“All the governments, including that of Russia, and the great majority of the peoples are pacific, but things are out of control [es ist die Direktion verloren],” the German chancellor remarked gloomily at the height of the crisis leading to the outbreak of World War I. And other politicians with a share in the decisions that brought their countries into the war had similar feelings. “The nations slithered over the brink into the boiling cauldron of war without any trace of apprehension or dismay,” Lloyd George later observed, and S.D. Sazonov, the Russian foreign minister, admitted to being “débordé par les événements.” This is an understandable attitude for politicians to take, especially in retrospect when they can see that the war they started turned out to be a very different kind of war from the one they expected.

Historians, however, are reluctant to accept that the war was the result of some general fatality and want to find more specific causes for it. Their interpretation varies with their own contemporary preoccupations. Immediately after the First World War the Allied governments wanted to justify their demands for reparations and to satisfy the popular desire for vengeance by asserting Germany’s “war guilt.” In reaction the German historians set out to prove Germany’s innocence and to spread the blame more widely. Liberal historians, following Woodrow Wilson’s insistence on “open covenants openly arrived at,” accused the international system and the “old diplomacy”—an explanation which has the advantage that if everyone is to blame, it comes to much the same thing as saying that nobody is.

World War II seemed to confirm, at least for British and American historians, the belief that, as Germany was responsible for the Second World War, so it must have been responsible for the first as well, and this view was given fresh support in the 1960s by evidence produced from the German archives by Professor Fritz Fischer which suggested, to the indignation of German conservatives, that there was some continuity between Germany’s aims in the First World War and Hitler’s aims in the Second.

More important, however, was the suggestion in Fischer’s work—eagerly taken up by those historians who were challenging the accepted view of the origins of the cold war between the US and the USSR—that the war, and, by implication, all wars, were the result of domestic pressures from economic interest groups and of governments’ need to distract attention from internal political and social problems by creating a national patriotic consensus. The belief that foreign policy was determined by internal politics was now asserted against the traditional view held by Ranke and other nineteenth-century historians that it was foreign policy which determined the domestic development of states. A belief in the Primat der Aussenpolitik gave way to an emphasis on the Primat der Innenpolitik.

At the same time some features of the international scene before 1914—the arms race, the instability caused by the national aspirations of small states, for example—seemed disconcertingly like the situation today. Already in 1965 Jonathan Steinberg called his pioneering study of German naval policy Yesterday’s Deterrent; and in a skillfully written article published in Foreign Affairs in 1979 Miles Kahler argued that the crisis of 1914 still had lessons for contemporary statesmen, such as the danger of conducting international conflicts by proxy or the mistake of believing that because one crisis had been resolved without war, as in 1911, the next one would also have a peaceful solution.1

D.C.B. Lieven in his interesting and original study of Russia and the origins of the First World War (marred slightly by an unduly high rate of typographical errors and the absence of accents on foreign names) combines two approaches. “Russia entered the First World War,” he writes, “because mankind had not devised a method whereby conflicts between sovereign states could be resolved by peaceful means.” More precisely, however, he shows that Russian policy was the result of the structure of the czarist governmental system and the pressure of internal political factors. At the same time he believes that the war was the result of the failure of a policy of deterrence:

Deterrence and the balance of power on which most Russian statesmen had pinned their hopes for peace, did not stop Europe from sliding into war, though they might have done so had the power of the European rival blocs actually been balanced and had the British commitment to deterrence been unequivocal.

This is not quite true as far as Britain is concerned, even though there were people in England who by 1914 were beginning to wonder whether Russia might not be about to pose as great a threat to the balance of power as Germany. In fact the German General Staff had for several years reckoned that their plan for invading Belgium in order to defeat the French would lead to British intervention but that the British military contribution would not be big or rapid enough to prevent a speedy German victory over France.

Advertisement

Lieven’s book (and he is the first person to give us this perspective) tells us how the Russians viewed deterrence, but it also demonstrates the difficulties of following a policy of deterrence in an international system in which there are more than two great powers. Deterrence is perhaps a credible policy for a country that feels itself in danger of attack; and certainly by 1914 there was much talk both in Germany and Russia of the inevitability of the forthcoming conflict between Teuton and Slav, so that each country believed, or said it did, that it was threatened by the other.

However, the Russians had their own territorial ambitions for which they were prepared to risk a war. These ambitions were both positive—the desire to control Constantinople and the exit from the Black Sea—and negative—to prevent the spread of Austrian influence in the Balkans, notably Serbia. If, as happened after the first Balkan war in 1912, Turkey finally lost control of her remaining provinces in Europe, then, as the Russian former Foreign Minister Izvolsky put it, it would be

most fraught with threatening consequences for the general peace; it would bring forward, in its full historical development, the question of the struggle of Slavdom not only with Islam but also with Germanism. In this event one can scarcely set one’s hopes on any palliative measures and must prepare for a great and decisive general European war.

The Russian government felt that at any cost Constantinople must be prevented from falling into the hands of any other power. There were strong suspicions of Germany’s expansionist ambitions in southeast Europe; and even if, as the Russian ambassador in London put it, “this expansionist force in no way necessarily means that the Berlin cabinet is deliberately waging an aggressive policy…it entails counter-measures on the part of the other powers which always create the danger of conflict.”

The crucial element in Russian foreign policy—which it was hoped would enable Russia to ensure her predominant influence in the Balkans—was the alliance with France. The Russians believed that the threat of a two-front war would be enough to deter Germany from interfering. But, like all alliances, the Franco-Russian alliance was often strained and the immediate interests of the two allies did not always coincide, particularly when the Russians felt that the French were not sufficiently supportive of their Balkan policies and had their eyes too firmly fixed on “the blue line of the Vosges” and the recovery of Alsace-Lorraine.

By 1912, however, the fear of Germany was consolidating the alliance, the military cooperation between the two countries tightened, and the pace of the international arms race accelerated. In 1913 the French made plans to increase the size of their army by extending the period of military service from two to three years and the Russians were projecting a 40 percent increase in their army over the next four years, while the Germans were once more expanding both their land and their sea forces. In September 1912, the French prime minister, Raymond Poincaré, shortly to be elected President of the Republic, assured the Russian ambassador that if a Balkan crisis led to war between Russia and Germany and Austria “the French government recognizes this in advance as a casus foederis and will not waver for one moment to fulfill the obligations lying upon it with respect to Russia.” The chances of localizing a conflict in the Balkans were diminishing rapidly.

John F.V. Keiger, in France and the Origins of the First World War, is primarily concerned to defend Poincaré’s reputation and to show that he was consistently trying, as Poincaré himself claimed, to “induce our ally to exercise moderation in matters in which we are much less concerned than herself.” Some historians have questioned this, feeling that Poincaré could have done more both before and during the crisis of July 1914 to restrain Russian ambitions, moderate its unlimited backing for Serbia, and delay Russian mobilization. It certainly seems true that by 1914 both allies were primarily concerned to make the alliance as strong as possible. The question remains how far each partner saw the alliance just as a means of deterring German aggression and how far as a means of obtaining its own ends: for the Russians, control of Constantinople and the Straits; for the French, and especially perhaps for President Poincaré, the recovery of Alsace and Lorraine. Even if the French and the Russians did not provoke war they certainly did not exclude it as a means of obtaining their goals. They believed that their objectives might well be worth the risk of war.

Advertisement

The discussion of the origins of the First World War has recently centered on the controversy about German policy and the extent to which the Germans deliberately provoked the conflict (a topic admirably dealt with by V.R. Berghahn in an earlier volume in the same series as Lieven’s and Keiger’s books2 ). For many years, indeed since 1914 itself, there has also been argument about whether, as Lieven seems to suggest, Britain could have done more to prevent the conflict, and on this subject Zara Steiner’s volume in this same series is already a standard work.3 It is therefore very valuable to have detailed studies of Russian and French foreign policy. Lieven is clearly rather bored by diplomatic detail and thinks the answers to his questions lie in the influences, personal, institutional, and ideological, that formed Russian policy.

Keiger, on the other hand, sees the story as mainly concerned with diplomacy. For him, the controversy over the dismissal by Poincaré of the ambassador in St. Petersburg, Georges Louis, seems as important as French strategic planning for war or the deep political divisions in French society on the eve of the war. Perhaps, though, this is how contemporaries really saw international relations. Perhaps it was the desire of historians to find more general or more profound explanations that drew attention to other factors. Men are not always motivated by a clear view of their own interests; their motives are not always clear even to themselves.

The consequences of the war turned out to be so vast that, as Luigi Albertini put it many years ago, “the disproportion between the intellectual and moral endowments [of the politicians] and the gravity of the problems which faced them, between their acts and the results thereof” seems to demand some deeper cause than just the folly, vanity, or incompetence of the individuals concerned. The volumes in the same series—which include an excellent, far-ranging study by Richard Bosworth of Italy,4 the one major European power which remained neutral in the crisis of 1914 and chose its own moment to enter the war after a period of uncertainty about which side it would support—provide the material for formulating a provisional judgment about the immediate responsibilities for the outbreak of the war.

There seems to be general agreement that the German leaders were most ready to accept the risk of a general war, though there is still argument about whether their aim was to achieve world power (Weltmacht, a term that was itself open to several interpretations) or to prevent what was perceived as encirclement by hostile powers and the danger of losing their ally Austria-Hungary if they failed to support her. There is a measure of agreement about the influence of domestic politics on the British government’s hesitations and uncertainties in the final crisis. France, even Mr. Keiger would probably agree, was ready to accept war if it came and hoped that this would lead to the recovery of its lost provinces. The Russians believed it was essential to assert Russian strength either to protect the autocracy against the threat of revolution or, more vaguely and generally, to retain Russia’s prestige as a great power. The Austrians, perhaps the most misguided of all, thought that a war against Serbia, even with the risk of a European war, would solve the monarchy’s internal problems. They made the fatal mistake of thinking that a firm promise of support from Germany would deter rather than provoke Russia.

The tragedy of political decisions lies in the fact that again and again politicians find themselves in situations in which they are constrained to act in ignorance of the consequences and without even being able to assess calmly the probable results, the profit or loss that their actions would bring. This is no doubt as true now as it was in 1914. The big difference, however, is that today nobody believes in the possibility of a swift, relatively painless victory; and it is hard to believe that a nuclear war could have any aim short of the total destruction of the enemy. This makes the talk of achieving victory both meaningless and dangerous. If there is any lesson to be learned from 1914, it is that what was intended to be a limited war for recognizable aims became so destructive a general war that even victory required the payment of an unacceptable price.

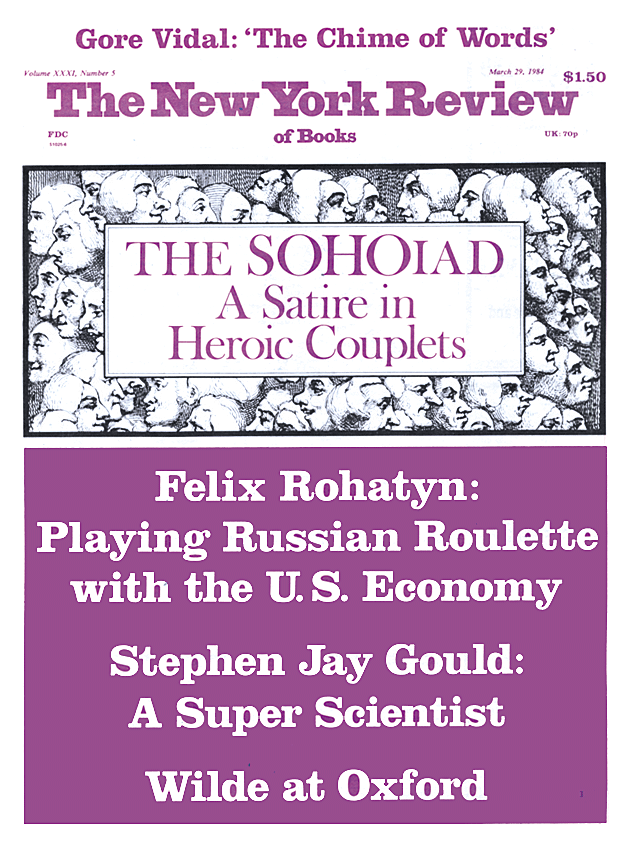

This Issue

March 29, 1984

-

1

Jonathan Steinberg, Yesterday’s Deterrent, published in the US by Macmillan, 1966; Miles Kahler, “Rumors of War: The 1914 Analogy,” Foreign Affairs, Winter 1979/80. ↩

-

2

V.R. Berghahn, Germany and the Approach of War in 1914 (St. Martin’s Press, 1973); included in The Making of the Twentieth Century series, Christopher Thorne and Geoffrey Warner, general editors. ↩

-

3

Zara S. Steiner, Britain and the Origins of the First World War (St. Martin’s Press, 1977). ↩

-

4

Richard Bosworth, Italy and the Approach of the First World War (St. Martin’s Press, 1983). ↩