“A shilling life will give you all the facts,” Auden said mockingly in one of his imaginary portraits. The facts could never encompass the workings of the impetuous heart. Mr. Osborne’s biography, the first in the field, offers chiefly facts; most are not new, unfortunately, and some, as Stephen Spender and others have complained, are not accurate. Except where Auden’s autobiographical remarks come to Mr. Osborne’s aid, the context in which a being might move connectedly from incident to incident is either absent or impoverished. Auden is dangled about on a long line, dipped into one pool after another: always bait and never fish.

Some of the facts are undoubtedly of use. We want to know when Auden experienced agape (1933), when he married Erika Mann (1935), when he went to the United States (January 1939), when he returned to Oxford (June 1972). Our curiosity about his lovers, including one woman—Rhoda Jaffe—is satisfied. But at the end of Mr. Osborne’s book we are a little farther from understanding Auden than at the beginning. Auden had warned of his biographer’s probable failure when he declared, in an essay on Shakespeare’s sonnets, with his usual propensity to foreclose alternative views: “The relation between [a poet’s] life and his works is at one and the same time too self-evident to require comment—every work of art is, in one sense, a self-disclosure—and too complicated ever to unravel.” The springs of any act are complicated, and perhaps especially of acts of writing; still this intricate relation tempts explorers as surely as F.6. Peaks are for climbing.

Auden’s antipathy to biography seems telltale because it is so inconsistently maintained. No anti-biographer has been more biographical in his interests than he. His delight in gossip extended into the past, so that he could announce that Shakespeare, along with Eisenhower, belonged to the “homintern,” and that such pairs as Falstaff and Prince Hal could only be understood as lovers. He wanted to know, and if he could not know, to surmise, all about his contemporaries’ private lives. As he wrote in “Heavy Dates,”

Who when looking over

Faces in the subway,

Each with its uniqueness, Would not, did he dare,

Ask what forms exactly

Suited to their weakness

Love and desperation Take to govern there.

He complained that J.R. Ackerley had never been “quite explicit about what he really preferred to do in bed,” and justified his inquisitiveness by saying, “All ‘abnormal’ sex-acts are rites of symbolic magic, and one can only properly understand the actual personal relation if one knows the symbolic role each expects the other to play.” About Housman he declared he was “pretty sure” that Housman was “an anal passive.”

He was eager, too, to detect and name psychological states and patterns. A whole series of poems is overtly biographical: Auden describes Yeats’s life-long dependence upon women, Matthew Arnold’s filial upbraiding of an age that pretended to take on his father’s authority, Edward Lear’s fleeing to fantasy from his ugly nose, Rimbaud’s abjuring verse as if it were “a special disease of the ear,” the aged Melville sailing “into an extraordinary mildness,” Pascal “doubt by doubt” restoring “the ruined chateau of his faith.” Most of these characterizations suggest states that Auden himself had experienced, and so do his imaginary portraits, which aim to catch their subjects in some giveaway moment when unconscious or secret impulse turns to act. Both types aim to uncover that relation between life and work which Auden had said could not be unraveled. He delighted in the idea that we are secret agents, with guilts—our own and others’—that we had best divulge. In youth he liked simplifications of Freud which could demonstrate by such diseases as “the liar’s quinsy” that the body offered the mind a way to expose itself.

Mr. Osborne has assembled some important details about Auden’s childhood. Auden was at that time bent on becoming a scientist, and won a prize for collecting and classifying shells and insects. This taxonomic urge made him say on his arrival at St. Edmund’s School when he was eight, “I look forward to studying the different psychological types.” He was never happier than when he could put matters into tabular form, as when, in an extraordinary New Yorker review, he compared the stages of life of Leonard Woolf, Evelyn Waugh, and himself. That the comparison was not illuminating did not bother him. He also devoted his childhood to fantasizing about lead mining:

From my sixth until my sixteenth year

I thought myself a mining engineer,

and to adoring large pieces of machinery. In later life he would admit, with that slightly abashed effrontery of his, that these interests had obvious symbolic meanings. Since Mr. Osborne shirks their interpretation, it may be suggested that Auden regarded mining as connected with orality, and dynamos (strength to his weakness) with passivity. He also mischievously recalled how at the age of six he sang Tristan to his mother’s Iseult, as if to encourage his readers to trace his homosexuality to her influence in the routine Freudian way. Whether she instilled his homosexuality is doubtful, but it is certain that she greatly advanced his musical knowledge.

Advertisement

Mr. Osborne thinks that Auden did not really object to biography, but only seemed to. I suspect that he is wrong. For various reasons Auden felt uneasy about having anyone else manipulate the entrails of his experience. Of course they would not get it right. But besides that, he had a well-developed sense of guilt. He did not feel that he had spent his life in the way he ought to have done, and was conscious of much that might be revealed to his discredit. He disliked evasion, but he had evaded. He disliked pretenses, but he had pretended. He disliked imperfection, but was conscious of having too often “slubbered through / With slip and slapdash what I do,” and his excuse, that the Muse “doesn’t like slavish devotion,” did not save him from feeling compunction. He had grown up in the days when poems were thought to be, at least potentially, perfect artifacts, and had some sense of having satisfied himself with imperfect results.

As befitted a lyric poet, Auden’s sexual life was the center of his verse. His inclination was to disclose his own frailties and to force others to do the same. It was a risk but he took it. “I can’t help feeling you are too afraid of making a fool of yourself,” he wrote to a young poet. “For God’s sake don’t try to be posh.” But in shying away from playing subject for future biographical anatomizing, Auden was conscious of having practiced the caution against which he had preached. By early adolescence he knew that he loved boys and not girls. His father found a poem addressed to another schoolboy, Robert Medley, and in a funny-awful scene, called both boys in to say that romantic friendship between young males was fine—he had experienced it himself—provided it had not gone “that” far. Had it? Both boys were able to reassure him. Dr. Auden and his wife became increasingly worried about their son Wystan, and that son increasingly prided himself on loving, as at school on walking, “out of bounds.” Yet he could not tell his parents, and the resultant equivocation mixes with his desired candor in his poetry as well. It encouraged him to write his love poems with their sexual direction indistinct. Readers, like his parents, were “heters” (his word) and needed to be indulged a little. He recognized that evasion to be in a way a virtue, and in later life refused to have his poems included in a gay anthology because they were not intended to be read that way.

In his review of Ackerley Auden remarked that most homosexuals lead unhappy lives. His own stood as model. He confessed to Isherwood in 1938 that he was “a sexual failure.” And yet there had been and would continue to be a series of sexual encounters. One reason for disheartenment may have been that, when he was twenty-three, he incurred, as the result of a pickup, an anal fissure. Mr. Osborne does not comment on it except to say that it necessitated an operation in February 1930 and caused Auden trouble for some years thereafter. The psychic effect was perhaps more serious than the physical. “The discontinuity seems absolute,” he wrote in The Orators in “Letter to a Wound,” a work which shows the encroachment of life upon art better than any precept:

The maid has just cleared away tea and I shall not be disturbed until supper. I shall be quite alone in this room, free to think of you if I choose, and believe me, my dear, I do choose. For a long time now I have been aware that you are taking up more of my life every day, but I am always being surprised to find how far this has gone…. Looking back now to that time before I lost my “health” (Was that really only last February?) I can’t recognize myself.

His wound seems to have fostered Auden’s feelings of erotic insufficiency, of being finally perhaps not lovable. Mr. Osborne recalls, again without comment, the one dream in his life which Auden thought worth writing down:

I was in hospital for an appendectomy. There was somebody there with green eyes and a terrifying affection for me. He cut off the arm of an old lady who was going to do me an injury. I explained to the doctors about him, but they were inattentive, though, presently, I realized that they were very concerned about his bad influence over me. I decide to escape from the hospital, and do so, after looking in a cupboard for something, I don’t know what. I get to a station, squeeze between the carriages of a train, down a corkscrew staircase and out under the legs of some boys and girls. Now my companion has turned up with his three brothers (there may have been only two). One, a smooth-faced, fine-fingernailed blond, is more reassuring. They tell me that they never leave anyone they like and that they often choose the timid. The name of the frightening one is Giga (in Icelandic Gigur is a crater), which I associate with the name Marigold and have a vision of pursuit like a book illustration and, I think, related to the long red-legged Scissor Man in Shockheaded Peter [Struwwelpeter]. The scene changes to a derelict factory by moonlight. The brothers are there, and my father. There is a great banging going on which, they tell me, is caused by the ghost of an old aunt who lives in a tin in the factory. Sure enough, the tin, which resembles my mess tin, comes bouncing along and stops at our feet, falling open. It is full of hard-boiled eggs. The brothers are very selfish and seize them, and only my father gives me half his.

As one of the first English poets schooled in Freud, Auden preserved this dream because he could not fail to recognize in its oneiric shorthand basic elements in his history: his threateningly different (because heterosexual) brothers, the hospital which was the scene of his operation, but which also was connected with his father’s profession; the anal-oral imagery of squeezing and corkscrew. That the eggs given him by his father should be hardboiled seems an ironical allusion to Auden’s necessarily sterile relationships, a sterility which is reiterated in the collation of appendectomy, amputation, and scissors, as well as in the fact that the factory at which he eventually arrives is derelict. His conscious picture of himself was not unlike the unconscious one. He would later disparage himself to friends as “just an old queen” and say he had “put on my widow’s cap.” In a letter to Rhoda Jaffe he remarks, “Miss God appears to have decided that I am to be a writer, but have no other fun,” and he sums himself up as just “a neurotic middle-aged butterball.”

Advertisement

A third matter that Auden was uncomfortable about was his having spent the war years in the United States. He did not acknowledge his regret (“The scrupuland is a nasty specimen”) just as he did not offer confessions (“Confession is like undressing in public; everyone knows what he is going to see”), and later he brazened it out. Here was one of the subjects which he knew that a biographer might easily misunderstand. Probably he had not so much decided to stay in America as to postpone his return to England, though he later claimed a much firmer resolve for his act. Then he met Chester Kallman, on April 8, 1939, fell in love, and knew he could not leave. But following the outbreak of war, as he told me soon after, he offered his services to the British Consulate-General in New York, only to be informed that at present they were not required. The loss of many English poets in the First World War may have affected this official decision, thought it was also true that Auden, flatfooted and queer, did not fit the soldier’s image (Chaeronea to the contrary).

He was again rejected for service when, after having registered in 1940 for the American draft, he was examined in 1942. Meanwhile he had done something else, seemingly but only seemingly unrelated: in October 1940 he returned to the Anglican Church, from which he had separated himself in 1922. His loss of faith had been approximately simultaneous with his beginning to write verse. Auden attributed his return to the death of his mother, but Mr. Osborne helpfully points out that his mother did not die until ten months later. It must have been rather an attempt to recover something of what he had abandoned, to return to his basic English loyalty in spirit while he refused to do so in body.

The thirty-four-year attachment to Kallman may in its early phases have somewhat assuaged Auden’s guilt feelings about expatriation. It was not, however, an easy relationship. The difficulty was patent: Auden was a stay-at-home, Kallman an inveterate cruiser, prone to dart off after someone else at any impulse. From the age of about fifty-five until his death, Auden was often unhappy over Kallman except when they were together, and sometimes then too.

A sequel, if not necessarily a consequence, of the attachment was that Auden, living in America remote from the war, was distracted from one of his principal subjects, politics. The pressure of events which had encouraged that interest in him was reduced by absence from his own country. In his youth he had justified, in a letter to E.R. Dodds, his traveling to war zones on the ground that the poet “must have direct knowledge of the major political events.” His verse had gained strength from this political absorption, however deliberate it had been, and he had written under its prompting many of his best poems, such as “Our Hunting Fathers” and various warnings of impending catastrophe.

But in America his center had shifted, and his poem “September 1, 1939” registers a bewilderment accentuated by his being displaced. The poem declares that everyone is responsible for Nazism, a view so cosmic that Auden later decided it was “dishonest” and left it out of later editions of his collected poems. This attitude has the same mistaken ingenuousness that led him to defend Pound’s having been awarded the Bollingen prize on the grounds that “anti-Semitism is, unfortunately, not only a feeling which all gentiles at times feel but also, and this is what matters, a feeling of which the majority are not ashamed. Until they are, they must be regarded as children….” In trying to rip off masks Auden can take some of the skin away.

A good deal of his exasperation with Yeats—the stalking horse of Auden’s later years—came from his recognition that Yeats had responded to public, contemporary challenges in a way that Auden, for all his downrightness, found increasingly difficult. The notion that poetry might affect events, promulgated by Shelley and demonstrated by Yeats, was inconsistent with Auden’s voluntary exile from his closest political concerns. His gradual insistence that poetry had value as recreation rather than as revelation seemed at least in part a rationalizing of his having expatriated himself. As if afraid that he has become ineffectual, he urges that poetry always is. Fortunately his theory did not prevent his occasionally returning to his old subject, as when the Russians occupied Czechoslovakia and he wrote “August, 1968”:

The Ogre does what ogres can,

Deeds quite impossible for Man,

But one prize is beyond his reach,

The Ogre cannot master Speech:

About a subjugated plain,

Among its desperate and slain,

The Ogre stalks with hands on hips,

While drivel gushes from his lips.

But this, like “The Shield of Achilles,” was exceptional among the relatively private subjects that he more frequently chose.

From the beginning Auden had shown a certain hidden inclination to miss out. Oliver Sacks writes in a volume of tributes to Auden edited by Stephen Spender that Auden had once told him of a recurrent dream he had had:

He was speeding to catch a train, in a state of extreme agitation, he felt his life, everything, depended on catching the train. Obstacles arose, one after the other, reducing him to a silently screaming panic. And then, suddenly, he realized that it was too late, that he had missed the train, and that it didn’t matter in the least; at this point there would come over him a sense of release amounting to bliss, and he would ejaculate and wake up with a smile on his face.*

The pleasure in realizing he has missed out appears to be in keeping with his inner wishes. Something of this attribute appears in his waking life in his fondness for words beginning in “un-,” as if unfulfillments were the law of life. One of his earliest poems, “The Traction Engine,” quoted by Mr. Osborne, is built of such words. The poem with which he started the Modern Library selection of his verse, “The Letter,” shows him to be already the poet of sour grapes. “An artist with certain imaginative ideas in his head may then involve himself in relationships which are congenial to them,” he wrote in Forewords and Afterwords. His examples were from Wagner, but they might have been from his own life—examples of exclusion and dismissal. His friends thought of him as laying down the law, but he thought of himself as pushed around:

Hunt the lion, climb the peak,

No one guesses you are weak.

His life with Chester Kallman may well have been a final cause of Auden’s uneasiness about biography. It ceased to be sexual, Mr. Osborne reports, in the late Fifties, but it remained intense nevertheless. Just what its effect was upon Auden’s later work is still to be assessed. Kallman was a clever man, with a deep understanding of music; Auden always maintained that Kallman’s poetic contribution to their collaborative opera libretti was greater than his own. But at moments he clearly protests too much, as when he reviews Kallman’s verse and praises lines far beyond their deserts. The effect of intermingling a major talent with a much smaller one is not easy to measure, but cannot have been optimal. If Auden had doubts on this score, he never thought of expressing them; but he was unceasingly anxious about his friend’s fanatical roving, hard drinking, and depressive tendencies. His commitment to Kallman was come what come may: he preferred being saintly in his affections to being saintly, like Flaubert, in his absolute devotion to literature. “He was so tired,” Kallman commented after Auden’s death, aware or unaware of how much he may himself have contributed to that fatigue.

The preceding sketch of Auden’s interior drama is consistent with the present state of our information about him, as conveyed in Mr. Osborne’s book and elsewhere. It is of course subject to qualification and amplification from documents, including the poets’ letters, still to be published. But whatever we have yet to learn, it seems clear that Auden was beleaguered. He was a great poet but fell off in his later work for reasons which seem half-consciously sought after. To some extent the trimming of his literary sails, as of his dreams of love, must have been a response to underlying forces in his character at least as much as to external accidents. Happily, even in decline he remained witty, brilliant sporadically, and always readable.

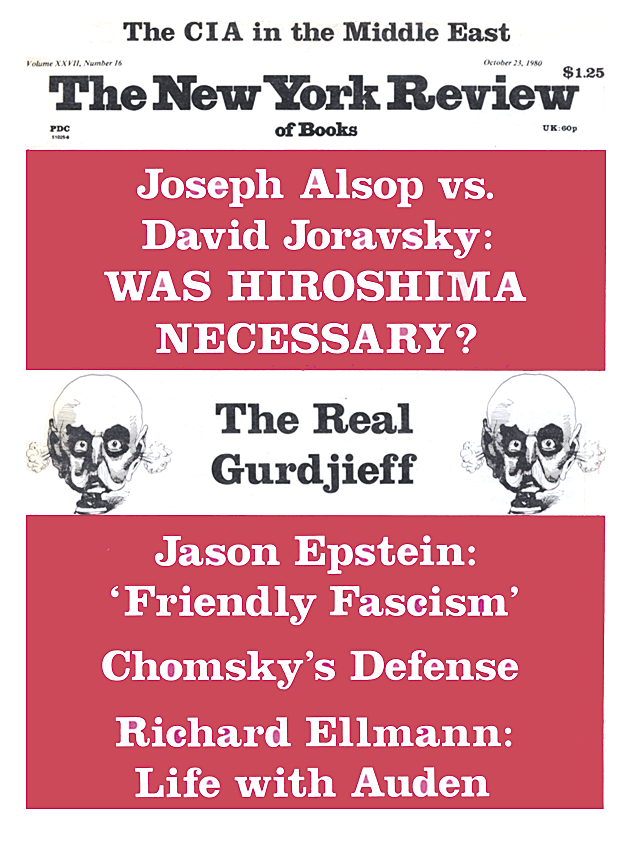

This Issue

October 23, 1980

-

*

W.H. Auden, a Tribute (Macmillan, 1975). ↩