It is not necessary to hope in order to undertake, nor to succeed in order to persevere.

—Pascal

1.

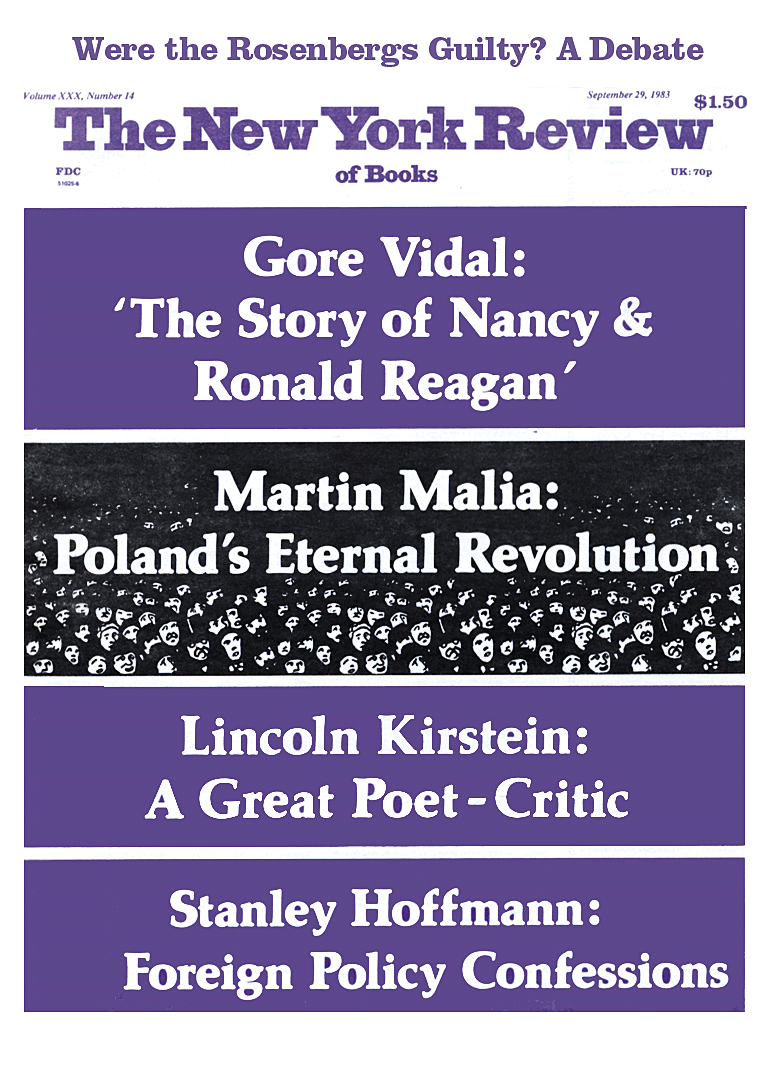

“Solidarity, the first free labor union in a communist country,” the Western press has begun most commentaries on Poland since the great strike of August 1980. True enough, but by no means the whole truth. During sixteen months in the open, and now twenty months underground, the union Solidarity appeared increasingly in two other guises as well: since its employer was not a mere capitalist but a communist monolith, it inevitably became a movement for the emancipation of all of society from the party-controlled state; and since this regimen was a foreign imposition, it edged toward being a movement of national liberation from Soviet Russia.

All this, of course, could not be declared openly, but it could still be tellingly conveyed through the rich language of Polish symbolism. It was first intimated during August itself in Solidarnosć’s famous emblem, whose jagged letters of red against a white background represented workers marching on strike and carrying the red and white flag of Poland. A more religious message of national death and rebirth was enunciated in the great crosses that the union insisted be erected in Poznan, Gdansk, and Gdynia for the fallen dead of “people’s” Poland between 1956 and 1970. Or as the cabaret ballad that became the anthem of the sixteen months of freedom rousingly proclaimed: “Let Poland be Poland.”

But what is this Poland so fervently invoked on all sides, even by General Jaruzelski, who called his martial law a regime of “national salvation”? Fortunately, a large number of recent books contribute to making “Polishness” accessible to outsiders. The historical perspective of this literature is especially apposite since it contravenes the conventional wisdom about Solidarity expressed in journalistic accounts, concentrating on events since 1980.

The conventional wisdom holds that Solidarity was simply what it said it was: an independent labor movement of the sort that any mature working class would desire. An elaboration of this thesis, which looks no farther back than the last decades, holds that Polish communism, though a debased form of socialism, had nonetheless industrialized a backward society and imbued its new proletariat with the idea that the regime is, or ought to be, a worker’s state. Solidarity was thus merely taking the regime at its word and attempting to realize, at last, its professed ideals.1 This thesis has the merits of simplicity and of attractiveness to foreigners, because workers’ democracy possesses a broad and progressive appeal, whereas it is much more difficult to peddle “Polishness” abroad, because this does, or can, suggest a retrograde and obscurantist parochialism.

The defect of the conventional thesis, however, is that communism brought industrialization everywhere in Eastern Europe, and first of all to Russia, yet nowhere else did there emerge such a widespread and enduring movement for democracy as Solidarity, not even in Hungary or Czechoslovakia—and least of all in Russia. The decisive variable in the Solidarity mix, therefore, must be not industrialization but the Polish tradition. And indeed, though in the first instance a union, Solidarity was also the eternal return, but in nonviolent form, of the classic Polish insurrectionary struggle for independence and democracy, or for the “self-governing republic” as the union’s program put it in a clear reference to the historic Polish Commonwealth.

Anyone acquainted with the Poles cannot fail to be struck by their awesome historical memory. That this memory often contains as much legend as fact is of secondary importance; the main point is that the Poles live out their contemporary destiny as part of history to a degree unparalleled elsewhere in Europe. There is indeed perhaps no more striking example of the primacy of national or cultural tradition over social or class consciousness than that of the Poles—unless it be that of their longtime codenizens in the erstwhile Commonwealth, the Jews.

For Poland is not a country, such as England or even vulnerable Czech Bohemia, that has been in exactly the same place throughout its history. It has been all over the map of Eastern Europe, from the Baltic to the Black Sea and back, and from the Oder to beyond the Dnieper and then again back; major cities long Polish, such as Wilno and Lwów, are now Soviet, and cities recently German, such as Gdansk and Wroclaw, are now Polish. Poland is thus less a place than a moral community, an idea or an act of faith, lived almost compulsively by a people oriented less toward the here and now than toward an idealized past, in order to redeem an intolerable present and to bring forth a more glorious future—a people again a bit like the Jews.

Specifically, the Polish drama lies in an unprecedented descent from national grandeur to national annihilation. At its height in the sixteenth century, Poland came near to establishing itself permanently as one of the great powers of Europe, and perhaps the freest among them, only to lose everything in the partitions of the eighteenth century and to plunge into an abyss which threatened the nation with irrevocable servitude, indeed extinction. Ever since, the aspiration of the Poles has been to refute the apparently final verdict of history and restore their national greatness. This quest, moreover, produced a cultural tradition that is a somewhat bizarre and uniquely Polish amalgam of libertarian democracy, Baroque Catholicism, and Romantic patriotism. But to explain all this one must outline the Polish story, taking as the main guide Professor Davies’s magisterial God’s Playground: A History of Poland.

Advertisement

This two-volume work is a tour de force in every way. It is critical of Polish patriotic myths, yet sympathetic toward their deeper meaning, as its title, an old proverb, implies; for “God’s playground” means that Poland has been the plaything of the gods or of a mischievous fate, as well as, just possibly, the stage for an authentic divine comedy. The work is encyclopedic in scope, alternating topical with chronological sections to produce an undogmatic and cohesive analysis, appropriately addressed to the preconceptions of readers who live “in islands or on half-continents of their own.” Superbly written, moreover, it will be the definitive English-language history of Poland for many years to come. In the present it need only be supplemented by Professor Fedorowicz’s admirably presented collection of articles by leading Polish historians, such as Bronislaw Geremek, Henryk Samsonowicz, and Jòzef Gierowski, all active in the “renewal” of 1980-1981.

2.

The story these books have to tell began modestly a millennium ago, with the first Poland, that of the Piast dynasty. In the tenth century, the Slavic people of the fields, the Polanie, in order to resist eastward German expansion, formed a loose polity between the Oder and the Vistula. The main innovation of this new realm was to receive legitimizing Christian baptism, in 966, under the direct jurisdiction of Rome rather than through the Germans of the Holy Roman Empire. An independent royal crown soon followed, thus making Poland wholly autonomous, in contrast to kindred Slavic Bohemia, which developed as part of the Empire.

After the usual vicissitudes of collapse and renewal characteristic of barbarian domains, involving notably the loss of Silesia and Pomerania to the Empire, by the fourteenth century the Piast kingdom had come to cut a respectable figure on the European scene. Its lands were populous and prosperous; towns had appeared, fed largely by German and, later, Jewish immigration; the realm even had its own university, at Kraków. By the time of the last Piast, Casimir the Great, Poland had become a kind of outer Bohemia, a mature state of middling size beyond the Empire and the easternmost outpost of Latin Christendom, or the antemurale Christianitatis as it came to be called. An honorable record, no doubt, but not a particularly original one.

The ultimate historical fate of this first, western Poland, however, was to serve as the nucleus of a second, much vaster nation, extending far into the east as the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. This eastward orientation was the beginning of Poland’s true originality and European greatness, and the source of a collective consciousness that endures to this day.

This new direction came about in 1386 with the marriage of the Piasts’ heiress to Jagiello, grand duke of the Lithuanians, the last pagan people in Europe. An alliance was thereby forged against the crusading Teutonic Order, which had been established in the previous century to subdue the pagan Prussians along the Baltic coast between Danzig (Gdansk) and Königsberg. Since the Order now threatened the Lithuanians, the latter accepted baptism peacefully from the Poles, and the two nations together, at the Battle of Grunwald (Tannenberg) in 1410, broke the power of the Teutonic Knights and made Prussia a vassal of Poland; thus Poland was made secure in the west.

The union of Poland and Lithuania had even more important consequences in the east. For the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was enormous, three times the size of Poland, and included not only ethnic Lithuania but what is now Bielorussia and the Ukraine. It was in effect a “Russian” state, to use an anachronistic term, and, except for Lithuania proper, Orthodox in religion. Lithuania had grown so large because its grand dukes proved a better shield for their Orthodox subjects against Tartars and Muslim Turks than the other Russian state, Muscovy.

The union of Poland with Lithuania had three momentous consequences: the new unit became the largest state in Europe at the time; Poland was transformed into a multinational and multiconfessional community; and it was set on an inevitable collision course with Muscovy over the grand duchy’s Orthodox lands. But until the balance tipped toward Moscow in the mid-seventeenth century, this expanded Poland had its golden age.

Advertisement

At first the bond between the two nations was only a personal one under the Jagiellonian dynasty. In time, however, the Lithuanian grand duchy’s nobility became Polonized in speech and culture and, usually, Catholic, even in the Orthodox provinces. Ultimately the weaker party, Lithuania, under pressure from Ivan the Terrible, was driven to accept permanent and organic association with Poland at the Union of Lublin in 1569.2 The historic Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was at last fully formed. Or, as Professor Davies insists, the proper term is “republic,” not only because the Rzeczpospolita, as it was called, means literally res publica, but even more because its institutions were in fact more republican than monarchical. For the most remarkable thing about the new state was less its international weight than its extraordinary internal constitution—still little understood in the West.

That constitution rested on the hegemony of a single estate, the szlachta, or nobility. This group, to be sure, must be subdivided according to wealth, power, and prestige into a small group of great “magnates” and an enormous group of “gentry,” in part landed and in part almost as impoverished as the peasantry. Yet important though these distinctions are, they should not obscure the fact that legally and politically the szlachta constituted a single estate, all of whose members enjoyed identical rights. A genuine egalitarianism thus prevailed within the group as whole, which made it the “noble nation.” This body was huge for the period, eventually comprising almost 10 percent of the population—the largest nobility in Europe.

The szlachta by its very size came to dominate all other estates, subordinating the towns to its interests, transforming the Jews into its agents, and enserfing the peasantry. Yet it would be anachronistic to decry such lopsided privilege, for constitutional practices, wherever they developed in Europe, did so as a “trickle down” from lordly prerogative, beginning with the barons of Runnymede. At the time, throughout Europe east of the Elbe, a crushing predominance of the nobility, particularly in relation to the peasant serfs, was only routine. The point is that elsewhere, in Russia and Prussia, similar arrangements became the basis for autocracy; in Poland this “nobleman’s paradise” became the basis for constitutionalism. Indeed, the conventional term “noble democracy” is not too strong, for the proportion of people entitled to vote in the Polish republic was one that England, for example, would not surpass until the Reform Bill of 1867.

This “republic of nobles” was able to establish its power because, until very late, Poland lacked neighbors dangerous enough to make royal absolutism a necessity for national survival. Beginning in the fourteenth century the szlachta gradually wrested from the Crown the cardinal rights of due process of law and government by consent. By 1433 the statute of Neminem captivabimus, similar to the English Habeas corpus of 1679, guaranteed full personal inviolability to all nobles.

But the decisive turning point came in 1454 with the Statutes of Nieszawa, by which the king, seeking in the gentry a counterweight to the magnates, conceded to the szlachta as a whole the principle that there would be no new laws, taxes, or declarations of war without the consent of grass-roots noble assemblies, the sejmiki or “dietines.” By the end of the century this led to the convocation of the first central Sejm, or Diet, of delegates from the dietines, as a permanent check on the Crown.

The final touches were put on the system in 1573. By then the republic was deeply engaged in the most variegated Reformation in Europe, ranging from Lutheranism and Calvinism to Socinian Unitarianism and other radical sects, all patronized by the independent-minded szlachta. Their sense of individual rights, therefore, produced a statute of general religious toleration, which made of Poland that rarity in contemporary Europe, “a state without stakes.”

In the same year the monarchy, already subject to choice by the nobles, on the extinction of the Jagiellonian dynasty became formally elective and bound by an explicit constitutional contract to uphold the “golden freedom.” Even more extraordinary, every noble had the right to participate personally in the election, and at each interregnum many thousands would in fact do so. Sovereignty was now totally vested in the “nation.”

In consequence, the center of gravity of the system remained with the grass-roots dietines, which instructed their delegates so carefully that in practice the Sejm could act only by unanimity. At first this meant merely that hard bargaining to reach a consensus was necessary for all legislation, a not unreasonable requirement in such a large and diverse state. Nor is this arrangement without parallel elsewhere: it is similar to the confederative constitution of the contemporary Dutch Republic, or to the American Continental Congress when the thirteen colonies were still sovereign states.

In 1652, however, the Polish version of consensus went off the deep end: it became the liberum veto, by which a single delegate could “explode” any session of the Diet and void all previously adopted legislation. The antidote to this practice was equally dangerous. It consisted in the institution of “confederation,” a right of armed civil disobedience by a group of nobles, operating through majority vote outside the vetobound Sejm, to seek a redress of grievances. Again such a “right of resistance” is not without logic or parallels elsewhere. Still, in conjunction with the liberum veto, it proved to be increasingly costly. It gave first to the magnates, who played on the gentry’s horror of monarchical absolutum dominium, the ability by the mid-seventeenth century to checkmate the royal executive. By the eighteenth century, it gave to neighboring powers the capacity to intervene through their pawns in all of Poland’s affairs.

At the beginning the “golden freedom” had been based on the unexceptionable principle of “Nic o nas bez nas,” or “Nothing about us without us.” Later this became the paradoxical boast: “Nierzadem Polska stoi,” or “By unrule Poland stands.” Read one way this could mean that Poland’s strength lay in her liberty. But read another way the word for “unrule” could mean “anarchy”; and when matters reached this point, the republic’s undoing was at hand.

Disaster first struck in the “Deluge” of the mid-seventeenth century. In 1648 a bloody Cossack and peasant revolt in the Ukraine delivered half of that region to Muscovy, thereby tipping the balance against Poland in the east. In 1655 the Swedes invaded from the north on a dynastic pretext and, abetted by nobles who hoped that a change of kings would enhance their liberty, overran the entire country. And in 1657 the Duchy of Prussia was transferred to Brandenburg, thereby setting a western rival to Poland on its way to greatness. But in a desperate effort the noble nation pulled itself together again, and in 1683, in the republic’s last and most glorious hurrah as a great power, dispatched King Jan Sobieski to rescue besieged Vienna from the Turks, thus saving all Europe from that “scourge of Christendom.”

Amid these vicissitudes, a new national consciousness emerged through the equation of Pole with Catholic, at least for the half of the population that was both. Under the combined onslaught of Lutheran Swedes, Orthodox Muscovites, and Muslim Turks, the old luxury of “dissidence” came to appear as a potential for treason; and the szlachta returned en masse to the Roman fold, now characterized by the rigoristic yet emotional and theatrical piety of the Counter-Reformation. Yet whereas in Bohemia and Hungary Catholicism had been reinstated in significant measure by force, in Poland its restoration was voluntary, and without persecution of the still numerous dissidents.

This willing reconversion goes far to explain the unique link that has since existed in Poland between Catholicism and national sentiment, and with the “golden freedom” as well. To symbolize the new Polish covenant, in 1656, in the midst of the Deluge, King Jan Kazimierz dedicated Poland to the Virgin of Czestochowa, just delivered from the Swedes by a “miracle,” and proclaimed her “Queen of Poland.” And astounding though it may seem, this Baroque title is taken literally by innumerable Poles to this day, for in time it came to signify that in the absence of a legitimate and free Polish state, Mary as the Mater dolorosa is sovereign and the Church is her regent; which is why Lech Walesa always wears a badge of the Virgin on his jacket.

The Deluge was only the prelude of worse to come, the partitions. The pitiless logic of geography leaves room for only one great power in the open plains of Eastern Europe, and this prize it long seemed would be Poland’s. After 1700, however, the military autocracy of Peter the Great had irretrievably won it for Russia; and by 1717 the republic had become his satellite. But this Russian preponderance eventually alarmed Prussia and Austria; so Catherine the Great had to pay the two of them off in 1772, with the first of three amputations of Polish lands.

The shock of this atrocity brought to fruition within the remainder of the republic a reform movement that was already building under the influence of the Enlightenment. It was now recognized that if Polish freedoms were to be preserved, they must be divorced from the liberum veto and the right of confederation; they must be extended to categories below the nobility; and they must be combined with a strengthened, hereditary monarchy possessing adequate armed forces.

This program was put through in the Great Diet of 1788 and embodied in the Constitution of May 3, 1791. Poland thus made her moral equivalent of the American and French revolutions, but by reinforcing rather than by attacking royal power. Poland’s rightful place in the “age of democratic revolutions” is expanded upon in The American and European Revolutions, edited by Professor Pelenski, a collection produced for the American bicentennial of 1976 and composed of essays by Polish and American scholars.

Yet for Poland, less lucky than her Western fellows, revolution brought not liberty but ruin. For Russia and Prussia, alleging “Jacobin subversion” in Warsaw, moved in to crush the new order, and by the same stroke reduced the republic to a rump through a second partition in 1793. The following year the Poles answered with their first modern insurrection: a desperate effort under General Tadeusz Kosciuszko (who had previously fought in the American War of Independence) to restore the Constitution of May 3. Indeed, Kosciuszko went beyond that document and, in the Manifesto of Polaniec, proclaimed the emancipation of the peasants from serfdom in order to promote national unanimity around the “cause.”

The revolt, of course, failed, and May 3 and Polaniec remained no more than symbols. Yet these symbols set the agenda of Polish politics for the next century, and in a sense to the present. The agenda was “independence and democracy,” or the modern perfection of the old republic, to be achieved with, or so it was hoped, Western aid against Eastern despotism. At the time, however, the outcome of the revolt was “finis Poloniae,” the extinction of the republic in 1795 through a final partition among Russia, Prussia, and Austria—a deed of international lawlessness without parallel in European affairs until the twentieth century.

3.

The partition of 1795 is the great caesura of Polish history, the catalytic trauma for all that has followed. At first the Poles, incredulous, were convinced that the restoration of the republic must be at hand. But each time they tried to dig themselves out, they only dug themselves in deeper. Their insurrections thus unfolded for more than a century: 1830, 1846-1848, 1863, 1905.

Yet this period of travail had its positive aspects; the growth of the “noble nation” into a modern national community embracing all classes of the population, and the transformation of “szlachta democracy” into democracy tout court. Nationalism and democracy are, to be sure, staples of nineteenth-century history everywhere in Europe, but circumstances gave them a special urgency and edge in the lands of the partitioned republic. For the primary struggle for independence could be waged only by equally vigorous pursuit of a second goal, that of social justice within the national community. This meant that Polish nationalism took a basically radical direction in a way that, say, German or Russian nationalism usually did not. Yet this leftist tendency was in no way hostile to traditional values; for the partitions had precociously disestablished the Roman Church and thus made it the focus of society’s resistance to alien and despotic state power—rather like the case of Ireland.

Poland’s new radical vocation became apparent immediately after 1795 with the participation of General Henryk Dabrowski’s legions in the wars of Napoleon; their battle hymn, a mazurka proclaiming that “Poland has not yet perished so long as we still live,” is still sung as the national anthem. The bet on Napoleon indeed brought forth the creation of a middle-sized Duchy of Warsaw in 1807. But with the Emperor’s defeat, the Vienna peace settlement of 1815 awarded the duchy to Russia as the “Congress Kingdom,” in what amounted to a fourth partition by which Moscovy acquired, at last, the lion’s share of the old republic.

With the creation of the Congress Kingdom, the Polish cause became above all a struggle against Russian autocracy. The kingdom had its own army and a modest constitution, both granted by Alexander I in deference to Polish tradition but by no means adequate to his new subjects’ desires. So after the Revolution of 1830 broke out in Paris Warsaw rose up in the November Insurrection, with the vague hope of Western support and in the name of both genuine constitutionalism and the pre-partition frontiers of 1772. But no aid was forthcoming, and the Poles were crushed in a disaster as great as that of the partitions. The Congress Kingdom was incorporated into the Russian Empire, while its elites went into exile in Paris.

Among the members of this “Great Emigration” the Polish cause assumed the form of a grandiose Romantic millenarianism and messianism, which is the subject of Professor Walicki’s rich and penetrating book Philosophy and Romantic Nationalism: The Case of Poland. The emigration was highly diverse, ranging from constitutional monarchists to radical republicans and outright socialists; but all participated in some measure in a creed which was an extraordinary blend of lyrical nostalgia and prophecy, of German philosophical idealism and historicism, of French revolutionism and socialism, of Bonapartism and politicized Catholicism, all combined with invocations of the old republic and even of alleged Polish origins in a primitive peasant commune.

Numerous variations on these themes were set forth, in texts that often became classics, by a remarkable generation, including poets such as Adam Mickiewicz or philosophers such as the prominent left Hegelian August Cieszkowski. But the most forceful idea in all this ferment was that Poland, because of the exemplary value of her old institutions and of her exceptional sufferings since the partitions, had become the “Christ among nations,” who had died only to be resurrected, and whose rebirth would bring the redemption of all Europe in a universal revolution for liberty, democracy, and fraternity among the peoples.

Clearly, this is a very heady vision, and just as clearly it is an ideology of compensation for failure in the real world. Yet it would be a mistake to write it off as simply a Polish aberration. For the Revolution of 1830 ushered in throughout Europe, and from Mazzini to Michelet to Marx, an age of secular millenarian expectations, of belief in a Second Coming of 1789, which would bring the earthly, social salvation of mankind—a groundswell of liberal-democratic-national hope that culminated in the “Springtime of Peoples” in 1848.

Yet there is a distinctively Polish accent in this secular chiliastic chorus; and that is the theme of solidarity, among all classes around the historic nation, as the true path to democracy; and the concomitant belief that a faith born of suffering can overcome obstacles that would daunt mere realists. Through the great texts of their Romantic poets—Mickiewicz, Juliusz Slowacki, Zygmunt Krasinski—the Poles are still intimately familiar with this message. Indeed, without it, Poland, placed where it is, would long since have given up on trying “to be Poland.”

The long awaited Springtime of Peoples touched Poland only partially, in abortive actions between 1846 and 1848 in Austrian Galicia and Prussian Poznania. But Russia’s defeat in the Crimean War of 1854-1856 obliged even czarism to reform, and this at last gave the Polish heartland its chance to act on the visions of the emigration. The result was the January Insurrection of 1863, the most heroic and tragic of all Polish risings.

After 1830 Polish democrats had explained the defeat of the November Insurrection by the nobility’s failure to do anything adequate for the peasants, who, though they had been legally freed from serfdom by Napoleon, remained economically dependent on the szlachta because they had been granted no lands of their own. This criticism, in conjunction with the impending Russian reform, now made justice for the whole nation the center of the Polish cause. So the democratic “Reds” rapidly overran the aristocratic “Whites” with increasingly radical programs for peasant emancipation, as a prelude to an armed struggle for independence with, it was hoped, Western and even Russian revolutionary aid. Inevitably, St. Petersburg resorted to repression; so in 1863 the Reds rose up, dragging the Whites along with them in a reflex of national solidarity.

The insurrection became more radical still because the Congress Kingdom now had no army or state structures of its own as it did in 1830; the only recourse therefore was guerrilla warfare against the Russian forces. The war led to the creation of a veritable underground state which even more daringly taxed and conscripted a willing population. This underground even undertook to promulgate “legislation” emancipating the peasants by giving them land and without compensation for the nobles. Through these extraordinary measures the revolt was kept going for a year and a half, in both Poland and Lithuania, against the mightiest state in Europe. But, again, no foreign aid was forthcoming, and Russian strength could only prevail.

The result this time was catastrophic. Conservative Russia imposed on Poland the “Reds’ ” radical program of peasant emancipation in order to destroy the szlachta by undermining its economic base. The nobility began to wither away as a class, and its members, entering the liberal professions, became an intelligentsia devoted, along with the Church, and at times against it, to keeping the Polish tradition alive through cultural rather than political activity. But even Polish language and culture were proscribed, through a campaign of forced Russification of education and public life, in a deliberate effort to obliterate Poland’s identity. Concurrently, Bismarck’s anti-Catholic Kulturkampf pursued the same aim in the Prussian partition.

The Poles, for their part, gave up on Romantic insurrection as too costly for national survival. But they did not give up on being Polish; and the new patriotic watchword became “organic work,” known also as “Warsaw positivism.” This meant they renounced the struggle for independence as quixotic, and concentrated instead on hard work for the intellectual, professional, and economic advancement of the nation. Only through such practical, “positive” progress could Poland hope to survive as a community between Russia and Germany. “Organic work” has remained a major tradition ever since, in opposition to the heritage of 1830 and 1863—as in the “neopositivism” of the Church after 1956 under Cardinal Wyszynski. It is a phrase that remains current in Poland today.

But the old Romantic demons refused to die, and by the beginning of the twentieth century, in new industrial conditions, they were back under the name of revolutionary Marxism. The minority party of Social Democrats, led by Rosa Luxemburg and Felix Dzerzhinsky, were doctrinaire internationalists who rejected Polish independence as economically retrograde; and most of them later became communists. But the majority Socialist Party, led by Józef Pilsudski, held that proletarian revolution also meant independence. Indeed the socialists made independence the prior condition for worker emancipation; and it is this more familiar position that won over the popular masses.

At the same time the modernization of Polish society produced a cautious middle-class party in Roman Dmowski’s National Democrats. The adherents of this Endecja were classical liberals in that they opposed Pilsudski’s radicalism in favor of cooperation with Russian constitutional democrats, the Kadets, for general reform of the empire and with the demand only of autonomy for Poland. But they were also defensive, resentful chauvinists who construed Polish patriotism, hitherto generous and cosmopolitan, as a creed of ethnic “egoism,” a Social Darwinian mutant of nationalism typical in Europe at the time.

This political revival, in 1905, produced a new insurrection under Pilsudski’s socialists, a new underground state, and a new defeat. There matters rested until World War I at last gave Poland its chance. But by an irony of the gods, except for the modest legions of Pilsudski (who had now abandoned socialism), the Poles played no part in their liberation. Independence came about in 1918 because, improbably, the three partitioning empires of Russia, Germany, and Austria collapsed simultaneously. Pilsudski stepped into the void and established the Second Republic, as it was called, with May 3 as its national day and the March Dabrowski of 1798 as its anthem.

Yet the infant state had its great heroic moment. In 1920 Lenin’s reborn Russians headed west, “over the corpse of White Poland to world conflagration.” But Pilsudski and a united population had the immense satisfaction of routing them at the gates of Warsaw, in a “miracle of the Vistula” that also fell on the major feast of the Virgin. Thereby the blessings of Leninism were reserved for Russia until 1939, and the Poles felt that they had again saved all Europe, à la Sobieski, in an update of their role as the antemurale Christianitatis.

4.

But at this lyrical moment beloved of all Poles, a vexing question arises: Why is it that restored Poland, with its vaunted constitutionalist heritage, was not more successful as a modern democracy, and in closer accordance with the lofty Wilsonian canons of the day? Professor Polonsky’s Politics in Independent Poland, now a standard book, provides some down-to-earth, Central European answers.

It was, first, no easy matter to weld the three segments of Poland into a single community after 150 years apart, a problem intensified by the destruction of six years of war. Nor was the interlude of independence at all smooth, marked as it was by two depressions, as well as by increasing international insecurity; since neither Germany nor Russia ever accepted Poland’s frontiers. Then the constitution of 1921 had been cast in ultrademocratic terms, in part out of principle and in part to exclude Marshal Pilsudski from the presidency. This circumstance made first for parliamentary incoherence and led later to the marshal’s 1926 coup to create a strong executive—in effect, a muscular anticipation of Gaullism.

The Pilsudski government, moreover, justifiably doubtful of its Western allies’ resolve, concentrated on trying to make Poland a power capable of “going it alone” in Europe, to the neglect of its considerable internal problems. The greatest of these perhaps was that of the national minorities; for only two-thirds of the population was Polish, with the remainder made up of Ukrainians, Jews, Bielorussians, and Germans. And the Poles, in the classic manner of a victim become victor, were not much inclined to recognize for others the rights they had long demanded for themselves. Nor as a practical matter could they do so easily without imperiling the territorial integrity of their still fragile state. The result was a mixed policy of assimilation and discrimination, and of mounting ethnic tensions.

In the process parliamentarianism was subordinated first to Pilsudski’s assumption of strong powers in 1926 and then, after he died in 1935, to an oligarchy of colonels, who fell back on the army as a means of forging national unity. Nonetheless, political parties, unions, and free expression were not curtailed; and Polish society remained vigorously pluralistic, with a rich cultural life. It is thus ridiculous for some writers to describe Poland between the wars as “fascist.” The country clearly retained the moral resources to confront the wartime occupation in a democratic spirit, when leadership passed from the colonels to the London government in exile of General Wladyslaw Sikorski and to the underground Home Army, which was divided into the classic political parties.

5.

Poland’s interwar record raises still another vexing question, that of Polish anti-Semitism, or more broadly of Polish-Jewish relations. This was no ordinary episode in the history of the Diaspora; it was the central case for modern history. Four-fifths of all Jews in the world today descend from the inhabitants of the old Polish republic; and as late as the 1880s, when mass migration began to America, four-fifths of all Jews lived in its partitioned lands. In 1939 there were more than 3 million Jews in the Second Republic, a group then approximated in size only by the Jewish community of the United States and a third larger than that of the Soviet Union. Professor Mendelsohn’s closely researched monograph Zionism in Poland, read in conjunction with Professor Davies’s broader observations, provides a good perspective on their condition.

At the end of old republic the Jews numbered 10 percent of the population, and they were there for two good reasons: first, they had been legally expelled from, or hounded out of, most of Western Europe; and second, the republic’s multi-confessional structures made it possible to give them sanctuary. They thus came to constitute a separate estate, with its own elected administration, culture, and language. To be sure, their lot was not without its perils, for their economic association with the szlachta generated popular hostility, and in the Cossack revolts of the Ukraine led to devastating massacres. Still, the republic’s Jews felt that they were far better off in Poland than they would be anywhere else. Indeed, they increased and multiplied to become the heart of world Jewry by the republic’s demise.

The partitions were as great a disaster for the Jews as for the Poles, at least in those provinces that fell to Russia. Until then there had been no Jews in Russia, and the czars treated their new subjects as some dangerous infection which they confined by law to a Pale of Settlement in the empire’s western borderlands. It was in this situation that, after the Russian government introduced the May Laws of 1882, state-sponsored discrimination produced an era of officially encouraged pograms that mark the beginning of modern, political anti-Semitism—and in answer to it, the exodus to America and the rise both of Jewish radicalism and of Zionism.

And what of the restored Polish republic, where again the Jews comprised 10 percent of the population? With such a figure, a threshold of intolerance for minorities in most other countries, it should hardly be surprising that there was much vociferous anti-Semitism in Poland, a phenomenon aggravated by the heady Wilsonian breakthrough to ethnic self-determination throughout Central Europe. The real question, rather, is the degree of such xenophobia, its practical consequences, and the level of opposition to it. In this connection it may be recalled that Polish nationalism was not a monolith, but divided between the open tradition of the old republic and the insurrections and the recent closed ethnocentrism of the Endecja—or, to simplify, the ever warring camps of Pilsudski and Dmowski.

Although the ethnocentric Endecja never came to power, by the second half of the 1930s its growing influence produced “ghetto benches” in the universities and sporadic boycotts of Jewish businesses. At the same time, rapid demographic growth in conjunction with great poverty among the unassimilated, Yiddish-speaking masses induced a mood of demoralization and helplessness that ill prepared them for the cataclysm of 1939. Still, the Pilsudskiites and the left did not stop opposing the Endecja, and Jewish political and cultural activity, whether Orthodox, Bundist-Socialist, or various kinds of Zionist, continued unabated along with assimilation. Even the colonels sponsored the paramilitary units of the young Revisionist Zionist, Menachem Begin, to prepare for the conquest of Palestine—in order to get rid of him and his fellows, to be sure, but also on terms they could accept.

Indeed, the Polish Romantic-heroic ideal of patriotism to some degree furnished a model to Polish Zionists of all persuasions; for they, too, had been raised on Mickiewicz’s national epic, Pan Tadeusz, where Jankiel the Jewish minstrel sings the most patriotic and libertarian lines of the poem. It is perhaps not an accident that many of Israel’s most prominent leaders since David Ben-Gurion, a Paole Zion revolutionary of 1905, were born in Poland. Numerous aspects of the Jewish condition were oppressive and odious under the Second Republic; but they in no sense prefigured or prepared for the Holocaust (as some writers, for understandable but misguided reasons, have at times asserted). Then, in 1939, real catastrophe struck: Nazi conquest virtually annihilated Polish Jewry, thereby ending half a millennium during which Poland had been Europe’s most important Jewish refuge.

If for the Jews World War II meant the Holocaust, for the Poles, in another religious image, it was Golgotha. In September 1939, Poland experienced the combined onslaught of Europe’s two totalitarian empires, and the nation was again extinguished in a fifth partition between them. A million and a half Poles were deported to Soviet camps and, by the time the Germans were through, 6 million Polish citizens, half of them Jewish, had perished at home. The remaining population, though not slated by Hitler for extermination like the Jews, was to be shorn of all its leaders and reduced to a herd of menials. The country was devastated materially, before its remnants were picked up and its borders moved 150 miles west by Stalin at the war’s end.

Nonetheless, the Poles organized the largest resistance movement in Europe, again creating an underground army and state. They fought with conspicuous valor for their Western allies in Norway, Italy, and Normandy—indeed even for Stalin. And they produced no Quisling or collaborators. Yet it turned out that they did all this in vain.

After 1941 their ostensible Eastern ally, Russia, remained in fact a covert enemy, and their Western allies, while Hitler was still in the field, needed Stalin too much to challenge him over Poland. So the Poles wound up, de facto, in a surrealistically familiar war on two fronts, which culminated in the foredoomed yet psychologically inevitable Warsaw Insurrection of August 1944—an uprising directly against the Germans and preemptively against the Soviets. The result was a disaster for the resistance Home Army that cleared the way for the puppets of Stalin’s Lublin “government.” A few months later, at Yalta, Roosevelt and Churchill, though insisting on nominal concessions from Stalin, in fact acquiesced in this outcome and abandoned Poland to its Soviet fate.

This drama is recounted in Jan Nowak’s memoirs, a recent samizdat best seller in Poland. A daring courier between Warsaw and London during the occupation, Nowak conveys in low-keyed fashion the yawning gap between Polish and Allied perceptions of the war. He then draws the moral that the Warsaw Insurrection, for all its practical futility, was nonetheless the sacrificial guarantee that Poland would never accept the verdict of Yalta. Indeed, to this day for the Poles there is no such thing as the “victory” of 1945. The struggle that began in 1939 still goes on, and will continue in covert form until the second, Soviet invader of that year is somehow dislodged and the true republic restored—just as after 1795 their ancestors could not rest until the crime of the original Rzeczpospolita’s extinction had been expiated.

6.

After 1945, therefore, the old struggle to preserve the nation resumed under daunting new Soviet socialist conditions. For communist totalitarianism, unlike the blatant brutality of Nazism, surreptitiously pulverizes an occupied society by subordinating its atomized population to the Party apparatus. And it is all the more corrosive in that it does this in the name of a “radiant future” of socialism. Thus after 1945 a good part of the prewar Polish left, including much of the Socialist Party, was drawn into collaboration with Stalinism to form the United Polish Workers Party. Even though many of the people involved later broke the shackles of the “captive mind” (in Czeslaw Milosz’s phrase), classical leftism was significantly compromised in Poland. So the moral leadership of the nation fell to the Church.

The Polish Church, of course, had been since the partitions a bulwark of the nation. But it was a conservative Church, clinging to the past and to tradition against threatening secular forces in order to preserve the people’s faith. Under the Second Republic, alarmed by godless Russia next door and by radicalism at home, it became more ingrown still and inclined to a strict construction of the old tenet “polak-katolik.” But the horrors of the occupation, then of Stalinism, jolted it into a new life. The decimated, persecuted clergy opened up to imaginative intellectual and social currents from the West, especially France and Belgium, such as the personalism of the review Esprit and the transcendental Thomism of Louvain. George Williams, in his study of John Paul II, traces this remarkable renaissance of Polish Catholicism.

The great architect of the renaissance was the primate Stefan Cardinal Wyszynski, who while an ordinary priest had served as a chaplain during the Warsaw Insurrection, and who, when interned by the Stalinist authorities in the early 1950s, became a Marian mystic. As Stalinist control weakened, he rebuilt the spiritual and national consciousness of a demoralized people through an extraordinary combination of traditional and modern means.

On his release from prison in 1956, he renewed the vow of King Jan Kazimierz exactly three centuries earlier—for had not the years 1939-1956 been an even greater Deluge?—by reconsecrating the nation to Mary as queen of Poland. He then organized a nine-year “Great Novena,” each year with a special theme of meditation on Poland’s values and its sins, during which replicas of the Black Madonna of Czestochowa visited every parish in the country. The novena built up to a celebration, in 1966, of the millennium of Poland’s conversion. Through all of this he was proclaiming that the true Poland lived by Christianity, not Marxism. By the fateful anniversary he had won: vast numbers of workers and peasants stood solidly with their queen and ignored the regime’s competing celebration of the thousand years of Polish statehood.

At the same time, in a more modern vein, Wyszynski fostered lay clubs of the Catholic intelligentsia (the KIK), their various independent-minded publications, such as Kraków’s Znak, and the Catholic University of Lublin which trained professors for seminaries. From such institutions there emerged a dynamic “conciliar” laity and a highly educated younger clergy, including of course Karol Wojtyla. Through this effort, moreover, the Church spoke with ever greater insistence of absolute and universal moral values, of innate human rights founded on natural law, of social justice and the dignity of labor, of the inviolability of individual conscience and society’s right to the truth; and above all of faith in God’s incarnation in Christ as the foundation of genuine “humanism,” since it brings the true sanctification of man—in sum, the basic themes of John Paul’s sermons on his two visits home.

This exaltation of the “human personality” as an end in itself and as the governing principle of social organization was all the more potent in that Marxism utterly lacks a theory of ethics. For it holds that all “so-called” absolutes as “justice” and “human rights” are a mere “superstructure” on material interests, simply the “universal brotherhood swindle” of the bourgeoisie, and that right and wrong are wholly relative to the class struggle—in practice, under Leninism, to the will of the Party. The outcome of this ideological confrontation was that by the 1970s, with the regime’s growing moral bankruptcy, the Church had become the principal heir to the humanism of the old left, as the historian Adam Michnik, a professed “pagan,” warmly recognized in the name of KOR in his major book, The Church and the Left: A Dialogue.3

It is against this background and with these values that the Polish political revival, cut short in 1944, resumed after 1956. The continuity of this revival is examined in Jakub Karpinski’s Countdown, which makes clear that the series of now familiar postwar crises, too often considered as separate episodes, are in fact stages in a single process of rebirth.

In 1956 the slaughter of protesting workers in Poznan returned the “national” communist Wladyslaw Gomulka to power and ended Stalinism. In 1968 this pseudoliberal regime, alarmed by the Prague Spring, exploited the residues of Endecja anti-Semitism within the Party to purge “revisionist” intellectuals, thus eliminating serious ideological Marxism. In 1970 the striking shipyard workers of Gdansk and Gdynia were crushed in a massacre; this shock toppled Gomulka in favor of the more flexible Edward Gierek and, what is much more important, destroyed the myth of the workers’ state and all hope for reform from within the Party. In 1976 new strikes at Ursus and Radom led to the first alliance of workers and intellectuals in the form of KOR (Committee for Workers’ Defense) and forced Gierek to give way to their demands.

Then, in 1980, in the wake of John Paul II’s first, joyous, and liberating pilgrimage home, the entire postwar heritage came together to produce the “miraculous” August breakthrough of a national strike leading to the Gdansk accords and the birth of Solidarity. It suddenly became apparent to many Poles that the litany of often bloodstained and now sacred dates—1956, 1968, 1970, 1976, 1980—was the second, nonviolent cycle of the primal epic of 1794, 1830, 1846-1848, 1863, 1905.

Abraham Brumberg’s fine selection of key documents and articles by leading Polish émigrés appositely relates the struggles of the second cycle to the legacy of the first. Alain Touraine’s investigation of Solidarity activists, the best study to date of the union itself, presents a similar picture in a social science idiom. For his conclusion, based on interviews by a Franco-Polish team of labor sociologists, is that, under the “totalitarian” conditions of a party-state, a normal workers’ movement inevitably expands into broader social, national, and ethical-religious protests, all amalgamated as a “total social movement.”

By now, however, it should hardly be necessary to insist that Solidarity is no mere trade union but indeed the eternal return of a total national idea that, against all odds, refuses to be stifled. It is remarkable how little the historic Polish pattern has been changed by the postwar revolution of socialism. Yet this revolution was, in truth, immense. The old social structure of Poland was leveled; and a majority of the traditionalistic peasantry was transplanted to new industrial cities and placed under the suffocating rule of Party bureaucrats. For some time, however, these raw recruits to urban life accepted the regime’s terms; and as late as the strikes of 1970 their song of protest was still the “Internationale.” But by the start of 1980 a second, more educated generation of workers was ready to stand on its own, and it would sing only the March Dabrowski of 1798 and the “God Restore Free Poland” of 1863.

Indeed, it is not too much to say that this young working class, in its mentality at least, resembles nothing more than a gigantic plebeian szlachta, insisting on the principle of “nothing about us without us” and aspiring to the “golden freedom” of its ancestral lords. And at Solidarity’s only national congress, in September 1981, comparisons could even be heard with the Great Diet of 1788 and its Constitution of May 3.

7.

But where do matters stand at present, and what of the future? The Polish “crisis” that began in 1980 is now three years old, the greatest show of defiance ever to take place in the Soviet empire. Yet “normalization,” as communism conceives it, is nowhere in sight. Instead, the outcome is a standoff, in a muted form of “dual power,” between a stubbornly renascent civil society and a decomposed party-state reduced to acting as an unabashed junta. All this is unheard of in the annals of Leninism, and as such is a historical watershed. The details of this resistance are explored in Poland Under Jaruzelski, an excellent collection of important documents and commentaries.

To be sure, after eighteen months of a “state of war,” the regime in June felt it had recovered enough to permit a papal visit, but at the unanticipated cost of dramatizing the nullity of its recovery. In another would-be display of normality, in July the regime cast off its embarrassing uniform by “lifting” martial law and returning the country to nominal Party rule. But this gesture, too, revealed as much weakness as strength, for the government had simultaneously to promulgate a “state of crisis” with civil measures so draconian as to give Poland its most iron order since Stalinism.

Still, the regime has achieved one essential purpose: it has at last made clear that it is bent on full normalization and that the population should abandon all “illusions,” until now recurrent, that it would have to accept a “dialogue” and a compromise with society. For was not the “enigmatic” Jaruzelski, so the argument ran, a “moderate” within the Party (and there are indeed worse than he), perhaps even a closet patriot, shielding Poland from the full fury of Moscow? But the July legislation makes it unmistakable that the regime aims to crush all vestiges of social autonomy, whether in the factories, professional associations, or the still self-governing universities. It thus counts on reducing the population to resignation and despair, as it did the Czechs, through a monopoly of physical force and in the belief that time is on its side; for this is what the “fraternal countries” demand.

Nevertheless, the restored party-state is hollowed out by the omnipresent memory of Solidarity. For the union was much more than an organization; it was a movement of ethical conviction and a force of conscience. This force is as alive as ever, as John Paul II deliberately dramatized by provoking an outpouring of Solidarity “fidelity” among eight million Poles massed along his second, somber pilgrimage route.

So long as this force still lives, the restoration of the mixture of fear, corruption, pretense, and hopelessness that makes a party-state function “normally” is impossible. Indeed, the population refuses to join the new official unions in any numbers, or to enter at all the regime’s front and would-be substitute for Solidarity, the Patriotic Movement for National Salvation (PRON). Thus the Party cannot re-create its “normal” modes of controlling the lower orders.

For the grass roots of Polish life continue to be occupied by a clandestine Solidarity operating in all factories, not exactly an underground state in the old manner but a genuine underground society. This network turns out several hundred newspapers, magazines, and factory bulletins monthly. Some two thousand or three thousand Solidarity factory committees regularly collect union dues and pay support to the sick, fired workers, and families of political prisoners.

All the same, Solidarity cannot win, since it has no means of forcing the regime’s hand. So the standoff will continue…indefinitely. Yet John Paul II’s visit provides a good key to its future shape. On the one hand, in a militant mode, he summoned the people “to call good and evil by its name”; and he endorsed all Solidarity’s principles and the Gdansk accords as “innate civil rights” on which there could be no compromise, thus giving the clergy its instructions—to stand by Solidarity—over the head of the cautious and unpopular primate Józef Glemp (who fears above all a repetition of 1944 or 1863). On the other hand, in a more prudent vein, the pope urged the patience of nonviolence and a return to the long haul of “organic work,” a message conveyed symbolically by the beatification of two rebels of 1863 (read also: 1980) who later entered religious orders and labored on as educators.

But organic work is not a passive program. In present circumstances it means national renewal through faith; and surveys indicate that Polish churches have never been so full as at present, with weekly attendance up from a usual 65 percent to an astounding 90 or 95 percent. It means also the unremitting pressure of society’s “fidelity” to Gdansk so as to bend an unavoidable regime to the real nation, in the conviction that even a party-state ultimately needs some cooperation from its menials. It could mean, finally, institutional programs, such as Glemp’s project (still not approved by the government) for a farmers’ bank, to be funded by Western churches, so as to revive Polish agriculture—though here the danger exists of cooptation by the state.4

All this, moreover, is compatible with keeping up pressure on the regime from clandestine Solidarity, or even through prudent public activism. Indeed, on August 31, the third anniversary of the Gdansk accords, Walesa, in the heavily guarded port city, was still able to make a symbolic gesture of fidelity to the union by placing wreaths at the foot of the famous Gdansk monument and giving a speech nearby. At the same time, in response to a radio appeal from the underground’s Temporary Coordinating Commission, several thousand workers demonstrated vigorously in the streets of Nowa Huta and Warsaw in defiance of the government’s orders; and at the end of the working day many Poles took part in a boycott of public transportation that had high visibility and low risk. And all past precedents make it certain that both the union and the Church will challenge, in some fashion, the impending trials of seven Solidarity leaders and five KOR activists.

All very admirable, no doubt, the skeptic will say, but what practical good can it do? Indeed most Poles are now aware, as they were not in 1980 and 1981, that there is no way out of their dilemma within Poland alone, but that the Soviet empire itself must somehow be moved. For John Paul II, who like Wyszynski is a Marian and millenarian mystic, as well as sensitive to Orthodoxy and the common ties of Slavdom, this means reanimating the other churches of Eastern Europe so as to force concessions to the popular will from a morally moribund communism. This is why he has, for the first time, named cardinals in Soviet Lithuania and Latvia, and why he brought along most East European primates to Poland in June. For most Poles this means simply “keeping the faith” as best they can until something cracks elsewhere in the Soviet bloc, or within the gerontocracy of Moscow itself. Chancy wagers at best.

So why don’t the “foolish” Romantic Poles, these eternal losers, just give up and leave the world to its more pressing crises? But the Poles have gone too far since 1980 to turn back now and submit to the lie of normalization, thereby abdicating their hard-won “human personality.” And lofty Westerners, who come by their rights without effort, fail to see that the Poles at present are not playing to win, but only not to lose absolutely; for in their straits this is itself a “victory.” Nor should we forget that the record of two great cycles of resistance demonstrates their awesome capacity for coexisting with the impossible indefinitely: until some new “miracle” of Czestochowa, of the Vistula, or of Gdansk turns up.

—August, 31, 1983

This Issue

September 29, 1983

-

1

See Daniel Singer, The Road to Gdansk (Monthly Review, 1981 and 1982) and in much more sophisticated fashion Neal Ascherson, The Polish August (Viking, 1982). ↩

-

2

This political union was supplemented by a less successful religious union at Brest in 1596, between Catholics and Orthodox, which in fact split the duchy between a majority of Eastern-rite Uniates under Rome and a minority of Orthodox, thus weakening it vis-à-vis Moscow. ↩

-

3

See Abraham Brumberg’s review, “The Open Political Struggle in Poland,” The New York Review, February 8, 1979, pp. 31-33. ↩

-

4

For the papal visit see especially Bernard Guetta, Le Monde, June 1983, passim, and Timothy Garton Ash, The New Republic, July 18, 1983. For underground Solidarity see Reports, regularly issued by the committee in Support of Solidarity, NY, and Poland Watch, Washington, DC. ↩