Both these novels by established writers are about people undergoing crises of conscience in circumstances of modern political and social turmoil. Young Cal Mc Crystal, the unemployed Belfast laborer of Cal, has done driving jobs for IRA hit men and feels directly implicated in the murder of a Protestant farmer named Morton at his own house door and in the grievous wounding of Morton’s elderly father. He wants to get free of the violent men and somehow make a proper acknowledgment and full expiation of his guilt, but his problem becomes much more perplexing when, through a fairly believable concatenation of events, he finds work at the Morton farm and falls painfully in love with the murdered man’s widow, the Roman Catholic Marcella.

The irony puts us in mind of the Russian student Razumov in Conrad’s Under Western Eyes. After betraying his fellow student, Victor Haldin, to the czarist police, Razumov was forced by the Russian authorities to spy on revolutionary circles in Geneva. There he met and fell tormentedly in love with Haldin’s sister. Cal is quiet and small, not given to the moody acting out, including fits of manic laughter, of the Russian. Yet they are brothers just the same and are cut to the same or a similar thematic pattern. In a formula, the crisis of modern politics and society, broadly speaking, creates the crisis of conscience each character must work through, but provides no clues to the work of expiation each must perform if he is to find his way back to the human community. These woefully isolated and lonely characters come under added pressure as ironies of circumstance bring them into intimacy with the trustful relatives of their victims. For a brief time Cal actually becomes physically the lover of Marcella. Not unexpectedly, their lovemaking, from the boy’s conscience-stricken standpoint, is a painful joy.

The mark of Under Western Eyes is on The Summoning too, if only in the apparitional reappearance of a long-deceased victim to summon a character to begin the effort of moral recognition and repentance. But despite the plot ingenuities and many studied effects of this book, it is somewhat inferior to Cal in moral seriousness. Mr. Towers’s main problem is with his hero, Larry Hux, a divorced foundation executive of North Carolina origin, living—I should say wallowing—in unkempt bachelor quarters on the Upper East Side as the story gets under way in 1974. One simply does not believe Hux has enough common sense and decency to endure the ordeals and attain the recognitions laid out for him by the plot. Indeed, at the risk of sounding prim, I would guess that most, perhaps all of this character’s life crises would melt away like mist if he stopped getting drunk, cut back on casual sex, stopped gluttonous consumption of unappetizing food, and took exercise. This reform might not make him decent but at least it would quiet him down.

Hux is thirty-seven when the story begins. Ten years earlier, while still a graduate student at Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public Affairs, he had taken part, along with his brilliant fellow student, Clark Helmholtz, in the now historic Freedom Summer in northern Mississippi. Called home early by his young wife, who was having trouble managing a new baby on her own, Hux had not been present when a sniper bullet, fired by a white doctor named Claiborne Herne, ended Clark’s life as he addressed a crowd in Tupelo, Mississippi. Dr. Herne was indicted for the murder but got off. He now lives quietly in retirement with his seventy-year-old sister, Isabelle.

The events of 1964 have dimmed in Hux’s mind when an apparition of Helmholtz, with bullet-smashed head, appears in his frowsy apartment. Guilt and concern revive and Hux goes south, determined to summon the segregationist physician to repentance, if not actually to slay him in revenge for his friend’s death. In order to penetrate the Herne household at Alhambra, Mississippi, and win the confidence of Miss Isabelle, Hux finds it convenient to adopt the persona of a fundamentalist preacher, “the Reverend Ainsley Black.” This transformation is not altogether believable, unless we assume that every Southern child raised Baptist or Methodist contains a Bible-thumper ready to come thundering forth as needed.

As Hux begins to gain influence over the Hernes he discovers that his preacher identity is taking him over. Is he, however, doing the work of the devil or God’s? He starts an affair with a local divorcee of liberal outlook who turns out to have been the dead Clark’s mistress during that fateful summer. But this dalliance does not prevent him from suffering a nervous collapse with religious overtones, from being badly beaten by the black gangster Rooney, who exercises baleful influence over Doc Herne, and from harrying and annoying the alcoholic old man with calls for confession and repentance, to the point where the doctor actually commits suicide. Filled with remorse, Hux suddenly remembers a fight of his own with Clark just before he went north to help his wife with the baby. Clark had jeered that his wife dominated him—only using cruder language—and Hux had come within seconds of throttling his friend to death in the brawl that followed. It has come out that Claiborne Herne actually fired at a black activist on the platform at Tupelo, hitting Helmholtz by mistake. So Hux is perhaps more guilty of wanting Clark Helmholtz to die than the doctor was.

Advertisement

This long-delayed but somehow predictable moral revelation is undermined by the detail of Hux’s having completely forgotten about the fight during the intervening ten years. Do grown people, outside books, forget such things? I am not at all sure that they do.

Certainly The Summoning has some good things: the comedy and pathos of the Herne siblings’ domestic round; an undress portrait of a genuine revivalist preacher named Archie Thurlow; a mordant low-life episode in a Memphis massage parlor, and a grim but effective scene between Hux and his neurotic, unloving mother when he makes a quick visit to North Carolina. It’s just that it’s very hard to accept Hux as a figure of conscience and certainly it isn’t easy in 1984 to become absorbed in the situation of a character in 1974 who is attempting to assess responsibility, including his own, for tragedy occurring a decade earlier.

By contrast, Cal urgently addresses the Northern Irish problem right now. Its virtues as fiction include an elegant economy of form and authenticity of detail. When young Mc Crystal turns on the TV he hears “the calm voice of the news reader giving the headlines of the day’s events. Two hooded bodies had been found on the outskirts of Belfast; bombs had gone off in Strabane and Derry and Newry but no one had been hurt; there was another rise in coal prices; and finally there was the elephant in Belle Vue Zoo that had to have his teeth filed.” That is exactly the way the news is given in Belfast, usually by young women whose voices are not only calm but dulcet-toned and with the faintest suggestion of a Scottish inflection.

Cal lives alone with his widower father, Shamie, a slaughterhouse employee, in a housing estate where all the other families are Protestant. The sad constraint of their daily relations is beautifully drawn. After the Mc Crystals endure threats and beatings the house is burned by young Unionist punks and the father has to shelter elsewhere with kin who have little room for him, and he disintegrates, sliding into a severe depression. For a while Cal makes do as a squatter in a disused cottage on the Morton farmstead, until one night a British army patrol bursts in, routinely bloodying him before they even bother to ask questions.

Cal’s cult-like love for Marcella, the young widow of the murdered farmer, builds slowly, from the time he first notices her working at the local public library, through seemingly casual encounters around the Morton place, to the night they become lovers. Mr. Mac Laverty has the gift of a genuine novelist—or is it craft, after all?—of absorbing particular details into a flow of narrative that overwhelms and defeats a reader’s disbelief.

Occasionally the writing becomes fussy; it takes six lines in a very short book to describe sticking a band-aid over a cut. The author makes discreet use of allusion, some of it enriching, some of it merely overloading his narrative. There is a useful irony in his naming his gentle, dreamy, even pacifistic title character Cahal. The popularity of this name in Ireland is traceable to Cahal Burgha, the famous Sinn Fein irreconcilable, who died in a gun battle with Free State soldiers in the Irish Civil War, only to be resurrected as an Irish national hero just as soon as he was safely interred. But the attempt to establish Morton’s widow, Marcella, as a Madonna figure—by making her not only Catholic but also of Italian ancestry and on visiting terms with Roman relatives—is overdone.

Marcella’s Madonna-like character is part of a larger theme in Cal that I find disturbing: the theme of masochistic suffering seen as a substitute for a political solution to the problem of northeastern Ireland and partition. The theme appears early, when a priest gives a sermon about Matt Talbot, a saintly Dublin ex-boozer who heaped his body with chains until they became one with his mortified flesh. “Which of us,” he asks, “would be willing to endure so much pain to right a wrong?” Just how endurance of pain to the point of mortified flesh—a not unheard-of experience in Ulster prisons and interrogation centers—can right wrongs in the real world of bombs, torture, and power politics, as distinct from the mystic world of saints and martyrs, is left up in the air.

Advertisement

Later, however, Cal reflects that every day in his part of Ireland people were suffering and dying for something that didn’t exist, for “an Ireland which never was and never would be.” So it is suggested that one must not look forward to any change in the present impasse, or take any positive line of action, but rather embrace suffering as a gift, “just offer it up,” in the homely Catholic phrase and conception of his dead mother. Cal, though, is unsure of God’s existence, but what does it matter?

…it came to him that the gift of suffering might work without Him. To offer it not up but for someone…. And that person might never know, that was the beauty of it. That way it was even more selfless.

Mac Laverty leaves little doubt that he himself believes it is noble to “embrace suffering selflessly,” that the victim should be encouraged to blame himself for what has been inflicted on him. This is not far from blaming the victim for the crime. The point isn’t quite that “conscience doth make cowards of us all.” Rather, it’s that every form of conduct, including Cal’s love-struck, guilt-ridden, newly acquired, quasi-religious quietism, has to run into the buzz saw of politics in the crisis of Northern Ireland.

That point is not made sufficiently clear in the ending when Cal meets with his former IRA associates and tells them he wants out. They tell him he must stay in or else face liquidation as a potential informer to the police. While this deadly debate is in progress the police do break in. The IRA heavies—scorpion-like Skeffington and the murderous bully, Crilly—are taken into custody immediately, while Cal, who briefly escapes to enjoy one last night with Marcella, is taken the next day (Christmas Eve) at his laborer’s cottage on the Morton farm. Wearing the garments of her murdered husband, the man in whose death he is implicated as the driver of the getaway car, he stands “listening to the charge, grateful that at last someone was going to beat him to within an inch of his life.”

Never mind that nobody is ever grateful for such a beating, these final phrases of the novel have the power to move us. But what is actually going to happen to Cal now that he is in custody, with his crime and criminal associations presumably known? Will the savage if routine police beatings expiate and cancel his guilt and guilty feelings, enabling him to start a new life after a prison sentence?

That seems very unlikely. Either he will be denounced as an informer by his now vengeful IRA connections and killed in jail; or else some psychological genius in the security apparatus, working on his tender conscience, will recruit him into Northern Ireland’s new and grotesque “supergrass” program of highly compensated if poorly protected police informers. In the latter event, it may be several months or even a year or two before Cal’s disfigured corpse comes to light in some ditch or boggy spot along the Monaghan or Fermanagh border between the Republic and the six counties. How either of these outcomes confirms the value of embracing suffering selflessly is far from clear.

Cal Mc Crystal is a doomed man. Death is the only going wage for someone of tender conscience and an individual standard of conduct who has the misfortune to be caught in the Northern Irish partisan struggle or political meat grinder at this time. That is the truth the talented Bernard Mac Laverty, living and writing his parables of conscience about Ireland on a quiet island in the Hebrides, slides away from in his closing descriptions of the passionate couplings of Marcella and Cal, and Cal’s grateful anticipation of a bad but not fatal beating at the hands of authority.

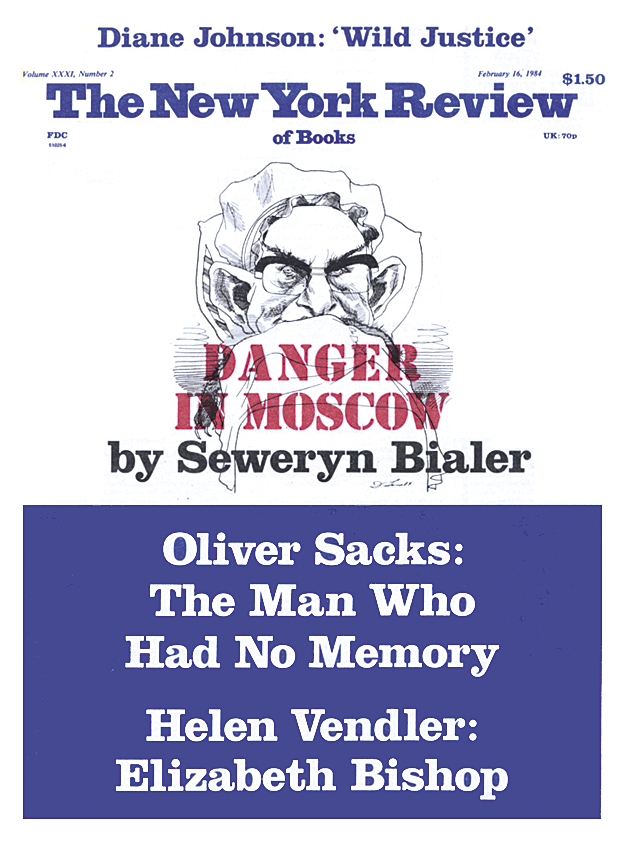

This Issue

February 16, 1984