John Dos Passos wrote this letter to his friend Rumsey Marvin while serving as an ambulance driver in France during World War I. It will appear in The Fourteenth Chronicle: Letters and Diaries of John Dos Passos, edited by Townsend Ludington, to be published by Gambit in the autumn.

August 27 [1917]

By candlelight in a dugout—Outside it is raining & German shells falling sound like infinities of heavy chain dropped all at once

Dear Rummy—

I’ve wanted time after time to write you & have produced many unwritten letters—you know the kind—Also two delightful letters from you have spurred me on—

But I’ve had so much to say & so much of it will be so hostile to your ears, you old militarist, that I haven’t known where to begin.

Let’s see When did I last write? It seems that it was in Sandricourt, when I was enduring the sorrows of training camp—After that we formed our section, S.S. U60 in Paris & jaunted by easy & unwarlike stages to a town on the Sacred Way, a little above Bar le Duc of blessed reputation—Ah but I’ll continue in the morning—Imagine me stretched out on a stretcher on the floor of the dugout listening to the German shells whistling overhead & wondering if a chance one’ll hit our roof—

Aug 29

I am sitting in the charming weedgrown garden of a little pink stucco house whose shell only remains & if fortune favors I shall finish this letter. It is a delightful day of little sparkling showers out of thistledown clouds that the autumn nipped wind speeds at a great rate across the sky. I’ve not been on duty today—so I’ve been engaged in washing off to the best of my ability the grime and fleas of two nights in a dugout. Nos amis les boches have been keeping us excessively busy too, dropping large calibre shells into this town; as if the poor little place were not smashed up enough as it was.

We stayed for two weeks with our feet in the mud at Erize la Petite—a puny & ungracious hole—There the only interest was watching the troops, loaded on huge trucks—camions—go by towards the front where an attack was prophesied.

For some reason nothing I’ve seen since has affected me nearly as much as the camion loads of dusty men grinding through the white dust clouds of the road to the front. In the dusk always, in convoys of twenty or more escorted by autos full of officers, they would rumble through the one street of the ruined village.

The first night we were sitting in a tiny garden—the sort of miniature garden that a stroke of a sorcerer’s wand would transmute into a Versailles without changing any of its main features—talking to the schoolmaster and his wife; who were feeding us white wine & apologizing for the fact that they had no cake. The garden was just beside the road, and through the railing we began to see them pass. For some reason we were all so excited we could hardly speak—Imagine the tumbrils in the Great Revolution—The men were drunk & desperate, shouting, screaming jokes, spilling wine over each other—or else asleep with ghoulish dust-powdered faces. The old schoolmaster kept saying in his precise voice—“Ah, ce n’était pas comme ça en 1916…Il y avait du discipline, Il y avait du discipline.”

And his wife—a charming redfaced old lady with a kitten under her arm kept crying out

“Mais que voulez vous? Les pauvres petits, Ils savent qu’ils vont à la mort”—I shall never forget that “Ils savent qu’ils vont à la mort”—You see later, after the “victory,” we brought them back in our ambulances, or else saw them piled on little two wheeled carts, tangles of bodies with grey crooked fingers and dirty protruding feet, to be trundled to the cemeteries, where they are always busy making their orderly little grey wooden crosses—

It’s curious. Do you remember Jane Addams’ statement that everyone in America jeered at, about the French soldiers—all the soldiers in fact, being doped with rum? Its absolutely true—Of course anyone with imagination could have guessed anyway—(there went a shell—near our cantonment too) that people couldn’t stand the frightful strain of deathly—literally so—dullness without some stimulant—In fact strong tobacco, very strong red wine, known to the poilus as Pinard, and a composition of rum & ether—in argot, agnol, are combined with the charming camaraderie you find everywhere—the only things that make life endurable at the front—

Having our headquarters in the much bombarded remnants of a village, we do our business in a fantastic wood, once part of the forests of Argonne—now a “ghoul haunted woodland”; smelling of poison gas, tangled with broken telephone wires, with ripped pieces of camouflage—(the green cheesecloth that everything is swathed in to hide it from aeroplanes), filled in every hollow with guns that crouch and spit like the poisonous toads of the fairytales. In the early dawn after a night’s bombardment on both sides it is the weirdest thing imaginable to drive through the woodland roads, with the guns of the batteries tomtomming about you & the whistle of departing shell & the occasional rattling snort of an arrivée. A great labor it is to get through too, through the smashed artillery trains past piles of splintered camions and commissariat waggons. The wood before and since the attack—the victory of August 21st—look it up & you’ll know where I was—has been one vast battery—a constant succession of ranks of guns hidden in foliage, and dugouts, from which people crawl like gnomes when the firing ceases and to which you scoot when you hear a shell that sounds as if it had your calling card on it—

Advertisement

The thing is that we, on our first service, landed in the hottest sector ambulance ever ambled in. My first night out I was five hours under gas—of course with a mask, or I shouldn’t be here to tell the tale—

But the whole performance is such a ridiculous farce. Everyone wants to go home; to get away at any cost from the hell of the front. The French soldiers I talk to all realize the utter uselessness of it all; they know that it is only the greed and stubbornness and sheer stupidity of the allied governments &, if you will, of the German government, that keeps it going at all—Oh but why talk?—its so useless—There is one thing one learns in France today, the resignation of despair—

Still, I’m much happier here really in it than I’ve been for an age. People don’t hate much at the front; there’s no one to hate, except the poor devils across the way, whom they know to be as miserable as themselves. They don’t talk hypocritical bosh about the beauty & manliness of war: They feel in their souls that if they weren’t cowards they would have ended the thing long ago—by going home, where they want to be. And lastly and best, they don’t jabber about atrocities—of course, everyone commits them—though about one story in a million that reaches our blessed Benighted States is true.

But I really must shut up. More later—

Love—

Jack

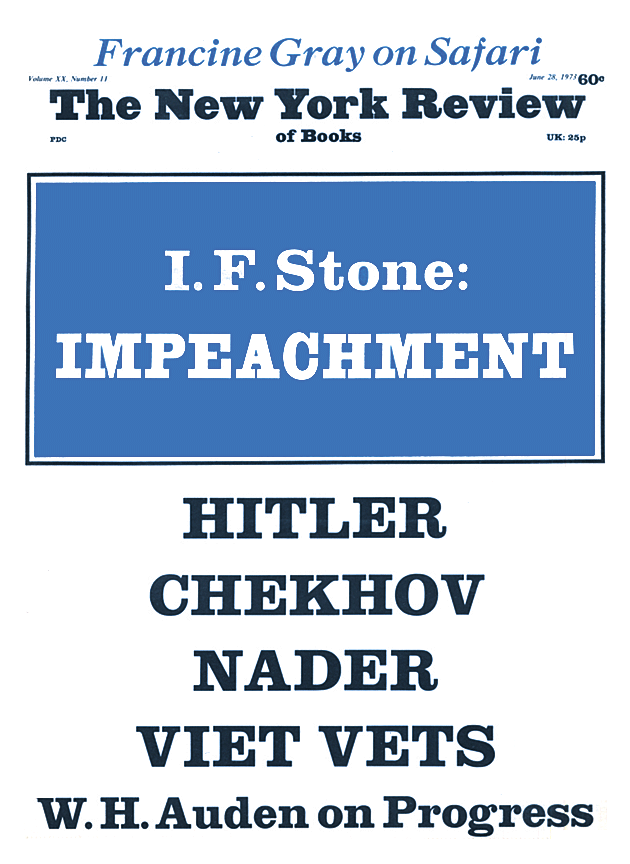

This Issue

June 28, 1973