I

There is perhaps a slight element of prejudice in the opinion, widespread among us Piedmontese, that San Gennaro and Giambattista Vico must be left to the Neapolitans. This opinion is indeed prejudiced in so far as it does not take into account that both San Gennaro and Vico have proved embarrassing to educated Neapolitans, and more especially to the descendants of those lawyers who in the eighteenth century came down from the provinces to Naples to fill high positions in the administration and who embodied the Enlightenment.

Benedetto Croce and Fausto Nicolini, the scions of two such Abruzzese families (as Nicolini was fond of recollecting), are exactly a case in point. To be the historians of Naples, and more specifically the interpreters and editors of Vico, they had to come to terms both with the saint of the plebeians and with the plebeian philosopher who had understood the fancies of the “bestioni” so well. As for San Gennaro, it was simple enough. Croce expressed his sympathy for a popular Catholicism which in his judgment was more meaningful than the Catholicism of the theologians and did not claim the approval of the educated: see his essays in Uomini e cose della Vecchia Italia II (1927) and Varietà di storia letteraria e civile II (1949).

Vico was of course more difficult, as one can see from the extensive work on him that Croce and Nicolini produced during a period of some forty years. Vico stuck to Catholicism, kept sacred and profane history separate, and not only contemplated recurrences of barbarism but described barbarian ages (and religious peoples) with suspicious relish. Furthermore, an important factor in his historical cycles was the antagonism between patricians and plebeians which monarchies were able to control only for limited periods—before and after barbarism: “For the plebeians, once they knew themselves to be of equal nature with the nobles, naturally will not submit to remaining their inferiors in civil rights; and they achieve equality either in free commonwealths or under monarchies” (The New Science, prg. 1087, translated by T.G. Bergin and M.H. Fisch). A very obliging fellow in his daily transactions, Vico was not equally accommodating when he took up the pen to write the Scienza Nuova.

Croce never denied the existence of mystery in human life and never closed his eyes to violence and barbarism. But he invariably refused to have mystery turned into religion and perhaps only toward the end of his life faced the recurrence of barbarism as a foreseeable possibility. In his Hegelian heyday when he wrote on Vico (1911) he believed in dialectical progress, in elites, and in civilized conversation with past ages from a well-chosen vantage point. Thus his answer to Vico was to deny the existence of historical cycles and of class struggle and to turn Vico’s interpretation of myth and language into a chapter of the history of aesthetics. If only Vico had realized that fantasy and logic, economic calculation and morality follow each other in circles within any human mind at any given moment!

Of course if Vico had recognized all that, he would have written the three original volumes of Croce’s Filosofia dello Spirito rather than the Scienza Nuova. But one of the most endearing traits of Croce was to believe that if only somebody else had taken the trouble of sorting out the four activities of the Spirit, Croce himself would have got on earlier with the real job, which was to read poetry and to write history.

In an acute paper at the American Vico Symposium of 1969 Hayden White was one of the first to see how embarrassing Vico had proved to Croce and to his faithful friend Nicolini. One must read the whole of the historical works of Croce and Nicolini to be aware of the extent to which they found Vico uncongenial, notwithstanding their devotion to him, a devotion inseparable from their attachment to the city in which they lived. But a summary, sensitive and well informed, of their attitude to Neapolitan society is provided in the recent book by Croce’s daughter Elena, La Patria Napoletana (Milano, Mondadori, 1974). There Vico is kept in his place—almost unheard—at the other end of the social scale. Quite a different family symbolizes the Neapolitan motherland throughout 150 years. This is the family of Gaetano Filangieri, a younger son of the Duke of Arianello who at the end of the eighteenth century was admired by the whole of enlightened Europe as a legislator and administrator.

II

But now we shall perhaps have the chance of seeing whether—and how—Vico can survive without (so at least I presume) the direct support of San Gennaro. An Institute for Vico Studies has been created in New York. Its first international conference in January 1976 collected a galaxy of Vico scholars from various countries and was supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Council of Learned Societies, and the Rockefeller Foundation. This is the culmination of the new Anglo-Saxon interest in Vico which the reliable translation of the Scienza Nuova by Thomas Bergin and Max Fisch (1948) both made possible and encouraged. The recent book by Leon Pompa, a lecturer in the University of Edinburgh and a contributor to the New York conference, is another sign.

Advertisement

Isaiah Berlin has contributed more than anybody else to this new popularity of Vico since his long essay on him appeared in the volume Arts and Ideas in Eighteenth Century Italy in 1960. Berlin was a consulting editor of the notable symposium on Vico published in 1969 by Giorgio Tagliacozzo, the present director of the Institute for Vico Studies, and wrote one of the best papers in it. Berlin was also a participant in and contributor to the 1976 conference.

Yet I am reluctant to associate Berlin too closely with the present Vico vogue. A distinction is perhaps indicated by the title (Vico and Herder) of the volume in which Berlin has republished new versions of his Vico essay of 1960 and of a shorter, but very substantial, paper on Herder originally published in 1965. Vico and Herder together are something different from Vico alone. It is one thing to see in Vico the inventor of a new way of philosophizing “which has re-emerged only in our century” (as the blurb of the 1969 Symposium claims); it is another thing to take him as the first in that line of thinkers on human societies in which Herder was the next (without really knowing about his predecessor). As Berlin of course recognizes, their thoughts became commonplace in many nineteenth-century intellectual circles—perhaps less so in the twentieth century.

Vico and Herder were the pioneers in the study of human imagination and myth-making. They looked at societies, not at individuals. Vico took Homer not as an individual poet, but as the expression of heroic Greece in its myth-making mood: this is what he called the “discovery of the true Homer.” Herder chose Biblical poetry as his test case. He interpreted it as the voice of the national soul of the Hebrews in their worship of God and in their struggles with very earthly foes. Both attributed to poetry, and more generally to language, an essential function in shaping the life of each ethnic group. Both appreciated spontaneity and growth in societies which clung to their ancestral environments. Both practiced a new type of historical research aimed at discovering those strata of human experience which are least controlled by reason and scholastic argument. Not surprisingly they found what they wanted either in very ancient civilizations or in rustic “unspoiled” modern surroundings. Thus they came to contribute powerfully to the study of heroic ages (a term dear to Vico) or to modern folk poetry (a term made fashionable by Herder).

By the nature of their approach to history both Vico and Herder were bound to emphasize development in societies. But in their actual description of it they sharply diverged. Vico proposed a scheme of corsi and ricorsi in which civilization and barbarism alternated: too much civilization, that is too much reason, inevitably produced a reaction, a return to uncontrolled imagination and passion, which are the substance of barbarism. Vico probably never made up his mind whether Christianity would prevent further returns of barbarism. The last pages of the Scienza Nuova in the 1744 version, which are dedicated to this subject, are among the most obscure and difficult of the book. They show how uncertain Vico must have been about the impact of Christianity on the course of profane history. Herder, who had more time and inclination to change his mind repeatedly, presented a variety of solutions unified by a preference for the organic scheme in which each civilization corresponds to a stage of individual human life from childhood to old age. But Herder too defended the right of each civilization to be itself—that is to live as it suited it best, with its own religion, language, art, and morality.

Berlin is profoundly sympathetic to this approach to past and present civilizations. He must have found in Vico and Herder a welcome alternative to that analytical philosophy—carefully eschewing any problem about poetry and myth, indeed about history in general—with which he grew up at Oxford. More specifically he must have found in Vico and Herder confirmation and support in his own lifelong fight for cultural pluralism and respect for minorities (including his own—should I say our own—the Jewish minority). In this sense this volume on Vico and Herder is clearly connected with his study of Moses Hess and with some parts of his Four Essays on Liberty.

“Pluralism,” wrote Berlin in one of those essays, “with the measure of ‘negative’ liberty that it entails, seems to me a truer and more humane ideal than the goals of those who seek in the great, disciplined, authoritarian structures the ideal of ‘positive’ self-mastery by classes or peoples or the whole of mankind.” Berlin is especially attracted by Vico and seems to have formed a bond of admiration and personal understanding with the man from Naples who in poverty and solitude created a new science—the science of what is most spontaneous and traditional in human societies.

Advertisement

But to me what Berlin has to say about the various aspects of the thought of Vico and Herder is not the most interesting part of his work. However skillful and eloquent the interpreter may be, there is not much chance of saying anything very new about such wellknown thinkers. It seems to me ironic that, having perceived so clearly the weakness of previous research on the sources of Vico’s thought (as exemplified by Professor Nicola Badaloni’s learned studies), Berlin should indulge in speculations about the influence of French Renaissance jurists on Vico. Being a trained lawyer, Vico unquestionably knew—and often quoted—his Cujas, Hotman, Brisson, and Godefroy, but he never shared their efforts to understand specific laws by referring them to specific events and was altogether unable to follow them in their exacting textual exegesis. They tried to distinguish between Roman and German Law. He rejected their claims (without much understanding them) in the memorable prg. 1075 of the 1744 Scienza Nuova:

For the erudite interpreters of Roman Law resolutely deny that these two barbarian types of ownership were recognized by Roman Law, being misled by the difference in names and failing to understand the identity of the institutions themselves.*

Vico was not interested in the differences between national laws, but in the transition from heroic wisdom to human jurisprudence and vice versa.

What seems to me the really interesting feature of this book is Berlin’s awareness that Vico and Herder introduced into European thought ambiguities and ambivalences which, being rooted in reality, are easier to recognize than to discard. The problem emerging from each page is: How are we going to avoid moral relativism if we accept with Vico and Herder that societies are at their best when they succeed in expressing themselves most individually in language, customs, institutions, and religion? Berlin formulates his problem most explicitly in the essay on Herder, which can be said to hinge on it. There are, however, several explicit indications also in his essay on Vico, for instance:

Right and wrong, property and justice, equality and liberty, the relations of master and servant, authority and punishment—these are evolving notions between each successive phase of which there will be a kind of family resemblance, as in a row of portraits of the ancestors of modern society, from which it is senseless to attempt, by subtracting all the differences, to discover a central nucleus—the original family as it were, and declare that this featureless entity is the eternal face of mankind. [p. 87]

Neither Vico nor Herder would have admitted to relativism. But if relativism was not intended, what right had the Greeks to be Greeks rather than reasonable men as the Enlightenment conceived reasonable men to be? Berlin very patiently analyzes the arguments of Vico and Herder to discover whether they presented a pluralistic image of human behavior without turning into moral relativists. He does that with sympathy and gentleness, but also with his typical ultimate firmness. If I understand him correctly, he has to admit defeat: there is no reconciliation in Vico and Herder between cultural pluralism and absolute values. What is worse, there is no hope—at least no immediate hope—of bargaining oneself out of the dilemma. If San Gennaro has to be left to the Neapolitans (and Confucius to the Chinese) human brotherhood must depend on something less (or more) than universal rules of behavior, universal faith, and universal knowledge—to which some people used to add even universal language, either mathematics or Esperanto.

I do not think (as Berlin seems to be inclined to admit) that we can save from relativism Vico’s famous principle that man is able to understand his own history in a very different way from that of understanding the physical world, because he makes history, but merely observes nature. As soon as one grants that each society has its own methods of understanding and evaluating human affairs, no generally valid knowledge of history is admissible. Even without this logical difficulty I would hardly find Vico’s evaluation of historical knowledge very convincing. We are all increasingly aware that man can control the physical world more easily than his own history. Faced by the claims of the unconscious, of biological determinism, and of economic materialism, historians are inclined nowadays to envy the physicists and chemists who can manipulate nature by experiment. It is by no means obvious (as Vico would like to have it) that my understanding of my own past is clearer or more direct than my understanding of the past of the solar system.

In any event, it seems to me that, if cultural pluralism is accepted, Berlin leaves us with an open question about the inevitability of moral relativism. He could hardly have done otherwise, unless he had turned his two essays into a theoretical disquisition on the way to reconcile national traditions with universal values.

III

There is, however, a difference between his essay on Vico and his essay on Herder which may at least help to indicate where a future discussion on the truth of Vico and Herder could start from the very premises laid down by Berlin. He presents his essay on Herder as an analysis of three rather precise notions which the German thinker introduced into European culture—the notions of Populism, Expressionism, and Pluralism. By populism Berlin means the cultural, rather than political, interpretation Herder gave to the fact of belonging to a specific nation: populism was different from, if not opposed to, nationalism. By expressionism Berlin means the emphasis on the self-expression of groups as such. And by pluralism he means the multiplicity and incommensurability of the values of different societies.

Now it is remarkable that Berlin does not put forward a similar set of notions for Vico. Though Vico produced theories about myth, language, poetry, symbols, and stages of human evolution which have received attention and approval in many quarters, he cannot be described as a philosopher who gave an ideology (as Herder did) to later generations. Herder had a direct influence on romanticism and nationalism which not even the most extravagant admirer of Vico could claim for him. A careful comparison of what E. Quinet owed to Herder with what J. Michelet really got out of his beloved Vico would, I believe, confirm the far greater contribution by Herder to the national consciousness of the nineteenth century.

This is perhaps hardly surprising. As I had opportunity to emphasize in previous papers on Vico (most recently in a review of Pompa’s book in The Times Literary Supplement, September 5, 1975), Vico was not even fighting his immediate contemporaries. He was trying to re-establish against Spinoza the separation between sacred and profane history, and was of course defending against Descartes the legitimacy of historical as opposed to mathematical knowledge. He was also undermining Grotius’s notion of natural law. If in dividing the spheres of the natural and of the supernatural, of the profane and of the sacred, he seemed to be passably oblivious of Redemption as such, we have to remember that he lived in a city where the miracles of the local saints were more effective witnesses to the truth of Revelation than the original act of Salvation.

Though Vico was susceptible to interpretation in a populist key, one cannot say that—at least in Italy, where his thought was really effective—he encouraged research in popular poetry or myths or national differences. Where Vico’s influence is clearly visible he mostly provides a vague religious and providentialistic meaning to history—a somewhat edulcorated alternative to Catholicism—or, in more recent times, a painless introduction to Marxism. One of the few exceptions has recently been illustrated by Franco Venturi in Rivista Storica Italiana 87, 1975, 770-784. Under the influence of the first Scienza Nuova of 1725 Lorenzo Boturini Benaduci worked in Mexico between 1736 and 1743 to learn local languages and to study ancient monuments and traditions. His expulsion from Mexico prevented the completion of the great historical work he had been preparing, but he managed to publish a summary of the Nueva historia general de la America Septentrional in Madrid in 1746. No other direct or indirect disciple of Vico, as far as I know, imitated Boturini. Vico did not persuade his followers, as Herder did, to learn difficult languages and to explore remote civilizations.

On any interpretation (I think Berlin would agree) Vico’s relativism was more homely and less radical than Herder’s. Vico reflected on Homer, on Roman and feudal law, and on Dante. Like many of his contemporaries he was fascinated by the yet undeciphered Egyptian hieroglyphs, but was unable to read any Oriental text. He conscientiously kept away from the Bible. Being aware that Spinoza had treated it as a purely human document, he was determined not to repeat what he considered an error. He refused to extend his notion of myth to the Biblical stories.

In short, classical and Christian Western Europe was still Vico’s world. It was no longer Herder’s world. Herder had discovered the poetry of the Ancient East either in the original or in translation; he was enchanted by what he believed to be the authentic bardic poetry of Ossian, and he felt deeply about his German ancestors. With Herder one is at times on the brink of racism, as R.G. Collingwood did not fail to remark in 1936 when he delivered his lectures on the Idea of History. Though Vico and Herder are separated by little more than a generation (Herder was born in 1744, the year Vico died), that generation had brought about a new learning and a new patriotism. As the new patriotism is well known, I want to focus attention on the new learning, which Berlin mentions only briefly.

Between Vico and Herder there was a revolution in historical research. Oriental languages were studied as never before, and the ancient sites of Persia and India began to be known. Religious and legal texts, the existence of which had hardly been realized, were made available in translation, and scholars began to explore in earnest the secular literatures of the same territories. Even in attitudes toward Greece there was a change: more knowledge of ancient sites and of modern dialects and customs. The Bible lost its isolation. The ancient poetry of the Hebrews was compared with the poetry of other ancient nations. Their prophets were set beside other religious masters such as Zoroaster. The comparison of Biblical with other Oriental institutions became frequent. Discovery and comparison gave new glamour to Arabia, Persia, and India, not to speak of China, while the claims of the Hebrews and early Christians to uniqueness began to be doubted. This was the revolution which either induced or confirmed in Herder the persuasion that God was saying different things to different peoples.

In 1753 Robert Lowth published the lectures on Hebrew poetry which he had delivered in Oxford in the previous ten years. They were the first analysis of Biblical poetry qua poetry:

Why should we heap praise on Homer, Pindar and Horace and pass over in silence Moses, David and Isaiah?… In them we can contemplate poetry in its earliest stage, not so much excogitated by man as fallen from heaven.

A few years later, in 1758, the great Hebrew scholar of Göttingen, David Michaelis, in republishing Lowth’s lectures with notes and additions, could reproach the English author for not having compared Hebrew with Arabic poetry and not having noticed that Moses in Numbers 21, 27 had inserted an Amorite (Michaelis says by mistake “a Moabite”) poem and therefore disproved by implication the divine origin of Hebrew poetry.

In 1754 Abraham-Hyacinthe Anquetil-Duperron—with two handkerchiefs and two shirts as luggage—enrolled in a regiment of the Compagnie des Indes in order to learn to read the sacred books of India and Persia (or rather of the Parsees). It is equally characteristic of the period that he was turned into the recipient of a stipend from the king of France even before he boarded the ship which took him to India. The result was the first translation of the Zend-Avesta in 1771.

What E. Quinet in 1841 was going to call the “Renaissance Orientale” had started. Anquetil saw the implications. In the preface to his great work he outlined the design of a new Academy, a “corps de Missionnaires Littéraires” who were to work in Africa, Asia, and America, learning languages, exploring and collecting texts. After twelve years in the field the Academicians were to return to Paris to publish what they had collected and to enjoy fame. Sir William Jones, who had published his treatise on Oriental poetry in French the year before (1770), put into practice some of Anquetil’s ideas in 1784, when he created the Bengal Asiatic Society. He mastered Sanskrit well enough to publish Kalidasa’s Sakuntala, which took Goethe by storm.

Hardly less influential were the travels of Carsten Niebuhr in Arabia and Persia which resulted in the classic Beschreibung von Arabien (1772). Niebuhr provided a background to Mohammed and, by his new description of Persepolis (which had already been visited by Jean Chardin and others), to Zoroaster. Together, Niebuhr and Anquetil posed the question, which has not been solved to everybody’s satisfaction even now, of the relation between Zoroaster and Achaemenid Persia.

The Oriental Renaissance was reinforced rather than contradicted by the contemporary fashion of looking for Greek landscape and monuments in Greece instead of admiring Roman copies in Italian museums. Winckelmann himself formulated the program of the new era of exploration in Greece, though he never saw either Sicily or the Aegean. The Antiquities of Athens by Stuart and Revett was published in 1762 under the patronage of the London Society of Dilettanti. Each traveler to Greece and the East (or for that matter to Celtic Scotland or to medieval Spain) was a refugee from the Paris Enlightenment.

Herder, though a not very adventurous and increasingly disenchanted traveler himself, can be said to have been present in spirit whenever a new archaeological or literary discovery was made. He liked drawings of ancient places and read in the original or in translation all that came on the market from Anquetil to Niebuhr, from Ossian to the Cid, which he imitated in a successful pastiche. Niebuhr stimulated him to an interpretation of the friezes of Persepolis based shakily on Persian literary tradition. I am not sure how much of Firdausi’s Book of Kings Herder knew. In the Persepolitanische Briefe he addressed a dozen German professors to ask for approval of his interpretation and finally turned to Zoroaster himself. (“Appear, Goldstar, legislator of Persia, philosopher, wise and glorious Zoroaster, appear.” He did not appear.) Niebuhr also inspired him to make a very suggestive comparison between the most famous of Jehuda Ha-Levi’s Songs of Sion, which he translated, and some Arab poetry about the ruins of Persepolis.

The Sacred Books, becoming available suddenly from the East in all their exotic beauty, were a pointer in the direction of pluralism and relativism. If for Vico the basic alternative had been between barbarism and civilization (each with its own attractions), Herder was presented with a variety of equally attractive civilizations: it became difficult to find barbarians to escape to.

IV

At this point it is almost irrelevant to distinguish between the different intellectual climates in which Vico and Herder lived and their different personal attitudes. Herder was much more committed to the relativity of values because he knew too many of them and was, psychologically, less prepared to choose among them. He was much more susceptible to poetical emotions and therefore much more subjective than Vico. He liked out-of-the-way pieces of evidence, to the point of being carried away by a forgery like Macpherson’s Ossian. Possibly he was also drawn to relativism by his virtual abandonment of any separation between sacred and profane history. This aspect of his personality would have to be discussed in much more detail. In some of his earlier papers Herder tended to treat the Bible, like Homer or Herodotus, as a purely human document. Later—even in his fine book on Hebrew poetry (1782-1783)—he no longer excluded Revelation altogether from his interpretation. But it was a Revelation which could hardly serve as a criterion for a choice between religious or moral codes: it was a Revelation mixed with Spinozism and therefore manifested in all the actions of mankind.

Furthermore, Herder was almost entirely devoid of that interest in the development of private property and other institutions which gave some direction and order to Vico’s speculations on history. Such interest constituted Vico’s first line of defense against the sort of relativism which makes it impossible to choose either in the past or in the present (and therefore in the future). N. Badaloni in one of his most recent utterances on Vico, which happens to discuss Berlin’s essay in its first version, contended that according to the Scienza Nuova man can know his own history only when he is capable of rationality and operates according to a just social order.

Badaloni implies that there are for Vico both social and intellectual conditions for true historical knowledge, but when these conditions are satisfied, knowledge is absolute. In Badaloni’s formulation (Introduction to Vico, Opere filosofiche, Sansoni, Florence 1971, p. XXIX) there is obviously too much of his own Marxism: Vico was thinking of a human history guided by Divine Providence. But it is correct that even in autobiographical terms Vico felt that only at a particular time and within a particular society had it been possible for him to discover the New Science. Providence linked true historical knowledge to certain conditions:

By this work, to the glory of the Catholic religion, the principles of all gentile wisdom human and divine have been discovered in this our age and in the bosom of the true Church, and Vico has thereby procured for our Italy the advantage of not envying Protestant Holland, England or Germany their three princes of this science. [The Autobiography, translated by M.H. Fisch and T.G. Bergin: the three princes are Grotius, Selden, and Pufendorf]

Our attention, however, should rather concentrate on what it would be proper to call the second line of Vico’s defense against subjectivity because it may turn out to be decisive and help to save Herder too. Vico alludes repeatedly to his project of a dictionary of the mental utterances common to all the nations and underlying their different languages: Berlin refers to it in another context (p. 48). The project, first formulated in the Scienza Nuova of 1725, was taken up again in the 1744 version and is explained in prg. 144-145 (Bergin and Fisch translation):

Thence issues the mental dictionary for assigning origins to all the divers articulated languages. It is by means of this dictionary that the ideal eternal history is conceived, which gives us the histories in time of all nations.

Vico claimed to have found a universally valid language underlying the individual languages. He recognized that a universal history—of whatever type—cannot be written without the conviction that different civilizations communicate with each other.

In Herder this conviction is less clearly stated. But when all has been said about language as the expression of national and tribal peculiarities, it remains true—and Herder recognizes this emphatically—that languages are translatable, that cultures borrow from each other through verbal communications, and that ultimately man is capable of universal understanding through language. Language—Herder presses on—is that “organ of understanding,” is “the treasure house of human thoughts.” Not by chance, it was in direct reference to Herder and his translations that Madame de Staël in De l’Allemagne praised the German language as uniquely suitable to render the “naïve expressions of the language of each country.”

Thus Vico and Herder bring us back to the basic question of language. What I see as the next step after Berlin’s essays is an attempt to assess the validity of the notions of Vico and Herder about language as a precondition for whatever validity one is inclined to attribute to their notions about history.

V

As I implied in my initial remarks, I do not see much future in the Italian Vico tradition, as it stands now. Whatever the merits of Vico’s original intuitions, they have not helped the Italians to build up a historical method or an interpretation of the past with distinctive features. If anything, Italian “Vichismo” was and is a compromise—with Catholicism in the past, with Marxism in the present.

Whether the independent approach to Vico which is now being elaborated in Anglo-Saxon countries will lead to something of lasting value, it is too early to say. A fashion is not necessarily a method or a principle of interpretation. We shall have to read the Acts of the 1976 Vico Congress when they are published. But the recent collective volume edited by G. Tagliacozzo and D.P. Verene which presents itself as a continuation of the International Symposium of 1969 (Giambattista Vico’s Science of Humanity, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976, 496 pp.) has a disturbing feature among its many merits. The majority of the contributors who are concerned with the vitality of Vico’s ideas compare him with one other thinker (respectively Kant, Dilthey, Wundt, Husserl, Wittgenstein, Piaget, etc.) and conclude that the two thinkers can supplement each other. The invariable success of such a formula should have been a warning.

There remains, however, the question which seems to be central to Berlin’s book and which I should have liked to see even more sharply pushed into prominence by him: the question whether the defense and glorification of the peculiarities of each and any civilization are intrinsically bound up with moral (perhaps even logical) relativism. If this question is given priority, Herder may seem to become more relevant than Vico, because Herder was exposed to a variety of cultural experiences which were unknown to Vico. On the other hand, by his approach to institutional problems, and especially to land ownership, and by his keen interest in a universal vocabulary of the mind, Vico offers means of resistance to a relativism which was to a large extent also his own. Before we celebrate the vitality of Vico and Herder let us be certain where they are leading us.

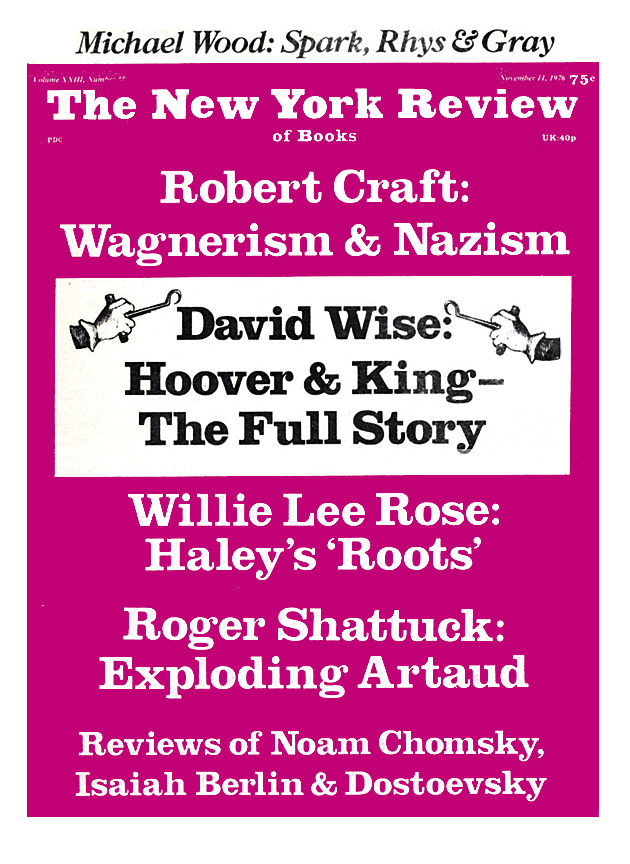

This Issue

November 11, 1976

-

*

Translated by T.G. Bergin and M.H. Fisch. ↩