In response to:

Owing Your Soul to the Company Store from the November 29, 1973 issue

To the Editors:

In reading Ralph Nader and Mark Green’s November 29 article about the abuse of corporate power, I was struck by the flat assertion that San Francisco’s high rise construction is, “…costing eleven dollars in services for every ten dollars the high rises contribute in taxes.” That is not true. Some consider the new high rise buildings undesirable because they do change the pre-existing architectural look of the city. The new high rises also tend to use more energy than older structures. But to say they don’t pay their own way in the narrow fiscal sense of public service costs versus tax contributions is so erroneous as to cast doubt on the validity of the other charges leveled in the article.

San Francisco’s civic books are not set up for easy spatial cost accounting, so it is hard to come up with an exact public profit and loss statement for the tall buildings, but office buildings, commercial stores, and banks make up over 21 percent of San Francisco’s assessment base. Highrise structures are fully assessed and pay the full property tax rate. That tax brings in about 70 percent of all locally generated revenues. About 16 percent of the city’s expenditures go to general administrative functions that would still be required even if no high rise structures were ever built. Of the remaining expenditures, 21 percent goes to public welfare, 21 percent to public safely, 31 percent to schools, 14.5 percent to streets, sanitation, corrections, and miscellaneous, while 12 percent goes to health and hospitals. Thus all but a small percent of the city’s dollars are spent on serving people whose needs would not shrink with the removal of the high rise structures that provide space for several hundred thousand workers in San Francisco. Many of these workers live in surrounding communities so that their children do not get their schooling from the City and County of San Francisco.

Most of the people-serving costs San Francisco and our other major metropolitan centers pay would still be required here if high rise buildings were to disappear. While their desirability should be judged on more than fiscal grounds, their marginal revenue contributions exceed the marginal costs they impose upon the city.

Urban problems will never be solved, or urban strengths built upon, if we fabricate charges that suggest our problems stem from tall buildings or any other simple physical manifestation of underlying economics and social forces. Nor can we really identify and deal with the antisocial abuses of corporate power if we shot gun big business with real and fallacious charges.

Claude Gruen

San Francisco, California

Mark Green and Ralph Nader replies:

It is good that Union Camp is finally beginning to clean itself up, but that is hardly an occasion for self-congratulation. Union Camp—compelled by federal and state antipollution laws and authorities, chastised for its environmental insensitivities in the 1971 Water Lords by James Fallows, subsidized helpfully by municipal bond—has come to see the light only when it felt the heat. A Georgia water official told us on February 7, 1974, “Of course they didn’t clean up voluntarily. We had to threaten to go to court with them, and they saw the handwriting on the wall.” Also, Union Camp has perhaps spent more than other mills on pollution controls at its Savannah plant because that plant was so much more polluting than comparable paper mills.

As for Claude Gruen’s assertions concerning our comment that San Francisco’s high rise construction has cost more in services than it has generated in tax revenues—we refer him and any interested readers to a report published by The San Francisco Bay Guardian, which clearly documents our statement. (The Ultimate Highrise—San Francisco’s Mad Rush to the Sky, obtainable from The San Francisco Bay Guardian 1070 Bryant St., San Francisco, Cal. 94103.)

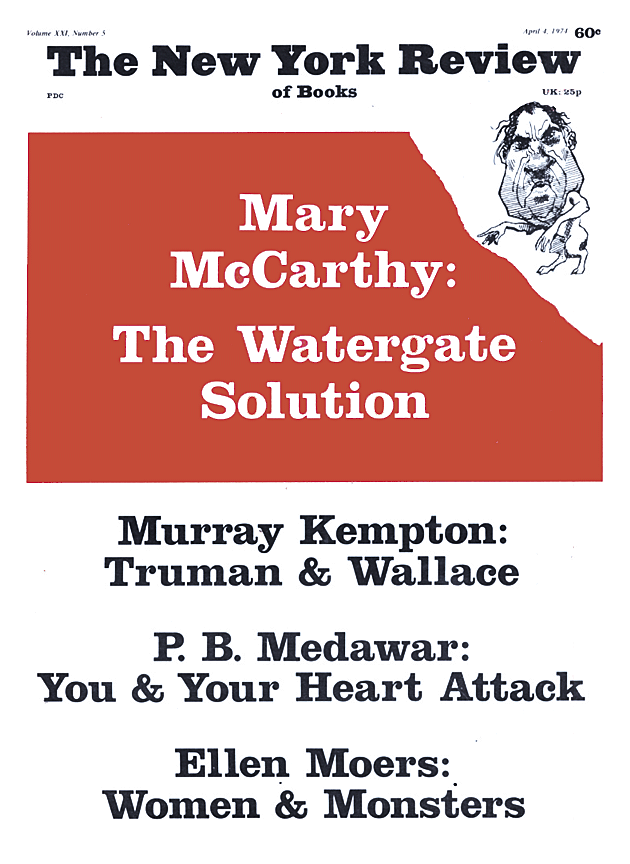

This Issue

April 4, 1974