The author, a physicist and poet, was sentenced in 1983 to seven years at hard labor in a Soviet prison.

On my passport the nationality column says Russian. Does that mean my homeland is Russia? Maybe, but I’d already become an adult by the time I got to geographical Russia, and even then I saw only a bit of the geography: Moscow, Leningrad, and that was all. Was I moved by the birches they sing about all the time? I have to confess, no. Those ever-rustling birches don’t grow in Odessa where I was born. The map calls it the Ukraine and my heritage would seem to be Ukrainian culture, speech, customs.

If you’ve ever been to Odessa, however, you wouldn’t be fooled: it’s not the Ukraine. I, for instance, knew all about Ukrainian speech, books, and turns of phrase, but in my twenty-four years of living in Odessa I never once had to use Ukrainian—there was no one to talk it with. Traditional Odessan speech, though related to Russian originally, gradually became infused with so many local sources, colors, and idioms that it had a unique and bawdy personality all its own. This robust creature was wholly outlawed, however. As the secretary of the Odessan City Komsomol said, only the “great tradition of revolutionary working-class struggle” could be recognized in the local language. And the spunky humor festival long held in Odessa was banished to outlying Kalinin where, neatly cut off from its sources, it neatly died. Let us remember that we are a generation that has been blessed by the blossoming of Soviet power: we have been educated in Soviet fashions by the most highly educated specialists; so we have swallowed the biggest pill of all: that our Homeland (with a capital letter) is the entire Soviet Union. From one blessed border to the other, the vast Siberian taiga and the little Baltic states are all one home, all ours. Who cares if we tore off a small chunk of Finland, or Poland, or Japan—it’s still the same dear place, one we love to distraction and would gladly lay down our lives for. The only thing is that we know no normal person can have such a sense of homeland.

What else is there? Poland? That is where my great-grandfather got himself killed for taking part in a patriotic revolution. My ancestors had large estates there, which they lost just about the time they got smart enough to survive as new creatures in Odessa. I learned a little of the old Polish world through books, and a little about Polish literature through cracks here and there in the screen of Soviet censorship. I got some glimmerings of the Polish character, too, from tirades in the work of Maxim Gorky in which a crude world, safely separated from polite society, was described, not as Gorky saw it, but through the eyes of a simple, politically illiterate gypsy woman.

But I shouldn’t forget that it was the Soviet authorities who erased all curiosity and concern for our origins that any of my family—once nobles—might ever have had about those earlier times. Times now were hard enough—and there was plenty to fear from officials snooping through our pedigree. And so we forget, and so we exchange identities: memory is not safe for Soviets. As for those quaint museum pieces—Polish, Odessan, and Ukrainian speech, and families—they are nothing, in no way connected to real life. My grandmother was devoutly Catholic; how many times did the KGB call her in because of her churchgoing? Thus was I protected. My relatives kept my grandfather and my grandmother from teaching me the Polish language; they forbade them to speak to me of their love of religion and other “non-Soviet” themes. The grandchild must not be contaminated. The old threads from the past, those useless umbilical cords, were to be dried up and cut off.

What was left? Was I to find joy in the homogenized Soviet intelligentsia? In their genteel literature? Even my dear mother, who taught literature in school, couldn’t tell the difference between Pasternak and Balmont. Of Blok she knew only the officially sanctioned poem “The Twelve.” And this was where I found myself. Only after I had learned about the “silver age” of Russian literature did I begin to hear certain ill-mannered “decadents” whose only achievements were that they were untalented and, rogues that they were, threatened to lure the people away from the true path of revolutionary struggle. This was our culture.

Try an imaginary experiment—I say “imaginary” because no normal person could ever do such a thing—and yet it happened to our entire nation. The experiment is this: take any book you have and, with a dull file, hack a large piece off of it. Now from this piece try to figure out what the contents might have been of the whole book—but first destroy the rest so you’re not ever tempted to look back. You would then have what was done for our benefit: destroying genuine culture to bring us to “the present epoch of the Soviet race.” That is how we found our destiny under communism.

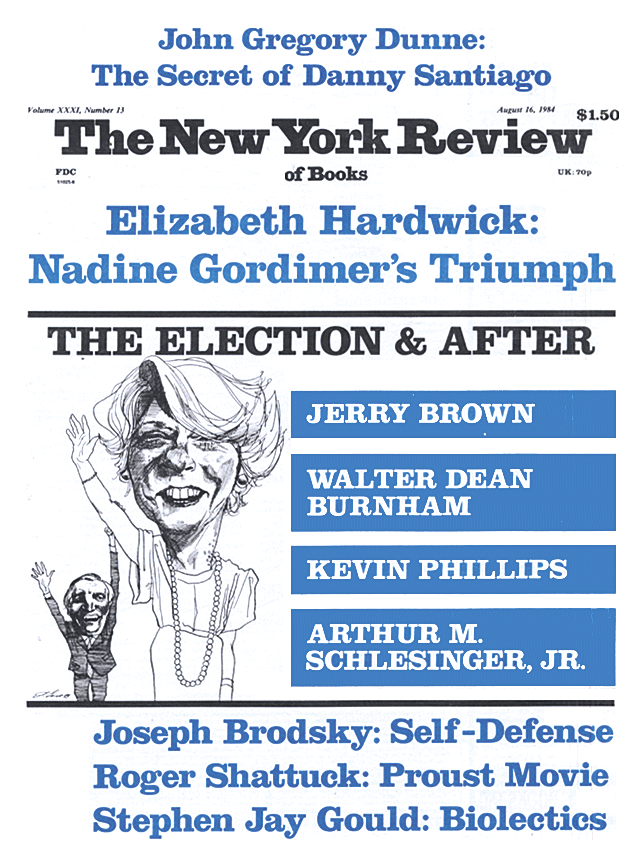

Advertisement

In a family of people basking in higher Soviet education, in schools surrounded by systematic controls, and in a literary world of deliberately half-baked books and journals, how could we have received any sense of other available culture? We never even knew of any “other” existing! What a shock it was for me in my twenty-fourth year to have somehow come across works of Mandelstam, Tsvetayeva, and Pasternak. I had them in my hands only briefly but I devoured them—and they literally threw me to my knees, physically shaking with delirium and fever. An abyss opened up before me and, unlike the normal nightmare where you can see yourself as an observer at the edge, I was thrown deep within, completely severed from whatever safe place I’d come from. All my senses of history and literature were cracked and shaken. All the pent-up possibilities of the person I might have been were stirred into motion. Was this some Polish spirit making itself felt? I couldn’t say. All I knew was that as long as I had been unable to take the Soviet civil religion seriously, there had never been any sense of anything to take its place. Clearly, I had not been looking for what now seemed to have found me. “It” had found me, as if a long-forgotten God had all along been buoying me up and guarding my soul when no one had been allowed to do this in all my years of childhood and youth.

I covet the ten years I lost to my Soviet pseudoeducation. Yet it was at twenty-four, not fourteen, that I got a glimpse of our genuine culture and actual history. It was at twenty-five, not fifteen, that I began to write. The attempts I made before were the scribblings of a child who through no fault of her own knew only half an alphabet. What I have now, in my twenty-seventh year, is an appetite and a sense of how much there is to be gathered in. Time lies before me in which to seek some truths and pull together lost pieces. I will make up those years. I won’t lose the thread, so long as I live—so long as I’m not thrown into prison or some psychiatric ward. Do I have a chance? Don’t ask rhetorical questions. There is no answer.

—Translated from the Russian by Philip Balla

This Issue

August 16, 1984