His life is obsessional, far beyond that of most people or most writers. Everything is arranged in advance and happens on time. He is bothered by a pencil out of place in his study, looks for the known reflection of light in a particular place on a piece of furniture, and is disturbed if it has moved. And he withdraws from the outside world into his house and his family, just as within the house he withdraws into his study. His wife D, the three children living at home, what more does one want? The nurse, maids, secretaries in the house are necessary, but they are also an irritant if they intrude at the wrong times. The children are loved, but still he is disturbed “if they burst in when I’m alone with my wife,…for instance when we’re having coffee after lunch.” Food is taken at exact hours, give or take five minutes. D, his wife, has her occupations too, or perhaps they should be called her duties. “The least slip-up, the least whim, spoils everybody’s schedule.”

This obsessive need for organization extends to the work. The “Do Not Disturb” signs, the four dozen newly sharpened pencils, pad of yellowish paper, envelope giving the names, ages, and addresses of characters, these are all necessary preliminaries to beginning a book. Another disagreeable necessity is physical sickness, expressive of his deep anxiety about the work to be undertaken. Then eight or ten days of total absorption in the book until it is done. Or perhaps no luck. “A little shame, I admit, at D, the children, the staff, seeing me come out of my office before time.”

With the book finished, celebration. An urgent, and again obviously obsessional, need for sex. After completing one book he goes to a night club with D, and there takes the telephone numbers of four performers. The need for them is not emotional, but “a necessary hygienic measure” purging those “dreams and vague urges…which I believe poison most marriages.” Emotion is reserved for D, this routine sex is “a kind of inoculation.” It is indeed only a faint echo of the sexual activity of his youth when he was at times “like a dog in rut.” This need is, he thinks, perhaps not for the mere act of sex, it is part of a desire to “penetrate humanity….”

This account of Georges Simenon’s activities when he was still writing novels (he has now given up fiction, but dictates book after book of journals) comes from When I Was Old, the notebooks he kept between 1960 and 1962. He was nearing sixty, and suffering traumatic fears and doubts, which left him after this period. The novel Pedigree, written twenty years earlier, is generally taken to reflect the reality of Simenon’s early life, although he has said himself that it may be much too literary, and also that it is not really accurate. Pedigree is an essay in concealment rather than in revelation and is, perhaps for that reason, a dullish book.

When I Was Old, on the other hand, is disturbingly honest. Nobody reading these journals could doubt Simenon’s love for his wife and children, but who could be really happy living in that thirty-six-room château outside Lausanne, with every word and action fitted to Simenon’s needs? It is not surprising that for much of this time D is suffering from some mysterious mental illness. Simenon tries to help her, and notes with regret that what he does often has an opposite effect. “What did I say to provoke a painful crisis? I don’t know at all…. There she is, depressed, beaten, and anything I say hurts or wounds her.” He plays with his children, is fascinated by their development as individuals and has no desire to own them, yet it is inevitable that his activities should shape their lives.

Shape and, one must add, damage. Nearly a decade after keeping these journals, Simenon was living in relative isolation with his twelve-year-old son—plus, it is true, a staff of twelve including two private secretaries. D and an eighteen-year-old daughter were at this time both in a psychiatric hospital, and for almost a year Simenon was not allowed to see his daughter. During a remarkable TV interview in 1971 with a psychiatrist and a forensic pathologist, Simenon talked about these things and expressed his sorrow for what had happened without feeling any responsibility for it. He discussed himself impartially, playing the roles of both doctor and patient. At the end of the interview he took up a question by the pathologist about whether he liked Van Gogh, and answered it with his customary candor:

I see maybe they make a kind of comparison with him because Van Gogh was completely unconscious of what he was doing and it is the same with me, we are about the same. Maybe I am not completely crazy, but I am a psychopath, and they know it I am sure.

One cannot understand Simenon’s work without considering his personality. In one sense it is true to say that what we are is what we do, but in another sense what we are is what we desire, and often Simenon’s desires seem the opposite of what he has done. His life is full of self-imposed restrictions but what he wants, as he told the TV interviewers, is the total liberty of a man without possessions, typically a tramp sleeping under a bridge in Paris. Such a tramp would be a truly superior man. “It’s superiority not to need all those gadgets, a house, a woman, anything—you just sleep on the stones, eat some old bread with a piece of sausage and a bottle of wine—I consider that is superiority.” It is easy enough to point out that Simenon’s life in practical terms shows a passion for acquisition—of boats, houses, women—but his unique quality as a writer springs from the intensity with which he is able to imagine quite different existences.

Advertisement

He has said more than once that for the time he is working on a novel (which may be less than a week, and is rarely more than a month) he becomes the central character, so that it is not through his intelligence that this character goes down on the page, but by his instinctive understanding of what such a person would say and do. His hard novels—that is, those that do not concern Maigret—fall into two main groups. In the first a few characters are pressed into close contact with each other like people in a crowded train. The claustrophobic contact breeds conflict, and the conflict ends in violence. In the second group of stories there is a central figure who tries to fulfill that desire of Simenon’s to start out all over again, something expressed in his own life only by gestures like getting rid of all his furniture every time he moves. “To start one’s life over each time from scratch!”—that illusion of the tramp’s freedom is used in these fictions to generate stories of remarkable power.

A perfect example of this kind of story is The Man Who Watched the Trains Go By (L’homme qui regardait passer les trains of 1938), in which Kees Popinga, managing clerk to the leading ship’s chandler in Groningen, discovers suddenly that he is ruined. He realizes that the whole pattern of his life is a fraud, including the devotion he has given to the loving family by whom in fact he is bored. Inspired by the defalcating boss of his firm, who is about to stage a fake suicide and disappear, Popinga decides to start again from scratch, and in the course of doing so becomes a multiple murderer. He ends in a lunatic asylum, visited occasionally by his wife, who consults him just as in the old days about family matters. He starts to write an article headed. “The Truth About the Kees Popinga Case,” but gets no further than that heading. As he says to the doctor, “Really, there isn’t any truth about it, is there?” Popinga has no responsibility for the things that have happened, he is the victim-villain of his destiny. This theme is elaborated in many books—for instance in Monsieur Monde Vanishes (La Fuite de Monsieur Monde of 1946) and Act of Passion (Lettre à mon juge of 1947), in which a murderer writes a book-long letter to his judge before committing suicide, maintaining that “we are almost identical men.”

Three recently published books emphasize the other theme, of emotional claustrophobia. The Iron Staircase (L’escalier de fer of 1953) is about a husband who believes that his wife is poisoning him so that she can marry a lover, and faces the truth he has never admitted, that she poisoned her previous husband to marry him. He sets out to kill the lover, but ends by shooting himself. The Girl with a Squint (Marie qui louche) belongs to the same period. Two girls come to Paris from the provinces. Sexy, calculating Sylvie tries to use men to make a fortune, her friend the squinting Marie remains wretchedly poor. Sylvie uses her friend to destroy a will that would prevent her getting an inheritance, but finds herself linked indissolubly to the other woman afterward. In The Family Lie (Malempin of 1940), a doctor watching over his young son who is critically ill meditates on his own childhood and forces himself to admit and accept the fact that his parents murdered an uncle who was said at the time to have disappeared.

Advertisement

For Simenon close emotional contact almost always implies physical expression—the image of the crowded train with bodies rubbing against each other is a fitting one. The urgent sexuality of the wife in The Iron Staircase and of the narrator’s aunt in The Family Lie are potent elements in the crimes, and although the relationship of Sylvie and Marie is never physical, its sexual nature is made plain.

One is inclined to call these groups of books characteristic, yet nothing in Simenon can truly be called that because his range is so wide. Many stories exploit different themes—The Little Saint (Le Petit Saint of 1965) for instance, of which the author said that it expressed his basic optimism and pleasure in life, and that “if I were allowed to keep only one of all my novels, I would choose this one,” or the universally admired The Stain on the Snow (La Neige était sale of 1948). Yet even such books, which appear to be out of the main-stream of Simenon’s writing, suggest his deep interest in extremes of conduct. The little saint is a delicate freak, brought up in the violent world of working-class Paris before World War I. He accepts willingly all the insults and rebuffs showered on him, and fulfills his dream of becoming a successful painter. Frank, in The Stain on the Snow, becomes a pimp and murderer from disgust with his own background in prostitution and crime—nothing less than some equivalent extreme of conduct will do, and such a life is also perhaps his destiny.

Some generalizations can be made about these hundred-odd hard novels. Simenon is Belgian by birth but French in sympathies, and in its plotting his work belongs to a sensational French tradition that takes improbabilities for granted. In The Girl with a Squint the crucial event is Marie’s destruction of the will. How did she manage to steal this will, under the noses of the family intending to use it against Sylvie? Did the will exist at all? Because Simenon is interested only in the relationship between Sylvie and Marie, the questions are cursorily dimissed. Another book, The Hatter’s Phantoms of 1949, recently translated, asks us to accept the preposterous idea of a mass murderer who has killed his wife while maintaining the fiction that she is still alive, and so has to murder all the old school friends who are coming to see her on Christmas Eve.

If the plots are often incredible, we always believe in the characters. Simenon writes with the same Recording Angel’s understanding and impersonal sympathy about all sorts of professional men (especially doctors and lawyers), petty bourgeois shopkeepers, crooks, and workmen, less often and less well about the upper classes in society. The range of his women characters is equally wide, but he shows them less sympathy than the men. They are often destroyers (like Louise in The Iron Staircase or the delinquent who wrecks the life of a successful lawyer in In Case of Emergency), sometimes victims (like the girl suicide in Teddy Bear), or earth-mother figures like Gabrielle in The Little Saint.

The details of their lives are marvelously convincing. One of Simenon’s greatest gifts is for using the experience of his first forty years—childhood in Liège, early reporting jobs, and travels on his own account and for periodicals—and transposing it to different scenes and periods. The creation of the stationer’s shop in The Iron Staircase, with Louise down in the shop, Etienne in bed, and the iron staircase linking shop and bedroom, perfectly evokes an atmosphere in which Etienne is at the mercy of the poisoner. He seems all the more a victim because the fairground just opposite the bedroom window offers the promise of gaiety and freedom. The opening chapter of The Girl with a Squint conveys superbly the petty restrictions and sly sensualities of the provincial boarding house where Sylvie and Marie share a room and a bed. Simenon gives us the appearance and atmosphere of places better than most other living novelists. It is, very often, first of all through the places that we know his people.

To say this is not to endorse his admirer’s view that Simenon is a great novelist, let alone one with the amplitude of Balzac. His stories look inward, not outward. Where Balzac and Zola stretch out to comprehend their society, Simenon compresses society into the shapes of his obsessions. His stories gain something through the speed and intensity of their production, but there are losses too. The central character seems often not to be fully visualized, but to be a figure invented for the expression of problems occupying his creator. One remembers Simenon’s description of himself as a psychopath. When asked whether he cured himself through writing, he agreed that this was so.

His almost total lack of interest in history and politics limits the subject matter of the stories, and there are other limitations. “Suppress all the literature and it will work,” Colette told the young Simenon, and he took the advice very literally, trying “to simplify, to suppress, to make my style as neutral as possible.” Purple passages have been eliminated, but the result is not a prose that has the Orwellian clarity of a window pane. Simenon’s neutrality gives us a prose that has no vices, but few virtues. At times he offers us information with the blankness of a computer. The writer of the hard novels is the most extraordinary literary phenomenon of the century, but that is not the same thing as being a great novelist.

And so to Maigret. Not before time, it may be thought, but this relegation of the Maigret stories to a secondary position among his works would meet the author’s approval. Maigret is a kind of Old Man of the Sea that Simenon cannot shake off, as Conan Doyle was unable to get rid of Sherlock Holmes. The success of the Maigret stories compared with the hard novels can be summed up in the fact that almost all of the outstandingly successful Penguin Omnibus volumes contain two Maigrets and one hard novel. This does not please Simenon, and When I Was Old contains several slighting references to Maigret. He is “an accident to whom I attached little importance.” The books are “semipotboilers,” he wrote, and they compare with his “difficult books” as “light sex” compares to physical love with a beloved person. “There is no morality or immorality in Maigret,” he said to his TV interrogators with a trace of irritation. “He is a functionnaire who does what he has to do.” Yet Simenon himself has emphasized the similarity between the two kinds of books by introducing some characters—Lucas and Lognon are two—into both Maigret and hard novels.

The Maigrets recently published are certainly not very good. Simenon does not shine as a short-story writer, and Maigret’s Pipe is a distinctly inferior collection. The length at which the books are written is perfect for his gift of compressing into a novella material that most writers would put into a work of double the length. His short stories, by contrast, read rather like film outlines awaiting expansion. Maigret and the Hotel Majestic (Les Caves du Majestic of 1942) is a good deal better, particularly where it deals with the workings of the hotel, but if the Maigrets are minor Simenon, this is minor Maigret.

These books, however, are not typical of the Maigret canon. The Maigret tales have changed a good deal more than the hard novels over the years. Simenon is not in the ordinary sense of the words a detective story writer at all. He has no interest in the apparatus of clues, deductions, scientific examination of tire marks, or bloodstained hammers. Maigret, as he often says, has no method but operates by instinct. In the half dozen Maigrets that launched the chief inspector, as he then was, on the world in 1931, Simenon accepted the need to make some concessions to convention. An example is The Madman of Bergerac (Le Fou de Bergerac) of the following year, when Maigret knows that a murderer must have visited his hotel room because he has dropped a vital railway ticket in the passage outside the door. Several of the early Maigrets have sensational plots in the tradition of Gaboriau, du Boisgobey, and Gaston Leroux, and Maigret himself sometimes plays an active role for which he is really not suited.

After this flood of early books, Maigret was put into cold storage for several years. He emerged again in 1942 in more relaxed and coherent works, as the pipe-smoking philosopher interpreted by Jean Gabin and—of all unlikely figures—Charles Laughton in the films, and by Rupert Davies in the remarkably successful and sympathetic TV series. Maigret reached his peak during the late Forties and early Fifties. The later stories tend to find him drinking bars, considering Madame Maigret’s cassoulet, or philosophizing at the expense of the story.

If we say that the Maigret tales are second-class Simenon compared to the best of the hard novels, a qualification must be made: Maigret himself is the most fully realized character in the whole oeuvre. He has developed greatly, from the casually conceived figure equipped with appropriate detectival properties like his pipes and heavy overcoat to a man fully and lovingly known. He is based on Simenon’s beloved father, as the many overbearing, power-hungry women in the stories derive from his mother.

We know about Maigret in a factual way through Maigret’s Memoirs of 1950, which introduce an unusual element of humor in the young man’s courtship of Louise Léonard, but we also know his mind. Maigret is in many ways the ideal French bourgeois, although his father was bailiff at a château in the Auvergne, and even though he is called in one story a proletarian through and through. His love of food, drink, and comfort, the cushioned life provided for him at home by Madame Maigret, his lack of interest in politics, his commonsensible reactions to sex, poverty, crime—in all of these things Maigret is the average sensual man, gifted with an intuitive understanding of criminals’ feelings and attitudes that makes him an uncommon detective. It is an irony Simenon would appreciate that a writer so little interested in detective stories should have created the archetypal fictional detective of the twentieth century.

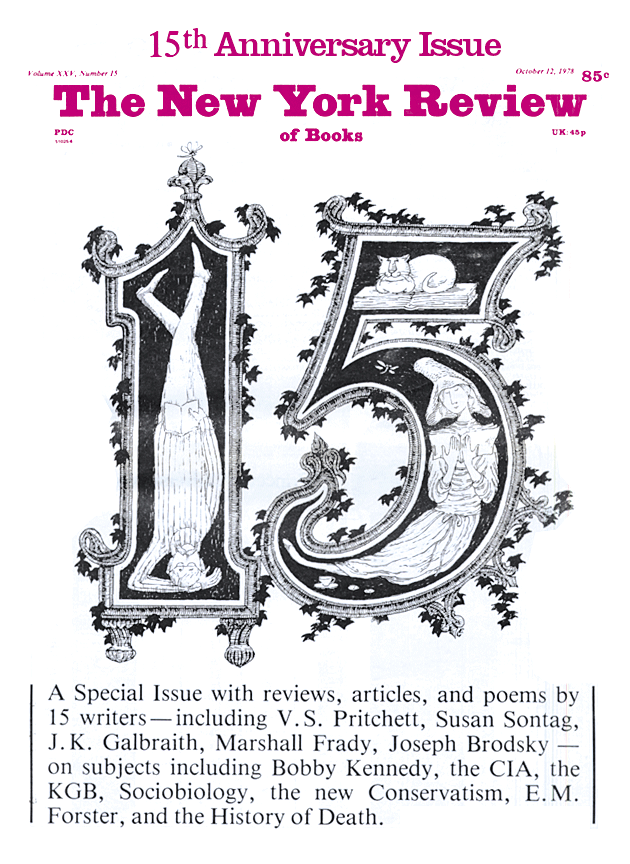

This Issue

October 12, 1978