the recipients. The Nixon plan, Burns suggested, would have the same result in twentieth-century America.

Two years later, with the Nixon proposal renamed a “Family Assistance Plan” and deeply involved in legislative battles, Frances Fox Piven and Richard A. Cloward again compared it to Speenhamland, in an article in transaction (May, 1971). Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who as director of Mr. Nixon’s Urban Affairs Council in 1969 had been a principal architect of FAP, now writes that “in this reaction” Piven and Cloward “exemplified the view Nathan Glazer has termed the radical perspective in social policy.” That is, they exemplified what Glazer had said was the radical belief “that there can be no particular solutions to particular problems but only a general solution, which is a transformation in the nature of society itself.”

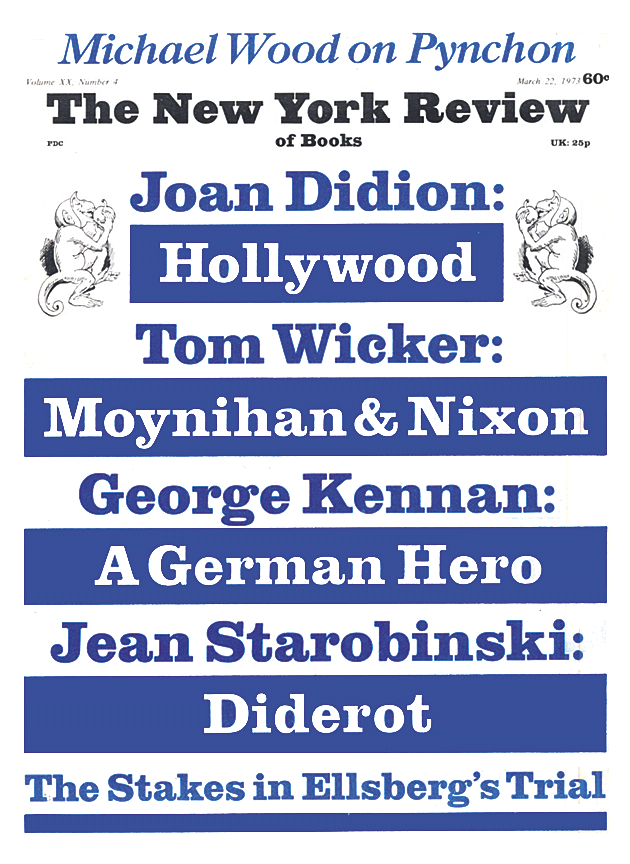

But curiously enough, Moynihan ascribes none of Glazer’s so-called “radical perspective” to Arthur Burns, even for the same offense. Rather, after refuting Burns’s view, he comments in an effusive footnote “on this remarkable man…an economist of formidable power.” This is a matter of small moment, as compared to the heft of Moynihan’s long and extraordinary book on the rise and fall of FAP, but it points straight to one of its problems—perhaps its major problem.

The Politics of a Guaranteed Income, it should be said at the outset, is a first-class piece of work, maybe the best we have—anyway the best written in English rather than social scientese—on the interplay of government and politics in America, on the complexities hidden in John Kennedy’s frequent remark that “to govern is to choose,” on the difficulties of defining social need, suiting political action to it, and persuading a bewildering constellation of interests and institutions to take and sustain that action. At that high level, Moynihan succeeds brilliantly. Moreover, as he might write in his pontifical yet readable style, Moynihan has the standing to offer us such a work; having served in the cabinet or subcabinet of the Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon administrations, with an imposing academic background in the social sciences, and with one of the quickest intelligences in public or university life today, Moynihan writes with rare authority, with perception tempered by experience, and without much illusion.

His book is full of sage counsel and striking analyses, both of what ails and what distinguishes us. “If there is a pattern among [Americans],” he writes, for example, “it is that of denying the existence of a problem as long as possible, and thereafter quickly ascribing it to some generalized failing of society at large.” Of Congress, which so few academics seem able to comprehend, he observes cogently: “Decision-making is not at the core of its being: representation is.” This was a lesson hard learned, perhaps, from the fate of FAP. And here is Moynihan, often a liberal target in recent years, on the predicament of liberalism after the Tonkin Gulf incident:

The Vietnam war—in no small way, liberalism’s war—was seen to have been profoundly misconceived. In the penumbra of this intense moral revulsion, questions arose about the whole of liberal doctrine in its applied forms. Had they opted for a meliorative view of events that was not sufficiently demanding of either intellectual or political effort? Had they allowed a genuine passion for racial justice to degenerate into something ominously close to acquiescence in self-defeating behavior that perpetuated racial inequality? Had they held to a model of social processes that vastly exaggerated the potential of mild governmental interventions?

Breathes there a liberal with soul so dead that he has not forced himself to consider, if not answer, these questions?

Unfortunately, there is another and prominent level at which The Politics of a Guaranteed Income works only superficially, if with a certain gloss of plausibility: as an apologia for Richard Nixon and as an indictment of liberals, Democrats, “radicals” like Piven and Cloward, middle-class social workers, and the press, all of whom in Móynihan’s view must share the responsibility for the loss of what he believes—probably rightly—would have been the greatest social advance since the Social Security Act, or perhaps in this century.

Intruding this material on the book, to borrow a frequent Moynihanism, “had consequences.” Not only did it make the author seem occasionally condescending, petulant, and even mean-spirited (as in the attack on Piven and Cloward), as if he were part of an interdepartmental doctrinal feud among the associate professors at an especially rarified university (“It was perhaps to be expected that persons associated with public broadcasting would assume that a guaranteed income was a proposal that belonged to Democrats…”; “There was no possibility of getting the press to see otherwise…”; “But this required more subtlety than is typically found among political strategists…”). Worse, Moynihan appears to have concentrated so much on paying off scores and pursuing his thesis that he does not draw the more useful conclusions that by his own account seem to me unavoidable.

Advertisement

Why was it necessary, for example, to contend that Mr. Nixon “never really publicly declared his support for the war,” which shaves a fine point to infinity, and then to declare righteously that all that mattered “in terms of the national press and the liberal audience was that he did not denounce it and dissociate himself from it”? That was not at all true of most of the “national press,” which was and is pro-Nixon; as for the “liberal audience,” was it really to turn from opposition to Mr. Johnson’s war to support for Mr. Nixon’s Vietnamization, which required the invasion of two countries and the bombing of three in order to evacuate one (not to mention four more years and unnumbered Vietnamese and American deaths)?

It is ungracious and untrue, moreover, to write that “a decade of Northern lawyers poking federal injunctions into the hands of Southern politicians and hastening back to Georgetown with tales of redneck vulgarity had produced—what?” Federal civil rights efforts by 1969 had produced a substantial effect in the South, and most of those who sometimes risked their lives to bring about that effect were not Georgetown “elites.” As for redneck vulgarity, Moynihan himself remarks on the “intellectual backwardness” he apparently supposes to be the mark of the South.

This is introductory to the claim that it was Richard Nixon who finally desegregated Southern schools and “implanted” the idea in the South that compliance with court orders was the right thing to do. The schools were desegregated heavily in Mr. Nixon’s years in office, but mostly as the result of court decisions, some of which his Justice Department actively opposed; and if Mr. Nixon implanted any such idea, it was in soil first poisoned by his 1968 campaign rhetoric against forced desegregation, and in favor of “freedom of choice.”

As in his differing treatment of Arthur Burns and Piven and Cloward, Moynihan often seems to excuse in conservatives and Republicans what he condemns in Democrats and liberals. In a long footnote on the failure of certain Great Society programs, he laments the fact that “because [Mr. Nixon] had always assumed that such programs fail, it was too much to hope that an assertion by him that they had failed would be accepted as reflecting a fair-minded reading of the evidence.” But that is only the other side of a coin that Moynihan often cites—that no liberal president, only a conservative like Mr. Nixon, could have proposed anything so radical as a guaranteed income. Such ironies cut both ways.

Moynihan would have it that liberals despised Mr. Nixon too much to support even a liberal social initiative by his Administration; that liberals, Democrats, and professional social workers were so committed to New Deal and Great Society “services” programs that they could neither concede their considerable failure nor recognize Mr. Nixon’s bold new income approach; and that all these became easy dupes of conservative forces and black militants who had their own reasons for wanting to defeat a guaranteed income proposal.

Obviously, there is some truth in all of that, and the polished authority—even the occasional absolution for his misguided adversaries—that Moynihan brings to the account, together with the general disrepute into which liberalism has fallen, undoubtedly will give this thesis much currency. That only serves to obscure, I believe, the greater truth of The Politics of a Guaranteed Income—that guaranteed income is an idea whose time has not yet come in America. If anything, the defeat of FAP in two consecutive Congresses, as well as George McGovern’s bungled $1,000 demogrant scheme, set the idea back. Early last summer, as old guaranteed income proponents, Moynihan and I were congratulating ourselves that at last both candidates in a Presidential election apparently would be touting guaranteed income; but by the time McGovern floundered down to Wall Street in August to bury, not to praise, his demogrants, that notion had gone glimmering. If Mr. Nixon mentioned FAP in what passed for his campaign, it escaped my notice.

No one can prove or disprove a negative, of course, and it may be that if certain things had turned out differently—if liberals had been of larger spirit and if the welfare mothers Russell Long called “black brood mares” had been of greater restraint—FAP would have passed and transformed society. Moynihan’s book leaves me in considerable doubt of that. He makes much—as a means of emphasizing how close success was—of a study in 1969 by the social scientists Cavala and Wildavsky that concluded, “Income by right is not politically feasible in the near future. The President will not support it and Congress would not pass it if he did. The populace is hugely opposed.” In fact, Mr. Nixon soon proposed FAP, the House twice passed it, the Senate twice let it die, and the public never seemed much exercised at its fate.

Advertisement

Were Cavala and Wildavsky so wrong? One of Moynihan’s most extraordinary insights is that the only success FAP actually had was through “a decision-making process in the White House in which sufficient power was concentrated in one man that a decision was possible” and in “the House of Representatives where substantially the same condition obtained.” It obtained there because Chairman Wilbur D. Mills of the Ways and Means Committee, whom Moynihan much admires, “was equally capable of assessing…and responding in a purposeful manner…” and decided to support the Nixon proposal. “Mills’s decision,” writes Moynihan, who displays a sensitive if admiring understanding of the House and its most powerful committee, “was accompanied by a general decision of the House leadership to support FAP.” This assured the rule forbidding amendments under which the House voted and “this in turn ensured the passage of FAP.” It does not much oversimplify to state that once Richard Nixon and Wilbur Mills “assessed and responded,” FAP was assured of going precisely as far as it did; past that point, one-man decision making became impossible and FAP failed politically.

Moynihan is at pains, for another thing, to insist on Mr. Nixon’s commitment to FAP, despite the Democrats’ persistent suspicion that the President was not much in favor of his own bill; but the record as laid down in The Politics of a Guaranteed Income suggests that, at the least, Mr. Nixon’s support resulted from a calculated policy decision rather than from inclination or instinct. There is nothing reprehensible or unusual in that, but the analytical nature of the President’s commitment appears here to have given his opponents more ground for their suspicions than Moynihan wants to admit. And while his book was written too soon to deal with the Nixon of 1973, it is fair to point out that so far from using the 1972 landslide to reinforce his earlier demand for FAP, Mr. Nixon has let the program disappear entirely from his second Administration agenda.

In 1968, he had taken office, according to Moynihan, believing that welfare was “a terrible experience…awful…” and thus more willing than other presidents to do something “radical” about it. But he seemed to have no idea what to do; he had not campaigned much on the subject, or made any “radical” proposals; he and those around him only knew, Moynihan tells us, that “Nixon needed something to distinguish his Administration from that of his predecessors.” So the clever Moynihan, a much more experienced staff man than most of his colleagues in 1969, “proposed a theme which quickly caught on in the President’s circle, and which later became official: his was a reform Administration.”

If a reform Administration, even one by choice rather than by instinct, was to do something about scandalously rising welfare dependency—Moynihan gives us a meticulous history of this phenomenon and as good an analysis as we are likely to get of why it took place—the most convincing case could be made for an “income strategy.” If the poor lacked money, give them money; it was “direct, efficient, immediate,” it would put some responsibility for results on the poor themselves, it was color-blind (important to an Administration with its eye on the hardhat and Wallace voters), it would reach the working as well as the dependent poor. And the New Dealish “services strategy” of the Johnson years had proved not only ineffective but divisive. Finally, an “income strategy” would be a smash-hit departure from previous policies and establish the Nixon Administration as an innovative reform government.

There was a negative income tax proposal in the files, rejected by the Johnson Administration (Moynihan is rightly caustic about the extent to which too many years of office and too little intellectual diversity had caused the Democrats to become by 1968 “the party of timidity”). The new President adopted it in a Republican modification and stuck with it, Moynihan writes, because of “three propositions.” The first was that the old welfare system was destroying the poor, “especially the black poor.” The second was that income assistance held out the hope of ending poverty in the South, that perennial drag on the rest of the country. And “finally it was necessary to prove that government could work…America needed some successes.”

Thus, as Moynihan puts it, “the legislation was almost altogether the result of professional analysis of what was wrong and what had to be done. There was as near as can be to no public support for a guaranteed income.” And, he makes clear, precious little within the Nixon Administration—“Apart from those personally and directly involved, the Nixon Cabinet never really fought for the President’s most important domestic proposal. It wasn’t theirs. They didn’t quite understand it.” As time wore on, “not unexpectedly, the Republican party organization showed no great enthusiasm, nor did the minority leadership in Congress….” FAP, we get the impression, was like a doctor’s unwelcome recommendation that his patients lose weight or quit smoking; it may have made sense, and the best informed accepted it, but nobody was really enthusiastic.

Some were downright opposed. “Within the White House and the Administration, there developed a group that wished to see FAP defeated,” Moynihan concedes, although he labels these anonymous defectors “lower-level political cadres.” Nevertheless, when “this somewhat nebulous White House group” intimated to senators “that the President’s support for the legislation was wanting,” were partisan Democrats supposed to brush aside such testimony? They had all too much evidence, anyway, to support what the low-level cadres were whispering in their ears.

For one thing, Mr. Nixon’s Cambodian incursion came along to distract his attention from his domestic program just when FAP most needed his interest and support, and to lower his public and congressional standing precipitately. Moynihan concedes that the President’s attention “was usually elsewhere” and on one devastating page he gives us what may be the real measure of Mr. Nixon’s concern. On August 28, 1970, he writes, when FAP was all but lost among the Piltdown men of the Senate Finance Committee (where it ultimately died), Mr. Nixon made “from San Clemente” (!) an important concession in an attempt to win support. “Finch, Veneman and I presented the statement,” says Moynihan, adding with apparently unconscious irony, “evoking all the sense of urgency we could.” He is not without the grace to add, however, that “four months earlier” even this long-distance, proxy performance “might have been formative.”

Now at the very least, if a bill so nearly revolutionary as Moynihan, without much exaggeration, pictures FAP to have been is ever to pass the American Congress, a more militant, personal, and aggressive performance than that will be required of the President who presents it—particularly if that President is Richard Nixon, the blood enemy of Democrats and liberals for a quarter-century. Why, it is reasonable to inquire, should anyone, let alone as sophisticated a political man as Pat Moynihan, consider it the duty of an opposition accustomed to Nixon as anticommunist, anti-Democrat, and a cutthroat campaigner to come to his political rescue on a difficult issue about which he himself showed so little zeal?

There is nothing, moreover, in Moynihan’s voluminous record to suggest that the President and his aides ever thought much about winning Democratic or liberal votes; they seem to have assumed that they would or ought to get these because they were proposing an innovative and un-Republican plan to improve the lot of the poor, about whom Democrats and liberals had spouted so much oratory. There may have been an unconscious tribute to the left here, if it was assumed that Democrats and liberals would rise above politics and personality to their duty; but it was sadly misplaced, if so, because it is the conservatives who most often hew to the line of principle and ideology. In this case, it was conservatives who seemed most likely to be outraged by a guaranteed-income proposal, and it was to conservatives that the Administration’s political guile was directed. To a critic, the adept speech-writer William Safire explained: “You miss Richard Nixon’s main point, which is to make a radical proposal seem conservative.”

That was the Administration’s basic political approach, an exercise in what Moynihan calls “symbolic politics.” Mr. Nixon understood, he writes, “that the American public was willing to accept liberal programs when cast in nonliberal terms,” but that something so far-reaching as FAP also required nonliberal sponsorship; even so, it could not be called “guaranteed income.” If, as Mr. Nixon believed, “the American people were willing to support the dependent poor altogether, and to give a hand to the working poor, it was hardly his responsibility to endanger this likelihood by insisting that doing so would involve embracing the principle of a guaranteed income, which he had every reason to think the public would not be willing to do.” Moynihan believes it “the mark of the mature political mind” to understand and accept the “symbolic politics” thus required; that might ordinarily be so, but remember this was 1969 and there was much to suggest that many Americans were disillusioned with such indirection and dissembling—calling an escalation of war “no change in policy,” for instance.

At any rate, from the start of the FAP debate, “there arose a tension between symbol and substance that was never to be allayed. The proposal was a guaranteed income, and there was no work requirement” (Moynihan’s italics). Yet, said Mr. Nixon in his television address announcing the program, “this…is not a ‘guaranteed income.’ ” To the Ways and Means Committee, George Shultz began his testimony, “This is not a proposal for a guaranteed minimum income. Work is a major feature of this program.” When the matter reached the Senate Finance Committee, where there was no Wilbur Mills to order affairs, the price had to be paid with more than symbols and rhetoric. Conservatives like the formidable John Williams of Delaware ferreted out numerous work disincentives in FAP and “the Administration, because of its own characterization of the program, was forced to try to eliminate them. It could never do so completely, and so could never satisfy the conservatives.” But every time it tried, it further dissatisfied the liberals because “with each adjustment…some family somewhere was deprived of a right-in-being” (Moynihan’s emphasis again).

Throughout, “the problem always was assumed to be that of keeping conservative support. As finally assembled the proposal contained major components designed to respond to conservative concerns and to merit their backing…. The right, in the person of [Governor Ronald] Reagan, had come within breathing distance of the Republican nomination in 1968” and until the election of 1970 the White House believed he might actually win in 1972—not least because of conservative resentment of FAP.

Even so, the symbolic conservatism in which Mr. Nixon bathed FAP never converted Reagan, the US Chamber of Commerce, the Southern Democrats, or even the Republican minority of the Finance Committee. William F. Buckley, Kevin Phillips, James Jackson Kilpatrick, and Human Rights rumbled angrily on the right wing of the press. Milton Friedman, the conservative father of the negative income tax, disowned his child when he saw the way Mr. Nixon had brought it up. Meanwhile, Mr. Nixon was invading Cambodia, and it appears from Moynihan’s book that liberals and congressional Democrats were left to understand for themselves that FAP was really their kind of thing (although the hue and cry over McGovern’s demogrants later showed that most liberals are not much keener for guaranteed income than conservatives) and that Mr. Nixon really cared about the plan. They drew no such conclusions, which ought not to surprise or even dismay a man with the political sensitivity to write that “one of the arts of government is to avoid the humiliation of the interests that lose out in the clash of policy.” Or, he might have added, in the clash of symbols.

So here was a conservative President, committed by analysis rather than intuition or pressure to what he regarded as a liberal bill in conservative drag, trying to placate an implacable right while neglecting an unsettled and unhappy left. Here was legislation that represented a sharp departure from conservative ideas about work and from liberal ideas about social services. Plainly, FAP would have been in trouble—once out from under Mr. Mills’s sheltering wings—even had Mr. Nixon been able to give it his undivided attention.

All this was compounded—I am now drawing my own conclusion from Moynihan’s testimony—by the circumstances that FAP was not a good bill. The guaranteed income proposal might well have been the important advance Moynihan (and I) believe it would have been, but the legislation that embodied FAP was something else. No wonder, in retrospect, that so many who were kindly disposed to FAP in 1969 and 1970 found themselves eventually calling for its enactment mostly because it represented a good principle. “The problems can be ironed out later,” it used typically to be said.

That would have been true only if there had been an overwhelming public and congressional consensus for the principle, and there never was. As a result, given its defects, FAP was, as the football coaches say, “nickle and dimed to death.” It could not even be argued, as Moynihan had argued years before for a children’s allowance, that it would be simple and would require no huge bureaucracy to administer. FAP would have signed on 25,000 new federal employees and cost $250 million a year to operate. Moynihan concedes that “the proposal was hard to understand” and that Arthur Burns had warned from the outset that that would make it easy to misrepresent (which it frequently was, whether by design or inadvertence).

But perhaps the basic problem with FAP as legislation (as distinct from the guaranteed income principle) was that the Administration as part of its hold-the-right strategy oversold the bill as “welfare reform” or “workfare.” Not only, as Moynihan points out, did “the rhetoric of workfare fundamentally challenge the ideology of welfare,” which aroused liberals, welfare militants, and social work professionals, but there were, in fact,

two symbolic issues at stake. On the one hand, welfare reform: on the other, the guaranteed income. In substance the measure involved both: it was reform, it was an income guarantee, but much more assuredly the latter than the former. The state of knowledge, if anything, exaggerated the distinction. That FAP would establish a guaranteed income was demonstrable: a fact of definition. That it would reform welfare could at best be hoped for, and hopes were minimal.

Thus such divergent Democrats as Martha Griffiths of Michigan and Long of Louisiana were more concerned with the supposed welfare reform than with the guaranteed income. What, Mrs. Griffiths wanted to know, would FAP do about illegitimacy, about desertion, about dependency; and would it not apply the bulk of its funds outside “the cities that need the remedy”? Long, on the other hand, wanted to know how FAP would tighten up welfare against abuses and get the cheaters off the rolls; and when he started inquiring about that, FAP had to be tailored more nearly to his views—which only meant that Mrs. Griffiths’s different concerns would become more pronounced.

The Administration, to its credit, had taken a longer view; frankly not knowing—as no one does—what to do about dependency, it had chosen income supplementation for the working poor as a long-range effort to keep them from sinking into the welfare class. But this overlooked, first, the political fact that such public concern as there was was with welfare, particularly its abuses; and second, the contrary political fact that welfare, rightly or wrongly, had a powerful constituency of its own that, like Mrs. Griffiths, was bound to see FAP shifting interests and benefits to the working poor and away from the welfare dependents concentrated in the cities.

“The short-term effect of family assistance would be to improve the conditions of the nondependent poor relative to the dependent,” Moynihan acknowledges. “The Administration knew this, but judged that the interests of welfare recipients in the poor states and of the working poor, again especially in the South, had priority.”

That is another analytical judgment, another correct decision, which turned out to have no political vitality. Since when, Moynihan of all political realists will not mind being asked, did interest groups look to the long run rather than the short range? And why were welfare mothers expected to take the long view when the Administration was doing all it could to convince conservatives (of whom no great foresight was asked) that FAP was “workfare,” and was trying to conceal from all sides that it was primarily a guaranteed income for the working poor?

FAP would, in fact, have reduced cash benefits to some welfare families; after the Senate amendments forced by Williams, Long, and others, it also contained some regressive provisions that welfare recipients and professionals opposed—for instance, elimination of a program that permitted benefits to the children of an unemployed father, even if he was resident in the household. Those who were to be put to work would be required to work for $1.20 an hour, less than minimum wage. None of this justifies outsized demands such as the National Welfare Rights Organization’s proposed $5,500 minimum income guarantee for a family of four; but it goes a long way to explain the opposition of NWRO to FAP. Interest-group politics, which Moynihan otherwise extols and brilliantly explains, only rarely rises above interest.

If opposition developed to the welfare reform provisions of FAP, no real support ever materialized for its guaranteed income scheme—save the important conversion of Wilbur Mills. In fact, even as guaranteed income, there are suggestions here that FAP was seriously deficient. George Shultz had to concede to the Ways and Means Committee that in forty states where there would be state supplementation of federal payments, the states as well as the federal government would reduce their payments as a family’s earnings rose. These reductions meant there would, in effect, be a “marginal tax rate” of 67 percent on the income earned by people benefiting from FAP. (The marginal tax rate is the percentage of additional income paid in increased taxes.) Milton Friedman then pointed out that Social Security taxes at 4.8 percent of earnings would bring the real marginal tax under FAP to 71.5 percent—not much of a work incentive.

In all of these circumstances, trying to fix blame for the failure of FAP is a little like trying to decide who elected John F. Kennedy in the narrow victory of 1960. Was it the Southern states Lyndon Johnson “held” for the ticket, or the Liberal line in New York, or the huge majority in Philadelphia that carried Pennsylvania? It could have been any of them but in fact it was all, and that appears to have been true of those who opposed or failed to support FAP; and if Moynihan seems overly censorious of liberals and welfare militants, he is candid enough about many of the deficiencies of the Administration and of the legislation itself.

Perhaps the real question is not dealt with in The Politics of a Guaranteed Income because as a “participant historian” Moynihan is primarily telling us what happened. But what would have happened, it might be well to ask, if the President had opted differently in 1969—not for a substantially different program but for a different way of presenting it? Moynihan believes that Mr. Nixon’s adoption of FAP and the near-success in Congress developed from the fact that, at some point, incremental changes in program and policy are plainly not enough to deal with developing social needs; and that the FAP experience showed that “fundamental reform of existing social policies” is a live possibility in the American system.

Obviously, in a presidential system, the odds are overwhelming that such a reform would be on White House initiative, and the question is whether such an initiative can ever succeed without a persisting and straightforward—at least as bold as the decision itself—presidential exposition of the issues involved. When it is considered how long, for example, it took to achieve Medicare (scarcely a “fundamental reform,” at that) and how hard both Presidents Kennedy and Johnson had to work to explain the Keynesian economics of the 1964 tax bill (a heretical measure in those days), it seems fair to question not just Mr. Nixon’s commitment but his tactics of “workfare” rhetoric.

“By no standard,” says Moynihan, splitting hairs, could the Nixon speeches of the 1970 congressional campaign be considered hostile to welfare mothers; but what were embattled Democrats and liberals to think when the President declared in Long-view, Texas, on October 28: “I will put it very bluntly. If a man is able to work, if a man is trained for a job, and then he refuses to work, that man should not be paid to loaf by a hardworking taxpayer in the United States of America. That is the program we stand for.”

This statement was an act of considerable political loyalty, because it was in behalf of Representative George Bush, who was being attacked for having supported FAP. But Bush lost his Senate race anyway, and the “symbolic politics” of that speech and others like it went far beyond its setting. I happened to hear the Long-view speech and the roaring Texas response, and “by no standard” can either have been considered an educational effort on behalf of the principle of guaranteed income in America.

My own supposition, confirmed by The Politics of a Guaranteed Income, is that FAP, as Cavala and Wildavsky had predicted, had little chance in the 90th and 91st Congresses, no matter what Mr. Nixon said or did. But suppose that this President—a dogged man if ever there was one—had been steadily preaching the doctrine of guaranteed income since 1969, and even today was still relentlessly pounding away at the theme, with the full might of the “bully pulpit” and from his own conservative position? By now there might be a public climate of acceptance at least of that principle so nearly lost in the wreckage of FAP and demogrants. Or maybe not; as Daniel P. Moynihan knew all along, “to redistribute income is to redistribute political power,” and the American system does not seem a particularly good instrument for either purpose.

This Issue

March 22, 1973