These translations of three poems by Montale were found among Robert Lowell’s papers in the Houghton Library at Harvard. Like all Lowell’s versions of other poets, they are “free”: “Bellosquardo,” for example, is only the first half of Montale’s “Tempi di Bellosquardo.” They were probably written in the mid-Sixties. I want to thank Alan Williamson for finding and identifying the texts.—Frank Bidart

BELLOSQUARDO

Oh how faint the twilight hubbub rising from

that stretch of landscape arching towards the hills—

the even trees along its sandbanks glow

for a moment, and talk together tritely;

how clearly this life finds a channel there

in a fine front of columns flanked by willows,

the wolf’s great leaps through the gardens past the fountains

spouting so high the basins spill—this life

for everyone no longer possessed with our breath—

and how the sapphire last light is born again

for men who live down here; it is too sad

such peace can only enlighten us by glints,

as everything falls back with a rare flash

on steaming sidestreets, crossed by chimneys, shouts

from terraced gardens, shakings of the heart,

the long, high laughter of people on the roofs,

too sharply traced against the skyline, caught

between the wings and tail, massed branchings, cloud-

ends, passing, luminous, into the sky

before desire can stumble on the words.

FLUX

The children with their little bows

terrify the wrens into holes.

Sloth grazes the lazy, thin blue

sky-painted trickle of the stream—

rest from the stars for the barely

living walkers on the white roads.

Tall steeples of poplars tremble

and overtop the hardened hill

surveyed by a statue, Summer—

stonings have made her negro-nosed,

and on her there grows a redness

of creeper, a humming of drones.

The wounded goddess does not look,

and everything is bending to

follow the fleet of paper boats

descending slowly down the trough.

An arrow glistens in the air,

fixes in a stake, and quivers.

Life’s this squandering of banal

occurrence; vain, rather than cruel.

They come back, if a season’s gone,

a minute, these tribes of children

with bow or sling, and find the dead

features unaltered, even if

the fruit they grasped no longer hangs

dead on the young bough. The children

come back again…like this. One day,

the circle that controls our life

will return with the past for us,

distant, fragmented and vivid,

thrown up on an unmoving screen

by an unrevealed projector.

And still the hazy, pale blue vault

vacantly bridges the teeming

watercourse. Only the statue

knows what plunging, lost, entangled

things die in the burning ivy.

All is arched for the great descent:

the channel surges on wildly,

its mirrors crinkle; small schooners

are speeded, caught and wrecked in the

eddies of soap-foamed waste. Goodbye—

stones whistle through the thinning branch,

and gasping luck makes off again,

an hour slips, its faces dissolve…

life is cruel, rather than vain.

BOATS ON THE MARNE

Joy of the bobber heading for the drift

drawn by the small, white arch-stones of the bridge,

the full moon drained of color by the sun—

the boats are nimble on the Marne, retarded

by autumn and the city’s sluggish drone;

and if you touch the meadows with your oar,

the butterfly catcher will reach you with his net;

each ivied swelling and espaliered wall,

a wash of red, retells the dragon’s blood.

It’s easy to hear their voices on the river,

bursts from the banks, the twilight of canoes

and couples gliding under breezy manes

of chestnut trees, but who can hear the filing-in

of seasons, each measured out its brandy for

the vast, untrampled dawn? Where’s the great wait?

How measure their invading emptiness?

This is the dream: a huge and endless day

returns to pour its glare, almost unmoving,

below the bridges, then, at every turn,

man and his good works struggle to the surface,

and float, and vague tomorrow veils its horror…

But the dream was more than this, and its reflection,

still fleeing on the water, swims below

some swinging nest, unreachable, pure air

and silence; and high above the gathered cry

of noonday hangs another morning, morning

over evening and evening over morning—

and the great turmoil is a great rest.

Here then?

Here the enduring color is a mouse

dancing among the rushes, or the starling,

a dash of poisonous metal, sinking in

the smoke-mist of the bank.

“Another day,”

we’ll say. Or what will you say? Ask this day

where it will carry us, this mouth, this river,

writhing into a single gush?

It’s night:

we can go lower, explore the depths, and rest,

until the rising constellations burn.

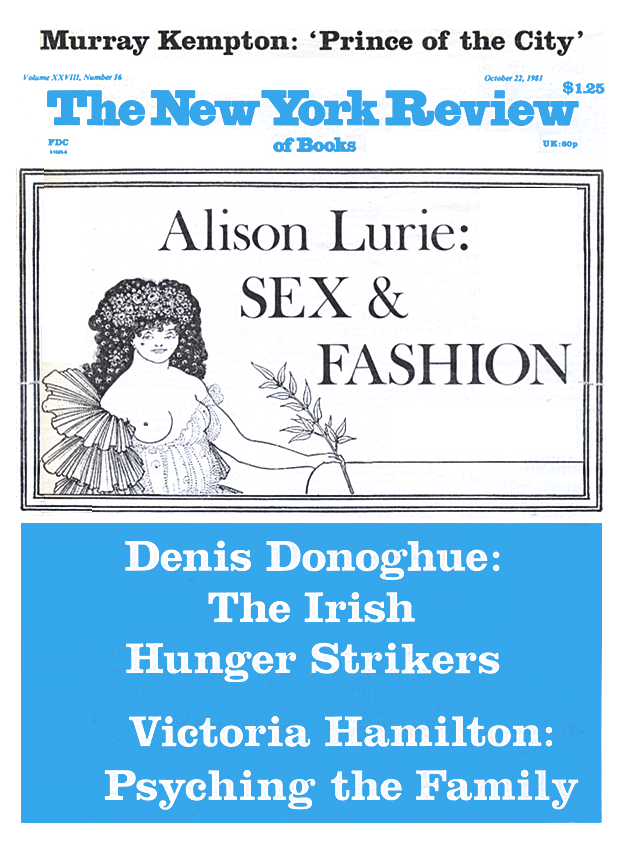

This Issue

October 22, 1981