In response to:

Shakespeare & Co. from the June 16, 1983 issue

To the Editors:

Frank Kermode says that, in calling me a “well-informed layman” in the realm of Shakespeare scholarship, he is being “complimentary, not condescending” [NYR, June 16]. I suppose I should be grateful for the compound adjective, but I can’t help thinking that “well-informed writer” would have been nicer. His noun implies that he, unlike an ordinary layman (such as I), has taken Holy Orders. I’ve never thought that literature was the special preserve of any class, clerical or lay. I acknowledge that The Book Known as Q is the work of an amateur, in the sense of a lover of learning, rather than that of a tenure-holder in the groves of academe, but even professors are only as good as their scholarship.

As a layman, I make no claim to infallibility, but why does Mr. Kermode dispute the fact of Southampton’s generosity to Shakespeare? Forgetting the amount, which I’ve said we cannot know, and admitting that Davenant and Rowe are unreliable sources for details, the actuality of Southampton’s generosity to the poet (which is all my book maintains) is also supported by contemporary evidence: (1) John Florio’s “pay and patron-age” tribute to Southampton in The World of Words (1598): “But as to me, and many more [a probable reference to Shakespeare], the glorious and gracious sunshine of your honour hath infused light and life”; and (2) even more important, Shakespeare’s words in his dedicatory letter to The Rape of Lucrece (1594): “The warrant I have of your [Southampton’s] honourable disposition”—both of which I cite. Mr. Kermode seems to have read and reviewed my book selectively. He even states that “his [Stephen Booth’s] book is not mentioned,” whereas I describe “Stephen Booth’s edition of the sonnets,” and quote from it (p. 50); I list the author, title (Shakespeare’s Sonnets), and publication date (p. 309), and give four references to specified pages in Booth’s book.

I feel encouraged, however, by Mr. Kermode’s statement that “if Booth ever said that he regards the Sonnets as merely ‘literary exercises’…I should want to disagree with him.” Booth’s text (p. 432) reproaches writers (like me) who “have been concerned with finding out what Shakespeare was talking about, what the occasion of the Sonnets was, rather than with the literary experience the poems evoke in us, and/or a Renaissance reader.” This, unfortunately, is the current party line of the academic Shakespeare Establishment: (a) treat each Sonnet as a purely “literary experience”; (b) flunk anyone, especially a layman, who claims that on occasion the poet actually writes about himself, as in Sonnet 110, “Alas, ’tis true I have gone here and there”; and (c) expel anyone who regards it as well nigh impossible to determine what experience a poem may have evoked in a Renaissance reader. On the perplexing question of homosexuality in the Sonnets, Booth slyly states that “Shakespeare was almost certainly homosexual, bisexual, or heterosexual. The Sonnets provide no evidence on the matter.” On the contrary, the Sonnets are the sole reason for raising the question, and provide all the evidence of homosexuality there is, especially Sonnet 20, the Master-Mistress sonnet. If the Sonnets did not exist, what grounds would there be for the allegation? To rule out biographical consideration of the Sonnets totally, as Booth does, is to fall into the Antibiographical Fallacy. I’m reassured and pleased to know that Mr. Kermode would disagree with such an approach.

Robert Giroux

New York City

Frank Kermode replies:

I did not argue that Southampton was not generous to Shakespeare, only that the eighteenth-century tale of an enormous gift has no authority.

Mr. Booth edited the Sonnets, and also wrote a book about them. It is called An Essay on Shakespeare’s Sonnets (Yale University Press, 1969). I said that Mr. Giroux did not mention this book. I was right to say so, for he did not.

Whether Mr. Booth thinks the Sonnets mere literary exercises is a question that could most easily be settled by asking him. Nothing Mr. Giroux now adduces inclines me to change my guess that he doesn’t.

On well-informed laymen: I know a bit about publishing; Mr. Giroux is a publisher of great eminence. If he were ever to call me, in respect of his profession, a well-informed layman, I should be flattered.

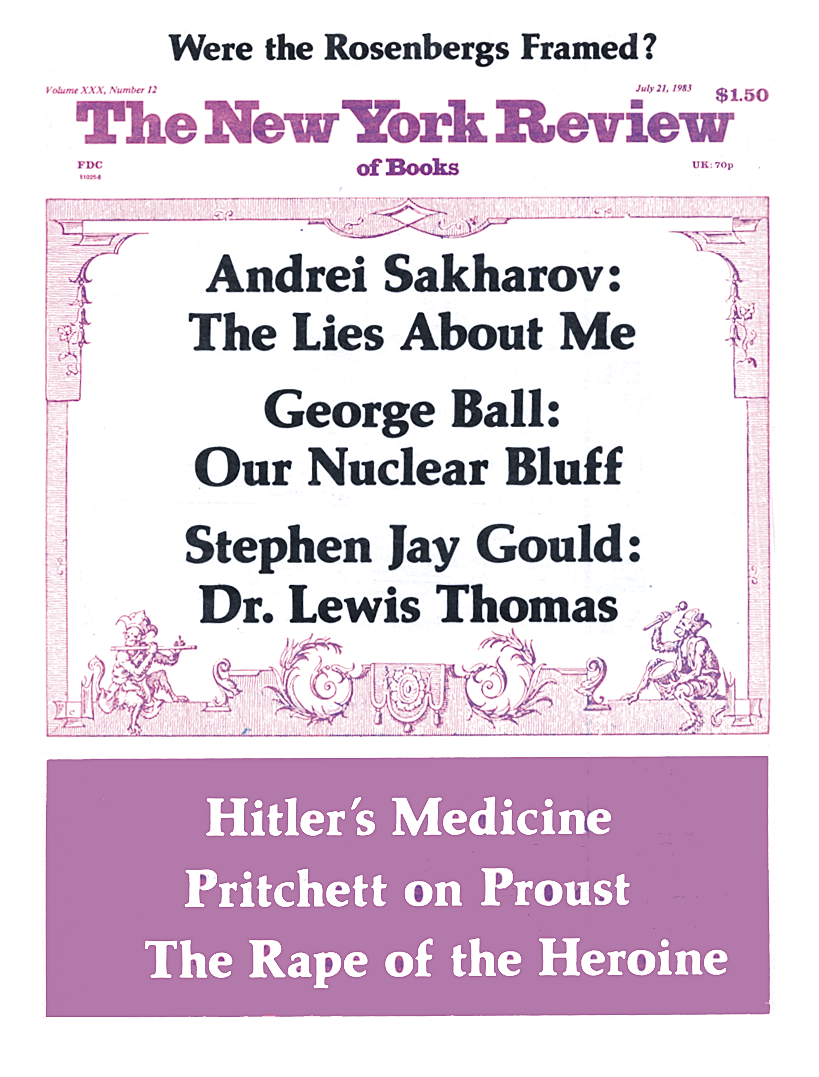

This Issue

July 21, 1983