In response to:

The Charm of Insolence from the November 14, 1974 issue

To the Editors:

The review of Gore Vidal’s Myron [NYR, November, 14] leaves us a bit puzzled. Perhaps Mr. Mazzocco’s inventive use of the English language is the source of the confusion, with his “irriguous” organ and “banausic” muse which go “havocking” about the western world. One cannot help being impressed with the critic’s way with words, especially adjectives, which he uses so often. For example, we discover that though Myron is a “vampiristic vaudeville, baroquely cadenced and cleverly done, it is (nevertheless) no match for the ineffable ease and raunchy simplicity of its predecessor,” Myra B. And while neither of us was around to experience “a translucent ’48,” we did manage to survive “a weltering ’73” without having ever been weltered. (From here, he goes on to state that “Vidal adds and pads at will.”)

Granted that the reviewer has a keen (or should we say “scrutinous”) eye for Hollywood trivia. Indeed, it is The Crusades and not The Crusaders. However, we fail to discover that the “apocryphal” film in which Myron finds himself was originally entitled Siren of Atlantis by United Artists and not Siren of Babylon by MGM. But no reason to be ashamed! So many of these little discrepancies keep popping up that it is hard to keep track of them all. Perhaps it is all part of some Plot.

It is clear that Mr. Mazzocco goes a few steps further than many other reviewers in that he had read the book, page by page. However, Mr. Vidal himself advises that unless one reads Myron line by line, one will miss the point. And so, the reviewer sees the parts well enough, but fails to grasp the whole. Myron is not a disjointed collection of inside jokes, but a sustained satirical performance. We do read that the novel juxtaposes the decline of the age of Hollywood with the decline of the age of television, but nowhere do we find that just as Myra is a creature of Hollywood at high noon, so is Myron the product of the video culture and its commercials, right down to his soon to be installed Miracle Mengers Powells. Also, the reviewer lacks an awareness of the technique of the novel (“if you keep notes about where you are, you can always figure out sooner or later where it is in relation to other things”—page 3) despite the alternation of sex and the concept of going back into time in order to change the present which is now the future; all adding up to the greatest (subtle) running gag of all, directed against the late model centipede novelists of France. He does, indeed, have a few insights about the satiric thrust against the macho mystique, and “the ideological cross-weavings of feminism and camp,” though he manages with some effort to forget all about them in the very next paragraph.

We find the review to be a comprehensive and rather helpful inventory of all the things reviewers are supposed to say about Vidal, with the “suave and exuberant,” “narcissistic smugness or intellectual hubris” and the inevitable comparisons to Petronius and Swift. Of course, we must throw in a few paragraphs about homosexuality (oops, bisexuality), even if it has little to do with the book. We must not fail to mention that despite Vidal’s patrician brilliance and savage wit, his books seem empty of the Human Element and have become Increasingly Bitter as the years go by. (Does anyone remember the original version of The City and the Pillar, we wonder.) We can rest assured, however, that this review will accomplish one thing, namely, that it will spare all future reviewers the labor of having to write out their own commentaries. All they will need is a scissors. We suppose that Myra would not object to that.

Steven Abbot

Thom Willenbecher

Allston, Massachusetts

Robert Mazzocco replies:

Thoreau says it’s really not worthwhile to go round the world to count the cats of Zanzibar and I suppose that’s what Abbott and Willenbecher (hereafter A&W for short) are accusing me of doing in my highly detailed review of Myron. But the point I was making is that the details are the point, that without them Vidal would not have had his book. For Myron, it seems to me, despite its audacity, is not “a sustained satirical performance,” is indeed, as a “whole,” a medley of bits and pieces, its hero far too sketchy a creation (the faltering “just folks” tone, the time-travel befuddlement) to significantly represent “a product of the video culture” or even Straightsville America, however uproariously intended. Whatever is good about Myron is much better in Myra B. And in Myron, I’m afraid, not much is that good or that subtle—merely complicated.

“The concept of going back into time in order to change the present which is now the future” is one of the oldest staples of sci-fi lit, which was around long before the nouveau roman, whose presence, as I suggested, is far more evident in Myra B. than in Myron. Calvino and Borges and their convoluted fables about space and time, Alice disappearing through the looking glass and changing into different shapes and sizes during the course of a day, the twentieth-century hero of Berkeley Square in an eighteenth-century world predicting events to come—these seem to me, again as previously stated, the more appropriate progenitors of Myron and its inventions, and not the “centipede novelists of France.”

“Irriguous” is an adjective meaning “moist” and the organ referred to is the vagina. The term “banausic” comes from philosophy and concerns “the illiberal or vulgar arts,” subjects with which Vidal has frequently dealt. A&W may not have been around to experience “a translucent ’48,” but the revelations of ’73 were, I imagine, “weltering” for many of us. These are, in any case, the book’s pivotal years, and Myra, who’s really its controlling center, regards them, in her highstrung way, exactly as I described them.

But if A&W have difficulty with my English, I must say I’ve some trouble digging their own. They’ll have to tell me, for example, how if one does indeed read a book page by page, one is not also reading it line by line, as well as word for word. And if Siren of Babylon was never made at MGM and Maria Montez never worked at MGM and if it’s therefore an “apocryphal” film, its only existence, in fact, being in the fiction called Myron, what then would it mean to add it “was originally entitled Siren of Atlantis by United Artists”? And if what I say about Vidal is familiar stuff, how then will “this review….spare all future reviewers the labor of having to write out their own commentaries”?

As far as I can gather, there are no “discrepancies” whatever—except one. The editors of The New York Review were so scrupulous about quoting material from Myron that they disregarded my typescript and perpetuated the incorrect spelling of Margaret Sullavan’s name, also misspelled in Myra B., also containing additional errors, which I’ll refrain from mentioning, of course, since they’re on the order of what-Maria-Ouspenskaya-said-to-the-Wolf-Man, or what A&W aptly call “Hollywood trivia,” so dismaying to them. But I will add I do prefer readers who scrutinize to those who scan. The “few insights” of mine about “the macho mystique” and “the ideological crossweavings of feminism and camp,” which with “some effort” I manage “to forget,” were there to describe the particular flavor of Myra B. In the sentence that follows I wrote: “Certainly nothing comparable exists in Myron.”

Two other matters remain. One has to do with sex. Naturally I think it a wonderful thing that Gore Vidal has so consistently and courageously spoken against the barbarify of a country where, as a poll of a few years ago demonstrated, a majority of Americans consider the “crime” of homosexuality to be worthy of capital punishment. Nevertheless my concern was not with Vidal as dragon slayer in a wild land, a role for which he’s justly celebrated, but rather how his attitude affects his sense of character and the imaginative worlds he constructs.

Sex is fluid, that’s its essence: it can take any form and find fulfillment in that form, it can assume any role and be that role. It is only the inhibitions of the mind, the circumstances of the moment that can turn the fluid dry. But it’s just these inhibitions, these circumstances with which so often we’re confronted—and that’s so, I’m afraid, even among the most sophisticated. Frankly in his fictions I don’t always feel Vidal is sufficiently attuned to or interested in the nuances, “the claws and wings,” as Nabokov puts it, of human relations. One difficulty, no doubt, is his elegance. Another his sense of humor. Both exemplify his charm. Yet both prohibit, I suspect, a certain emotional concentration—which is not quite the same as wearing one’s heart on one’s sleeve as he does, I believe, in The City and the Pillar, where the results, for the most part, are melodrama.

All that, though, is simply a matter of opinion. What’s not, I think, is A&W’s contention that I “throw in a few paragraphs about homosexuality (oops, bisexuality), even if it has little to do with the book.” But Myron, along with Myra B., reeks of libido. To suggest otherwise is like the defense attorneys at the Watergate trial asking the jury to disbelieve the evidence of their ears as they sit listening to the tapes.

The other matter, merely implied, concerns Vidal’s presumed critical neglect, or lack of deserved cultural recognition, probably because he suffers the taint of celebrity. Well, that is unjust. As for myself, however, I know I’ve read practically everything he’s published, consider him an important figure, and whatever the expressed reservations about his oeuvre, thought my admiration clear enough. To say of an author that he has written “a classic,” even if “of a sort,” that “as an essayist he is one of the most attractive writers America has produced,” and finally to compare him (and by no means unfavorably) with Swift—well, I would imagine praise of that order tempting indeed. But perhaps Gore Vidal is really not as vain as his umbrageous (adj. easily offended) communicants would have us suspect…

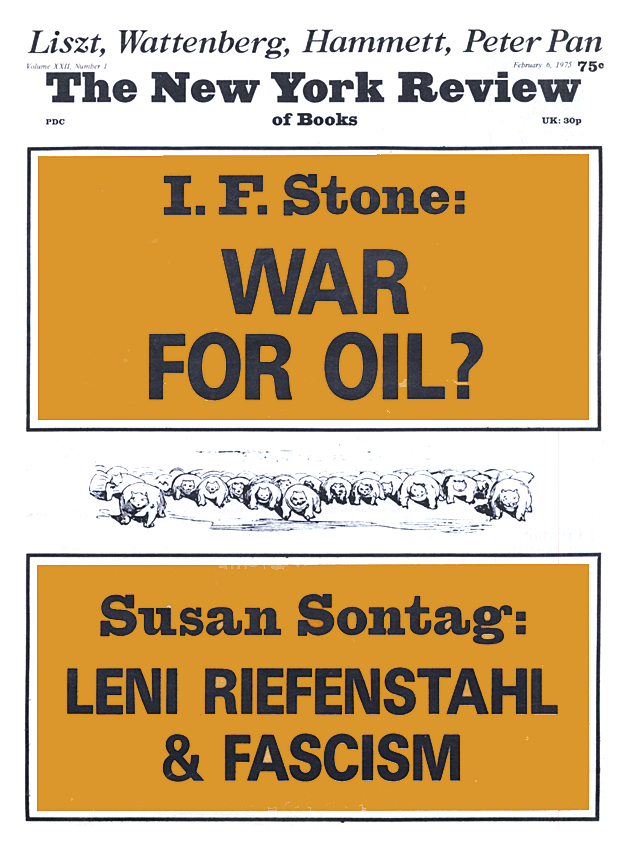

This Issue

February 6, 1975