These three books about Sylvia Plath have all been coming out within the space of a few months. They are not the first books on this subject, and they will not be the last. Ever since her death in 1963 she has been the goddess of a cult, whose homage has tended, in a romantic spirit, to represent her as a victim of the hard world that poets must inhabit: more recently, and less disarmingly, it has also tended to represent her as a victim of the cruelties and deprivations to which women have been subjected by the supremacy of the male. When her former husband, the poet Ted Hughes, appears in public, women yell abuse at him, ask how Sylvia is keeping, and ask about her suicide. There’s a woman’s poem which refers to Ted’s friend and Sylvia’s rival, Assia Gutman, who also committed suicide: “Hughes has one more gassed out life on his mind.”

Such displays, which are part of a new barbarism to which Western societies have become accustomed, will not be cut short by these books, if only because books have comparatively little to do with the matter. Sylvia Plath was amused that English boys should think of her as “a second Virginia Woolf,” and Virginia Woolf, to whom she felt “very akin,” has lately been taken up in the same way, by the same sort of people: the realities of the relationship between each woman and the man who loved her have been violently abridged or drowned in anathema.

I shall look at the three books mainly from a biographical point of view. Ms. Kroll is opposed to the biographical approach to Plath’s work, which is assimilated in her book to mythic patterns, and construed as swept up, in the end, into a flight from biography, a bid for transcendence. For that reason among others, the book can be considered very interesting biographically. Sylvia was born in Massachusetts in 1932, the daughter of Otto and Aurelia Plath, who were respectively of German and Austrian stock. If she was a “second-generation achiever”—an expression Edward Butscher makes use of—then her parents were achievers too.

Otto was a biologist and an expert on bumblebees, which were later to buzz in his daughter’s bonnet. Aurelia, who had been his pupil, went on to become a teacher herself. In Letters Home, she explains that her husband grew hypochondriacal, a briefcased recluse, who declined to go to doctors, though ailing and seeming to feel he had cancer. By the time diabetes was diagnosed it was too late to save him, and in 1940, having lost a leg, he suffered a pulmonary embolism and died. Sylvia was eight. Two years later the mother and her two children moved to Wellesley. What it cost her to enable the family to survive and prosper is something that Aurelia has perhaps found it difficult to assess, though it is clear that biographers will be ready to enlighten her.

Sylvia loved it at Smith—“as I always sit in the middle seat in the front row, it seems as if Mrs. Kafka is talking directly to me”—and she achieved a great deal there, including a holiday stint on Mademoiselle in New York, which she was to write about in her novel The Bell Jar, and from which she returned to perform a suicide attempt, in August 1953, taking pills and retreating to the shadows of a “crawl space” under her mother’s house. She was retrieved, hospitalized, and given electric-shock therapy. In England, at Cambridge, she met and married Hughes, gloried in that marriage, had two children by him and lived with him, mostly in the West Country, for some six years. In 1962 she discovered that her husband had formed a friendship with Assia Gutman, and the marriage broke up.

She was now in the phase during which practically all her important verse was written. These must have been months of the utmost strain. She took responsibility, not only for her poems, but for her children, and for a move to London, where, on February 11, 1963, she ended her life. “We have come so far, it is over.” “Sylvia died today,” said Ted Hughes in a telegram to America. For a while, Aurelia was unable to believe, or at any rate to acknowledge, that her daughter had committed suicide.

This is a story which is told only very indistinctly in Sylvia Plath’s letters and in her mother’s commentary on those letters. Was she as agonizingly intent on prizes and places, as deeply captured by a fear of less than perfect marks, as this volume discloses, while also disclosing a bright, achieving domesticity? Her mother is apparent as “Dame Kindness” in a poem which is as much about herself, and her own kindness, and human-kindness, as it is about her mother: were the tendings of Dame Kindness repaid in kind?

Advertisement

No one would expect an absolute candor from anyone’s letters home. Omissions are marked in the published text, moreover, and cuts were conceded (and refused) to Ted Hughes, who owned the literary rights. He has as his agent his strong-minded sister, Olwyn. Olwyn and Sylvia seem to have angered each other over the question of who stood closer to Ted, and on one occasion Sylvia fled from a quarrel, at a witching hour, out onto the Yorkshire heath, as if in the general direction of Wuthering Heights. Olwyn is for ever being thanked for kindnesses by writers about Plath: this is scarcely like praising the Eumenides, but it is probable that some of these writers have experienced a sense of constraint in describing and documenting events which have survivors—survivors with a very natural interest in what is to be said about themselves.

At the same time, we may not really need to bother about lacunae in examining the insufficiency of Letters Home. Aurelia Plath does not disguise her concern to sugar her daughter’s strange history by producing her fond and normal letters. The commentary has it that she died of overintensity, strain, and that the suicide attempt of 1953 had been caused, or strongly conditioned, by disappointment at being denied a place in Frank O’Connor’s creative-writing class. Aurelia says of her daughter’s “life-experience” that, in 1963, “some darker day than usual had temporarily made it seem impossible to pursue.” Sylvia’s patron, Olive Higgins Prouty—cultivated upperclass women are apt to have three names in the commentary—is quoted as warning: “A lamp turned too high might shatter its chimney.”

Neither the commentary nor the letters enlarge on the poet’s feelings about her dead father, which have often been regarded as the source of her breakdowns, and of her double or multiple personality. Sylvia Plath could show herself to observers and readers as alternately benign and hostile, as Snow White and Old Yellow—to borrow terms from interpretations of her work—as the possessor of true and false selves. And if we accept that there were several selves, we might also accept that only one of them is on show in her letters home.

It might be said, therefore, that the letters are bent on withholding her “true” condition. “Starless and fatherless, a dark water”: I remember seeing these and other late lines in typescript soon after they were written, and feeling that she needed help, that they were the truth. Hers was an orphan state, and as with other Romantics, it is possible to feel that she had chosen that state, while also being chosen by it, and had invented that truth. These procedures could not have been made known to her mother, and her own conduct was often to appear to disown them.

Plath saw herself as “adoring and despising” her father, whose death made her feel both bereaved and guilty. She may have imagined herself betrayed by his departure, which could have been experienced as suicidal, and she needed to exorcise him, as she proceeds to do in her ritualistic poem “Daddy.” Ambivalent feelings toward her mother, too, ensued, and she is awarded a hard time in the “Dame Kindness” poem. Equally, emotions about her father could coincide with what she felt about her husband. As I say, this drama is excluded from the letters: here, wholly acceptable, she is Miss Kindness, and Miss Success.

The fatherless Plaths’ fight against poverty and failure meant that Sylvia could seem, as in the letters, morbidly ambitious, battering down the women’s magazines: “I will slave and slave until I break into those slicks.” Success, however, though a momentous and perilous business, had to wear a smiling face, had to drink and offer cups of tea, and conspire with her mother to deny the existence of hostility. Kroll follows Sylvia Plath into William James’s varieties of religious experience, and suggests that Sylvia worshipped, and was, the white goddess of poetry. For James, there was a further variety of experience available to Americans, which he identified with the worship of the bitch goddess of success. In Sylvia Plath’s case, both worships could be dissembled in domesticity.

“Dearest one,” she wrote to her mother on March 3, 1953,

…The dress is hanging up in my window in all its silvern glory, and there is a definite rosy cast to the skirt (no, it’s not just my attitude!). Today I had my too-long hair trimmed just right for a smooth pageboy, and I got, for $12.95, the most classic pair of silver closed pumps…. With my rhinestone earrings and necklace, I should look like a silver princess—or feel like one, anyway. I just hope I get to be a Junior Phi Bete this year so I can use it for my Phi Bete dress, too. (Do you realize that I got the ONLY A in the unit from Mr. Patch!)

…God, how I wish I could win the Mlle contest. This year would be so ideal while I’m still in touch with college…. Bye for a while, Your busy loving, silvershod Sivvy

What can there have been to excise from that particular letter? Later in the month she tells of receiving rejection slips: she once said she had hundreds—“they show me I try.” She wants to “hit” The New Yorker with her poems and The Ladies’ Home Journal with her stories. She hears “the great W.H. Auden” speak in chapel. April is kinder: elected editor of the Smith Review. Then there’s the text of a telegram, announcing her guest editorship at Mademoiselle. The excitements of her spell on the magazine are despised in The Bell Jar, and described there by means of a successful approximation to Salinger’s wit and sophistication which no more resembles the self of her late poems than it does that of her letters home. In the letters, these excitements amount to glamorous fun. But they helped to thrust her into that crawl space.

Advertisement

Edward Butscher seems sure that, with more than one of her selves, she hated her “dearest one.” In the words of On the Waterfront, a film of Sylvia’s heyday, he declares that theirs was “an unhealthy relationship.” He has written a breezy, knowing, and sometimes sensible book. He is critical of her, and clinical, and he spends so much time expressing dissatisfaction with her earlier verse that he may have run out of patience when he turned to the “terrific stuff,” as she called it, which “will make my name.” He has interviewed a large number of people who were willing to supply memories, so that his book abounds in dates, double dates, blind dates, necking, petting, sitting in cars, period pains, chilblains. What friends have to say won’t invariably be true or interesting: a schoolteacher of hers “mentioned a vague memory of Sylvia having suggested in a letter to him that Ted was a little too sexually aggressive for her.”

Every so often, Mr. Butscher comes across as a researcher who researches into gossip, and none too persistently at that. He might well have removed a few memories to leave room for discussion of a piece which Plath herself wrote for The New Statesman after her separation from Hughes: a review of Lord Byron’s Wife by Malcolm Elwin, a book which she said in a letter she was lucky to receive and had wanted to get her hands on, though it may have been sent (by me) in ignorance of quite why this might have been so. “Mr. Elwin begins, as might many a shrewd marriage counsellor, with a meticulous investigation of the bride’s mother.” Byron’s wife Annabella and his sister Augusta were confronted with Byron’s “crude incestuousness.” “What surprises”—perhaps it’s her Wellesley self that is surprised—“is the fabulous malleability of the two women.” The review concludes: “How clearly one sees the killing dybbuk of self-righteousness in possession! And what better luck this cherished, sympathetic sister might have had as Byron’s wife.”

This Wellesley self made a talented, highly acceptable reviewer. Here is the brave face of someone who did not want to be like Annabella Milbanke. In skillfully endearing herself to her readership, she preserves a composure which has in it the marble of certain of her last poems, so that the review is not unlike one of the effigies of herself with which she said goodbye.

At Smith, a contest for supremacy occurred between Sylvia, the good girl, and “Gloria Brown,” a bohemian radical who drank rum. Sylvia threatened to inform the authorities of this habit. When Commencement Day arrived, Mrs. Plath, suffering from an ulcer, had to be carried on a litter to watch her daughter being awarded her summa cum laude certificate, while her daughter was laid low by stomach cramps and had to borrow, for medicinal purposes, some of Gloria’s rum. Sylvia wrote her enemy a note: “Thank you for teaching me humility.” The episode is related in an excellent memoir of Plath by Nancy Hunter Steiner, A Closer Look at Ariel, and Butscher hasn’t much to add. Gloria does not seem to have been interviewed.

I must say, though, that the testimonies of those who knew the Hugheses at Cambridge University are worth reading for what they reveal of the farcical side of one of those worlds of respectability and culture which Plath intended to penetrate, and which she has posthumously subdued. The Cambridge of 1956 could be idyllic: “Dear Ted took me for a walk in the still, empty Clare gardens by the Cam, with the late gold and green and the dewy freshness of Eden.” Yet “Eden is, in effect, helping murder the Hungarians.” This other Eden was the prime minister, who, the Russians having invaded Hungary, had invaded Egypt.

Cambridge could also seem cold, and its dons crass and inky. It is easy to see what she means when these dons testify. Miss Burton, her director of studies, remarks of Plath’s marriage: “I do remember A.P. Rossiter, the late medieval and renaissance writer, saying of her husband, ‘I wish he could learn to keep his hands out of the placards,’ which didn’t suggest to me that Ted was exactly concentrated on Sylvia.” Mr. Butscher should surely have written “plackets,” not “placards” (and this seems the place to mention that the couple can’t have been married on “Bloomsbury Day,” June 16, though I imagine that Virginia Woolf and company will soon be inspiring new ventures in commemoration).

Miss Burton becomes still more offensive. Ted was “a slightly gangling, not altogether couth type, who was certainly tough.” The marriage was odd “because Ted, at that stage, was very definitely a provincial, while Sylvia had a very wide range of European culture and was totally civilized. She could have passed anywhere without putting a foot wrong, and I was quite sure Ted couldn’t.”

Another don, Miss Pitt, thought the marriage equally odd: Sylvia “told me one extraordinary story about Mr. Hughes smashing the top from a bottle of wine and drinking from it…the fierceness implied in her account of this was something I was well able to believe since I had just encountered Mr. Hughes at a party given by one of my students and attended by a group of rather wild young men, whom I was assured were Irish and poets. At the point at which one of them was gesticulating and appeared about to embrace the late Morgan Forster, I left; the party was later raided by the Proctors.” The union of Heathcliff and Catherine, or of Marlon Brando and Eva Marie Saint, was not the kind of thing that these ladies liked to witness, just as Miss Pitt would never have been party to an act of necrophilia.

Judith Kroll is ingenious and determined. Many of her findings have been checked with Ted Hughes, and it is evident that the two of them are keen to draw Plath’s verse as far as possible beyond the reach of exploitative biographers and of those critics who treat it as “confessional,” like Lowell’s or Anne Sexton’s. Plath was undoubtedly responsive to the confessional vein of her time, and said as much. But, says Hughes, it is in a “radiant, visionary light” that she meets the realities of her domestic life. Her poems, then, are not autobiographical. They are not what she herself called “cries from the heart” about “a needle or a knife.” They express the vision of a “mythic totality,” says Kroll, who can give the impression of studying the images and deciding that the only ones that count are those which can be related to the canon of books where the parent myths are expounded. Dictionaries, classical concordances are regularly consulted. Though no one would think it an especially autobiographical poem, “Totem” is dealt with here in a way which illustrates the governing impulse to get rid of autobiography:

These and many other details from private life clearly do not enter into the meaning of “Totem.” Instead, the personal level fuels the impersonal, providing concrete images which express the most universal themes, even as they are private emblems of what drives her to investigate such themes. The private is not the ultimate level of meaning but part of something extraneous to the poem which nevertheless helped make a successful poem possible.

The language breaks down in struggling to convey that the poem uses private material which both is and is not extraneous. The writer needs to be told that, in general, there can be no poetry where there is no private life, though this doesn’t have to be a matter of knives and needles.

The book states that the poems see father and husband as surrogates for one another, and that a conflict between true and false selves is acted out in relation to the male. The male has subjected the true self to a death-in-life, and the true self longs to die and be reborn. The principal motifs of the poetry, therefore, are the male as god and devil, the true and false selves, death and rebirth. “The protagonist, rejected by her personal ‘god,’ characteristically attempts to resolve the resultant death-in-life by transforming him into (or exposing him as) a devil or similar figure as a basis for rejecting him.” Shortly afterward she writes: “Either the false self or the male (or both) must be killed to allow rebirth of the true self.”

For all that it has to say about the impersonal and the elemental and the eternal, this mythic scheme can look like the story of Sylvia Plath’s life, as told, perhaps, by a female chauvinist. I am persuaded that she believed in these myths to some extent, and her use of them can be accounted part of the autobiography of a woman who could at times fear childbirth and feel hostile toward men, who could wish to escape from her home in order to write verse, who could wish to escape from biography altogether, a woman who kept cheerful but could also act the witch and bitch, and who, with plenty of dates, was something of a vestal virgin, as her first name might suggest. It suggests this to Ms. Kroll, who is attentive to meaningful names: Plath’s story is rich in these, though it may not matter very much that Olwen is a Welsh name for the anti-domestic White Goddess.

Kroll’s scheme is established on the basis of a comparison between the poems and certain books which the poet read: chiefly, Robert Graves’s The White Goddess, Frazer’s The Golden Bough, and the writings of Jung. So we hear about the art and magic consecrated to the White Goddess, about her votaries, about maenads, about the Moon-muse. Graves’s Old Sow of Maenawr Penardd, among other witches, replaces the bitch goddess contributed by James to the Plath pantheon spoken of by Mr. Butscher. We hear about the dying god, about the divine king killed in order to secure the future. We hear about ecstasy, and about its etymology.

But that is not the end of Judith Kroll’s contentions. She affirms that in her last days Sylvia Plath passed beyond such conceptions of mythic rebirth, by experiencing a religious crisis or conversion. Personal history was to be transcended in a more radical way than that implied in the previous doctrines. It is in this context that her suicide must be understood. We are to suppose that the poet may have said to herself what the Roman emperor is supposed to have said (if vague memory serves) on his deathbed: “I think I am turning into a god.”

For many years she worked hard at prize and apprentice poems, as they could often seem, learning as she did so from Stevens, from Dylan Thomas. She then gained a poetry of a different order, a poetry which carried the formidable subject-matter of a second severance from the divine male. She proceeded to repeat, and to reconstitute, that severance by conducting a species of exorcism. For the purpose of such rituals, her parents and husband could be made baleful: but Kroll is aware that this is not all that they were to her, even then.

It may be that the new poetry can be found, coming into force in, “The Moon and the Yew Tree”:

The moon is no door. It is a face in its own right,

White as a knuckle and terribly upset.

The poem appears to have been written as an exercise in 1961, when the Hugheses were still together, but the words “terribly upset,” which are the words of speech to a degree that few of her earlier words ever were, signal a change. D.H. Lawrence, and Blake, may have assisted the change. The “Ach, du” addressed to her Daddy in the fine poem of that name is speech too, intensely expressive speech, and it sends out the same signal. She is down off her stilts, off her New Yorker stool. The reader shares in the intimacy communicated by these words. A number of the late poems were written down at top speed, like letters. She was released.

Judith Kroll’s explanations can help one to figure out poems that often prove as difficult as they are shapely and translucent. But she pushes these explanations into debatable ground. At an earlier stage of her life Sylvia declared that she did not believe in personal immortality, and I am left wondering what it is that she would have to have believed in in order to write and act as she is alleged to do here. Ted Hughes has testified that a religious crisis took place, but the question of how such a thing could validate an intentional suicide, if that is what we have to reckon with and if validation is at issue, is one that we could not hope to settle unless we came to know much more about her death than we do now. Literary critics frequently tell you, with relish, that the experience of the mystic is incommunicable, and then go on to tell you about it. Ms. Kroll is like that. Most of the ideas she explains have the character of superstition: only a believer could believe them. Is she a believer?

Some of her explanations seem arbitrary when placed beside the verse: they do not always manage to decode poems which, if her explanations are right, must hitherto have been perceived as cryptic, rather than merely difficult. One of the images for breakdown which Plath employs is that of confinement within glass, as in a bell-jar, and Kroll relates this to the White Goddess myth whereby Snow White, who is immortal and need endure only a mock-death, is laid in a glass coffin. There is a connection, but there is also a difference, which is not unlike the difference between pessimism and hope. A similar point arises with “Paralytic,” a poem which is taken to mean that the loss of certain faculties might ensure a joyful transcendence: this implies a highly provisional view of paralysis, hough I accept that there are hints of such a meaning in the poem.

According to the mythic scheme, the color white can be both good and bad, and so can the influence of the Moon. Plath’s moons are not easy to interpret, and the White Goddess lore is both useful and not useful. In “The Moon and the Yew Tree,” “the moon is my mother,” who “sees nothing” of her daughter’s fall, or of her inability to believe in the consolations of a maternal religion. To be content with this poem it would not be necessary to notice an attachment to the White Goddess. In “Edge,” written in the last week of her life, she looks down at her own dead body, that of a “perfected” woman. Her children have been delivered back into that effigy.

The moon has nothing to be sad about,

Staring from her hood of bone.She is used to this sort of thing.

Her blacks crackle and drag.

Here again, the Moon ignores the spectacle below. That closing line is less cryptic if you learn that a cauldron is the emblem of the Moon Goddess: flames might crackle beneath such a pot. And the Moon’s blacks might be said to drag from them the blood of menstruating women, or that of women poets. In another poem, perfection is linked to barrenness, and that thought may be present here too. Ms. Kroll has a footnote which observes: “A description of the Moon card in a Tarot book owned by Plath might be compared with the import of the Moon in ‘Edge.”‘ But the description refers to sweet peace and voluptuous dreams—and fails to fit. Sweet peace does not crackle and drag.

Poetry is blood in the “Dame Kindness” poem, which ends:

The blood jet is poetry,

There is no stopping it.

You hand me two children, two roses.

This poem and “Edge” combine to say that poetry abolishes domesticity. But Sylvia had more than one view of domesticity. In May 1953, she wrote to her brother about what their mother had done for them: “After extracting her life blood and care for 20 years, we should start bringing in big dividends of joy for her.” This might be interpreted as the voice of her false self: but we should recognize that to do so would be to attempt to deny what her mother, who protected her for twenty years and had much in common with her, took her to be. Those who think that this self did not write poetry should glance at the opening line of a birth poem: “Love set you going like a fat gold watch.”

Poetry is detail, as well as blood. In two of these poems, perhaps, her children are roses, but the closing line of “Kindness” has been taken to allude also to two real roses given by Ted Hughes—I am uncertain to whom—and written and dreamed about by him. Biography, including the biography inherent in her use of myth, can sometimes appear to overwork and disturb her poems, producing a certain blankness of effect, in which detail ceases to contribute: as on this occasion, when the two roses may well be meant to contribute something of importance. Her moons and her roses, and her color scheme, usually make poetic sense—the “heart-rending sense” which Graves himself required of poetry: but there are important occasions when they do not do this.

Is Aurelia Plath’s account of her daughter’s death, in so far as it relates to the immediate circumstances, less satisfactory than Judith Kroll’s religious one, or than the elaborately psychiatric ones? Perhaps the most striking testimony in the three books is that of a woman friend who said, in effect, that no one cared tuppence about Sylvia because they felt that she did not care about anyone—anyone beyond her family. This is an exaggeration, in the free-and-easy manner of such testimony. But I can see why it was cited, and it has a bearing on her final predicament. Almost alone, though still in touch with her husband, fighting for her children and for a place to live, spent from the hemorrhage that had gone into the poems that made her name, twice bitten—or eaten, to use one of her own expressions—in the very place where she had been afflicted before: her predicament had to be—to use one of Mr. Butscher’s expressions—very taxing. It would not be surprising if at one point she lost hope, and either sought or risked her death.

In the days when madness was popular, “confessional” poetry was welcomed because it could appear to be a celebration of madness: a similar welcome was extended to the Gothic literature of the nineteenth century, with which Sylvia, who knew about dybbuks, was in sympathy. She herself, though she has been admired for falling into madness, and for all her rival or successive selves, was sane. And because I think she was sane, I do not think she believed, to the extent that Judith Kroll supposes, in the myths presented in that author’s book, with their content of murders and curses, or that she died of an apotheosis in the form of a desire for transcendence. In her last days, despite the exorcisms and “witchy” behavior embraced and enacted in her verse, she could resolve to act generously toward her husband and to make new friends. Was this a false self or start? Connoisseurs of the deathliness of her true self would call it that.

It is presumptuous to talk about this subject, but others have preceded me, and I have agreed (with misgivings) to review these books. In The Savage God, A. Alvarez suggests that her suicide was a gamble by a natural risk-taker who stood a fairly good chance of being rescued, and that it was a cry for help. To the second of his suggestions, setting aside the first, I would want to add that it is possible to think of her as dying of her poetry, and of the troubles that filled it, and of an inherited anxious ambition: it is possible to think that the life went out of her with her sting. Keats said that poetry, with its feeling for contrast, for light and shade, was written on the stomach, and was, in cases of illness, the great enemy of the recovery of the stomach. He too, though he would have died anyway, may be thought to have died of his best work.

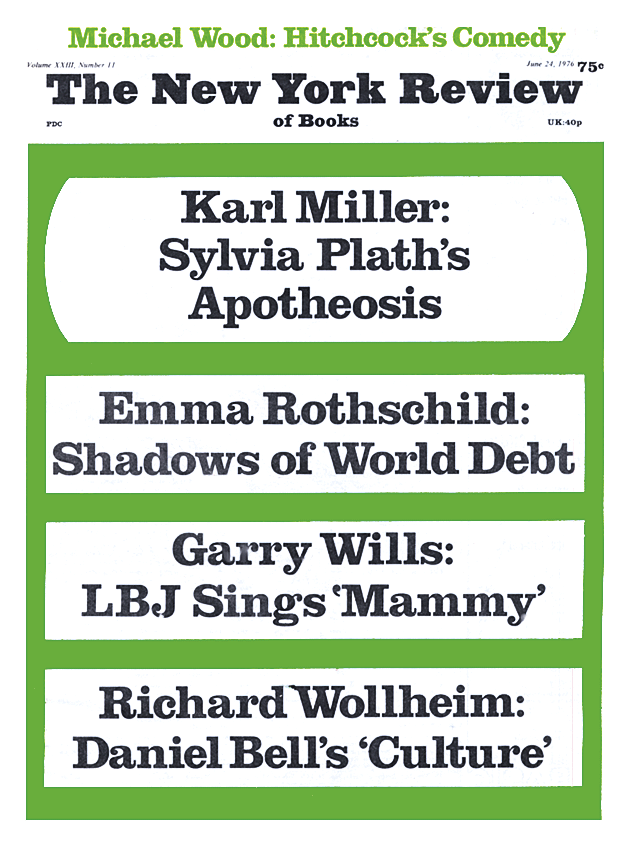

This Issue

June 24, 1976