In response to:

Disturbing, Fanatical, and Heroic from the November 13, 1975 issue

To the Editors:

Professor Leonard Schapiro’s review of Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago Two requires comment on several matters.

First, Schapiro overly stresses Solzhenitsyn’s concern for individual spiritual integrity as opposed to “materialist” values, a duality which is not nearly so cut-and-dried as Schapiro indicates. Indeed, one theme that does “run like a thread” through Solzhenitsyn’s writings is a veneration for engineers and technicians and a contempt for interference in their work by uninformed, ignorant bureaucrats and politicians. It is this politicization of science which Solzhenitsyn would blame for unthinking environmental (and human) destruction, not “the ‘marvels’ of science,” as Schapiro would have it. In fact, it could be argued that Solzhenitsyn’s tendency to disparage democracy stems, at least in part, from an elitist distaste for politicians elected by the populace making complex decisions that ought to be left in the competent hands of specialists and technocrats. This is a species of “materialism” with which the West is all too familiar.

Second, Schapiro is right to distinguish Solzhenitsyn from traditional Slavophiles, but he does so on the wrong grounds. Solzhenitsyn would refrain from condemning “all law” as Germanic and alien not only because he approves of legal protests among other sorts, but also because he does not consider “Germanism” alien to his own values. A strain of pro-Germanism pervades his work; compare, for example, the admiration of German military efficiency and orderliness in August 1914 with, say, Tolstoy’s savage derision of the Prussianization of the Russian general staff in War and Peace. Solzhenitsyn also ridicules the Russian military, for not being German enough!

Solzhenitsyn displays a deep ambivalence in his attitude toward Russian emulation of the West; he is not sure, for instance, whether to attribute the grandiose and murderous Belomor Canal project to Stalin’s rivalry with Peter the Great, the prototypical Westernizer, or with the “slaveowning Orient, from which Stalin derived almost everything in his life” (Gulag Two, p. 86). This ambivalence should not obscure from us his abiding faith in the benefits for his backward Russia of the application of Western technological rationality, through the agency of a scientific-engineering class freed from ideological impediments.

Third, Solzhenitsyn may or may not be an anti-Semite, but Schapiro’s apologetics are even more embarrassing in this regard than anything in Gulag. “Is he to be blamed for recording a fact of history,” Schapiro asks, referring to the “very disproportionately large number of Jews” (Schapiro’s words, not Solzhenitsyn’s) who were secret police agents? Not by Schapiro, evidently, especially since he mentions a “good” one who was a Jew, too. (Some of my best friends….) Schapiro minimizes Solzhenitsyn’s interest in a man’s nationality (then why mention it at all?), but cites his belief that “a Jewish Russian is different from an Orthodox Russian, with centuries of Russian tradition behind him.” (Do Russian Jews not have centuries of Russian tradition behind them?) Schapiro opines, “that is a long way from anti-Semitism.” No, not so long, and if Schapiro does not see this, he ought to recall that the Jew’s alienness and purported inability to identify with a nation’s traditions and consciousness has always been a staple of anti-Semitic propaganda, including that of the Russian Black Hundreds.

Finally, I agree with Schapiro on Solzhenitsyn’s importance and greatness as a writer and as a bearer of witness to Soviet cruelty (though not with such a fanatical contempt for disagreement as the review’s “everyone knows,” “now almost universally accepted” tone betrays). It is just because his work is of such compelling moral urgency that a reviewer ought not to be intimidated by his suffering to the point of explicitly surrendering all claims to critical evaluation (“who are we to argue with him?”). Such a tone may be appropriate in an article on Sholokhov in Literaturnaya Gazeta, but not here. Solzhenitsyn deserves a more serious, and less ideologically sycophantic, audience than that.

David N. Stern

New York City

Leonard Schapiro replies:

I am grateful to Professor Struve for the very interesting details which he has supplied on the fate of De Profundis. Actually, it was carelessness on my part, rather than ignorance, to have described this book as “immediately suppressed.” It was in part “published” by the printers by the act of throwing some copies into the street before the majority were suppressed. I was, I believe, the first to tell this story in the West in my article on Vekhi cited by me. Actually, the late Professor Becker who had one of the, I believe, two surviving copies in the West, very kindly lent me his copy when I was preparing the seminar paper which ultimately became the article in the Slavonic Review.

Mr. Stern’s prejudices are so formidable that I don’t think any useful purpose would be served by entering into argument with him. I will only observe that if he thinks I am “ideologically sycophantic” he would do well to re-read my article.

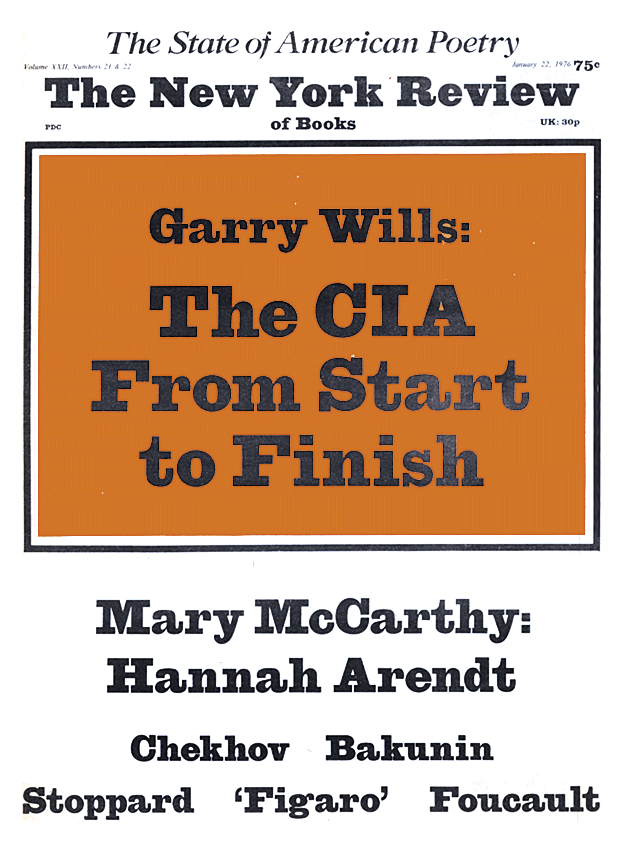

This Issue

January 22, 1976