One splendid evening last July I was sitting in a tourist-ridden outdoor café in Florence, talking with a friend about the recent Entebbe rescue. At the next table sat a wiry, middle-aged American woman nervously smoking Gitanes and nursing a bright red drink. Apologizing for having overheard our conversation, she asked if she could join us, pleading loneliness for the company of “literary New York Jewish intellectuals.” At once she began to talk about herself, in a random and defensive way, as if to assure us that her life had not been nearly so mismanaged as her worn features might imply, and her account had an unsuspected charm. (“I once had a mother-in-law, and her son, not the one that I knew….”)

But there were other things on her mind. She wanted to talk about Auschwitz. She remembered a review which Irving Howe had written of Lucy Dawidowicz’s book, The War Against the Jews, whose title just then eluded her—it was soon clear that what culture and opinions this woman possessed were derived from the pages of the Sunday New York Times Book Review. But she couldn’t recall a thing Howe had said. Had I seen it? And so began a rather macabre conversation.

I tried to change the subject; it wasn’t exactly my idea of a casual chat, and I had anyway come to Florence to consider Massaccio, not Maidanek. But she would not be deterred. Weren’t all those pictures of the concentration camps awful? How could it have happened, and what did it mean? I said that I wasn’t sure. Had six million Jews really perished in the camps? Only four million had, I replied, and the other two million in local massacres and from starvation. We ate sandwiches. Did I know any survivors? I did. How had they survived? I told her that that was a long story. But she wasn’t interested in a long story. She wanted to know if I had an answer and, in the same breath, if I had a match. She mumbled something about Seven Beauties and was silent. The waiter brought our check. Then she smiled, with that delusive look of achievement which comes over a face after an edifying therapy session. “I think it’s wonderful, you know,” she said. “Just wonderful.”

What was wonderful—so I presumed—was that even on a summer day in Italy, amid the frescoes and the Fiats, Jews could still come together to wrestle with the great tragedy of their people. Of course she was right. We had inherited the same problem. And it was surely a wonder—if that is the word—that the extermination of the Jews of Europe has not been forgotten, and is not likely to be.

Still I was disheartened. A pilgrim to Florence, she was no more than a tourist to Auschwitz. Her talk of it had been so convivial, so alarmingly free of struggle. She cared nothing for history. The camps were for her a means for organizing her own personality, a highly potent stimulant for Jewish identity. Her opinions, delivered over drinks like so many vers de société, were spoken with great satisfaction, even in tones of self-congratulation—how deep and how Jewish she held herself to be. As she prattled on about “the Holocaust” I realized that the expression itself had taken much of its sting out of her consciousness, and deceived her into believing she had some genuine grasp of the terror.

Not that I was surprised by her attitudes. Nor could I be offended by the personal fulfillment she gained from the catastrophe. She was after all in earnest about it, and exercised by it as best she knew how to be. For most people, perpetuating the memory of these murders has also meant that their responses to them have had to become routine; only a few have the powers of feeling and imagination that would enable them to escape such responses. Jewish tradition has always sought such a practical habituation to disaster. With ritual, custom, and myth the guardians of Judaism have effectively engraved the recollection of adversity upon the Jewish masses. And yet, for all the vulgarity that usually attends anything subscribed to by large numbers of people, I cannot believe that previous generations of Jews commemorated the annihilation of their forebears with quite the artlessness and lack of feeling with which many in our generation commemorate the Holocaust.

What of the “intellectuals,” from whom one might expect a more exigent appraisal of human action, a greater respect for history? Alas, no folk version of Auschwitz is as facile or mawkish or imprecise as some of the travesties currently being devised by our cultural betters. Consider, for example, certain critics of literature and film for whom any account of atrocity is just so much devotional reading. Some of them write as if they even wish they could have been there, in the midst of the cartage and the passion, and so could have acquired this century’s most terrible credentials. George Steiner, for example, candidly confesses to “a fearful envy, a dim resentment at not having been there, of having missed the rendezvous with hell.”

Advertisement

These professionals of suffering are not alone responsible for the sloppiness and sentimentality which now characterize discussion of the Holocaust. They find no shortage of books and films about which to write. Auschwitz bequeathed to all subsequent art perhaps the most arresting of all possible metaphors for extremity, but its availability has been abused. For many it was Sylvia Plath who broke the ice, her skin “bright as a Nazi lampshade,” her trials epitomized by “A cake of soap, / A wedding ring, / A gold filling.” In perhaps her most famous poem, “Daddy,” she was explicit:

I thought every German was you.

And the language obsceneAn engine, an engine

Chuffing me off like a Jew.

A Jew to Dachau, Auschwitz, Belsen.

I began to talk like a Jew.

I think I may well be a Jew.The snows of the Tyrol, the clear beer of Vienna

Are not very pure or true.

With my gypsy ancestress and my weird luck

And my Taroc pack and my Taroc pack

I may be a bit of a Jew.

There can be no disputing the genuineness of the pain here. But the Jews with whom she identifies were victims of something worse than “weird luck.” Whatever her German father did to her, it could not have been what the Germans did to the Jews. The metaphor is inappropriate. The images do not illuminate her experience, but only inundate it, and leave no statement but an inarticulate wail. Her unhappiness is made clear, but only by its need for poetic overstatement. The wildness and irresponsibility of the verse—constrained by its balladic rhythm—are what so move us.

I do not mean to lift the Holocaust out of reach of art. Adorno was wrong—poetry can be made after Auschwitz, and out of it. Witness Paul Celan, Amir Gilboa, and Jacob Glatstein, to name but three who did. But it cannot be done without hard work and rare resources of the spirit. Familiarity with the hellish subject must be earned, not presupposed. My own feeling is that Sylvia Plath did not earn it, that she did not respect the real incommensurability to her own experience of what took place in that darkness. Her many imitators certainly have not. They exploit the imagery of the Holocaust with no appreciable talent and in the service of a joie de mourir not very different in kind from that loathing of life which fills so much current pornography with Nazi paraphernalia and practices.

That trend which one irreverent critic has dubbed “death camp chic” continues unchecked. Elie Wiesel persists in converting his memories into religious kitsch and theodicy made easy. Terence DesPres’s harrowing evocation of the death camps has been widely praised, and blinds almost all to the foul final chapter of his book, one of the most uncomprehending studies I have ever read on the subject. The less said about Lina Wertmüller’s garbled film Seven Beauties the better. The Holocaust is too much with us. It has become an industry, a popular undergraduate field of study. So many words, so little instruction. Who can blame the American woman in Florence?

Apart from the insights of art, which cannot be prescribed, there remain at least two ways in which the question of the Holocaust can be addressed with dignity. The first is, quite simply, to study its history. The camps have by now become so shrouded in theology and legend that the sheer facts of what took place there must be made plain. This requires the sober, painstaking, unflinching attitude of the historian—Lucy Dawidowicz’s The War Against the Jews has set the standard—but that is not an attitude which need be confined to researchers and academics alone. Even in America, where myth has tended to get the better of history, it is not asking too much that people know more about the events over which they ceaselessly emote. Before facts so hideous, if they are really taken in, no tricks of the imagination, no indulgence of feeling, will go unchallenged.

The other way, still more bracing than the first, is to confront the Holocaust that lingers—to encounter the survivors. It is much easier to dodge the dead than the living, and hardest of all to dodge the living dead. Whatever else it was, the Holocaust was a punishment visited upon countless particular lives. It forever disrupted childhoods, educations, romances, marriages, families, habits, hobbies, careers, communities, traditions. It was primarily an experience of violent personal loss, the truest measures of which are the subsequent lives of its survivors.

Advertisement

Dorothy Rabinowitz’s tough-minded and tender book successfully recaptures this aspect of the tragedy; the survivors she writes about are far from the sociobiological problem-solvers of DesPres. Rabinowitz’s book centers on people, not theories. New Lives is a memorable gallery of portraits of refugees who came to the United States after the war and tried to begin again.

Between 1945 and 1951 roughly 92,000 Jewish survivors of Nazi Europe came to America; only Israel accepted more. These immigrants were a motley group: skilled and unskilled, educated and barely literate, rabbis, doctors, lawyers, tailors, artisans. Most were broken people, who came with nothing but sadness and anger. Few could speak English. Many, it turned out, were physically infirm. Most had relatives somewhere in America, saving remnants of old families which had been wiped out. They were ministered to by the combined efforts of the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, the United Service, and hundreds of local agencies of Jewish self-help. These obtained visas, provided temporary shelter, clothes, food, medical attention, a little money, and help in locating relatives, learning the language, and finding jobs. The refugees were dispersed across America, though a large number saw no reason to leave New York.

Rabinowitz’s book is about these fractured lives, about the mixture of resilience and tractability which saw many of these cowed people through the added shocks of relocating and into their new lives. The central feature of the histories of these people, needless to say, is their insurmountable thralldom to the past. They move in a universe of ghosts. In such a universe, too, were their children raised. I recall with horror a Sunday afternoon cookout in the garden—my parents, like many other refugees, accomplished much in America—when a cousin suddenly announced in an almost demonic whisper that the frankfurters cooking on the grill smelled to him like the burning flesh of thirty years ago. I remember my family’s weekly dread of “Dr. Kildare,” because Richard Chamberlain so closely resembled the murdered son of one of our relatives that she would break down at the sight of him. And a girl who grew up without dolls because her mother would faint in their presence: she had once been forced to wipe up the splattered remains of a Jewish baby that a Nazi had smashed against a wall.

Such are survivors’ days. Such, too, are the unremitting and almost imperceptible torments which Rabinowitz has vigilantly recorded. She is keenly alive to her subjects’ scars—to the nightmares that will not stop; the tranquilizers; the special sorrows of weddings and bar-mitzvahs; the dark-toned and tattered photographs of the dead, as precious as any relics ever were; the instability of the marriages rashly entered into after the liberation by frayed people bereft of bread or companionship; the accidental livelihoods that stifle talents; the craving for security and the certainty that there is no such thing.

It is no wonder that such men and women dreamed of nothing more fervently than of normality. Many were aware, however, that nothing was more forbidden to them. Succeed as they might, theirs could not be a common lot of mortgages and music lessons. Still, they could provide for themselves, and never again experience the helplessness of the war years. By the time they reached the United States they were adept at surviving. Rabinowitz diligently uncovers the mentality which sustained the refugees here. She sums it up nicely: “to be a survivor was to be removed for good from the possibilities of unworldliness.” Her subjects display a practiced austerity of personality. They are cautious and weigh things carefully—flamboyance and capriciousness were in most cases driven from their emotional repertoire. They are patient, practical, appreciative. They have learned to recognize opportunity, even to anticipate it. They are reticent and industrious, and most are wary of the limelight. They often live for their children.

The political dispositions of the survivors are accurate reflections of their experience. They had suffered persecution and found relief. Thus they opposed totalitarian abuses abroad and prejudice at home, but they could never believe the worst about America. They were proof that the United States was a very rare democracy—a trustworthy friend of Israel, another rare democracy—and they viewed with derision or irritation those in the late 1960s who saw America as a fascist state. Vietnam tested many. When the atrocities of Indochina began to appear on their TV screens, they could not avert their gaze, much as they might have wanted to. Even those who seemed to take no notice knew what was happening to those miserable, anonymous peasants.

While it could hardly be said that the holocaust experience had made the survivors more virtuous or humane than other men, and it was likely true that the darker capacities of some who had survived had been hardened and enlarged by their experience, still a great many of them were incapable of certain kinds of unconcern characteristic of other people: the ordinary man’s indifference to the tragedy of those far away, for example. They could never quite attain to the onlooker’s mentality, and they tended to respond viscerally to the most difficult of things to respond to: to tragedy in the mass—Biafra and Bangladesh, massacre and famine. It was not a choice of good over evil in the survivors that made them thus incapable of indifference; it was often not a choice at all, but a condition: whether they wished it or not, they would see what they might have wished not to see, and feel what it was most comfortable not to feel.

Rabinowitz perhaps minimizes the part that self-interest, and particularly Jewish self-interest, played in the political behavior of the survivors. But her description of their larger political sensitivities strikes me as otherwise correct. It was simply that their liberalism could never go against the grain of their own lives. They would not turn against America, however great their revulsion at its more odious policies. Vietnam they took to be a lamentable betrayal of America’s better self. Thus did a survivor of Belsen react to the massacre at My Lai: “How sad. How bitter that the sons of our liberators should now be the ones to do something like this.”

The survivors were imprisoned in their pain not least because nobody seemed able to understand it.

They soon learned that they might be asked, by friends and relatives, what it was like to starve, and after being told that starvation was very bad, the friends and relatives might respond that yes, they knew, because there had also been shortages of many things in America during the war, such as sugar.

Such benign incomprehension, however, was easy to cope with compared to hasty and heartless suspicions of another sort. Why, if so many perished so inescapably, had these survived? The question haunted survivors wherever they went; they could recognize it, too, in all the clever things psychologists had to tell them about their “guilt.” They were unprepared for the question, and were hurt by the implication that there was something squalid about how they won their lives. But they were not about to explain. They concluded instead that explanation was impossible, that for some purposes they had only each other. They became reluctant to talk freely about what happened, to open wounds before strangers. They were right. The degradations of the camps had made them into a new kind of human being. They were the mutants of modern history. And they had become not, as some in America have said, people twice-born, but, more precisely, people of whom their descendants would say with despair that they had been twice-dead.

In a hagiographical essay about Sylvia Plath, George Steiner wrote with his customary eloquence of “the capacity of poetry to give to reality the greater permanence of the imagined.” He was speaking of the Holocaust and “Daddy.” And he went on:

Perhaps it is only those who had no part in the events who can focus on them rationally and imaginatively; to those who experienced the thing, it has lost the hard edges of possibility, it has stepped outside the real.

That is the kind of writing that gives intellectuals a bad name. It is also one of the most mistaken and presumptuous sentences I have ever read in this connection. Perhaps there are not many survivors loitering in the common rooms of Cambridge and Geneva. But, barring a visit to Tel Aviv or New York, Steiner could, if he still believes what he wrote, do worse than have a look at New Lives.

Rabinowitz puts to rest that patronizing image of the survivors as a pitiable and inarticulate lot in need of spokesmen and writers and artists. The ordinary people she interviewed—a housewife, an importer of sewing machines, an insurance salesman—furnished her with accounts of their misfortunes as strong and convincing as, say, the very accomplished fiction of Jorge Semprun. They spoke with clarity and self-possession and even humor about the turbulence of their inner lives, about their Jewishness, about Eichmann and the Germans, about the need to remember and the difficulty of speaking.

What they did not share with her in any great detail is the world they had lost, and that is the only point at which Rabinowitz’s perceptions of the survivors differ significantly from my own. Those among whom I grew up never tired of recounting the joys and troubles of the vanished towns from which they came. They took special pleasure—and, I later realized, bore special pain—in regaling the children with luminous tales of the warm and elaborate festivities with which the Jewish calendar was marked in Eastern Europe. And, indeed, the religious manners of their new homes were never more than approximations, doomed to failure, of the religious manners of their old ones. No Passover seder when we did not hear of the epic seders of Poland, no Yom Kippur when we did not learn again of the saintly fervor of our grandparents. But such obsessive attempts to retrieve the past were not a monopoly of the religious, or would-be religious. Secularized Jews told proud and mournful tales of Vienna in its glory, of Kafka’s Prague. For all, these were the memories which measured the loss.

I have only a single and slightly unfair criticism of New Lives, and that is that it is finally insufficient for the study of its subject. It is a first-rate piece of dispassionate and humane reporting, but it is very short on analysis, on information, on social and historical background. Exactly how many refugees are there? Where do they live, and in what numbers? In what professions and classes are they to be found? How do they vote? How many are religious, and how many of these were religious before? What has been the fate of their children? New Lives does not give answers to these questions—nor did it set out to do so. But what Dorothy Rabinowitz intended she has achieved, and that is a much more trying task, one at which some of our best novelists have failed—the convincing re-creation of crippled human experience. She has found the fire in these exhausted lives.

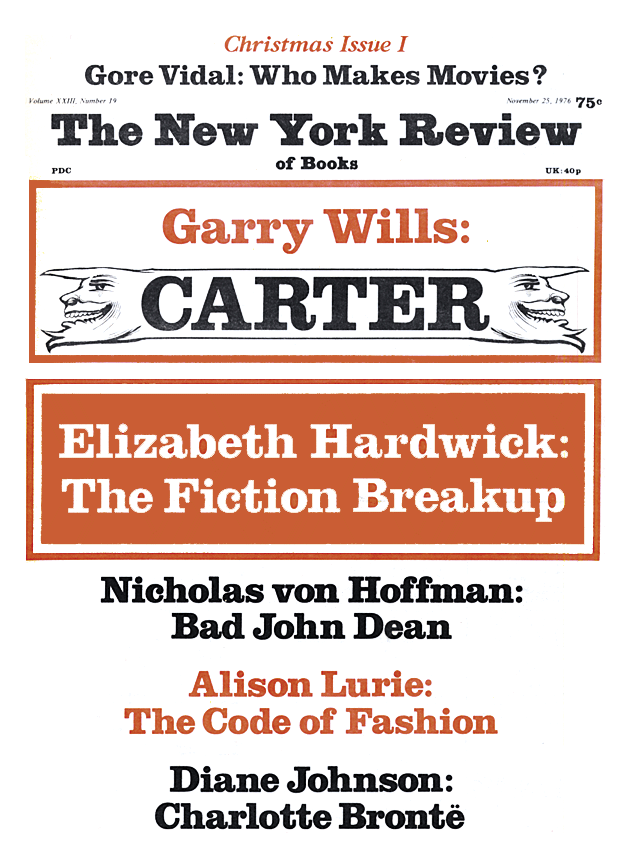

This Issue

November 25, 1976