In response to:

He'd Rather Have Rights from the May 26, 1977 issue

To the Editors:

In his excellent review (NYR, May 26) of Ronald Dworkin’s book, Taking Rights Seriously, Marshall Cohen identifies what he believes is one key to understanding Dworkin’s contribution in contemporary jurisprudence. “[Dworkin’s] attempt to ‘save the appearances’ and show that even in a hard case one of the parties has a legal right to win seems to me a major contribution to jurisprudence.” If we assume the great importance of Hart’s ideas in the present debate (as I think we can), and if we take Cohen’s lucid exposition of Dworkin’s work as accurate, then an understanding of the rightful basis upon which a judge may attempt to “save” appearances is of the utmost significance for the development of any just and coherent system of law. So far all seems clear, if difficult. Cohen, following in the venerable tradition of Anglo-American jurisprudence, seems to locate possible answers to this dilemma either in some kind of sophisticated utilitarianism, or in some new theory about individual rights against the government.

But nowhere does Cohen discuss the relevance of other traditions, or ways, of thinking about rights and about who ought to say what they are. Since Cohen says Dworkin’s book “should be read by anyone who cares about our public life,” and since Cohen is obviously a knowledgeable man, I believe he ought to.

For one, the significance of history for understanding the very existence of modern legal institutions (courts and judges for example)—among whose duties we find the application of principles where no rules for the determination of rights exist—is implied strongly by Cohen, but not discussed. “The origin of…principles lies not in the practical decision of some legislature or court but in a sense of appropriateness—often a sense of the moral appropriateness—developed in the legal profession and in the public during a considerable period of time.”

Although Cohen does not wish to go into this issue in his review, presumably because he is a philosopher and not an historian, I think on his own terms he cannot avoid it. It seems to me that, unlike most disputes among jurists and historians and sociologists of law, Cohen’s exposition leads, on its own terms, to legal dilemma that is sociological and historical in nature, not juridical. For, if recognition of legal rights in society depends upon some kind of social, in contrast to strictly legal, experience, why should we accept the authority of a profession of people trained in law as the arbitrator of our morals (why not a People’s Tribunal)? To Hart, of course, this historical and political dilemma is not legal in any sense of the term; for the existence of a constitution or of the will of the Queen in Parliament, as the supreme rule of legal recognition, is a political question, not a legal one. But it is, according to Cohen, to Dworkin. “In fact, no fundamental test of the kind positivists seek exists in the complex legal systems of countries like the United States and Great Britain. It follows that in these countries valid legal standards cannot be identified as those that pass such a test.” As a Talmudic jurist might say, Nu?

If Cohen is right about Dworkin, then I believe we have here nothing less than an internal critique of modern, western legal institutions. In trying to defend modern legal institutions, Dworkin may be raising the question of whether these institutions, rather than political parties, unions, the Church, or even popular revolutions (and so on), deserve the special place they occupy in our society. Once the authority to determine rights is extended beyond legislatures, why must that extension end with law schools, bar associations, courts, and so on? It simply will not do to propose that “the courts must frame and answer the questions of political morality that the logic of the constitutional text demands. There is no alternative if we are to take constitutional rights seriously.” Rights do not require constitutional form to be just. And the idea that all people are equal as a fundamental moral right is older than any modern legal system and more profound than any eludication to be found in jurisprudential thought. Why shouldn’t workers, the local PTA, rabbis and priests, ma and pa, and the revolutionary vanguard be included, in addition to or in place of the judges? The conception of rights bound up with the “general welfare” is tied historically to nation states. Once this connection is discredited, why must we continue to look toward the voice of that state—the legal profession—for an understanding of what human rights are all about? Other people take rights as seriously as good judges do; not the least of whom are people who challenge the belief that existing legal systems deserve unconditional faith.

Steven R. Cohen

New York City

Marshall Cohen replies:

It is neither Dworkin’s point, nor mine, that the legal profession, or that any other group, is peculiarly well placed to say what our human rights are. Judges do have a special role to play, however, in our legal institutions. Unlike industrial workers or officers of the local PTA they must decide cases that are properly before the courts. In order to determine the legal rights of the parties before them judges may, of course, need to investigate the moral and legal history of the community. (There is no “dilemma” here and certainly there is no reason why even barefoot philosophers should hesitate to observe that judges need to know history.) Then, too, as Dworkin indicates, when the legal rights of the parties turn on the interpretation of such terms as the Due Process and the Equal Protection clauses of the Constitution judges will only be able to determine what these legal rights are if they determine what moral rights these clauses seek to protect.

It is not Dworkin, but the legal positivist, who licenses the judge to act as a moral “arbitrator.” For it is the positivist, not Dworkin, who thinks that in hard cases the judge must “legislate” if he is to decide at all. Certainly, Dworkin says nothing to suggest that judges take moral rights more seriously, or understand them better, than discerning and conscientious workers, priests, or civil disobedients. What Dworkin does say is that unless judges attempt to understand what our moral rights are they will not be able to adjudicate under our laws. Judges are special in having assumed the obligation to do so. I believe that Dworkin has provided the best account of what that obligation amounts to.

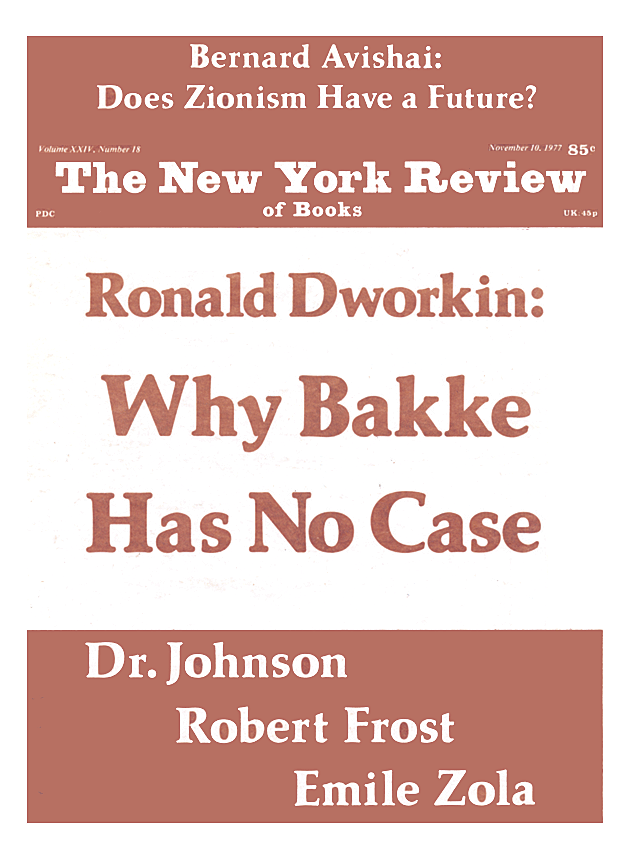

This Issue

November 10, 1977