In the years after World War I blacks began to migrate to the North and its imagined freedoms in great numbers—“Russian” came to mean a black who had rushed from the South. Along with them came the “Jazz Age” of the Charleston and the Black Bottom, of the musical hit Shuffle Along with Josephine Baker in the chorus, and of Scarlet Sister Mary with Ethel Barrymore in blackface. It was also the time of the “Harlem Renaissance” and the “New Negro,” when more books were published by blacks than ever before and more whites wrote about blacks than have ever done since. Langston Hughes wrote in his autobiography, The Big Sea: “I had a swell time while it lasted. But I thought it wouldn’t last long…. For how could a large and enthusiastic number of people be crazy about Negroes forever?”

Born in Eatonville, Florida, in 1901, Zora Neale Hurston arrived in New York in 1925 with, as she said, “the map of Dixie on her tongue” and $1.50 in her purse, one among many promising young black writers drawn to the Black Mecca. Eatonville was an all-black town, incorporated since 1886, self-governing, proud, not at all the “black backside” of a white city. No doubt this was a source of Hurston’s self-confidence and self-sufficiency, as well as the reason for her impatience with what she called “Negrotarians,” blacks who felt they had to launder their image in order to be accepted by white society. She herself was at ease on Park Avenue as well as on 137th Street, having been spared, in her all-black town, the sting of a childhood marked by daily encounters with racism. Hurston had no sympathy for blacks whom she felt were weak with self-pity and a sense of tragedy about their skin color. Throughout her life she tried to make literature out of the black folk culture into which she was born.

She had supported herself from the age of fourteen, working as a maid and a manicurist, and had already attended Howard University and won prizes for a short story and a play in a contest sponsored by Opportunity, an Urban League publication, when she arrived in New York. There she met other black writers and soon became known as the “Queen of the Niggerati.” Witty, intelligent, always “dressed down,” Hurston had only to open the door to make her presence felt. Her circle included nearly all the prominent black literary figures of the time as well as white writers like Carl Van Vechten and Sinclair Lewis. The frenzy of interest in blacks among whites also brought her introductions to upper-class white women like Katherine Biddle and Charlotte van der Veer Quick, who became her dictatorial patron. (She once received a list of expenses that included sixty-five cents for sanitary napkins).

While traveling with a “fast crowd” and developing as a writer, Hurston was admitted to Barnard College. The only Negro student enrolled in the school in 1925, she became what she called its “sacred black cow.” “If you had not had lunch with me,” she said, “you had not shot from taw.” She began to study anthropology with Ruth Benedict, becoming a dedicated student under Franz Boas.

Anthropology was, for her, a way of studying and preserving her origins. Hurston’s work has been generally neglected, another case of a black literary reputation not quite taking hold: those writers who do not fit the prevailing image of black history are discarded, left on the road like heavy baggage. Of her four novels, at least one is a work of stunning quality, and she was also a serious anthropologist. Robert Hemenway’s biography is invaluable in tracing Hurston’s development as a folklorist and the connection of her anthropological work to her fiction. Making extensive use of letters and manuscripts and long-out-of-print articles, Hemenway has for the first time painstakingly constructed the events of Hurston’s life. His biography also illustrates how difficult it is to place her in relation to her times, to describe her vehemence about the integrity of the folk experience.

The Harlem Renaissance was a period of contradictions, and the gaiety of the anecdotes that have come down to us veils its underlying seriousness. Hurston exhibited a strong inclination toward the iconoclastic, but the shifts in her opinions and the elusiveness of her personality sometimes make it hard to see her for what she was, a black woman ahead of her historical moment.

Hurston was never much concerned with respectability. She smoked Pall Malls on the street, told a blind man who once asked her for a donation that she needed the money that day more than he did, and took subway fare from his cup. (It is said that a man who made advances in an elevator was left face down when she got out.) During her early work in anthropology she went around Lenox Avenue with a pair of calipers, measuring the skulls of strangers. Langston Hughes wrote: “In her youth she was always getting scholarships and things from wealthy white people, some of whom paid her just to sit around and represent the Negro race for them, she did it in such a racy fashion.” And she never drank.

Advertisement

The character of “Sweetie May Carr” in Wallace Thurman’s novel about life in literary Harlem, Infants of the Spring (1932), is based on Hurston. Sweetie May enjoys playing up, with a great deal of tongue in cheek, to white notions about what a “darky” should be. “Being a Negro writer these days is a racket and I’m going to make the most of it while it lasts,” Sweetie May declares.

Hurston’s work, too, always stood apart from the aims and tendencies of the others in the Harlem Renaissance. The black writer Alain Locke did much to define one of the most influential of those tendencies when he published in 1925 The New Negro, a collection of writings heralding the spiritual emancipation of blacks, a sort of manifesto. Locke, along with W.E.B. Du Bois, believed that young black writers would speak for the inarticulate masses, serve as a guiding elite. Writers were to influence and direct the upsurge of the defiant will then in evidence among blacks. But Hurston refused to think of her portrayals of “the folk” as part of the tradition of protest demanding entry into white privileges. Assimilation, in her mind, meant diminishing the importance of black culture: blacks, for the sake of betterment, were, she felt, too inclined to flee the “frankly Negroid.” She insisted that fiction had an importance that transcended the race question.

Hurston wrote to Locke: “Don’t you think there ought to be a purely literary magazine in our group? The way I look at it, ‘The Crisis’ is the house organ of the NAACP and ‘Opportunity’ is the same to the Urban League. They are in literature on the side.” Of course the difficulty was that the constituents of the NAACP and the Urban League comprised the most accessible audience for young black writers like Hurston. Marcus Garvey, the Napoleonic founder of the Back to Africa Movement, whose following was largely among the deprived, was contemptuously regarded by the New Negroes, and this suggests the class character of the black arts movement.

In 1926 Hurston and some of her friends started an art magazine of their own. Fire!! was a self-conscious move toward the purely aesthetic, and the editors intended to publish material that would not fit into programs of racial uplift. It contains Hurston’s best story of the period, “Sweat,” about a washerwoman and her husband, his resentments and her will to survive. “Sweat” does not suffer from the awkwardness of Hurston’s earlier short stories, in which it seemed that her desire to celebrate the folk could not find its proper object. “Sweat” gives details of the daily drudgery, the isolation of a woman’s feelings, the limitations and consolations of lives formed by the folk ethos—and this was the substance of Hurston’s best work. Fire!! did not survive its first issue, and did not have the controversial effect its contributors sought. But it did give expression to the urge to break the solemnity of being a part of the “Talented Tenth,” to counter the idea that a black writer must represent his people.

Though Hemenway’s attempts to explain Hurston’s reconciliation of “high” and “low” culture in her sense of mission with the folk are somewhat cumbersome, he raises interesting questions about the inner pressures of her life and work. Hemenway sees Hurston as working in conscious opposition to what he terms the “excessively materialistic, hopelessly rational white society.” To see her as struggling against an oppressive, sterile, wasteful white society seems simplistic. She saw that freedom of the imagination was a kind of heresy against the almighty definition of blackness itself. The versions of black culture that were contrived for popular audiences enraged her. She considered her material stolen. The works of white authors like DuBose Heyward’s Porgy, Eugene O’Neill’s Emperor Jones, and Van Vechten’s best-selling Nigger Heaven she saw as obstacles to the discovery of the “real” thing, while serious black writers lacked a wide audience and had inner constraints to overcome. These “New Negroes” were often displayed but seldom heard.

Nancy Cunard, though, who was genuinely interested in Hurston’s work, is often dismissed as a mere pleasure seeker, her interest in blacks motivated by her hatred toward her mother and her love for the black composer Henry Crowder. A Harlem society column of the Twenties reports, “And yes, Lady Nancy Cunard was there all in black [she would] with twelve of her grand bracelets.” The sincerity of patrons and publishers was often doubted during the Harlem Renaissance. Rarely is there any mention of Cunard’s efforts to collect funds for and publicize in England the case of the Scottsboro defendants. With £1,500 she won in libel actions against four London newspapers that had sensationally covered her brief visit there with Crowder, Cunard was able to pay the printing costs of Negro, the large and ambitious anthology she edited, which was published in 1934. Negro printed contributions from William Carlos Williams, Langston Hughes, V.F. Calverton, Arna Bontemps, Ezra Pound, Du Bois, Josephine Herbst, Countee Cullen, Theodore Dreiser, Sterling Brown, William Plomer, Alain Locke, Louis Zukofsky, Jomo Kenyatta, Harold Acton, Hurston, and translations by Beckett. Sterling Brown, in 1942, was echoing a grievance first heard two decades before: “When we cease to be exotic, we do not sell well.” Negro was a flop. Perhaps a book on black culture that weighs eight pounds is doomed to failure.

Advertisement

Hurston’s essays in Negro—on the characteristics of black expression, the drama, the “will to adorn” in dress, in language; on the poetic quality of the black religious service—all stress the creativity and imagination indigenous to black culture. There is a great deal of humor in these essays and also a certain archness, especially when she draws a distinction between “genuine” spirituals and the “neo-spirituals” of the concert stage. “Glee clubs and concert singers put on their tuxedoes, bow prettily to the audience, get the pitch and burst into magnificent song—but not Negro song.” Or: “The idea that the whole body of spirituals are ‘sorrow songs’ is ridiculous.” Perhaps in her view of folk culture Hurston gave too much general significance to the Eatonville community.

Hurston traveled back to central Florida on a research fellowship from Columbia in 1927. “I want to collect like a new broom,” she wrote. Her first collecting expedition was unsatisfactory: when she said she was an anthropologist she found it difficult to gain the kind of acceptance that would have allowed her to hear the folk tales and work songs and observe the folk style. She returned to Florida in a glistening Chevrolet coupé, explaining she was a bootlegger’s woman on the run. This was more successful than presenting herself as an academic “poking and prying with a purpose” around the jook joints and turpentine camps and lumber jobs. She went on to New Orleans to collect conjure lore, where in order to be trusted by the hoodoo (or voodoo) practitioners she endured a bizarre ritual, lying nude for sixty-nine hours without water or food, a snake skin touching her navel. After the spirit accepted her, she drank blood mixed with wine. Hurston found voodoo to be a complex religion, one whose dignity she respected. The vividness of her descriptions of its practices seems to reflect her own private convictions about its powers.

Other collecting trips took her to the Bahamas and she went to Jamaica and Haiti on a Guggenheim fellowship. These expeditions resulted in two collections of folklore: Mules and Men (1935) and Tell My Horse (1938). Sorting out the material that became Mules and Men took her several years. Hurston was mainly interested in folk tales as communal tradition in which distinctive ways of behaving and coping with life were orally transmitted. She created for herself the voice of the self-effacing guide, wanting the material to speak for itself.

Describing the elaborate ceremony to “Make a Death,” in Mules and Men, Hurston ends:

The tongue [of a steer] was slit, the name of the victim inserted, the slit was closed with a pack of pins and buried in the tomb. “The black candles must burn for ninety days,” Pierre told me. “He cannot live. No one can stand that.”

Every night for ninety days Pierre slept in his holy place in a black draped coffin. And the man died.

Hurston’s book, economical in its scholarly apparatus, is still considered significant in refuting the “pathological” theories about black culture which held that what was distinct from white culture and behavior in the poor black culture was an aspect of deprivation. Previous anthropological research intended to prove that blacks were not inferior had undervalued the sophistication that Hurston found in the folk tales and jook songs and “lies.”

Mules and Men was criticized by blacks for its failure to illustrate deeply rooted resentments toward whites. Sterling Brown concluded that the book “should be more bitter; it would be nearer the truth.” But such criticism missed Hurston’s insights into the ways Southern blacks not only suffered from labor imposed on them by whites but, as Hemenway says, “cunningly escaped it.” Hurston retells a story of a master who “took a nigger deer huntin’ ” and then reproached him for failing to shoot.

Nigger says: “Well Ah sho’ ain’t seen none. Al Ah seen was a white man come along here wid a pack of chairs on his head and Ah tipped my hat to him and waited for de deer.”

This and similar tales, Hemenway feels, show how blacks escape punishment by retreating behind the clever mask of stupidity. The master here is being placed in a situation where his wishes have been thwarted, his appearance mocked, and, as Hemenway observes, “his own labor has been made as unrewarding as that of his slaves.”

Tell My Horse is a much more ambivalent and less concentrated study of Jamaica and Haiti. “The blacks keep on being black and reminding folk where mulattoes come from,” she wrote of the Jamaicans. She was annoyed with the mulattoes who spoke only of their white male parents and she privately called Jamaica an “island where roosters lay eggs.” She had a deep scorn for the pretensions of mixed blood. Hemenway finds her political analysis “naïve,” and no doubt some of her descriptions of Jamaica reflect American chauvinism and a lack of precision. In Haiti she had to cut short her research on voodoo when she fell violently ill, the result, she suspected, of local magic. “It seems,” she wrote to a friend, “that some of my destinations…have been whispered into ears that heard.”

Hurston’s novels were better suited to her gifts for dramatically representing folk life. Jonah’s Gourd Vine (1934) is an autobiographical novel about her parents, the philandering husband and suffering wife—fecklessness and rage arriving with the morning meals. Hurston had once written on the lack of privacy in rural communities such as Eatonville and she uses the townspeople not just as scenery but as a chorus, commenting on and adding details to the conflict between the main characters in carefully rendered black speech.

Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937) is Hurston’s most perfectly realized work. Janie Crawford, the heroine, is subversive in a way that was new in black writing. She is not the ruined or exceptional black woman full of insolence toward convention. She endures two long marriages and when she finds “true love” with a younger man in her widowhood her freedom is the sort that comes from being childless and well-off. Her grandmother had hoped to spare her the destiny of black women as she understood it from a life of slavery. “De Nigger woman is de mule uh de world as fur as Ah can see. Ah been prayin’ fuh it tuh be different wid yuh.” Richard Wright, then a member of the Communist Party, attacked Hurston for the “minstrel” image of blacks he felt she was perpetuating. This is a novel entirely outside the tradition of protest and its concentration on domestic life was probably seen by some black writers as too narrow to confront racist society. But Hurston’s book, written in seven weeks, gives not only her fullest description of the mores in Eatonville but also a lyrical and terse psychological portrait of a woman. Wright did not appreciate her lack of sentimentality about conjugal brutality or about the limitations of her folk characters, nor did he recognize that her ear for the vernacular of folk speech is impeccable.

Two aspects of Hurston’s life accentuate the problems of the career woman: marriage and money. A woman of Hurston’s temperament is bound to be ambivalent about domesticity. Ambition, for her, was an affliction. She makes it clear in her autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road (1942), that her career was a major obstacle to permanent attachments. But the autobiography is peculiarly reticent. From Hemenway we learn that Hurston was first married in 1927, separated four months later, and finally divorced in 1931. She married again in 1939 and filed for a divorce a year later. This husband, fifteen years her junior, claimed he was in fear of his life because of the professed voodoo power of the plaintiff to “fix him.” The divorce became final in 1945. Between marriages Hurston admits to one “parachute jump” into love. This man too was younger and the affair was protracted, stormy. He could not abide her compulsion for professional activity. “There must be a something about me that looks sort of couchy,” she said. One wishes to know more, but Hurston was obsessively secretive.

The Depression brought an end to Hurston’s private patronage. Her search for employment once led her to contemplate becoming a “chicken specialist” for the carriage trade. Though her books were well received she never made much money from them. Hurston was in any case notoriously bad with money. Advances evaporated. She worked in various capacities for the WPA, wrote sketches for the stage, had dispiriting experiences in the drama departments of black colleges (which she called “begging joints”), and was mostly preoccupied with bringing authentic folklore to wide theatrical audiences. In 1934 Hurston returned to Columbia as a doctoral candidate, but she had long wearied of academic discipline.

On September 13, 1948, the New York police appeared at her door on West 112th Street and arrested Hurston on the charge of having committed an immoral act with a ten-year-old boy. Her protests and denials went unheard. An employee of the court sold the story to the black newspapers—children’s cases were private—and the lurid publicity plunged her into fury and despair. She was indicted solely on the child’s testimony. The case was not dismissed until a year later—and only after her attorney had gone privately to the prosecutor with her passport proving she had been away during the time in question and after he presented evidence of the boy’s mental instability. Hurston was devastated. She returned to Florida, her back turned on New York and the early promises of the Renaissance, writing to Van Vechten, “I care for nothing anymore.”

In 1950 while waiting for a boat to sail to Honduras, and in desperate need of money, as usual, she accepted a job as a maid in a fashionable Miami suburb. A local newspaper reported the story of her dusting the library shelves while her employer sat reading a magazine—only to discover an article written by her “girl.” The wire services picked up the story and Hurston, intensely proud, explained that she was just taking a break from writing and gaining experience to begin a magazine for domestics.

But as resilient as Hurston tried to be, these scandals weakened her will. In the Fifties she wrote articles characterized by views that became increasingly paranoid, conservative, and inflexible. She supported Taft in 1952 and questioned the Supreme Court’s desegregation decision of 1954 because it implied, to her mind, that blacks could not learn unless they sat next to whites.

Hemenway writes:

She was never again so belligerently independent as she had been earlier. It is also true that for the last decade of her life she was frequently without money, sometimes pawning her typewriter to buy groceries, and that after 1957 she survived on unemployment benefits, substitute teaching, and welfare assistance. In her very last days Zora lived a difficult life—alone, proud, ill, obsessed with a final book she could not complete [a life of Herod the Great].

She suffered a stroke and, unable to take care of herself, was moved to a welfare home where she died three months later, in January of 1960. She was buried in an unmarked grave. “I have been in sorrow’s kitchen,” she wrote, “and licked all its pots.” Yet she challenged conventional plots for both women and blacks, with anarchic brilliance.

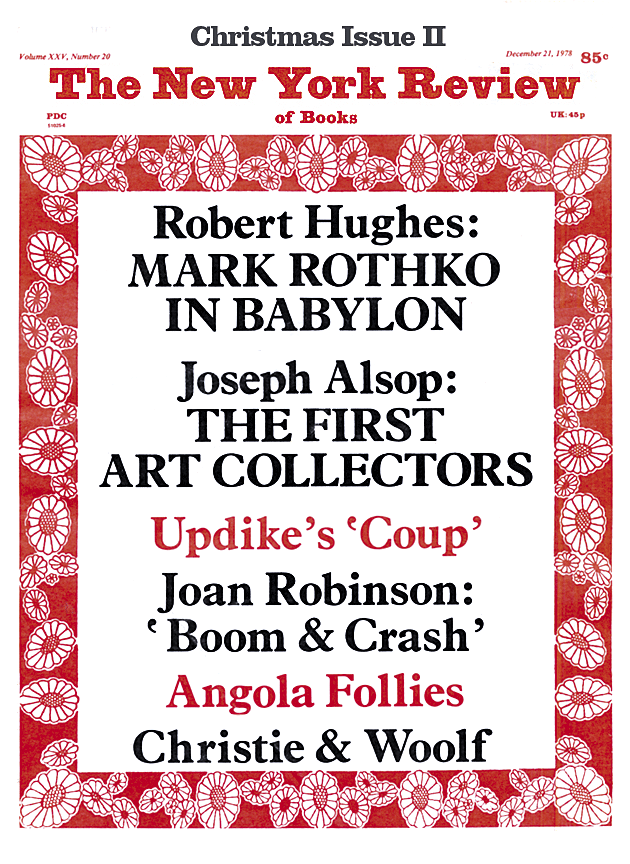

This Issue

December 21, 1978