When James Boswell was twenty, he ran away from the University of Glasgow and went to London. There he meant to become a Roman Catholic, perhaps a monk. But an attentive friend of a friend diverted him with the pleasures of the town; and instead of entering a monastery, Boswell caught his first case of gonorrhea. Seldom has a career of sexual misconduct been more scrupulously documented than the thirty-five years of Boswellian excess which followed. Frank Brady, in his accurate biography, continues Frederick Pottle’s James Boswell: The Earlier Years, 1740–1769 (1966); and in his compact closing sentences finds that the illness which at last killed his protagonist was uremia, brought on by chronic postgonorrheal infection.

Boswell was perfectly willing to approach ladies of good family. Complaining about his wife Margaret, he once wrote, “Some of my qualifications are not valued by her as they have been by other women—ay, and well-educated women too.” However, he hugged his opportunities where he met them. He could indeed be faithful to Margaret (who was “moderate and averse to much dalliance”) for years at a time. He could also stop off on the way to a court of law where he was observing a trial—the law was his profession—and pick up a momentary partner. “Complete” (i.e., achieving climax), Boswell recorded on this occasion, and then added, with ill-founded confidence, “for the first and I fancy last time” (i.e., since his marriage, three years earlier). Reaching Boswell’s strenuous mid-thirties, the conscientious biographer despairs of close tracking, and says,

It seems pointless to give an extended recital of Boswell’s routine sexual wanderings during the next year. Descriptions and names slide by: “a young slender slut with a red cloak,” Peggy Grant, Peggy Dundas, “a big fat whore,” “an old dallying companion now married,” “Rubra” [i.e., redhead], Dolly.

Anyone informed of the painful effects of gonorrhea, especially under the so-called treatments of Boswell’s day, must wonder how an anxious, intelligent lawyer could take such chances. It is true that Margaret’s disposition was cooler than his own, and he felt driven to try other resources. Yet he ran unnecessary risks with miscellaneous streetwalkers; and haste or alcohol generally kept him from wearing the prophylactic sheathes that were available.

The disease mortified him. The third time he was infected, he wrote to a friend, “I am determined to be entirely rid of it, and to take still more care than ever against it.” Nevertheless, it became, along with inflamed toenails, a recurrent misery.

I suspect that Boswell got pleasure as well as pain from disgrace. He once compared himself to “a child that lets itself fall purposely, to have the pleasure of being tenderly raised up again by those who are fond of it.” His father, a judge in the highest courts of Scotland, was sarcastic and imperious. Although a good Latin scholar (like his heir), he disliked modern literature. Boswell’s mother was described by her son as “pious, visionary, and scrupulous.” She infused hellfire religion into the boy while overprotecting and overindulging him. Dependent on her as a child, Boswell was timorous, given to fantasies, but quick at his studies.

By notoriously misbehaving, Boswell might unconsciously defy the father whom he could not oppose directly. Although proud of his ancestry and of the splendid estate he was heir to, Boswell felt constitutionally unsure of his ability to maintain the great tradition. His two younger brothers were no challenges to him. John, three years his junior, was radically unstable and finally mad. I don’t think it lightened Boswell’s guiltridden sense of unworthiness to see a rival fade so dramatically. Unlike the rest of the family, he behaved kindly to John. Here is his versified sketch of the lunatic:

…sometimes on the ground

His eyes are fixed; sometimes they stare around;

Sometimes with childish laughter he seems pleased,

As if his mind were for a moment eased;

Then on a sudden shakes his hands and head….

To lighten his own frequent depressions, Boswell drank, a habit which in turn overpowered his chronic uneasiness about sexual promiscuity. Margaret, an impecunious cousin who knew his character well before she married him, had a motherly relation to Boswell. He often confessed his delinquencies to her; and although she at last lost patience, she remained, Brady observes, the steadying, wise companion—sensible, cheerful, unselfish. Instead of talking like an adult to her, he liked to prattle playfully.

Part of the trouble was Boswell’s custom of testing devotion. As a self-doubter, he had to keep proving that people really liked him. With Margaret, I suspect that the repeated revelation of selected betrayals was a way of seeing how far her love would go, and also a way of demeaning her for loving a man so undeserving as himself. When he tormented Margaret, he was perhaps evening scores with the mother who had in effect seduced him without finally preferring the son to the father.

Advertisement

Although Brady declares that he never became an alcoholic, Boswell’s friends certainly worried about the social embarrassment his drinking could produce. Public scenes, total incompetence, and blackouts occurred as he grew older. To his hosts he was often an extended vexation, although people enjoyed his high spirits, his anecdotes, and his talent for mimicry.

In his mid-thirties, Boswell said of himself, “I am sensible that I am deficient in judgement, in good common sense. I ought therefore to be diffident and cautious. For some time past I have indulged coarse raillery and abuse by far too much.” Lady Lucan, a friend of Horace Walpole’s, complained that Bosell never left her house until he was completely drunk. Lord Fife, a powerful Scottish MP, went to see Boswell in his last days, having admired the Tour to the Hebrides. But the distinguished author was not at his best. According to Fife, “The voice was so loud and he drank so much and talked so much that I decided it was more comfortable to me to read him than to hear him.”

Boswell certainly knew how to make himself agreeable. Great men and ambitious hostesses would never have put up with his foolishness if they had not valued his conversation. Yet a friend who knew him intimately from boyhood described Boswell at forty-two as “irregular in his conduct and manners, selfish, indelicate, thoughtless, no sensibility or feeling for others who have not his coarse and rustic strength and spirits…. [He] came to us in the evening in his usual ranting way and stayed till 12, drinking wine and water, glass after glass.”

Staggering drunk through the streets, he would have dangerous falls; he would be robbed; strangers would have to take him home. Fits of gambling (and losing) sometimes went with the drinking. Once his clerk found him, after playing through the night, still keeping on till nine in the morning, when he had to appear in court for a client. In a drunken rage he might break furniture and throw pieces at his wife. When he was a widower, nearly fifty, he went out to meet a whore, but was so unsteady, Brady tells us, that his eleven-year-old son followed and brought him back.

For all his carryings-on, Boswell took Christianity seriously. He condemned those who mocked religion, and searched the conduct of nonbelievers for evidence of their wretchedness or their secret faith. One acquaintance, the Reverend Norton Nicholls, infuriated Boswell by giving a ridiculous account of his own ordination. According to Boswell, Nicholls cheerfully said that when he was told to write on the necessity of a mediator between God and man, he produced “some strange stuff as fast as he would a card to a lady”; and he declared that he had never read the New Testament in Greek. Nicholls made “a very profane farce” of the whole process of ordination, said Boswell: “I shall never receive him again into my house.”

But it seems that Boswell clung to his faith with the strength of others. Had he been secure, Nicholls would not have provoked such righteousness in a man who could force kisses on a girl during a funeral service. Boswell sought out believers like Samuel Johnson and questioned them about their principles. He pursued a doubter like David Hume to his last hours in the hope of hearing Hume recant his disbelief. He followed condemned men to the scaffold, studying them, watching for some heartening disclosure of the effect of dying upon the soul. He went to Roman Catholic services and felt stirred by the rich ceremony.

Death fascinated and terrified Boswell. He missed few deathbeds that he could attend, apart from his wife’s; and he could not stay away from public executions. Once he went to the hanging of six felons, sat on a hearse to get the best view possible, and then published verses ridiculing himself for doing so. Not only did he accept ill-paying criminal cases, but he habitually defended men who were almost surely guilty. One can hardly doubt that he identified himself with such defendants and imagined unconsciously that if he could save them, he would be saved himself. In the case of John Reid, a recidivist sheep-stealer condemned to be hanged, Boswell saw the prisoner often. Two weeks before the execution, he visited Reid and urged him in a melodramatic scene to confess that he had given false evidence. As the clock struck, Boswell solemnly told Reid to consider it as his “last bell,” to look on himself as a dead man, and to admit he was guilty if he was so. Boswell wrote later,

Advertisement

The circumstance of the clock striking and the two o’clock bell ringing were finely adapted to touch the imagination. But John seemed to be very unfeeling today. He persisted in his tale.

Finally, Boswell alarmed himself:

I said, “With what face can you go to the other world?” And, “If your ghost should come and tell me this, I would not believe it.” This last sentence made me frightened, as I have faith in apparitions, and had a kind of idea that perhaps his ghost might come and tell me I had been unjust to him.

When an appeal for mercy failed, Boswell played with the scheme of cutting the body down and reviving Reid. But he finally gave it up, witnessed the execution, and then sat in terror by his own fireside. “I was so affrighted,” he wrote in his journal, “that I started every now and then and durst hardly rise from my chair.”

The obsession with death fed into an obsession with freedom of the will. In both problems the main question is whether or not a man might save himself. Boswell could not bear to think he was “a mere machine, or a reprobate from all eternity.” Yet neither could he logically refute the determinists. Raised in the odor of predestination, he felt gloomy when he faced the crux.

Moral and theological confusion did not prevent Boswell from being an accomplished gentleman. He enjoyed a splendid humanistic education and learned to write cogent, idiomatic English prose. As an adult, he never had any trouble with Latin composition or in supplying quotations from the classic authors. Although he did not acquire much Greek, his legal education was based on the study of Roman law, which he undertook at Utrecht. During his travels, he mastered French and Italian. He visited many courts of Germany and Italy. He was an avid sightseer and a connoisseur of works of art. From the age of seventeen he produced verse and prose for publication, and became a wellknown author when he was twenty-eight. He had important conversations with Rousseau and Voltaire, and unimportant conversations with the king of England. Among his intimate friends he could rank Samuel Johnson and Sir Joshua Reynolds, but he knew as well most of the literati and the leading politicians of Britain. He was on familiar terms with Goldsmith and Garrick, David Hume and Adam Smith. He also had an exceptional memory; and if he scribbled down a few hints, he could reconstruct dialogues he had heard among the great and the near-great.

To such advantages, and an ambition to distinguish himself as a writer (a career his father frowned upon), Boswell could add a hunger for attention. He wished to be noticed by celebrities, and strove not merely to meet them but also to interest them in the personality of James Boswell. One surrogate parent emerged after another as he pursued embodied fame in Edinburgh and London.

Boswell’s changeable nature frustrated his father, who even thought of disinheriting him. Instead of sympathy, the old man offered him dry advice, threats, unremitting irony. From the surrogates, Boswell asked for reassurance. When they did offer counsel, Boswell was delighted not to follow it but to record it and thereby to prove that, say, Jean-Jacques Rousseau or Samuel Johnson considered him a proper object for philosophical guidance.

London was a heavenly kingdom for a man with these instincts. Once Boswell got to know the city, it became the nursery of his imagination. The rhythm of his life was an alternation of cheerful descents upon the glittering metropolis and gloomy exile in workaday Scotland. London meant play, irresponsibility, the acting out of daydreams. There he could meet actors and playwrights, whores and countesses, sages and courtiers. Dinner parties, visits to playhouses, and the royal court varieties of religious experience offered themselves to him. Johnson told Boswell, “I never knew anyone who had such a gust for London as you have.” When he finally chose to move to the capital and make it the real scene of his private and professional life, the decision left him in an acute depression.

Apart from the tour of the islands off the western coast of Scotland, Boswell found most of the best material for his journals in London. These journals—at least, in their many vivid and dramatic episodes—have established Boswell’s high place in literary history. When one adds to them the two masterpieces that largely derive from them, i.e., the Tour to the Hebrides and the life of Johnson, one realizes that Boswell’s genius is not independent of his personality.

Readers of the life of Johnson must notice how deeply the character of the biographer animates the book. Boswell does not merely give us the annals, anecdotes, letters, and conversations of Johnson. He allows us immediate access to his own highly original self-consciousness, bathes Johnson in this light, and thereby brings us close to him.

In a brilliant insight, Brady shows how Boswell’s representation of himself as frank and artless seduces the reader. We watch Boswell respond to Johnson, and through his appreciative eyes we recognize the talents and fascination of the hero. By putting himself in a central position, Boswell provides us with the yardstick to measure his friend’s greatness. We reverse the logic of Boswell’s selfadvertising and come to feel that if a man so wordly, analytical, imaginative, and egotistic could be dazzled, Johnson must be dazzling.

Johnson would never have tolerated Boswell’s inquisitorial companionship if he had not thoroughly liked him. “My regard for you is greater almost than I have words to express,” he told Boswell. A generation younger than the childless widower, and born of a rich, well-connected family, Boswell was like an affectionate son with a successful career. His confessions allowed the ugly but passionate old man to share in the sexual escapades that had been denied him at first hand. Boswell’s boyish impulsiveness pleased the spirit of play in a scholar who wished to exhibit a taste for adventure. He willingly supplied Boswell with matter for the journal and gladly read it. “It might be printed,” he said, “were the subject fit for printing.” Boswell’s lack of discretion did not trouble a moralist who had little to hide and who delighted in truthtelling.

Boswell was aware of his own gift, and analyzed it in a memorable example of his prose style. Here he refers to the practice of working from brief notes and catch phrases:

It is a work of very great labour and difficulty to keep a journal of life, occupied in various pursuits, mingled with concomitant speculations and reflections, insomuch that I do not think it possible to do it unless one has a peculiar talent for abridging. I have tried it in that way, when it has been my good fortune to live in multiplicity of instructive and entertaining scenes, and I have thought my notes like portable [i.e., dried or jellied] soup, of which a little bit by being dissolved in water will make a good large dish; for their substance by being expanded in words would fill a volume. Sometimes it has occurred to me that a man should not live more than he can record, as a farmer should not have a larger crop than he can gather in.

For a personality sickeningly unsure of its own shape, a journal provided a therapeutic instrument of self-definition, especially when it set Boswell beside Voltaire, Johnson, and the king of England. And as Brady says, Boswell “made acute observations about others because he relentlessly observed himself.”

Boswell’s rival for Johnson’s attention was Hester Thrale, wife of the rich brewer and MP, Henry Thrale. She was under five feet tall, long-nosed, largemouthed, and well educated. She read a great deal and could write and speak with vivacity. As a hostess, she enjoyed listening and talking, performing both well. Her good humor and intelligence delighted Fanny Burney. The generous scale of her entertaining pleased less discriminating guests. While Mrs. Thrale was a talented writer, anyone who reads her Anecdotes of Johnson will see at once how pale her genius is compared to Boswell’s.

Although the friendship between Boswell and Mrs. Thrale turned into enmity, it is hard for me to agree with those who think the only connection between the two rivals was by way of Johnson. The Thrales met Johnson through a common friend, and got on so well with him that they entertained him regularly one winter. The following year, when they began to see him again, he succumbed to a depression so acute that they made him stay with them for months. Over the years thereafter, Mrs. Thrale offered him the abundant comforts of her home along with the warmth of her filial attention. Johnson experienced more happiness under the Thrales’ roof than anywhere else.

Boswell began to be invited with Johnson. Since Thrale himself had several of Boswell’s less pleasing traits and never excited his wife’s love, it is reasonable to suppose that the lady did not feel drawn to Boswell. She read his journal of the tour in manuscript but hardly commented on it. The imprudence of the writer might well have alarmed her (what would he say of the Thrales?), and she must have suspected that he would hope to see her material in return. Gabriel Piozzi, the sober, self-respecting musician whom she fell in love with, seems a very different sort. Boswell was neither considerate nor steady enough to attract her; and the clever woman’s irresponsible husband had given her ample experience of roaming passion and its consequences.

But Boswell’s appetite was less dainty. He could not have spent hours in the company of such a woman without hoping to catch her fancy. Frederick Pottle, the supreme authority, said Boswell came to feel for her “a greater degree of friendliness than he commonly granted to women.” When he turned against Mrs. Thrale, the bitterness of his anger suggests the voice of a man who has been scorned. Beneath the competition of Boswell with Mrs. Thrale for Johnson was that of the two men for the lady. When Boswell composed a burlesque ode on the imaginary nuptials of his hero with Mrs. Thrale, jealousy of Johnson was among his motives. At least, I think so.

Frank Brady’s James Boswell: The Later Years completes the biography begun by Frederick Pottle, whose The Earlier Years is reprinted simultaneously. One mark of Pottle’s stature is the number of distinguished scholars who have worked with him. (Sic itur ad astra.) For all his modesty, I cannot think of another learned professor whose integrity of character (not to mention his scholarship) is so affectionately praised by such a variety of minds and temperaments.

Like Pottle, Brady offers incomparably accurate and comprehensive information, along with penetrating insights felicitously phrased. The high point of his book is a brilliant analysis of Boswell’s moral and psychological makeup. Weighing the talents and advantages of Boswell against his humiliating defects, Brady dwells on the chronic failure of self-confidence. After linking this with Boswell’s immaturity and his lack of self-discipline, Brady wisely observes, “But he knew his weaknessess as well as he knew his strengths, and the knowledge crippled him.”

Brady’s large-scale narrative, however, is not so smoothly jointed or carefully organized as that of Pottle. Shifts of scene between Scotland and London are not always clearly marked; and Brady stays too close to the order of episodes and topics in Boswell’s journal.

At some points, Brady takes too much for granted (as in the account of the Johnson—Wilkes dinner); at others he is too expansive (as in his quoting a long verse passage merely because Johnson recited it). Brady’s focus is also unsteady: often we seem to be reading a life of Johnson. Sometimes, trying to fit everything in, Brady produces a tiresome list of disconnected events, or of themes that came up in conversation. Most unfortunately, his attitude toward Boswell veers from defensive sympathy to irritated fatigue.

The publishers have served the biographer ill. The typography is lustreless. The references at the end of the book are often keyed to the wrong pages in the text. Pottle’s book in the original printing had as its frontispiece a fine color reproduction of the portrait of Boswell by Willison. In the current edition this has been exiled to the ephemeral dust jacket, while the other illustrations (including portraits of Boswell’s parents and his wife) have vanished entirely. Brady’s book shows the portrait by Reynolds in color on the dust jacket, where few readers of library copies will see it; but the frontispiece reproduction is a fuzzy black and white; and the other illustrations also lack tone. Brady’s work is the culmination of long years of ingenious, often inspired, research. It will be the starting point for many fresh studies of a great author. It deserves better treatment.

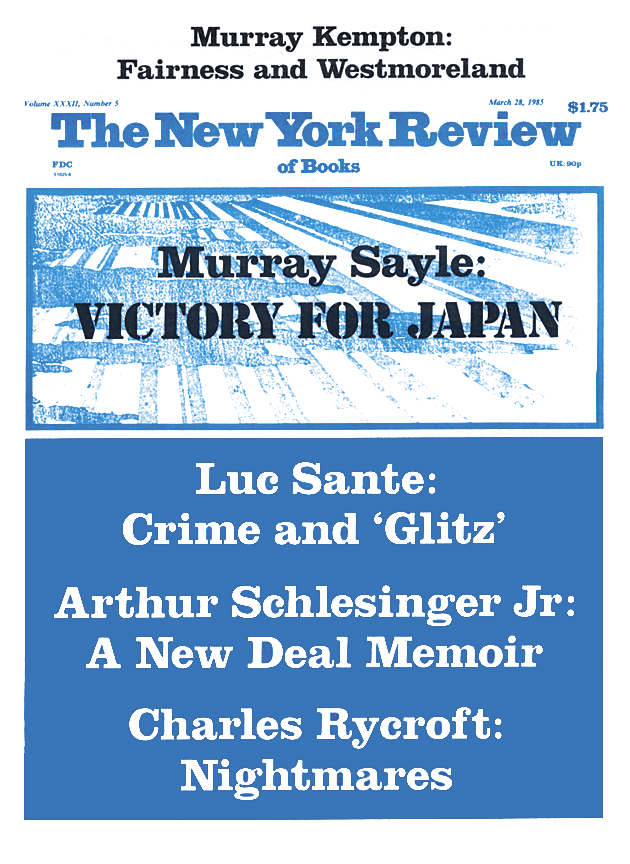

This Issue

March 28, 1985