1.

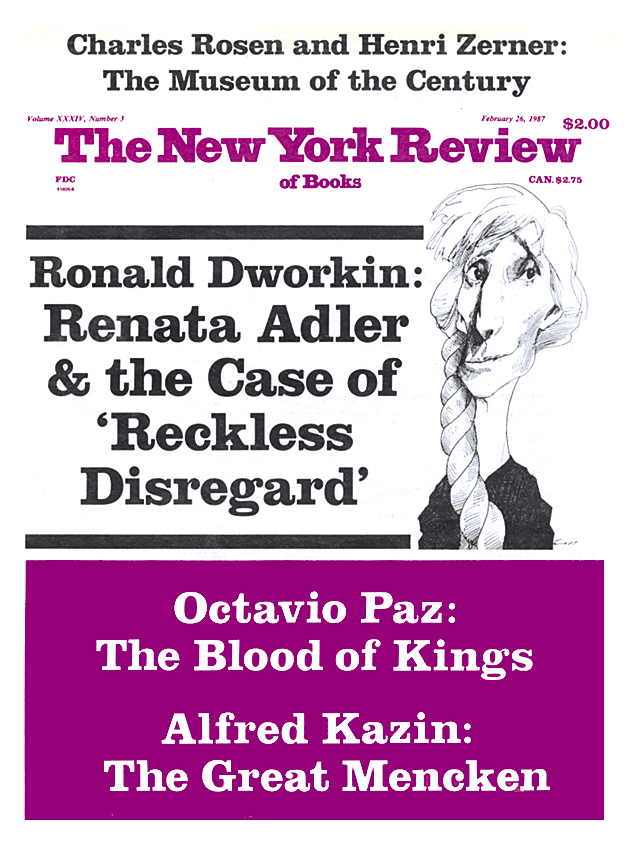

Renata Adler’s fierce book about two recent libel suits—Westmoreland v. CBS and Sharon v. Time—has revived the debates they provoked and become a cause célèbre of its own. The lawsuits themselves attracted great public attention and were widely covered in both the American and foreign press. Both cases involved commanding generals, unpopular wars, and powerful press institutions. On January 23, 1982, CBS broadcast a documentary, called “The Uncounted Enemy,” about the war in Vietnam. It claimed to report “a conscious effort—indeed a conspiracy at the highest levels of American military intelligence—to suppress and alter critical intelligence on the enemy in the year leading up to the Tet offensive,” and showed General William C. Westmoreland, who commanded American forces in Vietnam, at the center of that “conspiracy.” In February 1983, Time ran a cover story about the massacre of Palestinian refugees by Christian Phalangist troops in Sabra and Shatila in Lebanon following the assassination of the Phalangist leader Bashir Gemayel. It said that the Israeli defense minister, General Ariel Sharon, had “reportedly discussed with the Gemayels the need for the Phalangists to take revenge for the assassination of Bashir.”

Westmoreland and Sharon both sued for enormous sums. Westmoreland’s suit was financed by the conservative Capital Legal Foundation, which approached him after several firms had declined to take his case. Sharon’s principal lawyer, Milton Gould, volunteered his firm’s services. (Westmoreland said he would donate whatever compensation he won to charity.) CBS and Time were both represented by Cravath, Swaine and Moore, one of New York’s most prestigious law firms. David Boies of that firm headed the CBS team, and Thomas Barr the Time team. The trials were held at the same time (Sharon’s began later and finished earlier) on different floors of the United States Courthouse in Foley Square in Manhattan before two exceptionally able judges—Pierre Leval for Westmoreland’s trial, and Abraham Sofaer, who is now legal adviser to the State Department, for Sharon’s. These judges earned the virtually unqualified admiration of both sides and of all commentators on the cases I have read.

The plaintiffs were under a severe legal burden. The Supreme Court had held, in the famous 1964 case of New York Times v. Sullivan, that a public official cannot win compensation for libel unless he proves not only that the charge published against him was false but also that it was published with “actual malice,” by which the Court meant that the publisher knew it to be false, or published it with “reckless disregard” for its truth. Sharon’s jury decided, at the end of his trial, that Time’s statement about him was false, but that since Time had not known it to be false, he was not entitled to compensation. Westmoreland settled his suit just before his trial was to end, in exchange for no compensation—not even a contribution toward his expenses—and for a CBS statement that said only that it had not meant to call him unpatriotic or disloyal.

Renata Adler is a well-known journalist, essayist, and novelist. She is also a graduate of the Yale Law School, and therefore has formidable credentials to examine these lawsuits and their implications. She first published most of her book, Reckless Disregard, last summer, in two long New Yorker articles that were very critical of CBS, Time, and Cravath. She said that they should not have defended the lawsuits so “aggressively,” and that they cared too much about protecting themselves and too little about the truth or falsity of what they had said. And she seemed to suggest, though never quite explicitly, that the cases therefore call into question the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the First Amendment guarantee of freedom of the press, including the rule in New York Times v. Sullivan about “actual malice,” which she believes grants the press almost a sovereign immunity from the consequences of its mistakes.

CBS and Time each prepared rebuttals (CBS’s, which Cravath helped prepare, ran to fifty pages) and sent these to William Shawn, the editor of The New Yorker, asking for corrections or an opportunity to reply. (Shawn rejected the rebuttals, refused to print any reply, and pronounced his magazine content with the articles as published.) CBS also sent its rebuttal to Knopf, which was to publish the book version, and Adler charges, in the coda she added to the book as finally published, that it did so to intimidate her and Knopf by covertly threatening them with a libel suit. The Time and CBS replies delayed the publication of Reckless Disregard, while Adler checked each of the charges they made.

There is indeed much to admire in Reckless Disregard. It provides fascinating sketches of the familiar courtroom theater of testimony and cross-examination, and of the less familiar offstage depositions and “side-bar” conferences, which took place out of the jury’s hearing, between judge and counsel. (Adler attended, I believe, only some sessions of the actual trials, and her report is gathered from the considerable labor, for which she deserves much credit, of studying trial and other transcripts that, together with documents some of which she must also have studied, ran to a fear-some length of hundreds of thousands of pages.) She sets out testimony that should destroy any faith her more credulous readers might have had in the shrewdness of military intelligence or the infallibility of major news organizations, and some of her observations about the contemporary American press are refreshing and valuable. Adler’s nonlegal readers will learn a good deal about libel law and, through the lines, even more about the law governing what evidence is admissible in court and how it must be presented. Her images are often arresting: she describes the giant Time organization, for example, which relied on one journalist’s report of “confidential sources,” as “perched, like an improbable ballerina, on a single toe.”

Advertisement

But Adler often writes in dense and clotted prose, in sentences of amazing length and bewildering syntax. She writes about both trials together, moreover, jumping back and forth between the two in modern cinematographic style, letting light dawn only gradually over both lawsuits together. Though this device is presumably meant to suggest that her target is larger than the two cases, and is nothing less than the state of journalism and press law as a whole, its main effect is to obscure crucial differences between the two cases, and between the position, performance, and achievements of the two news organizations. And she too often surrenders to the very journalistic vices she excoriates. Reckless Disregard is marred by the same one-sided reporting, particularly in its account of Westmoreland, and its coda displays the same intransigence in the face of contrary evidence, that we would rightly condemn in the institutional press.

2.

Adler’s main charge is summarized in this passage:

Neither suit should ever have been brought. Once brought, neither suit should have been so aggressively defended. Because neither the ninety minutes nor the paragraph should have been broadcast or published, either. Whether it was Cravath, or the press defendants, or some unexamined, combative folly the clients and their law firm embarked upon together, the refusal to acknowledge, or even to consider, the possibility of human error caused both CBS and Time and their attorneys to spare no expense, and experience, apparently, no doubt or scruple, in transforming both suits into a contest not of mistakes but of legal and journalistic shams.

It is not clear what Adler means by the key word “aggressively.” Sometimes she seems to be objecting mainly to the manner in which the suits were defended, that is, to the demeanor and evasiveness of the press’s witnesses, and to what she considers the boorishness or craftiness of its lawyers. But sometimes she argues a graver and more important objection, more relevant to her later serious charge that the defense “trivialized” the First Amendment: that the defendants should not have tried to defend the truth of what they had broadcast or published but only their lack of “reckless disregard” in broadcasting or publishing it.

The first of these objections—about the press’s demeanor—in turn harbors two rather different accusations that should be distinguished. The more serious is that the journalists who became witnesses for the defense actually obstructed the search for truth by evasions and devious if not downright false testimony, as if all that mattered, once the lawsuits had begun, was winning them at any cost. (Though she several times implies that the witnesses for both Time and CBS were guilty of this impropriety, her more plausible examples are all drawn from the Time case.) She analyzes, in much detail, the testimony of David Halevy, the “single toe” Israeli reporter in Time’s Jerusalem office, who kept changing his story about his sources. She spends several pages on the testimony of Richard Duncan, Time’s chief of correspondents, who said he could not recall what was in Halevy’s personnel file (which in fact contained the record of a past inaccurate story by Halevy for which he had been put on probation), a failure of memory Adler, with justice, finds implausible. Duncan also said that he had stopped making inquiries about Halevy’s sources when the litigation began because “at that point the role to make that kind of investigation had passed from me to the lawyers.”

Adler makes much of these evasions, and of this apparent abdication of responsibility, and she is right to find them lamentable. But they are also, I fear, perfectly understandable. Time’s executives and reporters did not become tricky or guarded or cautious or unenterprising because its story had been challenged—the magazine had conducted a thorough and successful investigation of Halevy’s previous mistake, and published a retraction—but because Time had been sued for $50 million by a powerful man with considerable financial resources at his disposal and powerful emotional support at his back.

Advertisement

Lawsuits are frightening: they can be lost even with a sound case, and they are, in folklore and in fact, dangerous places where one incautious word or ventured fact will be seized upon by relentless lawyers on the other side and made to seem much more damaging or incriminating than it really is. Lawsuits are also, at an even cruder and more dramatic level, inescapably and deeply adversarial: the defendant finds himself confronted not by a partner in the search for truth but by an announced enemy bent on crushing him. Plaintiff and defendant are both, from the moment a complaint is filed, symbolically and actually locked into a process in which any end, even settlement, will be assessed as vindication for one and humiliation for the other. It is hardly surprising that almost everyone turns defensive (or, what is much the same thing, mock-arrogant) when he or his team is sued, and docile in the hands of his lawyers, who, in turn, are expected by client and colleague to play their own scripted role, fighting fire with fire, in the sad drama.

Litigation, in short, is a culture of its own, and the behavior of Time’s officers and witnesses must be judged, in all fairness, against the standards of that culture rather than the higher and more attractive standards of their normal profession. I do not mean, of course, to condone the evasiveness and lack of candor Adler reports; nor do I disagree with her that it would have been admirable had all Time’s employees carried journalistic integrity across the litigation barrier. The more important point, however, is that the plaintiffs have their own kind of responsibility for turning reporting into caginess; both generals had other opportunities for redress, as we shall see, and their decision for litigation itself risked sacrificing accuracy in the public record for a chance at vengeance in court. The Westmoreland and Sharon cases did show a defect in the jurisprudence of libel; this was not, however, that libel law is too favorable to journalists, but that a trial’s publicity and prospect of enormous damages make it too tempting for plaintiffs to try to take history to court.

I said that Adler’s complaints about the demeanor of the defendants contained two accusations: the second is a much more diffuse and heated complaint not just about how journalists behave in court, but about what their courtroom behavior reveals about them as people:

As early as the first depositions in Sharon, it was evident that witnesses with a claim to any sort of journalistic affiliation considered themselves a class apart, by turns lofty, combative, sullen, lame, condescending, speciously pedantic, but, above all, socially and, as it were, Constitutionally arrogant, in a surprisingly unintelligent and uneducated way. Who are these people? …Above all, the journalists, as witnesses, looked like people whose minds it had never crossed to be ashamed.

I do not know how much of this savage opinion Adler formed in her, I believe, selective visits to the trials, how much she constructed from reading transcripts (which are a notoriously unreliable guide to the figures witnesses actually cut), and how much it reflects the general impressions she has formed of her colleagues in her own career as a journalist. But it goes far beyond any evidence she supplies. She supports it mainly by quoting from the testimony of two witnesses: Halevy and George Crile, the producer of CBS’s documentary.

Halevy is (to use one of her favorite expressions) what he is: a buccaneer foreign reporter who no doubt felt himself to be (as Judge Sofaer said he was) himself at risk in the trial, and who was indeed evasive and misleading. But I found nothing socially arrogant in his testimony Adler quotes, or anything that justifies calling him unintelligent or uneducated or condescending, or supposing that he considered himself a member of a class apart. His “Constitutional arrogance” consisted only in his sometimes inapposite appeals to a New York State statute (not a constitutional provision) designed to protect reporters unwilling to reveal sources. And though Adler does find passages in Crile’s long testimony that make him seem arrogant or evasive, and others in which he went far beyond questions put to him, nothing she cites demonstrates he is unintelligent or uneducated. It is worth noting that her picture of Crile is contradicted by one of the jurors in Westmoreland, Patricia Roth, a schoolteacher who has written her own valuable account of the trial, 1 and who found Crile persuasive, patient, clear, and helpful.

I am more concerned in this review, however, with Adler’s more interesting claim about the scope rather than the manner of the press’s defense of the two lawsuits. Were Time and CBS wrong to try to prove, in court, that what they had published and broadcast was substantially true? Were they right to think, as they did, that this was necessary in order to protect the role of the First Amendment in American journalism? Or did their decision, as Adler claims, trivialize the First Amendment?

3.

Bashir Gemayel was assassinated on September 14, 1982. Sharon visited Gemayel’s relatives in Bikfaya the next day, to offer his and his government’s sympathy. A day later the occupying Israeli forces allowed Phalangist troops to enter two refugee camps in Lebanon, where these troops massacred hundreds of unarmed Palestinians including women and children. International opinion blamed Israel, whose government then established a commission, under an Israeli Supreme Court justice, Yitzhak Kahan, to investigate the tragedy. The Kahan Commission issued its report on February 8, 1983, with one appendix that was never made public. The published report assigned Sharon “indirect responsibility” for the massacre, and recommended that he resign his office, which he was then forced to do.

Time made the Kahan report the cover story for its next issue. It reported the commission’s finding of Sharon’s indirect responsibility, and then added these sentences:

Time has learned that [Secret Appendix B to the Report] contains further details about Sharon’s visit to the Gemayel family on the day after Bashir Gemayel’s assassination. Sharon reportedly told the Gemayels that the Israeli army would be moving into West Beirut and that he expected the Christian forces to go into the Palestinian refugee camps. Sharon also reportedly discussed with the Gemayels the need for the Phalangists to take revenge for the assassination of Bashir, but the details of the conversation are not known.

Sharon called this statement a “blood libel,” and sued Time for $50 million.

David Halevy had worked for Time in Jerusalem for many years, had excellent connections within the Israeli government and military (he had fought as an officer beside many of those he might have used as sources, and remained a lieutenant colonel in the military reserve), and had supplied reports, using these connections, for many stories published in Time, though one of his reports—a 1979 account of Prime Minister Begin’s supposed ill health—turned out to be false. Halevy had filed an internal memorandum on December 6, 1982, reporting that according to his confidential source, Sharon had “given the Gemayels the feeling,” in the condolence meeting, that he “understood” their need for revenge, and that the Israelis would not hinder them. When the February cover story was being written, Halevy was asked whether the secret Appendix B supported that claim. He telephoned his “source,” and then reported, apparently with a “thumbs-up” gesture, that it did. William Smith, a Time writer in New York, then changed Halevy’s phrase, about giving the Gemayels the feeling that Israel understood their need for revenge, to the rather different claim, which Time published, that Sharon “discussed” revenge with them.

Time defended itself against Sharon’s suit by claiming not just that it believed, in good faith, that its cover story was true when it published it, but that the story was in fact true. Halevy was the key witness, and he was unconvincing, constantly changing his claims about the number and character of the sources on whom he had relied in his initial memorandum. And under skillful questioning—partly conducted by Judge Sofaer—he admitted that he had never actually asked the “source” he called to confirm the contents of Appendix B whether that document in fact reported what Time said it did. He had only, he conceded, “inferred” that Appendix B confirmed his earlier memorandum by “reading between the lines” of what his source suggested it contained. Just before the trial’s end, and after patient negotiation by Judge Sofaer and direct appeals by Sharon, the Israeli government allowed Israeli lawyers for both sides to read, in the presence of Justice Kahan, not only Appendix B but also the notes and minutes about the Bikfaya meeting that had been submitted to the Kahan Commission. The appendix did not contain what Time said it had “learned” was there, and the notes and minutes did not mention any discussion of revenge.

Judge Sofaer gave the jury a highly specific set of instructions: he asked them to decide and report separately on each of the issues in the case. Did Time’s statement defame Sharon? If so, had Sharon’s lawyers demonstrated by clear and convincing evidence that Time’s statement that he had “discussed” revenge with the Gemayels was false? If so, did Time publish that false statement with actual malice, that is, knowing it to be false or in reckless disregard of its truth? The jury answered the first question “yes.” (Time had maintained that its statement was not defamatory because, it said, the most natural reading of the statement did not imply that Sharon had encouraged, instigated, or condoned the massacres, or was aware that they would take place. The jury disagreed.) Two days later the jury answered the second question “yes” as well: the jury thought that Time was wrong, not only about Appendix B, which it conceded it was, but about the Bikfaya meeting. After several days of further suspense, the jury answered the third question “no,” but it added (though this was not part of what it had been asked to decide) that it thought that “certain Time employees, particularly correspondent David Halevy, acted negligently and carelessly in reporting and verifying the information which ultimately found its way into the published paragraph.”

So though Time lost the first two battles and was wounded in the third, it won the legal war. Adler declares that Time was not guilty of serious irresponsibility in preparing and publishing its story:

With the arguably minor exception of Halevy (in misrepresenting the number, the reliability and the nature of his “sources”), all Time personnel conducted themselves professionally, and even honorably, up to and including the moment when the cover story reached the stands…. Up to and through the moment of publication, in other words, Time’s position and its paragraph were well within the rules.

That seems to me a somewhat generous assessment: Halevy’s “misrepresentations” were not, even arguably, “minor.” And surely Harry Kelly, Time’s bureau chief in Jerusalem, should have pressed Halevy about what Halevy’s various sources had actually said.

Adler absolves Time of any serious fault before publication to emphasize that her complaint is with its conduct after publication, that is, after Sharon had condemned the story and launched his suit. She thinks it was wrong of Time to defend the truth of its story, which she calls trying to “enforce” a scoop. But Time was apparently ready to accept a compromise before the start of the trial that would have qualified its story in an important way. Since Time insisted that it had not meant to suggest that Sharon had encouraged, instigated, condoned, or anticipated the massacres, Judge Sofaer proposed that Time sign a statement to that effect as part of a settlement. According to Sharon’s press adviser, who was with him during the trial and has now written his own book,2 Sharon’s lawyers had great difficulty persuading the general to accept their amended draft of that statement. Sharon said that he wanted not a settlement, but to punish Time: “Time published a blood libel about me. How the hell do you settle a matter like this? A blood libel. A blood libel you fight!” And when Time’s lawyers drafted a different version, Sharon, according to his press adviser, declined further negotiations.3 He gave the Time version only a brief glance and told his lawyers to say that they had not even shown it to him. “Time wants war,” he declared, “and that’s what they’ll get—as of tomorrow morning, in court.”4

Though Time’s story did seem to make the damaging charges Time denied it meant, its proposed settlement would in effect have retracted those charges; in any case Time continued to retract them, by denying it intended that meaning, throughout the trial. Why was it arrogant for Time, in those circumstances, to defend what it still believed to be true in substance: that the question of revenge had arisen at the meeting in Bikfaya? Why should it concede to be false what it still believed to be true?

In a mysterious passage Adler says, “To the question Why publish the story? the answer was easy: Time believed it to be true. To the question Why defend it…the answer Time still believes it to be true is not sufficient.” But why is that answer not sufficient? Adler’s answer is hard to extract from the long and dense passage, about not bearing false witness, that follows. But it comes to this: Time’s belief did not justify its defense of the suit because it had made no effort, after the story had been challenged, to verify its truth.

It is not clear that Adler has a fair basis for that claim.5 Time had made itself a prisoner of the widespread practice, on which much investigative journalism is now based, of relying on confidential sources. Reporters assure sources that their names will be revealed to no one, including the reporters’ own superiors; they think this necessary, even if it means going to jail for contempt, to get information from people who have a great deal to say and a great deal to lose if it is known that they said it. Since Watergate, at least, few commentators have seriously challenged the practice. Adler does not challenge it, for all her wry remarks about Halevy; she accepts that Time acted, in publishing its story, honorably and within the rules. But just as the practice severely limits the checking a responsible publication can do before it publishes, so, just as effectively, it limits the checking it can do afterward.

If Time and its lawyers had pressed Halevy as firmly as he was pressed at trial about the basis for his Appendix B claim, they might have learned that he had only inferred, and not been told in so many words, what he said the appendix contained. If they did learn this, they should have instructed him to be candid in deposition and at trial—as, of course, he should have been anyway. But, as Time’s editor in chief Henry Grunwald pointed out in a letter he wrote to selected journalists on other papers just before the trial ended, reporting is often based on inferences from what cagey sources say (Grunwald’s letter recalled the inferential devices Woodward and Bernstein used in their Watergate reporting). It turned out, of course, that Halevy’s inference was mistaken, but Time could not have known this before its lawyer in Israel was finally permitted to read the appendix.

The important charge against Sharon, in any case, was that revenge had been “discussed” at the condolence meeting, not that Appendix B said that it had. Justice Kahan’s end-of-trial report does not absolutely dispose of that issue: some of the notes and minutes his commission’s staff consulted may not have been supplied to the commission itself, and the “discussion” Halevy reported might never have been recorded in any minutes at all. Time claimed without contradiction that his confidential sources had proved reliable throughout his previous reporting of the Lebanon campaign, and his editors might very well have trusted what he said they said about a man whose reputation is very far from impeccable, and who, after all, had been found guilty, in the public portions of the Kahan report, of very grave and tragic errors of judgment.

As late as just before the trial’s end, when the truth about Appendix B had been revealed, Time asked Halevy to consult his source about the Bikfaya meeting yet again, and he reported that the source stood by his previous report. That might seem an odd way for Time to investigate—Wittgenstein imagined a man who did not believe what he read in the paper and so bought another copy to check it—but how else could it confirm the truth of Halevy’s report while respecting the practice of protecting confidential sources, while acting, that is, within the rules Adler says it behaved honorably in observing?

It is that practice, more than any special institutional arrogance on Time’s part, that Sharon calls into question, and Adler’s analysis inverts the character and importance of Time’s mistakes before and after publication. Though the use of confidential sources has proved, in spite of its failures in this and other cases, to be a valuable, perhaps even indispensable, means of uncovering official deceit, Sharon does show that editors must be particularly vigilant in supervising it.6 So long as the practice continues to be accepted by American journalists, however, it cannot be wrong—it does not “trivialize” the First Amendment—for a journal not to retract what it still honestly believes its reporter learned from such a source, just because the story has been denied or because it has been sued.

4.

Sam Adams was a CIA intelligence analyst in Vietnam in 1966. He formed the view, based on raw intelligence data, that the official reports on enemy troop strength circulated by Westmoreland’s command seriously and deliberately underestimated that strength. He pursued that thesis vigorously within the CIA, and devoted himself, in near obsessive fashion, to proving it after he left the agency in 1973, and in 1975 he defended his views in an article in Harper’s and before Congressman Otis Pike’s House Select Committee on Intelligence, which agreed that the scope of the Tet Offensive had been unanticipated because the military had had a “degraded image of the enemy.” Adams’s editor at Harper’s was George Crile, who later became a CBS producer. Crile thought the article was a good basis for a documentary. He prepared, with Adams’s help, a “blue sheet” outline of the program he had in mind, together with an account of the witnesses and interviews that Adams believed would support him. CBS tentatively authorized Crile to begin preparing the documentary, allowing him to hire Adams as a paid consultant.

“The Uncounted Enemy,” as broadcast, made a strong case. Mike Wallace narrated the introduction, charging a “conspiracy at the highest levels of military intelligence” to deceive the American public and the President of the United States, Lyndon Johnson, about the true strength of the enemy in Vietnam. Wallace was then shown interviewing Westmoreland, who seemed shifty and made damaging admissions. Adams repeated his accusations.

General Joseph A. McChristian, who had been Westmoreland’s intelligence chief until mid-1967, supported Adams’s view. He said that he had prepared a cable reporting sharply increased enemy estimates and showed it to Westmoreland, who had just returned from a public-relations trip to America during which he had made optimistic public statements that the “cross-over” point in the Vietnam War had been reached. Westmoreland, McChristian said, did not ask him for an explanation of the increased figures and only told him that the cable would be misunderstood and cause political problems. Other, more junior, intelligence officers, including Colonel Gains Hawkins, who had direct charge of preparing the enemy “Order of Battle,” were shown saying that they had in one way or another been prevented from reporting what they considered to be an accurate estimate of the enemy’s capacity.

Three days after the broadcast, however, Westmoreland held an emotional press conference, where he was joined by Ellsworth Bunker, who had been Johnson’s ambassador in Vietnam, George Carver, the CIA’s chief official responsible for Vietnam military intelligence, General Phillip Davidson, who succeeded McChristian as Westmoreland’s intelligence chief, and Colonel Charles Morris, Davidson’s former assistant. They all denounced “The Uncounted Enemy.” A long critical article on the documentary in TV Guide revealed that Crile had used questionable production and editing techniques to obtain the hard-hitting broadcast.

Some of these techniques violated CBS’s own guidelines for fairness in broadcasting. He had rehearsed witnesses before filming, interviewed one witness twice, allowing that witness to see film of interviews with other people before his second interview. He had not given Westmoreland proper notice about the scope of the interview; and he had edited Westmoreland’s interview to cut out qualifying remarks that might have made what the general said seem less damaging, and spliced an answer a witness had given to one question to make it appear an answer to an entirely different one. He had excluded from the broadcast, moreover, several interviews he had filmed with high officials who argued against the broadcast’s claims, including Walt W. Rostow, who had been Johnson’s national security adviser.

Even the less obviously wrong of these practices raise serious and difficult questions about journalistic propriety and constitutional libel law. Is factual advocacy—in which a newspaper or network presents the case for a view of events it itself, in good faith, has come to believe, ignoring or subordinating claims or arguments of others to the contrary—an acceptable part of journalism? If not, should the “actual malice” rule of the New York Times case be revised so that the media can be held in damages for a claim presented in that one-sided way if the claim can be shown to be false? Should different standards apply to newspapers and television broadcasters? Adler has very little to say about these issues, however, because her main complaint against CBS is not that Crile tailored his program to his thesis. She says that

easy as it may be, in retrospect (and particularly with the evidence in a lawsuit of this magnitude), to find fault with a ninety-minute broadcast, these might all have been good-faith editorial decisions, based on a firm conviction of some kind.

Her main complaint, here as also against Time, is with CBS’s behavior after it was sued.

She says that CBS acted in an aggressive, intransigent way; it behaved as if it were an affront to its high social responsibility and constitutional privilege for anyone, including itself, even to imagine that it might be wrong. But in fact CBS responded to criticism of its documentary in a way that hardly fits the description of arrogance and intransigence. It offered Westmoreland, just before he actually filed his suit, what seems an appropriate opportunity to air his rebuttal: it invited him, together with senior officials who supported him, to appear on a panel broadcast discussing the fairness and accuracy of “The Uncounted Enemy,” and to begin that broadcast with a fifteen-minute uninterrupted statement of his own position. (Adler never mentions this piece of evidence against her thesis.) Westmoreland declined that invitation, preferring to sue instead (a decision she might have pondered before reporting that he had sued in the interests of historical truth).

After the TV Guide article appeared, CBS conducted its own internal investigation, on the basis of which Van Gordon Sauter, then president of CBS News, issued a public statement which conceded editorial misjudgments and admitted that the program would have been better had it not used the word “conspiracy.” After the trial had begun, CBS offered a settlement under which it would have paid Westmoreland’s legal fees and issued a partial retraction no doubt more generous than the innocuous statement for which Westmoreland ultimately settled. Westmoreland rejected the offer: at that point in the trial he wanted a full retraction, which CBS believing what it believed, could not make.

Adler clearly cannot make the charge against CBS she makes against Time, that it did nothing to investigate the truth of its charges after they were challenged. Instead she argues that it should not have continued to believe in the truth of its documentary, which had been, in her view, proved false beyond question. The documentary could be understood as making two distinct assertions: that in Vietnam Westmoreland had attempted to deceive the press and public about enemy strength; and that he attempted to deceive his own military and civilian superiors. Westmoreland seemed particularly to resent the second of these charges. His lawyers, in their original complaint, said that both accusations were untrue; but they decided, just before the trial began, to contest only the second. So Adler means that CBS could not rationally have continued to believe that Westmoreland had tried to deceive his superiors.

She makes four arguments (spread over many isolated discussions) for that proposition: that the CBS thesis was absurd on its face; that the witnesses for Westmoreland who denied the thesis were distinguished senior officers and cabinet or White House officials who were in an excellent position to judge; that the main witnesses CBS produced were destroyed by cross-examination at trial; and that one of the program’s claims was actually shown to be dishonest, because it turned out that Crile and his associates had simply invented it to make their broadcast more exciting.

She says, in support of the first of these charges, that CBS’s thesis that Westmoreland tried to deceive President Johnson was preposterous because generals always exaggerate rather than minimize enemy strength to their superiors. That argument ignores the most profound and obvious fact about America’s peculiar war in Vietnam: it was a war the American public was willing to tolerate, certainly by the months before Tet, only if it was convinced the war could be won, and won reasonably soon, with no commitment of American troops or loss of American lives much beyond present numbers. Westmoreland himself made no effort to hide his view that press reports that the Vietcong were stronger than he claimed were damaging to his campaign. It is not incredible (although it might very well be false) that he thought it in the national interest to prevent new and higher estimates of enemy strength from reaching the press and public, even if that meant keeping those estimates from his superiors as well. Adler’s first argument relies on a generalization contradicted by the particular circumstances of the Vietnam War.

Her second argument borders on the naive. Westmoreland was indeed supported by people formerly in high office who were—collectively—in a position to know the truth about most of CBS’s charges. They testified that there was never any attempt, on the part of Westmoreland or anyone else, to hide accurate estimates. There was, they said, only a legitimate disagreement within the military, and for a time between the military and the CIA, about whether certain types of enemy personnel—in particular guerrillas and undercover villagers who planted booby traps that accounted for a considerable number of American casualties—should be listed within the number of ordinary enemy forces, as they had been earlier, or in independent categories listed elsewhere. This, they argued, was a matter of relative unimportance so long as the disputed enemy personnel were listed somewhere.

But if any deceit did take place, at least several of these witnesses, including Westmoreland’s own high-ranking subordinates, had to be parties to it, and others, including administration officials, would have been irresponsible or incompetent not to have discovered it. I do not mean to suggest that any of them lied. Indeed, it may be that everything they said was true. Or perhaps (as Rodney Smolla has pointed out7 ) their positions and the distance of time have given them a different sense now of the implications of past statements and events than wholly detached observers would have had then. CBS, in any case, had collected an impressive number of other witnesses, including military witnesses of lower rank than Westmoreland’s advocates, who were directly involved in the intelligence-gathering process, and who agreed that there was a cover-up. They said that intelligence reports were falsified and two of them said that Westmoreland had resisted reporting high estimates on the sole ground that the report would be politically embarrassing.

These witnesses may, of course, be wrong; they may misremember, or they, too, may now misunderstand past ambiguous statements or actions of others. But nothing Adler cites in the testimony of the military witnesses, for example, shows them to be failed and disgruntled officers or men with personal grudges against Westmoreland or political critics of the Vietnam War or even (to use one of Adler’s terms) that they are of the “left.” They appeared to be soldiers with a sense of honor no less vivid than Westmoreland’s. Some of them were confessing to what they regarded as failures of responsibility or initiative on their own part. And they had, to put the point at its weakest, no greater or more evident reason to lie, or to misremember through bias or self-interest, than those further up the chain of military and civilian command whom they contradicted. Crile and his associates had decided, in preparing the documentary, that they believed the military officers who reported that the figures were consciously distorted rather than those who said they were not, and even Adler concedes, as I said, that that could have been a judgment made in good faith. And nothing happened at the trial to force CBS to disbelieve all its key witnesses.

Adler’s third argument disputes this last judgment: she thinks CBS’s witnesses collapsed under cross-examination. In fact they fared no worse than the military witnesses on the other side: some of the strongest testimony for CBS was extracted, by Boies’s skillful questioning, from Westmoreland and senior military witnesses favorable to him. Adler’s argument centers on the testimony of General McChristian, whose appearance was reported as particularly distressing to Westmoreland because they were both West Point graduates, and Colonel Hawkins, who apparently impressed the jury a great deal. She examines the supposedly embarrassing parts of these two witnesses’ testimony in meticulous detail, with special concern for their faults of diction.

McChristian testified that when he prepared a cable reporting much larger enemy figures than Westmoreland had announced during his American trip, Westmoreland asked for no explanations but said only that the cable would be a “political bombshell,” words that, McChristian testified, were “burned” into his memory. Adler reports that cross-examination revealed that McChristian had said, before the trial, that he could not remember the exact words Westmoreland had used when presented with the cable. Adler claims that this “effectively disposed of the matter.”

But this apparent important victory for Westmoreland turned into what some observers thought a disaster for him, and led Bob Brewin and Sydney Shaw, in their book about the trial, to call McChristian’s evidence “potentially devastating.”8 For Boies brought out on reexamination not only that McChristian had felt it a point of honor not to quote verbatim from a private conversation with his superior until he felt forced to do so at the trial itself, but the much more damaging fact that Westmoreland had telephoned McChristian, just before or just after the CBS broadcast, saying, according to McChristian’s notes, that “he thought our conversation was private and official between West Pointers” and that “he has stood up for and took the brunt of Vietnam for all of us,” which might seem to indicate that Westmoreland himself understood the incriminating character of the 1967 conversation about the cable. (McChristian had not revealed Westmoreland’s telephone call to CBS or its lawyers, feeling honor bound to keep it private as well, and it came to light only when his papers, which included a memorandum of Westmoreland’s call, were subpoenaed by Westmoreland’s lawyers.)

After the trial, Westmoreland disputed McChristian’s interpretation of his call, and Adler might herself have formed the view from her transcripts that McChristian was dissembling about his reasons for not reporting details of the “bombshell” conversation earlier. David Dorsen, a lawyer on Westmoreland’s team, did shake other aspects of McChristian’s testimony in his cross-examination. But omitting any account of McChristian’s testimony about the telephone call from Westmoreland, while making so much of McChristian’s discomfort about which words were or were not burned into his memory, demonstrates her own weakness for factual advocacy.

Adler calls Hawkins “cornball” and “boozy,” and strongly suggests that his testimony, however engaging, came to nothing. Hawkins testified that he had briefed Westmoreland twice, in May and June of 1967, and that Westmoreland had said, in response to Hawkins’s figures, “What will I tell the President? What will I tell the Congress? What will be the reaction of the press?” Hawkins said that his superior officers constantly sent his figures back for further work, and that he finally told them that they should tell him what rules to follow and that he would then come up with figures they liked. He said, with what observers felt was shame, that he thereafter began to shave figures down arbitrarily, to keep them below what he gathered was a maximum acceptable figure, and that he had ordered his own assistants to do the same thing.

Dorsen was able to show that Hawkins could remember little of his Westmoreland briefings beyond the dramatic statements he said he did remember; and Adler emphasizes that, although repeatedly pressed to do so, he never said that he was explicitly ordered to respect what he described as a “command position” setting a top limit on enemy estimates. The case was settled before Hawkins’s testimony was finished, but if he had added nothing to what he had already said, the jury would have had to decide how to interpret his own confessed tampering with the figures. It seems incredible that he would have done this on his own initiative. Was he right in thinking that his superiors, by their frequent refusal to accept higher figures, meant him to understand they wanted him to observe a top limit, even if they had never explicitly commanded him to do so? Or did he misunderstand what was only their disagreement, in good faith, with his methods of estimating? Patricia Roth, the juror who wrote a book, seemed to accept the first of these interpretations: she thought Hawkins was a particularly destructive witness. And Rodney Smolla says that “Without doubt…the witness who did the most damage to Westmoreland was Colonel Gains Hawkins.”

So Adler’s third argument, that key CBS witnesses were destroyed, is unpersuasive. Her fourth argument seems an example of something even stronger than factual advocacy. “The Uncounted Enemy” reported that Westmoreland’s command had suppressed reports of large-scale infiltration of North Vietnamese soldiers along the Ho Chi Minh Trail into South Vietnam in the months preceding the 1968 Tet Offensive. Adler says that, whatever one might think of the other claims the documentary made, this particular charge was “plain dishonest,” that the program’s producers had no evidence whatever for this claim and simply invented it to make the program more exciting. Here is Adler’s argument for this very grave charge:

In all [Sam Adams’s] “lists,” “chronologies” and other notes, until just before he began working on the broadcast, he had never once (and neither had anybody else) so much as mentioned the more than a hundred thousand North Vietnamese who, the program alleged, infiltrated South Vietnam in the five months before Tet.

In fact two intelligence officers in Vietnam—Lieutenant Bernard Gattozzi, and Colonel (then Major) Russell Cooley—had told CBS, in prebroadcast interviews, that they believed infiltration had increased to the figures it later reported. They and another intelligence officer, Lieutenant Michael Hankins, made that claim in their testimony. And even a West Point textbook, published in 1969 and in use until 1974, which was introduced into the trial record, reports infiltration figures as high or higher than CBS cited. The author, General Dave Richard Palmer, wrote, “By November [1967], the monthly infiltration figure had reached some 30,000 men.”9 Adler does not mention this book, although Crile testified that he had partly relied on it.

So whether or not its infiltration figures were accurate—and they were challenged at the trial—CBS had apparently not invented them in an act of “plain dishonesty.” It cited its evidence for the figures in the rebuttal memorandum that Adler studied before her final revision of Reckless Disregard. Her central complaint, against CBS as well as Time, is that they refused to acknowledge even proved mistakes. But she does not discuss, in her coda, several of the CBS arguments attempting to rebut her claim that it was dishonest about infiltration. She does discuss Hankins, Gattozzi, and Cooley, but her remarks, among other difficulties, are almost all irrelevant to the crucial question whether CBS acted dishonestly in relying on their statements. Gattozzi, she says, had a “total memory block” until Crile and Adams made contact with him, which might suggest that they fed him the higher infiltration figures. But Gattozzi testified that it was he who had first raised the issue of infiltration with Adams, rather than vice versa.

She says that Hankins, who she concedes was an infiltration expert, admitted that his figures were based on new techniques that he “could never fully validate.” But that, as she makes plain elsewhere in the book, is true of almost everyone’s opinion of almost everything about enemy intelligence, and hardly shows that it was dishonest of CBS to accept his opinions. Hankins testified that he “screamed bloody murder” about the constraints imposed on his reports. Cooley testified that he believed Hankins’s methods were sound and that they had never been questioned by superiors who nevertheless did not accept Hankins’s results.

She says that Cooley had never met Westmoreland, which hardly damages his testimony that he believed the infiltration figures Westmoreland was supplying were much lower than the true figures. She says that “Gattozzi, in any event, told what he thought he had overheard from Hankins to Major Russell Cooley…”—which might suggest that the high infiltration idea was somehow the product of a one-shot and perhaps garbled communication among these three witnesses.

In fact, Cooley testified that he had learned about the understated official infiltration reports directly from Hankins, the expert, and that he, Hankins, and Gattozzi went over the great disparity between these figures and what they believed to be the truth together, not once or twice but—

continually. I mean, absolutely continually. This wasn’t a matter of once a week I received a briefing from Mike Hankins. This was a daily, this was an hourly, this was a minute, this was a from midnight to noon to 3 o’clock to 8 o’clock in the morning type of thing, not only with me, but with Gattozzi.

Adler says she has prepared a document, which she does not include in her coda, that refutes the CBS rebuttal. It might contain additional evidence for her claim that CBS was dishonest; but the coda itself does not succeed in rehabilitating that serious charge.

So Adler’s four arguments why CBS must have known its documentary to be false all fail to support that thesis, and fail badly. In fact, so far from damaging CBS’s case, the trial struck some observers as greatly improving it.10 The combination of forces Adler finds unholy—the press and their lawyers joining in an intense investigation financed by a much larger budget than CBS would ever devote to a single program, and aided by the adversarial techniques of subpoena, discovery, deposition, and cross-examination—produced a much more powerful case that the military had systematically deceived the public during Vietnam than CBS had had for its original broadcast. Members of the jury were interviewed after the trial had ended in a virtual Westmoreland surrender; these interviews suggested that several members of the jury thought, on the basis of the evidence and arguments so far, that Westmoreland had not shown that the CBS charges were false. Though Patricia Roth never says how she would have voted, her diary suggests that when the trial ended she believed CBS and not the general.

I do not mean, however, that Westmoreland proved the desirability of moving history from the study to the courtroom. We do know more, as a result of Westmoreland, than we probably otherwise would ever have known about the course of military intelligence in Vietnam; it is hard to imagine a group of scholarly historians discovering all the details that Cravath’s litigation team did. But the trial’s cost was unbelievably high, and, as Judge Leval told the jurors when he dismissed them after the settlement, even a unanimous jury verdict will not put a complex historical controversy to rest.

Adler does not agree that the trial made the CBS case stronger. But she is arguing—remember—not just that Westmoreland’s side had the better of the historical argument, which she is entitled to think, but that CBS could not rationally continue to believe its side, and she is not entitled, on the basis of the arguments and material she presents in her book, to that conclusion. She therefore has no case that CBS’s decision to defend its claims trivialized the First Amendment, or illustrates a general, institutional arrogance in the American press that requires reexamining the constitutional jurisprudence of press freedom.

5.

Adler’s comments about the First Amendment, and about the New York Times v. Sullivan rule that a public official must prove “actual malice” to win a libel suit, are brief, obscure, and dangerous. She says that the press in the eighteenth century, when the First Amendment was adopted, consisted of a number of small journals representing a wide range of radically different political points of view whose audience expected biased reporting. She concludes that

the Constitution can hardly have envisioned, on the part of the press, a power, a scale and, above all, a unity, which is in part, but by no means entirely, a result of technological advance.

She plainly does not intend what might seem a natural implication of these remarks: that the First Amendment guarantee of a free press does not extend to the contemporary institutional press at all. She presumably does intend these observations to have some force and relevance to her essay, however; she apparently thinks they justify a less generous measure of First Amendment protection than the press now claims, at least in libel suits, though she does not, so far as I could discover, say even that in so many words. In any case the skepticism her remarks suggest about the importance of press freedom in contemporary American society will strike many readers, already hostile to that freedom, as the most important aspect of her book.

Why does it matter that today’s press is very different, in power and influence as well as character, from the small publications and pamphlets with which eighteenth-century statesmen were familiar? Adler might be making the fallacious argument that the fact that “the framers can never have contemplated” the modern press is decisive about how the First Amendment should be understood. That argument relies on the discredited thesis Attorney General Meese has done his best to revive: that the abstract provisions of the Constitution, like the First Amendment, should be interpreted so as to protect individuals and institutions only in the concrete circumstances the statesmen who first adopted the provisions had in mind. It relies on that discredited thesis, moreover, without supplying any evidence that the framers intended to limit freedom of speech and press to the broadsheets and pamphlets that were familiar to them.11

It is more likely that Adler means, however, not just that the framers could not have anticipated the power and role of the modern press, but that the best understanding of the point and purpose of the freedom they created does not justify extending that freedom, at least in the most generous way, to the giants of international journalism. Even if she thinks it follows only that the press deserves less protection in libel suits, her argument is unacceptable, because the wisdom of the special burden the “actual malice” rule creates for public figures depends not on the character of the press alone, but on a comparison of the press’s power with that of government and the other powerful institutions we expect the press to watch.

If the press has developed far beyond its eighteenth-century situation in power and resources and influence, government has developed much further, not only in the scope of its operations and enterprises, but also in its capacity to keep its crimes and abuses dark. Indeed, these two institutions have grown in power together, in a kind of constitutional symbiosis: the press has the influence it does in large part because much of the public believes, with good reason, that a powerful and free press is a wise constraint on official secrecy and disinformation. The most basic intention of the framers was to create a system of balanced checks on power; the political role of the press, acting under a kind of limited immunity for mistakes, now seems an essential element of that system, exactly because the press alone has the flexibility, range, and initiative to discover and report secret executive misfeasance, while allowing other institutions in the checks-and-balance system to pursue these discoveries if and as appropriate. Though the Iran–contra affair was revealed after Reckless Disregard was published, it provides an excellent example of the press’s role in the complex constitutional structure that America, distinctively, has evolved.

CBS’s documentary, though marred by culpable editorial misjudgment and one-sided presentation, was another example of that role, because it placed before an American audience serious and apparently honest military officers who reported that their superiors had deceived the people about a terrible war that cost the nation heavily. Whether or not history finally judges that report to be true, it was obviously in the public interest that these officers be heard, and it was a small triumph of journalism to persuade them to speak. It is, of course, a further question whether the press would be significantly inhibited if it were subject to the ordinary rules of libel, before New York Times v. Sullivan. But the Supreme Court’s judgment that it would be seems right: even rich papers and networks would hesitate before printing or broadcasting damaging statements they were not certain would not be thought false by a jury. Or even statements they knew were true but did not wish to defend in expensive and protracted litigation brought by public figures financed by political groups seeking political goals. That, in any case, was the Supreme Court’s rationale in New York Times, and it is in no way damaged by Adler’s claims, even if we accepted them, about the monolithic and arrogant press.

Adler says the New York Times case was “historic” and “fair” and “rightly decided”; but she also says that it was “strange,” and “not very carefully reasoned” (she never even hints what its flaws of reasoning were), and that later Supreme Court decisions refining the doctrine of the case produced such “unintelligible formulation” that “something is seriously amiss.”12 And in her coda she suggests, in a backhanded way, that the rule should be changed; she notes, as a qualification, that any change the Rehnquist court made would likely be a radical change for the worse. If Adler is a critic of the New York Times rule, she has a lot of company, and though this includes right-wing antipress fanatics, it includes some serious scholars and Supreme Court justices as well.

The facts of the New York Times case show why it appealed to the Supreme Court when the case was decided. The Times had published an advertisement placed by a civil rights organization which contained some inaccurate statements about the police of Montgomery, Alabama. A Montgomery official, who was charged with supervising the police, sued the paper in an Alabama court, alleging libel, and the local jury awarded him half a million dollars in damages. The jury had been instructed that unless the defendant in a libel suit of this kind proves his statements true in every damaging detail, the plaintiff is entitled to damages, even though the defendant published the statements in good faith, that is, even if he believed them.

In the Supreme Court, the Times argued that the Alabama libel rule, as applied against it in this case, violated the First Amendment’s guarantee against laws abridging freedom of the press.13 Some lawyers argue that the First Amendment effectively abolishes the law of libel altogether, because any law allowing damages for any publication abridges freedom of speech, and justices Hugo Black, William O. Douglas, and Arthur Goldberg voted to overturn the jury’s verdict against the Times on the straightforward ground that no state has a right, under the Constitution, to award damages in libel for any statement defaming a public official. But the majority of the Court rejected that simple rule, and instead constructed the more complex “actual malice” rule. The Court held that since the Montgomery plaintiff was a public official, and since the evidence did not show that the Times either knew that the contested statements were inaccurate or was indifferent about their truth, the decision of the Alabama jury must be overruled.

No one denies that the actual malice rule has unattractive consequences. It deprives many public figures of compensation for financial and other loss when false reports are published about them. The rule has other costs as well. In Herbert v. Lando, the Supreme Court decided, properly, that if a plaintiff cannot succeed in a libel suit unless he proves that the defendant had a certain state of mind when he published—that he believed his statements false or acted in reckless disregard of whether they were true or not—the plaintiff must be allowed to examine the defendant’s reporters, editors, and executives, in pretrial depositions as well as on the witness stand, and to see at least some parts of their notes and other preparatory material, to determine what their state of mind actually was.14 This aspect of the rule has proved disruptive to the ordinary activities of newspapers and broadcasters who defend libel suits.

But these patent disadvantages do not in themselves prove that the New York Times actual malice rule is a mistake; its opponents must show that there is a better way to reconcile an individual’s interest in his reputation with the public’s interest in open government. Adler contributes nothing of value to the debate about the actual malice rule—and wastes a valuable opportunity to do so—by seeming to trash it, at least in some of her remarks about it, without offering any alternative rule against which it might be tested. Worse, much of what she says about the rule is so misleading that it can only injure public understanding of the problem.

She wildly exaggerates the legal force of the rule, for example. She says, about Westmoreland and Sharon, that “the main legal point, however, was this: that in the unlikely event that either of them should prevail before a jury the decision would almost certainly be reversed upon appeal.” And she repeats this remarkable opinion later in the book: “Both would, as a result [of the actual malice rule], if not immediately then at some appellate level, have lost their cases.” But people held to be public figures have won libel cases: Carol Burnett’s famous victory against The National Enquirer was upheld on appeal, though her damages were reduced; and when William Tavoulareas, the president of Mobil Oil, won a suit against The Washington Post largely, it seems, because the jury misunderstood or ignored the judge’s instructions, the verdict was upheld in the D.C. Court of Appeals in a decision in which Antonin Scalia, who has since been promoted to the Supreme Court, concurred. (The case has been reheard by the entire D.C. Circuit, en banc, and the entire court’s decision, when announced, may be appealed to the Supreme Court.)

If Adler were right, in this judgment about “the main legal point,” each of the judges she praises would have made a very serious and expensive mistake of law. Both defendants, Time and CBS, moved for “summary judgment” before the trials; a summary judgment motion argues that even if every assertion of fact the plaintiff makes were accepted by a jury, the plaintiff would still not have made out a valid legal claim, and that the judge should therefore save everyone time and expense by dismissing the lawsuit at the outset. If Adler were right, these motions should have been granted, in which case the long and expensive trials would never have taken place. She makes no effort to state, let alone answer, the arguments the judges made for refusing summary judgment. Moreover, she herself believes, as I said, that CBS simply invented one of its charges to make its broadcast more interesting. If Westmoreland had supplied clear and convincing evidence supporting that charge, and if the jury had accepted it and decided for him on that ground, there is no reason to think its verdict would have been overturned on appeal.15

Though Adler makes no suggestions for ameliorating the disadvantages of the actual malice rule, or amending or replacing that rule, others have made such suggestions. Judge Leval, for example, after the CBS trial had ended, proposed that if a public figure objected to a report about him in a paper or broadcast, he and the publisher might agree to a form of arbitration in which the only issue would be the truth of the report rather than the good faith of the publisher; the agreement would provide that if the report is found to be false in the arbitration, the publisher would report that fact publicly, in a fashion the agreement would stipulate. This suggestion would prove useful in some circumstances—the arbitration would be much less expensive than a trial that probed the motives of the defendant’s various reporters and editors as well as the truth of its statements—but it would require the consent of both parties.

Justice White recently revealed that he has changed his mind about the New York Times rule he once warmly endorsed.16 He said that the rule often works against the First Amendment goal of providing a free flow of information to the public, because it prevents a public official from challenging false information, and so allows falsehood to “pollute” the record on which the public makes its decisions. White made various suggestions. One of these is available under the New York Times rule as it stands: instructing the jury to announce decisions on the issues of truth and actual malice separately, so that a public figure might at least have the satisfaction and benefit of a declaration of his innocence even if his failure to prove reckless disregard prevents him from winning financial compensation. (Judge Sofaer, as I said, used that technique in the Sharon case, and it allowed Sharon the “moral” victory of a jury finding that he had not discussed revenge with the Phalangists. Judge Leval wanted to use the same technique in Westmoreland, but—though Adler makes no mention of the fact—Westmoreland’s lawyers joined with CBS in opposing it.)

White’s other suggestions would require more doctrinal changes. He proposes, for example, that even a public official be permitted to win a libel suit without showing actual malice if he asks merely nominal damages, or compensatory damages to reimburse him for his legal costs and for any actual financial loss he proves he suffered. The New York Times decision was aimed at protecting the press from large, punitive damages, and White’s suggestion has the merit of barring extravagant financial demands while at the same time allowing a defamed public official to recover something. But the costs of defending a libel suit, even one limited to the issue of truth, are very great, as Sharon and Westmoreland demonstrated, and White’s suggestion might therefore reinstate a large part of the chilling effect prospective litigation would have on a newspaper’s decision whether to publish information the public should have.

It might be more effective to amend the New York Times doctrine in a different and more comprehensive way. Many states (including California) have statutes providing that if a newspaper is challenged as having falsely defamed someone, and prints a timely retraction as prominent as the original story, that retraction will be an adequate defense to any suit for punitive damages. This strategy might be expanded, and brought into First Amendment law, through the following set of rules. A public figure who proposes to contest a defamatory statement published or broadcast about him must first challenge the publisher either to print or broadcast a timely and prominent retraction, or to print, broadcast, or accurately report a rebuttal of reasonable length prepared by him. If the publisher refuses to do either, then the person defamed may sue and win substantial compensation if he persuades a jury that whatever evidence he cited or supplied, at the time he challenged the publisher to retract its statement or report his rebuttal, provides clear and convincing evidence that the publisher’s statement about him was false.

This set of rules has clear advantages. Suppose they were adopted. If a retraction or rebuttal were published, then White’s concern, that the public record might be forever corrupted by false information, would be met. If not, even a public figure would have an opportunity to defend himself in court, and the issue that under New York Times has proved to be both an imposing burden for plaintiffs and a source of great expense and wasted time for both parties—the issue of the defendant’s state of mind when it published—would play no role whatever in the litigation.

Instead argument would focus on the question that should, after all, be decisive: whether the statement the plaintiff challenges had been shown to be, on the state of the evidence the plaintiff was able to produce to support his challenge, a doubtful matter, in which case the plaintiff would and should lose, or plainly false, in which case he would and should win because the press should not deny its victim the opportunity to disprove what is patently not true. The press would be given somewhat less protection under these rules, at least in some respects, than it enjoys under New York Times. But it would be saved great expense and difficulty, if it is sued, by not having to defend its honesty and good faith or even the reasonableness of its judgment when it published. It would be free to provide the public with information that it believed to be true on the evidence then available, with no “chilling” fear that if better evidence later showed its report false it would be punished financially by a vengeful plaintiff.

There are, of course, objections to the suggested rules even in the rough form in which I have described them. It would be necessary to draft adequate guidelines for the adequacy of a retraction or report of a rebuttal; the experience of the states with retraction statutes suggests, however, that adequate guidelines could be constructed. The rules might encourage particularly unscrupulous papers to libel people at will, cheerfully printing retractions later. This could be avoided by further refinements, but the irritation such papers could provoke might be an acceptable price to pay for keeping libel law simpler. The suggested rules might help to make that law simpler in another way: I see no very strong reason why they should not be applied to private people as well as public officials and figures. The distinction between public and private figures, and the attempt to define a separate standard governing libel suits by the latter, have proved very difficult,17 and it would be a considerable benefit to eliminate the distinction altogether.

It might be useful, finally, to consider how the Sharon and Westmoreland stories might have been different if something like these rules had been in force. CBS’s offer of a panel broadcast, opened by an uninterrupted fifteen-minute presentation by Westmoreland, would presumably have counted as an adequate opportunity for rebuttal. So there would have been no Westmoreland case. Time might have been willing to publish the “interpretation” of its remarks it offered before and during the trial, which withdrew the most damaging implications of its report. Since Halevy insisted that his sources continued to confirm their report of the Bikfaya meeting, Time would not have conceded error in that report as reinterpreted. But it would have had strong reason to print or report Sharon’s own denial, together with those of whatever witnesses he was permitted by Israeli security law to quote, as well as to report that it had had access neither to Appendix B nor to any official reports of the Bikfaya meeting. For its lawyers would very likely have told Time that there was a good chance, if Halevy’s sources remained confidential, that a jury might decide that no reasonable person would believe their story in the face of these denials. (That is, after all, what the Sharon jury in effect decided, though, it is true, with the benefit of Justice Kahan’s report about his commission’s documents.)

So the Sharon case might never have occurred either; if so, the hypothetical rules would have spared our legal system much cost and effort. And Renata Adler’s great talents and energy, and her flair for provocation, would have been put to what I am confident would have been better use.

This Issue

February 26, 1987

-

1

The Juror and the General (Morrow, 1986). ↩

-

2

Uri Dan, Blood Libel: The Inside Story of General Ariel Sharon’s History-Making Suit Against Time Magazine (Simon and Schuster, to be published in March), pp. 105–109. Sharon claimed that Time was guilty of a “blood libel,” which suggests not only an attack on him personally but on the Jewish people as a whole. ↩

-

3

Adler reports none of the details of this settlement attempt, saying only that it was Time that “turned away” from it, which is contradicted by Dan’s account. ↩

-

4

Contrary to Uri Dan’s claim that Time‘s version “bore no resemblance to the text that Sharon had accepted so reluctantly,” it differed in substance from that text only in stating that Sharon was now satisfied, on the basis of statements Time‘s employees had made in the course of discovery, that it had not meant to suggest that he had encouraged, condoned, or anticipated the massacres. It is unclear why Time asked for that addition—its journalistic integrity did not depend on Sharon’s opinions about its motives—and it should have been ready to drop or qualify the addition in negotiation, and might have done so. In any case, if Sharon had cared only about the accuracy of Time‘s statements about him, and not about punishing Time, he would not have barred further settlement discussion in the way Dan reports. ↩

-

5

Duncan testified, at the trial, that he had made no attempt to investigate Halevy’s sources, after the lawsuit began, because “a very big investigation” had been launched by Time‘s lawyers. It hardly follows that no one at Time tried to check the story in any way before the suit began (Sharon’s first suit, in Israel, was begun less than two weeks after the magazine was published) or that Time would have defended its story in court if its lawyers’ investigation had shown that story to be false. In this letter to The New Yorker, Henry Grunwald, Time‘s editor in chief, denied that it had made no investigation, and observed that Adler made no effort to interview the magazine or its lawyers about its efforts to check the story. (In her coda, she says that her book is based on trial attendance and transcripts and “does not purport to contain interviews,” which are not part of the “genre of trial reporting.” That hardly explains why she did not try to check, in the most natural way, a serious charge on which much of her argument is based and which could not have been sustained on the trial records alone.) She should at least have said what Time or its lawyers might have done, but did not do, to satisfy themselves that the story, as they now presented it, was true. ↩

-

6

I agree with Adler that the conventions for reporting information gathered from confidential sources (e.g., “Time has learned ”) often pitch these reports at too confident a level. It would be more careful of the truth to develop different conventions: “Time has been told ” for example. ↩

-

7

Rodney Smolla, Suing the Press: Libel, The Media, and Power (Oxford University Press, 1987). ↩

-

8

Vietnam on Trial: Westmoreland vs. CBS (Atheneum, 1987). Brewin covered the trial for The Village Voice. ↩

-

9

From Readings in Current Military History (United States Military Academy, 1969), p. 102. ↩

-

10

For a fuller account of CBS’s evidence and discoveries than Adler provides, see “The Strategy of Deception in the Vietnam War,” Philadelphia Inquirer Magazine (October 27, 1985), by David Zucchino, an Inquirer reporter who covered the trial day by day, and Vietnam on Trial, the Brewin and Shaw book cited in note 8. Smolla, in the book cited in note 7, says that even after the trial reasonable people could have disagreed about whether the views of Westmoreland and his many powerful supporters or those of CBS and its mainly more junior military witnesses were closer to the truth. This moderate view hardly supports Adler’s claim that the CBS position has been proved false. ↩

-

11

For a good discussion of the complexity of any argument about what those who made the Constitution intended, see H. Jefferson Powell, “The Original Understanding of Original Intent,” Harvard Law Review, vol. 98 (1985), p. 885. ↩

-

12

She has in mind Justice Byron White’s attempt, in a case after New York Times, to describe the state of mind of “reckless disregard” in more detail. He said: “There must be sufficient evidence to permit the conclusion that the defendant in fact entertained serious doubts as to the truth of his publication.” (St. Amant v. Thompson, 390 US 727 [1967] at page 731.) Adler suggests (though she seems to retract this in the coda) that White meant, by “serious doubt,” that anyone who is aware of arguments against what he publishes, or knows that he might be wrong in what he says, is guilty of reckless disregard, and she says that it cannot have been the intention of the framers to discourage good-faith doubt of that kind and to protect only those who publish in absolute and dogmatic certainty. But of course (as White’s opinion makes plain) the serious doubt he had in mind is not the normal, commendable, scholarly sense of fallibility, but the very different attitude of someone who thinks that the evidence against what he says is about as strong as the evidence for it, but publishes anyway in disregard of the contrary evidence. ↩

-

13

The Court had earlier decided that the First Amendment is made applicable to the states as well as the federal government by the Fourteenth Amendment. ↩

-

14

441 US 153 (1979). ↩

-

15