First, the life.

Agatha Mary Clarissa Miller was born in 1891, the third child of an idle well-to-do American father, and a mother who was markedly sensitive and aesthetically perceptive. Her upbringing was unusual only in the fact that she never went to school, but instead was taught at home by her mother and a succession of governesses. Not, of course, by Mr. Miller, who lived like a super-typical leisured gentleman of the time. He left their house in the seaside resort of Torquay every morning, went to his club, was brought back in a cab for lunch, returned to the club for whist in the afternoon, and was home again to dress for dinner.

Such a way of things seemed natural to Agatha, who said afterward that her parents’ was one of the four completely successful marriages she had known. She was eleven years old when Fred Miller died after a series of heart attacks. Most of his money had vanished in ways that he never fully understood, but he survived to the end without having to do a stroke of work. Agatha considered him a totally agreeable man, and he provided a model for the many similar figures in her books. Another model must have been her much-loved brother Monty “Puffing Billy” Miller, who said to his sister once that he owed lots of money to people all over the world and had led “rather a wicked life…but, my word, kid, I’ve enjoyed myself.”

But Agatha’s mother Clara was the formative influence on the girl who never had any formal lessons. She must have been, by her daughter’s account, a remarkable woman, almost clairvoyant at times, fascinated by things mysterious and strange, a woman who saw life and people in colors “always slightly at variance with reality,” as Agatha put it in her autobiography. These qualities were passed on to the child, who evolved elaborate games which she played alone, observed the adults who were her chief companions, and accepted a code of manners and morals that stayed with her for life. Servants worked incredibly hard, but then of course they really liked it. They were professionals, and were to be treated always with the utmost courtesy. It was natural to be a true blue Conservative, a believer in the supremacy and benevolence of the British Empire, because although people with other opinions were known to exist, one never met them.

Certainly they were not to be found at the dances where Agatha always had a feminine companion, because “you did not go to a dance alone with a young man.” The girl who in 1914 married dashing Archie Christie was exceptionally innocent and naïve, and remained so all her life. She adored Archie, who became one of the first pilots in the Royal Flying Corps when World War I began, but it is doubtful if she ever understood him. Trains and houses were, as she mentions casually in her autobiography, always more real to her than people, and she was horrified and astonished when in 1932 an otherwise amiable German said that all his country’s Jews must be exterminated. Could such things be? Apparently they could, but she never cared to write about them.

Her marriage to Archie Christie was effectively ended when, after twelve years, he told her that he was in love with another woman. There followed the single public event in the life of this notably private woman. She left home, abandoned her car, and disappeared. The police treated the case as one in which her violent death could not be ruled out, but after nine days she was found living in a hotel in the spa resort of Harrogate, using the name of her husband’s mistress. There were immediate suggestions that the disappearance was a publicity stunt, and that her explanation of amnesia was inadequate. The facts point the other way. She was under immense stress at the time (her mother had just died, and Archie had told her that he wanted to marry his mistress), and she had no need of the publicity—in fact, her sales declined after the affair. The idea of a publicity stunt must also seem preposterous to anybody who knew her.

“Life in England was unbearable,” she said afterward, and she left the country, traveled a good deal, divorced Archie after holding out for a year in the hope that he would change his mind and return to her, married the archaeologist Max Mallowan, and became more and more successful as the years passed. “From that time, I suppose, dates my revulsion against the Press, my dislike of journalists and of crowds.” She became morbidly sensitive to any mention of the disappearance, and her natural shyness was accentuated to a point at which she refused to make any public appearance which would involve speaking even a few words. When she died in January 1976 she was certainly the most famous detective story writer in the world.

Advertisement

Kathleen Tynan’s Agatha is a “novel of mystery” about the disappearance. It is a complementary work to the forthcoming film with Vanessa Redgrave as Agatha, and reads very much like the book of the film script. The book is a contemptible production, ill-written, utterly vulgar in conception and execution, and a work that must cause extreme distress to Agatha Christie’s family, who have unsuccessfully opposed both book and film.

According to her publishers, Kathleen Tynan “became fascinated by the story several years ago” and now “poses an ingenious imaginary solution to an authentic mystery.” Her solution suggests that Agatha knew what she was doing all the time, and that it was her intention to commit suicide. She goes to Harrogate because her husband’s mistress Nancy Neele is there, and conceives a plan for her electrocution at Nancy’s hands, by inducing Nancy to turn on the current of a treatment called the Galvanic Bath. Nancy obligingly, and innocently, turns the switch, but Agatha is saved at the last moment by an admiring journalist who is half in love with her. “Suicide’s one thing, but to pin a murder on your husband’s mistress…” he says reprovingly. Agatha denies this, but it is not easy to see just what her intention was, except that she says she wanted to get Nancy in her sights. “I used to do that with the leopards when we went on safari.” In fact she never went on safari with Archie Christie.

The characterization is on the same plane as the rest of the book. Agatha uses phrases like “I think we’ll give it a miss” and “Have you noticed that a woman, if she’s naked, walks on tip-toe?” which are both out of period and out of character. The other figures are mere shades, from Archie, “a handsome man of thirty-seven” who won “countless medals in the War” (in fact three), to the extraordinarily dull journalists. It takes some exceptional quality to make journalists dull, but Kathleen Tynan has it. The story is a piece of total nonsense, but it may be taken seriously by readers and filmgoers who will feel that the author can hardly have made it all up. Altogether, this is the kind of book of which we can hardly have too few. One is more than enough.

And then the detective stories.

During World War I Agatha Christie worked in a hospital, and eventually found herself an assistant in the dispensary. There she conceived the idea of writing a detective story. Since she was surrounded by poisons, what more natural than that this should be a poisoning case? What kind of plot? “The whole point of a good detective story was that it must be somebody obvious but at the same time, for some reason, you would then find that it was not obvious, that he could not possibly have done it.” That is just what happens in The Mysterious Affair at Styles. And the detective? She was devoted to Sherlock Holmes, but recognized that she must produce a character outside the Holmes pattern. She rejected the kind of detectives flourishing at the time, like the super-scientific Doctor Thorndyke and the blind Max Carrados, whose sense of smell was so strongly developed that he could discern the spirit gum in a false mustache across a room, feeling rightly that these were not her kind of people. Her man was meticulous, neat, and orderly, faintly absurd. He was small, so she named him Hercules. His nationality was derived from a colony of Belgian refugees near her home. Somewhere the name Poirot appeared, the “s” vanished from Hercules, and—although he had to wait five years before he got into print—a Great Detective was born.

The people in Agatha Christie’s books look back, more than those of any other modern writer, to the world of her childhood and adolescence, that time when social life was settled and people knew their places in it. Her love for Ashfield, the sizable villa in Torquay where she grew up, is responsible for the many country houses in her books. She reflected late in her life that one of the things she would miss most, if she were a modern child, would be the absence of servants, and there are dozens of servants in her stories, butlers and housekeepers, housemaids and under-housemaids, gardeners and odd-job men. There were servants in only moderately comfortable households in England up to 1939 and World War II, but not on the Christie scale. She was looking back always to a style of behavior that had ended in 1914.

Advertisement

Her characters adjust to the clothes, and more or less to the speech of the time in which the books are set, but not to the occupations and behavior. Old buffers retired from the Indian Army or Civil Service linger on after their time, and there is a sharp division between gentlemen occupied in the professions and tradesmen, with doctors and dentists somewhere in between. There must be very few cases of tradesmen proving to be guilty parties in Christie novels (I cannot think of one), although of course the case would have been different if they were gentlemen in disguise. Servants almost vanish, naturally enough, in books set in the 1950s and 1960s, but still no Christie male ever has to light a fire or do the washing up. Women may be employed as secretaries or typists, but they are rarely seen working.

All this is not said in denigration, but to emphasize how totally the novels are set in a fairy tale world, the world that a critic has wittily named Mayhem Parva. It is one that perfectly fits the artificiality of her wonderful plots. The plots also can be traced to her childhood, to the endless stories that the happy but lonely child told herself about imaginary kittens who were also human beings, and her invention of three railway systems in the garden, with the stations marked out on a sheet of cardboard. Behind the middle-class English lady, remote and shy, whose perfectly appropriate occupation seemed to be the pouring of tea from a silver jug into thin china cups on a green lawn, was somebody else, somebody perhaps not so nice but more interesting.

This other Agatha Christie knew a lot about poisons (the use of poison in one of her later books was copied in real life), was fascinated by murder and its methods, and held opinions about the need for capital punishment that are all the more startling because of the naïveté with which they are expressed. She was capable of thinking out criminal plots of outlandish improbability but dazzling cleverness. Who can believe that the ten people in Ten Little Indians (originally and properly Ten Little Niggers), all nursing some guilty secret, would have accepted that mysterious invitation to visit a small island? But such things happen in the world of Mayhem Parva, and once we have taken the leap and accepted them, we can applaud the masterly skill with which the plots are handled. As death after death occurs in Ten Little Indians, we understand that soon only two people will be left, so that one must be the murderer. But there is still a trick to be turned. The book’s last sentences run: “When the sea goes down, there will come from the mainland boats and men. And they will find ten dead bodies and an unsolved problem on Indian island.”

For a long while this extraordinary ingenuity in plotting worked against her success in the movies, which have never found it easy to give full value to such visual clues as the dropped cigarette end or the bloodstained thumbprint, let alone such arcane tricks as those Christie played with verbal misinterpretations or reverse images in mirrors. I have never seen René Clair’s version of Ten Little Indians (1945), but if this justifies the high praise it has received it remains a lonely example among a mass of dismal B films. Even the best of these, The Alphabet Murders, bears such a distant relationship to the original book, The ABC Murders, that it shows how nearly impossible film directors found it to adapt Christie plots. Billy Wilder’s Witness for the Prosecution (1958) was a successful film, but its stage origins were evident.

In 1974, however, Murder on the Orient Express and in 1978 Death on the Nile showed that Christie plots can be transferred to the screen without alteration and with commercial success. And what plots they are. Raymond Chandler said of Murder on the Orient Express, in which not one but all of the suspects are guilty, that it would knock the keenest mind for a loop, and that “only a halfwit would guess it.” The central element of the first death in Death on the Nile, similarly, is so unlikely that only a lunatic would try to carry it out. Nevertheless there is a fascination in seeing it done, and in one of the film’s flashbacks we do see murder done.

We accept and enjoy such stories as if they were fairy tales, something that Chandler didn’t realize. Nothing could be more unlikely than the ritual gathering of suspects in both films, but we are concerned with fictions as strictly conventional as Restoration comedy, not with literal reality. It is entirely right that the paddle steamer going up the Nile should be as luxurious as an Atlantic liner pre-war, that Jack Cardiff’s photography should present an Egypt good enough to eat, without a hint of dirt, and with only a few token swishings to indicate the presence of flies, that the characters should be stereotypes or caricatures.

Here Angela Lansbury is triumphant as an aging hard-drinking nymphomaniac romantic novelist, and one can take no exception to the crooked lawyer (George Kennedy) presenting papers for the heiress (Lois Chiles) to sign in a crowded lounge with people around, and Poirot listening at a corner table. That’s the way people behave in Agatha Christie films. It follows that Albert Finney, the Poirot of Orient Express, is more successful than Peter Ustinov in Nile. Finney looked remarkably like the Poirot of the books, egghead cocked to one side, boot black hair, patent leather shoes. He looks, as his creator said he should, like a hairdresser. The performance is artificial, but Poirot is a totally artificial creation. Ustinov looks simply like Ustinov plus neatly curled mustaches. He goes through what one may call the Ustinov act in a relaxed manner, without making any particular pretense to resemble Poirot. It is a naturalistic performance, out of place in such a film.

For all that, Death on the Nile is a good commercial product, constructed with careful and intelligent artifice. Anthony Shaffer has unobtrusively revised the dialogue where it might sound ridiculous and the director John Guillermin has understood that these two-dimensional figures are interesting for what they do, not who they are. Dame Agatha said that Murder on the Orient Express was the first film made from her work that she had liked, but she would have enjoyed this one too.

And last, the puzzle.

Agatha Christie’s success has not been checked by death. It is not merely that her play The Mousetrap has been running in London for a record twenty-six years, nor that she has been outsold only by the Bible and Shakespeare. Her books have lasted in a literal sense. No more than a handful of other crime stories published in 1920 or earlier are in print today, but The Mysterious Affair at Styles still sells edition after edition. What is it that has made the books last?

Certainly not the quality of the writing, which is at best no more than lively, and at worst as bad as that in the opening sentences of Destination Unknown, a work of the Fifties:

The man behind the desk moved a heavy glass paper-weight four inches to the right. His face was not so much thoughtful or abstracted as expressionless. He had the pale complexion that comes from living most of the day in artificial light. This man, you felt, was an indoor man. A man of desks and files.

The tautology of this, and its general ineptness, do not need demonstrating.

Yet if Agatha Christie was an indifferent writer, she was a most intelligent craftsman, who had considerable sensibility about the form in which she worked. Ira Levin, in an introduction to eight of her plays, points out that she adapted three plays from novels that included Poirot, but eliminated Poirot for stage purposes. This was partly because she felt a distaste for him as she grew older, but partly also because she rightly regarded him as a drag on the dramatic action. In one play she changed the murderer, and in Ten Little Indians altered the ending to let two characters survive. Witness for the Prosecution, which she adapted from a short story, has at its heart an old but brilliantly used stage trick. To see any of the plays is to realize both that dialogue and settings are old-fashioned in the fairy tale sense already mentioned, and also that the mystery in them is devised and concealed with great skill.

This is true also of the best books, most of them written in the 1930s and 1940s. The construction of the puzzle in them is done with unexampled skill. A Christie initiation might begin with The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926), and then go on to The ABC Murders (1935), Peril at End House (1932), and of course Ten Little Indians. Thrillers, like Destination Unknown, should be avoided. Agatha Christie was a mistress only of puzzles pure and complex.

Other bad writers have been skillful craftsmen without lasting like Agatha Christie. Perhaps the nearest one can get to explaining the puzzle of her enduring popularity is to suggest that although the detective story is ephemeral, the riddle’s attraction is lasting. There are those who find the detective story’s origins in the Apocrypha, the story of Oedipus, or Voltaire’s Zadig, but these are scholastic arguments. What is certainly true is that human beings have a passion equally for concealment and revelation. Agatha Christie’s stories appeal strongly to very many people because they fulfill this passion in the world of the fairy tale, a world only nominally linked to reality.

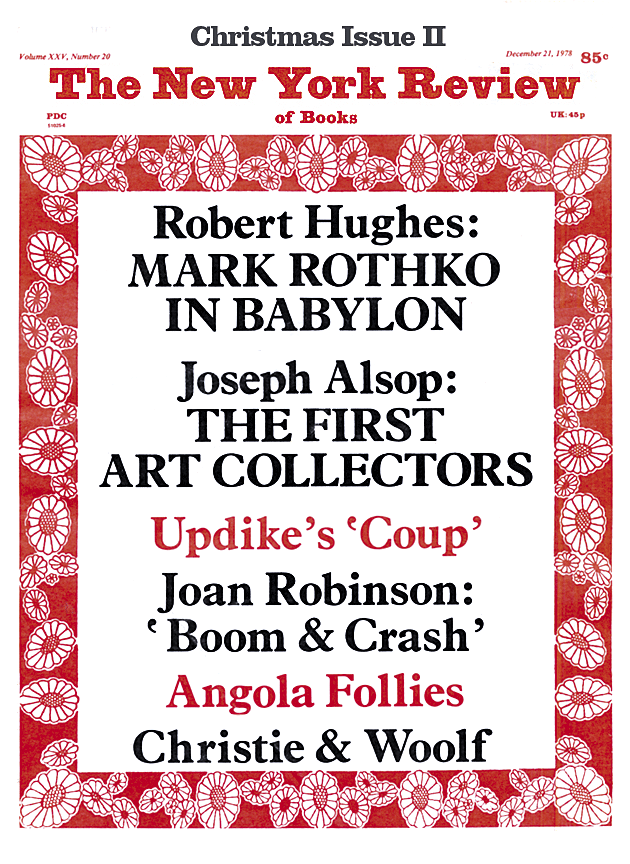

This Issue

December 21, 1978