Are biographies running away with themselves? Bernard Berenson, an art connoisseur whose writings are not much read any more, has been the subject of two biographies before this one, has been written about three times in this journal, and now appears again in the second and final volume of the authorized biography—nearly seven hundred pages long. Perhaps the answer is that biography is no longer the official tribute to rare genius but a form that examines life through the medium of one person’s story—to some extent taking over territory that used to belong to the essay. If there were documentation enough and the biographer were skillful enough, any one person’s life might serve. For those who like biography as a medium for examining feelings and actions and ideas (I do), these seven hundred pages will not be too long; for others, they well may be.

Although this second volume covers a longer span of years than the first (from the age of thirty-eight to ninety-four), those first thirty-eight years were perhaps the more attractive to read about. They covered the growth of the ten-year-old from a Lithuanian ghetto into a brilliant Harvard student and then into a man who after much delay settled to choosing a career, a wife, and a country (one single complex decision that he was to agonize over for the rest of his life). Inevitably much of this volume, especially the latter part, which deals with old age, consists of a repetitive record of the Berenson yearly round—the regular trips abroad, the regular stream of visitors to I Tatti, the regular output of letters to and from correspondents all over the world.

For the documentation is enormous. Berenson had a complex attitude to the act of writing; in his Sketch for a Self-Portrait written in 1940–1941 he said that writing—serious writing for publication—caused him agony. His “neurasthenia,” his rages, tended to be associated with times when he was trying to produce a book. He laments in the Sketch his inability to express, to find a prose style fit for what he was trying to say. Yet of free writing—letters and, in age, diaries—he was an inexhaustible producer. He compared this writing to a kind of excretion; he had regularly to spill it out. So there are innumerable letters; in addition, his wife’s frank correspondence and diaries, his second “wife’s” memoirs of him, the Sketch, the diaries of old age, and the comments of the vast number of distinguished people he entertained. Professor Samuels has threaded his way through the jungle with great success. He is lowkey, however, about psychological analysis of the characters he deals with.

When the book opens Berenson, at thirty-eight, was well settled into the role of professional connoisseur, which he so often complained had distracted him from some higher destiny. He had spent a number of years after college traveling and absorbing art, while his contemporaries settled into jobs; at a very young twenty-five he had met Mary Costelloe, who left her husband and children for him; they had become a team, traveling and cataloging pictures; he had started to write, and to act as paid adviser to collectors. Her feeling about their teamwork was that without her he would have just gone on drifting; his was that without her behind him he would never have got involved in the sordidness of the art market. They had eventually married (not without some reluctance on his part); and they had just returned from a highly successful trip to the United States, where Mary had lectured and Bernard made useful contacts from whom he could hope to make the income he needed.

In his long old age Berenson was a work of art himself (so he wrote), a legend, a curiosity. But at thirty-eight the triple knot of money, career, and marriage was tightening around him. To turn his passionate love of paintings into a life work had started as a disinterested aim. “We are the first to have no idea before us, no ambition, no expectation, no thought of reward,” he had said to a friend; they would dedicate their lives, give themselves up to learning. “No thought of reward.” But he needed money; he needed a lot. Burning with a hard gemlike flame, the Paterian ideal he never relinquished, implied some comfort and exquisiteness; and in addition he supported with great generosity his siblings and parents in Boston. In 1904, Mary was writing to him that it was essential that “the New York people will take the Greco. Otherwise, I know not what we shall do.” Avoid, at any rate, paying the dentist’s bill of £15, she advised. Mary’s openness about earning money was one of the many crudities that exasperated him.

Advertisement

Helping his patroness Mrs. Isabella Gardner build up her collection was one thing. (Though how did he feel about writing to her that she was a miracle, a goddess, “the most lovable person on earth”?) But Mrs. Gardner at this time was running out of funds, and from month to month earnings were precarious. Two things happened to tighten the knot in the years 1904–1912. Berenson first started to work for Duveen, the piratical art dealer; and he bought I Tatti, which he had been renting, and began to model it after his ideal. Every time Duveen was able to make a sale because its provenance was authenticated, books could be bought for the library, architectural additions made, and checks sent home to Boston.

The tie-up between money and the visual arts, compared to the other arts, is an extraordinary one. Scholars debate whether certain marginal plays are partly by Shakespeare or not, but it is of no great interest to the reader and the debatable plays are clearly inferior. If a composer partly draws on another’s work it is at the most a curiosity. But the paintings of the period Berenson dealt with led straight into a maze. The idea of unique authorship had once been of minor importance, and a great painter could have left a picture to be finished off by a student. Then paintings, in all honesty, were copied—there were no reproductions. The work of cleaning and restoring could produce virtually a new picture. And lastly there were deliberate fakes. Berenson loved to apply his mind and perceptions to paintings above anything else. But the strange situation would be that a picture that seemed to all beautiful would, if it were by Giorgione, be worth far more than if it were by Titian. To a great many people this mattered enormously. The picture, through it all, just remained beautiful.

During the earlier part of the period this volume covers, Berenson was often driven and desperate, though he was soon earning a great deal of money. He had breakdowns when he took to his bed with “neurasthenia.” He had appalling rages; Mary found him repeating that “there was no one he could trust to carry out his wishes, that he hated this house and all Italy, that life was hell, and he was going away never to see it or us again. Dr. Giglioli says it seems to him very serious…. And yet we are all working for him in every way.” When his sister Bessie visited she told Mary that after seeing her father’s rages and Bernhard’s she would never marry; and she did not. His other sister wrote: “What food for thought in this whole situation. Culture almost overacquired, great wealth amassed, exquisite beauty enhaloing their lives, yet the flavor of dust and ashes.” Lytton Strachey, one of the innumerable guests welcomed with generosity, wrote damningly:

B.B. is a very interesting phenomenon. The mere fact that he has accumulated his wealth from having been a New York guttersnipe is sufficiently astonishing but besides that he has a most curious complicated temperament—very sensitive, very clever—even, I believe, with a strain of niceness somewhere or other but desperately wrong—perhaps suffering from some dreadful complexes—and without a spark of naturalness or ordinary human enjoyment. And this has spread itself over the house which is remarkably depressing…. One is struck chill by the atmosphere of a crypt.

At the center of Berenson’s despair was his ambivalence about his marriage. When he very first met Mary she came to the door to meet him suckling a baby; he was shocked. Yet, as Mary wrote to him when they were aging, apparently “it was because thee found me real in a world of shadows that thee cared so much.” She had the ill luck to remain appallingly real. She had been a lively, careless girl, not pretty, and she became a lively, large lady about twice the size of the little aesthete. His many adulteries seem to have been a matter of delicate afternoons unmixed with too much reality; Mary remained conspicuously there, reminding him of flesh, reminding him that dealers were arriving and bills must be paid. His affairs she had to learn to patronize, and also subtly undermine; she told him that his lover Belle Greene was delightful but,

One thing, dear, I want to say in thy ear, Don’t boast to her, either of thy moral or intellectual qualities. She will enjoy them more finding them out…. Excuse this marital word but I want thee to appear at thy best and I know how young people laugh at our middle-aged self-complacency.

He raged, he pushed his food away, he swore for the hundredth time that she had ruined his life.

Advertisement

What he actually wanted, he said, was that she should “with spontaneity and eagerness put me first in everything”; he wanted a woman with “no other thought or interest but himself.” Mary, always fond of him, commented to his sister that after all “men are not so thrillingly absorbing as all that.” He discussed with a friend “a poetic cult of woman” without which life would not be worth living. “Yet of woman,” commented Mary, “neither of them think very highly. I cannot say I find in my heart a mystic cult of Man. I wish I had.” “Woman” meant for him

halcyon days in the cold winter of our discontent when we seem to enjoy a truce from the struggle of self-assertion to abandon oneself to the abandon of a woman who seems to live and breathe only for us…to pick out with a lobster fork all the sweetness that life has to offer in its most inaccessible tentacles.

Woman as mystic cult and lobster tidbit. Mary, of course, was not woman; she was his wife.

Yet he was immensely dependent on her; she went frequently to visit her children, and far from feeling relieved at this break from his exasperating companion, he behaved each time like a child whose mother is preoccupied by siblings. As for having children, there was no question of this being life enhancing; when Mary was pregnant he made her have an abortion. His house was hung instead with paintings of Madonna and child.

And yet—it is possible to agree with the visitor who said that Berenson was lovable but not likeable. Mary never came to hate him, even when he had installed Nicky Mariano as second “wife” and relegated Mary to an invalid’s bedroom. In her diary musings she would come back to the fact that he had not bored her, that she had had immensely interesting times with him. As he grew older and had the devoted Nicky to cosset him he did struggle toward some selfknowledge. For Mary’s fifty-second birthday he wrote:

I wish you well, dear companion of my life. I ask only that we may never be parted. With all my rages so furious and denunciations so eloquent, I love you as I love the human not-me, and my denunciations and rages are through you directed at that; but I would not and could not be without you.

She was the human not-me in a way that the crowd of friends and correspondents and temporary mistresses were not.

In 1911 Mary had reflected that it was

rather awful to think how many people live off B.B.’s interest in Italian art…. Seven servants, six contadini, two masons, one bookkeeper, one estate manager, and their wives and children and then me, with a mental trail behind me of all the things I do and the people who look to me. And then B.B.’s whole family. Really it is a lot for the shoulders of one poor delicate man.

As middle age and beyond arrived, the strangling knot loosened. Berenson still had to live the double life, closeted with dealers in the morning and aesthete/host in the afternoon (“I receive like a dentist every morning and like a femme du monde in the afternoon”). But wealth was now assured; and the great plan of his life, to leave I Tatti to Harvard as a study center, was maturing. Every year there were wonderful travels in search of new treasures; he worked continually at his documentation of Italian Renaissance pictures, and brought out books. After the First World War, which he spent at I Tatti, his life was greatly changed by the arrival of Nicky Mariano, first as librarian and then for the rest of his life as mistress, secretary, nurse, hostess. She had not Mary’s tactlessness and independence of spirit, and was the completely devoted woman Berenson had been looking for. Mary liked her and came to accept the role of resident exwife.

Among a host of other prejudices Berenson came to hate Germanic scholarly art criticism in these years, which he felt supplanted his own. He did use art-historical criteria; in assessing one painting, for instance, he cited the historical appearance of a certain kind of cross, the posture of the Virgin, the presence of the Infant John, even the folds of the Virgin’s clothes. But mostly he stressed endless looking: “the hypnotic effect of merely detailed showing is immense and permanent.”

The Second World War came and was also spent in Italy; to move the whole household would have been difficult, and he had assurances that his age and eminence would be respected. But many of the treasures of I Tatti were hidden, and at one point he and Nicky went into hiding. The invalid Mary, over eighty, was left at I Tatti with the nurse.

Mary died in 1945, and the years of the B.B. myth began, the ancient monument to be visited along with the Uffizi and the Pitti—fourteen more years. There were features on him in Time and Life. His Sketch for a Self-Portrait, written to while away the war years, was a great success. He was able to travel until the very last years, he continued to be consulted by dealers, he wrote a regular column for an Italian newspaper till the end. And everybody who was anybody came to I Tatti, to see the legend, to listen to his talk, and—deferentially—to talk back, and if they were pretty women, to be stroked by his cold old hand. “What we must cultivate in old age is the will to be pleased,” he had written as a young man, and life still pleased him.

In these mellow years of extreme age, when the conflicts that had torn him apart had quietened, his attitude to his Jewishness changed. Not surprisingly, in view of the anti-Semitic remarks quoted here from people of his circle and time, part of the persona of the gentleman-aesthete had been that he was a sort of honorary Gentile; he had in fact converted to Catholicism at one point, though the phase was transient. He had always been hostile to German Jews for their snobbery toward the Eastern Jew that he was, and believed that they would have contentedly become Nazis if they had been allowed to. At the end of the Second World War, in 1944, he wrote an appallingly patronizing “Letter to American Jewry,” which fortunately he was dissuaded from publishing. Do not, he advised, stir up envy:

Even if you were as innocent as the angels you could not escape its venom, and you are far from that…. It is the irresponsible wealth, as well as the arrogance in the high ranks of Jewry, that led to the periodical persecutions and massacres…. So you whom Hitler has for years to come reduced to being a thing apart, a stranger in your land, cannot be too modest, too unassuming, too discreet.

This was written to the class that had supplied much of his own wealth. And yet to his family in the States he was utterly loyal; and he cherished his memories of childhood in Lithuania. In his nineties he was able to write of the delight of being among Jewish friends “when we drop the mask of being goyim and return to Yiddish reminiscences, and Yiddish stories and witticisms.”

It was in these last fragile cossetted years that he felt he could find IT again, after the years of being torn apart by marriage and money. IT was “every experience that is ultimate, valued for its own sake. IT is, the moment to which Goethe can say, ‘Stay, stay, thou art so fair’….” Lytton Strachey, who had written so disparagingly of the atmosphere of I Tatti, was at least wrong in saying that Berenson was “without a spark of naturalness or ordinary human enjoyment.” Even in his rages he was an intensely feeling man. But he was deepest into pure enjoyment when he was absorbing the shades of the countryside or standing in front of a picture and looking, looking, looking. He always found food difficult, but he ate with his eyes. Perhaps he never succeeded in getting IT across in terms of “tactile values” and “ideated sensations of contact,” which really just mean “art makes you feel good.” But what aesthetician says more?

“He is probably the world’s last great aesthete,” wrote Newsweek—ridiculous if an aesthete is someone to whom art is a great joy, true if it means someone who tried (not quite successfully) to build up an entire character and life around the feeling of IT. In the introspective writing of his last years, though he granted himself faults and follies, he saw himself as a kind of carefully achieved work of art. Perhaps it is cruel to end then by quoting against him a letter to that irreducible not-me, his wife, who had complained of feeling pain about his adulteries. Try and relinquish such feelings, he wrote, and she would become

a far more interesting, more companionable person…. Hitherto you have been a child, a mere animal, delightful and sustaining and comforting but only, or little more than, as a physical force. Of the deeper realities of humanized people like myself, of people shall I say with souls you would not hear.

Who is qualified to say who has, and has not, the soul?

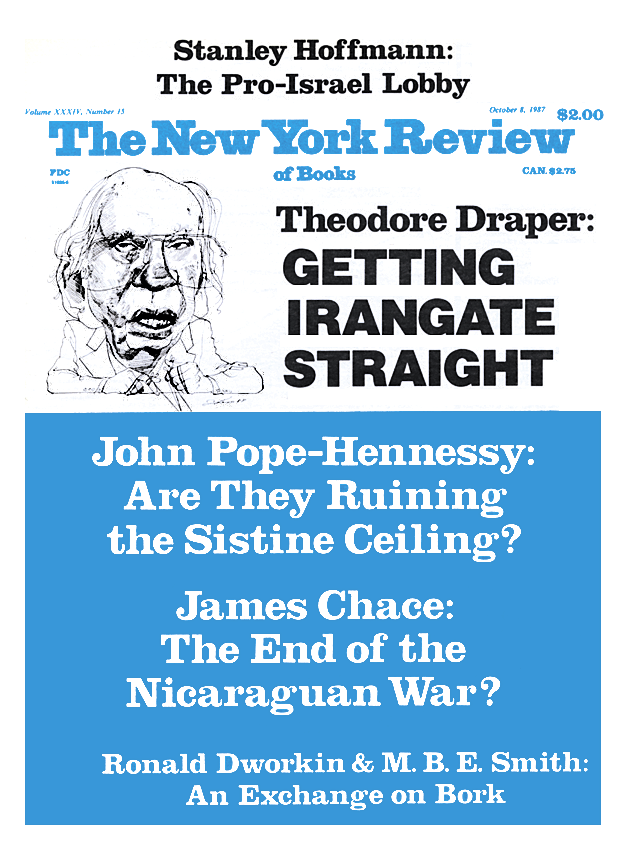

This Issue

October 8, 1987