“Weygand became Commander in Chief: he was 73. He tapped his briefcase, saying, ‘I have the secrets of Marshal Foch.’ The briefcase was empty. Weygand cancelled Gamelin’s instructions for a combined offensive, and….”

Only A. J. P. Taylor writes history like this. His highly curried style—dry, pungent, accompanied by astonishing little side dishes and, though no doubt wearing holes in the lining of the brain, impossible to stop consuming—becomes more concentrated every time he returns to topics which are familiar to him. And the Second World War is very familiar. As he says himself, “I have been composing this book for more than thirty years,” beginning as a lecturer traveling about wartime Britain to interpret the news week by week, and finishing with the books which have infuriated a fair number of academics and given violent pleasure to a much larger number of their students. The matter of this book has already been partially covered in The Origins of the Second World War (the real troublemaker, which proposed that Hitler might not have brought about the war deliberately), and in the latter part of English History 1914-1945, the last of the fifteen volumes of the Oxford History of England.

Emphases change, however. The landscape looks different to Professor Taylor every time he traverses it. Not totally different: the basic features of his view are still there. This was a conflict worth fighting, “justified in its aims and successful in accomplishing them. Despite all the killing and destruction which accompanied it, the Second World War was a good war.” Nevertheless, the perspective of thirty years since the war ended is not that of twenty-five years. The coherence of the period from the outbreak of the Spanish rebellion to the armistice of the cold war at Helsinki this year is easier to understand: more than the reign of Francisco Franco Bahamonde gives it unity as an epoch. Correspondingly, it is easier to link together into a single trench the various trial-pits sunk by revisionist historians along those years.

This time around, Professor Taylor is clearly becoming interested in the conservatism of the combatant states. On the last page of the Oxford History, he wrote: “This was a people’s war.” He meant only to observe that, in contrast to other wars, the British people themselves wanted to win. Now he is taking the idea much further. The war displayed two forms of conservatism in government motivation. There was the wish of the powers who were “more or less content with the world as it was” to restrain the powers who wanted to change it—Germany and Japan—and to restore something like the status quo ante. The Darlan episode was an illustration. The Allies set over the Algiers French this “persistent and virulent collaborator” as a sign that “the British and American governments wanted no change in Europe except that Hitler should disappear.” Secondly, there was the conservatism toward social change: specifically, the mistrust of the Allied governments toward Resistance and partisan movements which aspired to political as well as military aims.

A hundred years after 1848, another European “Springtime of the Nations” blackened on the bough as the cold war began. The Resistance movements, by no means as communist-dominated as propagandists still insinuate (even if that had been true, the example of Yugoslavia shows what happened to the loyalties of Stalinists who dared to liberate their own countries), were the most obvious expression of a revolutionary wave running across the continent, as a similar wave had risen in the closing years of the First World War. This time, the established states were better prepared. Stalin set about exterminating radicalism in his part of Europe, directing police terror first against the peasant reformers and the social democrats and then against the revolutionary idealists in the Communist parties themselves. The Anglo-Americans, comically promoting Stalin to the role of revolutionary incendiary, broke the Resistance movements of the West militarily and politically, and evicted most of their authentic representatives from the postwar governments.

In Italy, Professor Taylor observes, it was Field Marshal Alexander who ordered the partisans to demobilize. “This was an invitation to the Germans to move against the partisans…thus the Germans became implicitly the allies of the British and Americans, who feared revolution in Italy more than they feared the enemy.” The Special Operations Executive in London tried to restrict maquisards in Europe to recruiting support for the Allies and producing information, armed action being restrained until Allied regulars were approaching. The exception was Britain’s adoption of Tito, privately justified on the assumption that Yugoslavia was outside the known world anyway (“Are you going to live in Yugoslavia after the war?” Churchill asked an emissary who was uneasy about Tito. “No? Neither am I!”).

Taylor wrote off the Greek resistance as essentially communist in the Oxford History (1965); now he argues that it was not communist but radical and republican (“the British followed the German example and took armed action against a popular national movement…”). He storms at the Allied command for failing to use the French Resistance in western France properly, especially for ignoring the fact that during the Normandy fighting the Resistance had evicted the Germans from much of western France. “This was a political blunder of the first magnitude.” Here Professor Taylor trips over himself: if he is right in his basic insistance on the conservative, antirevolutionary approach of the Allied governments, then the Normandy omission was a military blunder but a political success.

Advertisement

With this new interest in Resistance aims goes a much more confident revisionism about the origins of the cold war than Professor Taylor has shown before. Stalin was not expansionist. His attitude toward Italy, France, China, and Yugoslavia during the war showed how little he wanted communist successes outside his own sphere; “it was he rather than the Americans who preserved Western Europe for capitalist democracy.” At Yalta, the West was not duped by Stalin but duped itself: it was obvious that Soviet influence would fill the vacuum of Eastern Europe and then proceed “to exclude anti-Communists from power as the West excluded Communists.” (This is a deliberately emotionless and even callous way of putting it. Taylor takes it for granted that his readers would never dream of equating the butcher’s bill of Stalinism in postwar Europe with the comparatively modest blacklists of the Western European anticommunists. The temptation to puncture an assumption—even a fair one—is too much for him, as usual.) The cold war, whose consequence was the imposition of full Stalinist control over the Eastern satellites, was a gigantic false alarm about the respective intentions of the two sides; an alarm made more intense in the West by the sense of impotent remorse over Stalin’s activities. He was not, after all, violating agreements: the West had licensed his sphere of influence during the war. He was a wartime bride whose charms turn to monstrosities when the GI gets home and pulls out her picture again. How could I have? “Allied co-operation did not break down because of the Yalta agreements; it broke down because the British and the Americans repudiated them.”

Hitler, once more, is argued to have been a mere gambler, devoid of any organized intention to bring about a European war, let alone a world war. “His aim was no doubt clear: to transform Germany into a world power. The means were to be provided by events…. Hitler lost, as someone has to do in war, and has therefore been written off as a psychopath.” It’s accepted now that there is much in this Taylor thesis—far from everything, though—but it comes out here with an unhealthy fluency, as if the sphincter on the Professor’s pen were giving way. Not everyone who thinks the war was Hitler’s fault is a player of the Great Ball Game and diagnoses manic aggressiveness owing to the lack of a testicle. On the contrary, if we accept that Hitler did not plan the European war in advance (and the Hossbach Memorandum, prima-facie evidence that he did, is not mentioned in this book), then we are entitled to say that the lousiness of his gambling was unpardonable.

Montgomery takes a battering. This is odd, because Taylor repeats his previous assertion that he was the greatest British field commander since Wellington and because Monty personified a way of making war with meticulous preparation and professionalism which Taylor fervently admires. However, Professor Taylor seems to get tired of him as the book proceeds, and promotes General Slim on page 210 to “the ablest British leader of the Second World War.” He adds a schema for the typical Monty battle—failed frontal attack, successful outflank, mendacious communiqué that this was all according to plan, and failed pursuit—which will make many old gentlemen in the United States happy.

The whole book is perhaps masterful rather than masterly. Gaudy beads of anecdote roll about among the hypotheses, the pocket contents of a historian’s trousers. Weygand’s briefcase was empty, Hungary signed peace on the table where Robespierre lay wounded before his execution, Slovakia stayed neutral throughout the war: these are lively little surprises. There are also some mistakes. The Americans did not sink all four Japanese carriers at Midway in five minutes: as the sketch map shows, it took twenty hours until the last of the four foundered. The Polish communists were not simply “Russian agents,” and to say about the Katyn massacres that “4000 dead did not weigh heavily against the six million Poles murdered by the Germans” is a fundamental psychological error (the mirror-mistake to his remark that the massacre at Oradour-sur-Glane was “one of the worst crimes of the war,” ignoring the dozens of larger Oradours in Poland and Russia).

Advertisement

This is an “illustrated history.” In fact, the text is brilliant and the pictures nothing very special, intelligently selected but ancillary to the writing. Of the photographs, paintings, and posters, the most moving item is perhaps a simple picture of a crushed aircraft-carcass in the jungle, a bulk among the indifferent leaves. This is “the tomb of Yamamoto,” a commander much admired by Taylor as a chivalrous strategic genius: “the Hector of the Second World War.”

In The Second World War, the illustrations illustrate, and are not the subject of study. WW II, a much larger picture book, seems to have set out to be an anthology of war art, principally American with a few unattributed Japanese and German paintings. It has turned out differently. The text by James Jones is a rambling structure which is sometimes a second-rate and eccentric narrative of the war, sometimes a discussion of the illustrations themselves and their accuracy, and sometimes—far the most interesting sections—Jones himself trying to get across the experience of battle for the fighting soldier.

The result is a halfhearted muddle. The Second World War produced exceedingly little graphic art or painting of any quality. America was no exception. The official war artists, soon taken over by Life magazine, produced some echoes of Goya and a few curious examples of a Norman Rockwell style scared into surrealism by psychic pressures of battle. The excellence of the American camera tradition probably quelled them. There is nothing here to compare with Henry Moore’s drawings of the London Tube, with Topolski’s great Russia at War, with Paul Nash.

James Jones tries vaguely to explain the selection by dismissing British war art as “very British,” the German work as lifeless, and omitting any reference to what was done in other countries save Japan. Art Weithas, who was the “graphics director” for the book, stays silent on the principles of his choice. The best pictures are some of the pseudo-traditional Japanese combat graphics, and a single, precious page devoted to “Nose Art,” the paintings which adorned the noses of aircraft. A big, full-color album of Nose Art would earn its $25 by recalling something spontaneous and exuberant, the expression of the aircrews themselves.

James Jones fought with the Twenty-fifth Infantry Division in Guadalcanal. He survived much battle, was hit and recovered, and finally, in the idiotic manner of war, was invalided home because he had twisted his ankle. In this book, apart from wasting time trying to recount the course of war (the Soviet Union, which defeated Hitler, receives four perfunctory mentions, two of them rude), he tries to explain the evolution of a soldier.

By this he means the mystery of why men stay around to be shot at, continue to stay around after they have experienced the consequences of being shot at, and in some cases come to regard being shot at as a way of existence with certain attractions. Europeans, as James Jones says, find it harder to regard this as mysterious. The Duke of Wellington, finding a regiment at Waterloo lying flat on its belly to escape a grapeshot barrage, roared: “Dammit all, forty-second, d’ye want to live for ever?” Jones is trying to explain why they stood up.

The combat soldier “must make a compact with himself or with Fate that he is lost. Only then can he function as he ought to function under fire.” Acceptance that he is lost admits the soldier to a curious, detached world. Sensations are heightened: “everything tastes better.” Watching other units “get theirs” conveys a simple pleasure, not exactly sadistic. Recalling that feeling, Jones writes: “It was just that we had nothing further to worry about. We were dead.”

James Jones calls this a professional attitude to soldiering. It is not. It is the self-defense of the citizen conscript, from a nation never threatened by foreign conquest whose best traditions regard peace as permanent and normal, and military discipline as unconstitutional and ludicrous. No sane officer wants to command men who regard themselves as dead, in case they smoke pot, frag him, or refuse orders. My own sergeant’s view was that anyone who got hit or killed was culpable, and his remains should be charged with offenses prejudicial to military discipline. This frightened us all greatly, usually more than the enemy did. It was crazy, but it was more professional than fatalism, let alone heroics. What Jones is saying, with difficulty but much force, is that some situations are so bad that leadership and conventional morale no longer matter.

And for the survivors, the “de-evolution” of the soldier into peace was almost as hard, and lonelier. Good Housekeeping magazine, he recalls, told the wives: “After two or three weeks he should be finished with talking, with oppressive remembering. If he still goes over the same stories, reveals the same emotions, you had best consult a psychiatrist. This condition is neurotic.” So ended the People’s War.

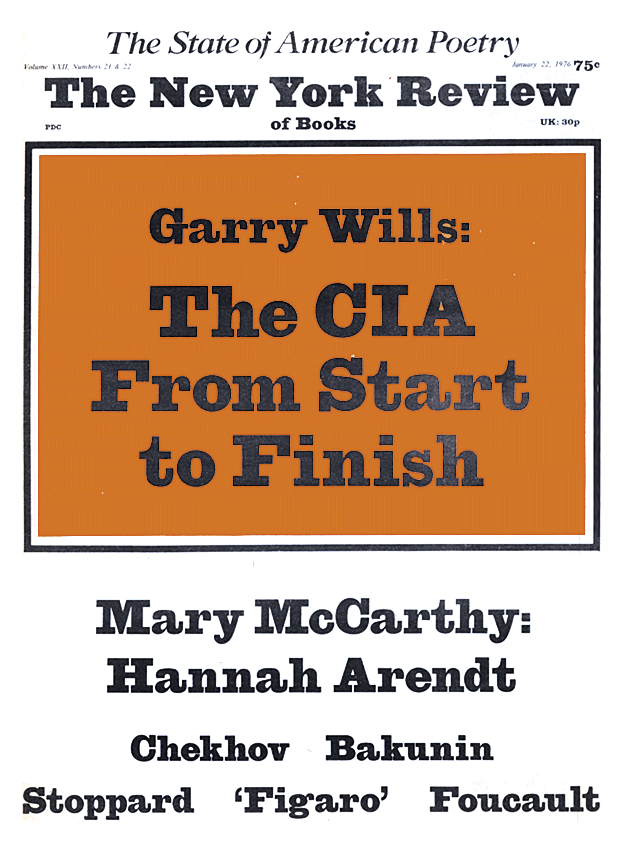

This Issue

January 22, 1976