In response to:

The Starved Self from the February 22, 1979 issue

To the Editors:

I am writing to you on suggestion of Mr. Arthur Rosenthal (Harvard University Press) with whom I discussed my concern about the review of my book The Golden Cage: The Enigma of Anorexia Nervosa (together with three other books) in the February 22, 1979 issue of The New York Review of Books.

Let me first express my satisfaction that this topic was reviewed in such a prominent way. This tragic illness befalls the daughters of intellectual and sophisticated families, such as the readership of the Review, in ever-increasing numbers. It is therefore important that they receive accurate information about this illness.

The review was done by Rosemary Dinnage. She gives a vivid and on the whole accurate description of the clinical picture of anorexia nervosa, with several quotations from The Golden Cage and also from my earlier book, Eating Disorders. She points out correctly that Selvini, the author of Self-Starvation, and I hold similar views on the psychodynamic significance of the anorexic picture. However, Ms. Dinnage fails to recognize important differences. On page 8, column 4, first paragraph, she writes: “Neither Bruch nor Selvini Palazzoli shows much interest in the infantile antecedents of anorexia, preferring to concentrate on the effect of invasive family pressures on the patient in adolescence.” This is the exact opposite of my observations and expressed opinion. I have described this in many papers and in both books from which Ms. Dinnage cites other information. In contrast to what she writes, in the cases I have observed the roots of the illness go back to the earliest experiences in life. I have expressed this in numerous publications including in Eating Disorders, Chapter 4, “Hunger Awareness and Individuation,” and in Chapter 3, “The Perfect Childhood,” in The Golden Cage, specifically pp. 40-43. This is of more than theoretical importance because my whole treatment approach is based on the correction of the consequences of these early faulty experiences.

Much more damaging is the misrepresentation by Ms. Dinnage of treatment prospects. Here again she refers to Selvini and myself as a unit and writes (page 9, column 1): “Neither writer is optimistic about genuine cure in long standing cases.” She continues to speak of “pseudo-therapy,” and “therapists being caught in a double bind.” Again I must say that this is the exact opposite of my experiences and published statements. I thought I had described this clearly in both the books she discusses in the review. In Eating Disorders I have given several detailed treatment histories. I added (page 381): “A higher age of onset and protracted course are not incompatible with complete recovery.” In other words, I consider a genuine cure, with resolution of the underlying issues possible not only in relatively fresh cases but also in those who have been sick for a long time. Such positive results are the outcome of a treatment approach which is geared to the genuine needs of a patient and which I have developed over many years of investigation.

In The Golden Cage I devote the last chapter, “Changing the Mind,” to the description of this successful treatment approach. I quote a few sentences (page 149): “Therapeutic work with these girls is admittedly difficult, slow, and at times exasperating. In a way they have to build up a new genuine personality after all the years of faked existence. There is nothing more rewarding than seeing these narrow, rigid, isolated creatures change into warm, spontaneous human beings with a wide range of interests and an active participation in life.”

I feel these misrepresentations have a damaging effect. It carries to patients and families who read this review the erroneous message that psychotherapy is useless.

Hilde Bruch, M.D.

Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry

Baylor College of Medicine

Houston, Texas

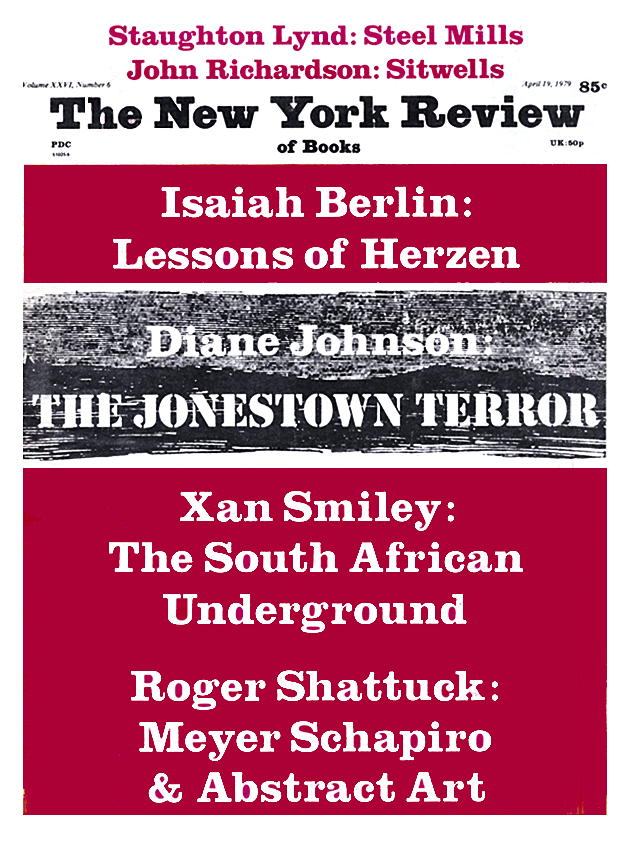

This Issue

April 19, 1979