Who needs an encyclopedia of over 3,000 pages, some 324 cubic inches (or about a fifth of a cubic foot) in volume, and containing more than six-and-a-half million words? The answer must be: everyone who is strong enough to lift it or to sustain its considerable weight on his lap without serious interference to the circulation of the blood. For everyone is from time to time in need of information not readily retrievable from the memories of his immediate domestic or social circle, the telephone book, or the dictionary. Such an aid to knowledge will be of the greatest value as long as that variety of human temperament persists which believes that questions of simple fact can be settled by pure, and usually noisy, argument. It serves, at the very least, as a practicing empiricist’s shelter from the fallout of misplaced reasoning.

The New Columbia Encyclopedia is the fourth edition of the traditional Columbia Encyclopedia, whose first edition came out in 1935 and which was substantially revised in 1950 and 1963. I have been a gratified user of the work since its second edition (my copy of which was made off with by an unworldly-seeming schoolmaster). The way in which the two succeeding editions have retained all the gratifying features of their predecessors, such as the inclusion of all Biblical proper names of persons and places, and the extremely helpful pronunciation guide, gives the special sort of pleasure provided by the survival, in a remodeled hotel, of a favorite bar. Of course, as my strength declines with age, the bulk of the work increases. With its 7,000 new entries bringing the total of entries to 50,000 it has increased by a sixth on that account alone. The new type used, a lucid but rather brutally unornamental lettering, suggestive of computers and prestige advertising, in place of the pleasantly old-fashioned, almost official-looking type of the past, appears to take up more space for a given amount of matter, thus bringing about a further enlargement.

Its greatest virtue is that it is still a one-volume work. That means that research can be carried on without moving from one’s chair; cross-references can be pursued, whimsical trains of free association can be indulged without having to exchange the volume in hand for another. What is more, the parts of the work remain in their correct or intended order. There is nothing to compare it with in English. The Micropedia part of the new Encyclopaedia Britannica, though it does have a lot of colored pictures, does not give all that much more in the way of essentials, and it takes ten volumes to do so.

Naturally nothing can be treated very fully in a work of this kind. The longest article, I think, is that on the United States, whose geography and history have to be covered in 13,000 words or so. It would be unreasonable to ask for more. What can be done to help the stimulated inquirer is to provide bibliographies, and these the editors have supplied, in the form of 40,000 references to further reading. On the whole they are well done and are commendably up-to-date. Thus four of the eight books recommended on the papacy were published less than ten years ago. This is an aspect of the work that could, however, be improved to valuable effect. To start with, on some important matters the reader is left without bibliographical guidance. Three recent books are cited on insanity or lunacy as a legal notion, but neither the article on psychosis nor the articles on schizophrenia, paranoia, and manic-depressive psychosis have any bibliography at all.

Secondly, there has long been a need, for I cannot be the only person who has felt it, for a reasonably thorough and authoritative reader’s guide, a list, if possible with comments on the main or most useful books, past and present, covering all the fields of human interest in the manner of a library catalogue, at appropriately varied levels of generality of classification. Such a thing would be tedious to compile, more tedious to keep up to date, would invite complaint from those left out or, as they judged, misdescribed, and might, quite justifiably, appear unprofitable to publishers. A bibliographically enriched version of this encyclopedia would, however, go a long way toward answering the need which it would serve. As the scope of knowledge expands and general education contracts the need increases continually. It is already recognized by those writers of textbooks and general surveys of some broad field of knowledge who put asterisks beside the bibliographically equipped items in their lists of further reading.

A fairly broad and variegated sampling of the contents has not turned up much in the way of absolutely straight-forward error. In one case of it the source of the mistake is identifiable. The article on the great Polish-American mathematical logician Alfred Tarski says, “His work is characterized by a basic acceptance and free use of the assumptions of set theory. For this reason he is regarded by some as a nominalist.” Sets are abstract entities. One who accepts and freely uses the assumptions of set theory would be regarded by some as committed to belief in the existence of abstract entities. Nominalism is the opposite of that belief. What has happened is that the concluding paragraph of the excellent article by Andrzej Mostowski on Tarski in the Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Paul Edwards, * has been carelessly transcribed. Mostowski says, “Tarski, in oral discussions, has often indicated his sympathies with nominalism…. However, the set-theoretical methods that form the basis of his logical and mathematical studies compel him constantly to use the abstract and general notions that a nominalist seeks to avoid.” In all fairness it should be said that at least the mistake quoted is a simple falsehood and so preferable to the pure gibberish of the entry on W.V. Quine in the Micropedia.

Advertisement

The concision imposed on the compilers of this encyclopedia makes heavy demands. These are often met, as in the entry on “fool,” which begins with the brisk explanatory formula: absurd person. But they are often conspicuously not met, notably in the description of such impalpable matters as the themes and distinguishing style of imaginative writers. The work of Grazia Deledda, we are told, “is lyric and in part naturalistic, and combines sympathy and humor with occasional touches of violence.” That makes her sound like Raymond Chandler. Only a very hard-hearted person could regard Evelyn Waugh’s Handful of Dust as “hilarious.” The novels of T.F. Powys are “original” all right, but they are not “realistic.” Banality, rather than error, is the prevailing fault here. The criticism of T.F. Powys’s most influential admirer, F.R. Leavis, does indeed combine “close textual analysis with moral principles of evaluation,” but that hardly catches the special flavor of his work, in particular the way the two things contribute to each other.

It is plainly very difficult to provide the nutshells of critical description that these examples try but fail to be. One brilliant exponent of the art, working in a neighboring field, is Leslie Halliwell, in whose incomparable Filmgoer’s Companion Kenneth More, for instance, is described as “British actor specialising in breezy roles.” Martin Seymour-Smith’s Guide to Modern World Literature shows that the thing can be done even in the more demanding realm of imaginative literature. In default of powers of miniaturization like these, a possible device would be to quote famous phrases preserved in dictionaries of quotations, like those of Bentley on Pope’s translation of Homer or Carlyle on Bolingbroke.

It is possible to regret one type of omission to the extent of being prepared to jettison the Biblical proper names in order to secure the space needed. That is of entries on fairly large, common-sensical “natural kinds,” areas of intelligent, if non-professional or non-scholarly, interest which have a history that would be worth assembling and a variation of forms that would be worth distinguishing. Consider the two most elemental of human pleasures. If you look up food you are simply referred, in a thoroughly depressing way, to frozen food, nutrition, and vitamin. There is no article on cookery or gastronomy, though there are biographical entries on Brillat-Savarin, Carême, and Fannie Farmer (but not on Mrs. Beeton). There are small, decent entries on “hotel” and “restaurant,” written from a somewhat commercial and pragmatic point of view and terminating, blithely, with references to motels and cafeterias.

If you look up sex you will find a general account of the biological phenomenon in general terms but human sexuality is covered only by scattered items on homosexuality and prostitution and fetishism. There is no entry on masturbation or, to move out further into the region of the disreputable, on torture, although sadism, as a psychiatric disorder, is included.

In general, omissions of general topics of this kind seem to be determined by the absence of a clearly institutionalized interest (scholarly or commercial) in the topic in question. That shows up in the frequent absence of one of an idiomatically associated pair. Thus matter is in, but not mind (parceled out, perhaps, between psychology and psychiatry); time is in but not space, universals are in but not particulars. However one common effect of overindulgence of the trade practices of scholarly contributors has been resisted. If you look up daisy you will find it and not a cross-reference to angiosperm, that dismal and oppressive terminus to which lines lead from all flowers and trees.

Most people educated enough to use an encyclopedia at all must be worried at times by their exceedingly feeble grasp of the latest developments in theoretical science. The article on quantum theory rises marvelously to the occasion. It is clearly and forcefully written, without hedging or condescension, enlivened with graphic explanations (“particles are found to exhibit certain wavelike properties when in motion and are no longer viewed as localized in a given region but rather as spread out to some degree”) and with possibly tricky terms defined. A neat history of the development of the original idea of the quantum of energy is appended. I know nothing so capable of producing a sense of understanding apart from a fine little book by Victor Weisskopf, which, apparently aimed at twelve-year-olds, struck me as just right for middle-aged adults. Relativity is harder, but the same merits are apparent in the article about it.

Advertisement

To go to the opposite extreme, from the contents of Nature to that of People magazine, there is no disdainful exclusion of the momentarily notable. This must have been a region of quite enjoyably agonizing editorial decision. Eddie Cantor and Elvis Presley are in; Danny Kaye and Doris Day are not. Paul Newman is present but Robert Redford and Jack Nicholson are not (let alone Robert de Niro). Bella Abzug gets quite a substantial article (ab’zoog), but Jimmy Carter appears only in the article on Georgia (“elected governor in 1970; his term was marred in part by conflicts with Lt. Gov. Lester Maddox…”). Jane Fonda and Vanessa and Lynn Redgrave edge in by way of inclusion in the articles on their respective fathers. Snoopy, in the article on Charles M. Schulz, is memorably described as “a romantic, self-deluded beagle.” Dwight Macdonald and Irving Howe make it, but not Philip Rahv. Oddly, more space is given to Brian Faulkner, the moderate, now discarded, Ulster politician, than to William Faulkner.

All in all, like the universe it so effectively describes, the New Columbia Encyclopedia, although clearly capable of improvement in various minor respects, is a proper object of gratitude and reverence and not just because each of them is the only one of their kind that we have got.

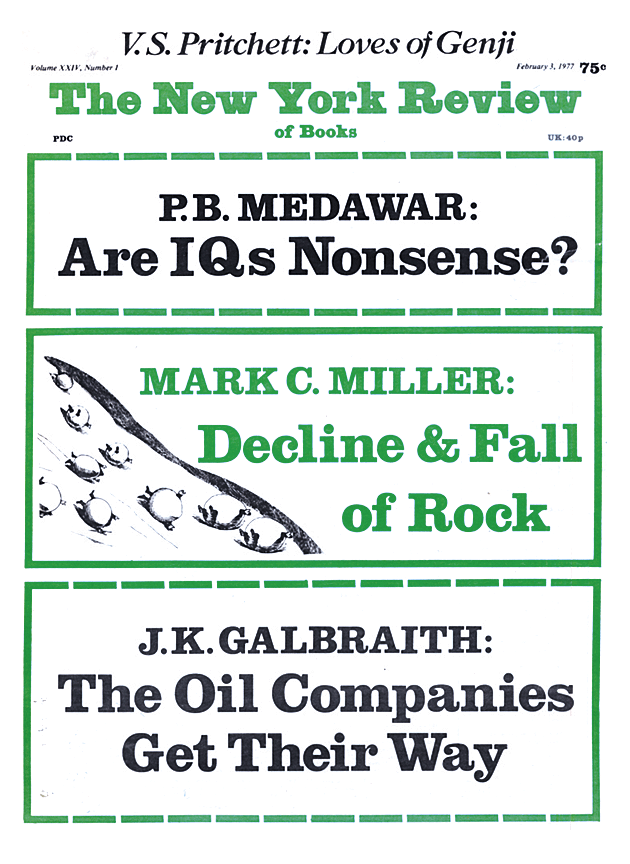

This Issue

February 3, 1977

-

*

Macmillan and the Free Press, 1967. ↩