To the Editors:

Perhaps you are already familiar with the name of Georgii N. Vladimov, a prominent Russian writer still living in the Soviet Union. On October 10, 1977 Vladimov resigned from the Writers’ Union of the USSR in protest over not being allowed to travel to the West to publicize his novella The Faithful Ruslan. In doing so he deprived himself of the possibility of making a living as a writer. Since his resignation, he has become chairman of the unofficial Moscow chapter of Amnesty International, a group which, as he says, “can get involved only in cases in other countries.” He explained his withdrawal and gave a vivid picture of what the Writers’ Union stands for in a letter addressed to its Executive Board. My translation of parts of this letter follows.

Nadja Jernakoff

Union College, Schenectady, New York

To the Executive Board of the Writers’ Union of the USSR

You did not let me go to the book fair in Frankfurt/Main where I had been invited by the Norwegian publishing house of Gyldendal. I have yet to spend a single day in the West, and will survive without these six; only, it is difficult to explain to the editor-in-chief, Mr. Gordon Hulmbach, who naïvely invited me, that my Union, a voluntary literary union of like-minded people, could conceal an invitation and not answer my inquiries, could prevent an author from meeting his publisher, his readers and his book. Will he understand, could it be translated for him if I should express myself in your frightful language of jailers and slave-traders: “ya nivyesdnoy“? [My status is that of a person forbidden to leave the country. Tr.]

It is even harder to admit to myself that I had illusions about your being able to understand another language, about the possibility of altering your nature. When my novella, The Faithful Ruslan, emerged and began to be dispersed in the West, you suddenly began to wonder about how much you really achieved with your constant pounding away at Three Minutes of Silence [Vladimov’s second novel. Tr.]—or was it simply that your hand had gotten tired? You considered my persecution, as well as my status of “undesirable,” which I always was for you, to have been a mistake, and you called on me “to return to Soviet literature.” Now I understand what price I had to pay for that return. This letter will be my last to you.

Did you realize where you were inviting me to “return”? To what forbidden little nook of caution and consideration? To that place where one must wait seven years for the publication of a book after it had been printed by the foremost journal in the country (the children born in that year have just entered school and have learned to read)? To that place where any semi-literate editor, even after approval had been granted, has the right to demand any cuts, even if they consist of half the text (this is not a joke—I have letters from M. Kolosoff)? And where ninety times out of a hundred (and if the work has been criticized in the press, then in all hundred cases) an independent court will take the side of the government publishing house and will uphold its decision that one must confine oneself within the “limits of the novella”? Those specialists in literature among you, for whom this terminology is unfamiliar, address yourselves to Judge Mogilnaya—she knows!

Ten years ago, in a letter to the IVth Congress [of the Writers’ Union], I spoke of the beginning of the Samizdat era—and now it is already coming to an end, and another, much lengthier one, is coming—the era of Tamizdat [publication “over there,” outside the Soviet Union. Tr.]. In reality, hated by you, Tamizdat always existed, like a flight deck in the ocean on which the tired pilot could bring down his plane when domestic airports refused to let him land.

Russia has always been the country of the reader—a reader who went through hell and high water. How they tried to pull the wool over his eyes—with official praise, with lists of Stalin Prize laureates sunk into the waters of oblivion, with decrees about ideological mistakes, with lectures by all of your secretaries, with all-Union anathemas, with the writings of “distinguished steel-workers”—and still they weren’t entirely successful. Russia’s best reading public, consisting of readers who knew the value of an honest, not a false book, stood its ground and crystallized. Besides his basic responsibility to simply read, this kind of reader took on another burden dictated by our time, the burden of safeguarding books from physical destruction; and the more zealous the attempt at elimination, the more jealously he stands guard over them. He stood guard over Esenin for thirty years until his works appeared in print again; he still guards the typewritten Gumivev; he already guards Ivan Denisovich and he took for safekeeping In the Trenches of Stalingrad, library stamp and all. Is that book overdue, is it stolen, did he have to beg to keep it? No matter; but he saved it from the knife of the guillotine.

All efforts to direct the literary process must be cast aside, just as you wittingly reject the schemes of an eternal power. Literature is above controls. But one can help a writer in his most difficult task, or hinder him. Our mighty Writers’ Union invariably prefers the latter since it has always been—and still remains—a political apparatus, towering high above the writers and voicing hoarse urgings and threats. If only it had stopped at that! I will not read out loud Stalin’s list—it is too long, more than 600 names. At the very outset, the Union—that most faithful companion of the evil will of the all-powerful—being most fervent in its initiative, put the stamp of legality on this business, and condemned these people to sufferings, death, and extinction during decades of detention. And still you will justify yourselves: those were the mistakes of a former leadership, you will say. But under what leadership—present, past or intermediate—was Pasternak “congratulated” for his Nobel Prize, was Brodsky exiled as a parasite, were Sinyavsky and Daniel thrown into camp barracks, was the three-time cursed Solzhenitsyn driven out? The ink had not yet dried on the Helsinki agreement when new punishments were meted out: the banishment of my colleagues, members of the international PEN club.

By persecuting and banishing everything that is rebellious, “mistaken,” contrary to socialist realist literature, indeed all which formed the power and prime of our literature, you have destroyed in your own Union any individual undertaking. Yet it does exist—whether in a person or in a group—and a small hope remains that there will be a turn toward repentance, toward renascence. But after the squandering of chessmen, the situation on the board has been greatly simplified: the pawns have it at the end, the dull ones lead and win. We have reached the limit of irreversibility, when writers whose books are neither sold nor read dictate to those whose books are sold and read. Your governing bodies, your secretariats, your commissions are flooded with this dismal mediocrity….

Remaining in this land, I, at the same time, do not wish to be with you. I exclude you from my life, not just in my name alone, but in the name of all those whom you have excluded, whom you have “officially” condemned to destruction and oblivion, and who, I believe, would not object, even though they did not empower me to speak for them. Of the tiny group of admirable, talented people, whose presence in your Union seems to me accidental and forced, I today ask forgiveness for my withdrawal. But tomorrow they too will understand that the bell tolls for each of us, and that each knell is deserved: each one of us was a persecutor when his comrade was being driven out. Even if we did not strike a blow, we supported you with our names, our prestige and our silent presence.

Carry on the burden of mediocrity, do what you are fit for and called upon to perform—crush, persecute, detain. But leave me out.

I am returning card No. 1471.

Georgii Vladimov

Moscow, October 10, 1977

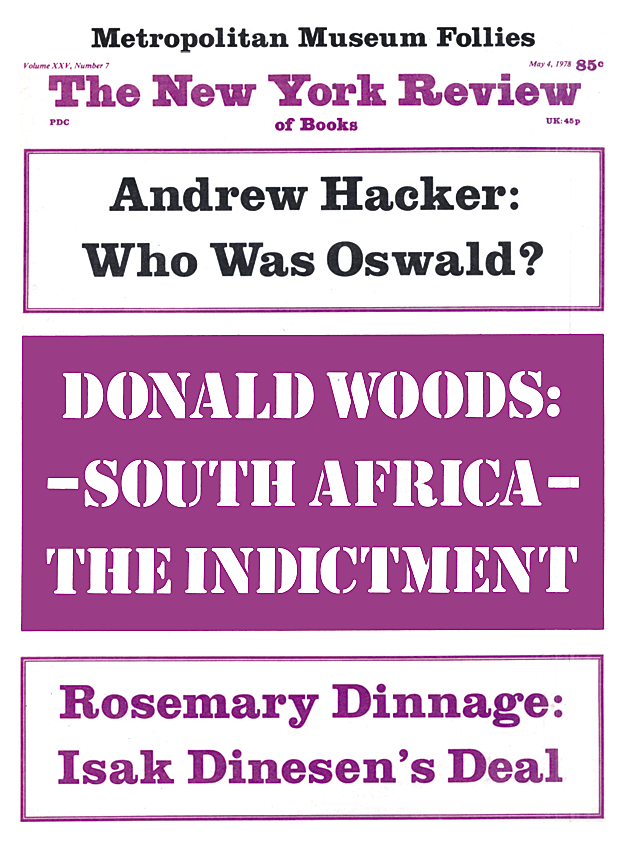

This Issue

May 4, 1978