“We are so critical of our own country that even the president’s criticisms are weak. We know what our problems are.”

—Mikhail Gorbachev in Red Square, May 31, 1988

1.

Moscow—The surmise grows closer to a certainty that the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union would not have been a host so amiably indifferent to every opportunity for taking offense if he were not turning his back on contentions with the United States and looking inward to struggle with the intractabilities of Russian history.

He has, after all, inherited a structure of government very much in the style of the iron regime of Czar Nicholas I. Stalin could be distinguished from the more arbitrary of the Romanovs only to the degree that he swelled their harshness into savagery and shrank the rich voice of prerevolutionary czarist culture down to the dry croakings of his slogan-mongers.

No successor, no matter how determined upon reform, has so far conceived of a way to break the mold of Stalinism except by applications, however more benign, of what are essentially Stalinist methods. There have been periods of freeze and periods of thaw, and each has been the product of a command decision.

We are ten years past the target date Nikita Khrushchev set for catching up with and passing the West, and the Soviet economy has fallen behind South Korea’s. Khrushchev decreed an industrial revolution and now Gorbachev has mandated a democratic revolution, and, as in all the others going back to the liberation of the serfs, the inspiration for useful change has had no source except in one man’s will as served down to the ordinary Russian and never yet satisfactorily digested.

Khrushchev’s failure was the last of Russia’s succession of tragedies, and it is prayerfully to be hoped that Gorbachev’s will not be the next. A Soviet political scientist, with powers of judgment undeflected by his enthusiastic approval of Gorbachev, said recently that his original expectation had been for the economy to advance and freedom to follow in its wake. “But to my surprise,” he said, “we have more freedom than I could have imagined and the economy is pretty much where it was.” Thin as it still is, the air of glasnost is wonderfully exhilarating, but there can be inferred from its current display perhaps a bit too much of the headiness that strong drink can induce on an empty stomach.

The summons “Back to Lenin” has a louder clamor these days than it has had since Khrushchev raised it in the Fifties, and yet Gorbachev’s Lenin is significantly enough different from Khrushchev’s to suggest that the Soviets are no more immune than we Americans to the allurements of periodic reinventions of founding fathers.

The Lenin whose most substantial contribution to socialist theory was to convert it into a police science has no place in the iconography of glasnost’s devotees. Instead, their incense smokes before the image of a speculative philosopher whose notion of the future society is not markedly different from Prince Peter Kropotkin’s benign visions of an anarchist eternity governed solely according to the principles of mutual aid. And yet Leninism accommodates beyond challenge socialism and the dictatorship of the proletariat as incarnate in the single party of its vanguard, and they each will remain closed questions. Gorbachev cannot yet conceive a means to make Russians a better fit for his dreams except by creating better communists. The Soviets have disposed of the contradictions of capitalism by replacing them with the contradictions of communism.

All the same, the fascinations of this dilemma are quite enough to consume the General Secretary’s passions. His taste for adventure is almost all for the domestic and almost none for the foreign and his obvious disinclination to quarrel with the president who was his guest went too far beyond good manners not to imply a fixed purpose to get out of the superpower game whether or not the United States prefers to go on playing it.

There is seldom good reason to trust a statesman’s rhetoric but Gorbachev’s actions are too tangible to make it easy not to think that he means what he says. He is withdrawing from Afghanistan, thank you. Alexei Arbatov, a Soviet Academy of Science disarmament specialist, who has Gorbachev’s ear if not his entire agreement, has persuaded the Vietnamese to pull back a trifle in Cambodia. He can almost casually suggest this future agenda:

—The withdrawal of 20,000 tanks from the Warsaw Pact army as a step toward balancing its forces with NATO’s.

—A reduction of Soviet forces on the Chinese border by two divisions. Two years ago, this gesture would have been taken for a stab at recapturing the China card, but Alexei Arbatov makes it plain that he himself counts the weight of that bit of pasteboard no heavier than a deuce of clubs. And Gorbachev may well assess it with similar disdain and contemplate his pullback not as a gesture to friendship with China but as a solid contribution to the improved health of the Soviet economy.

Advertisement

The inchoate years of international adventurism are, for Arbatov at least, only a bitter thought. “We appointed our recent history,” he reflected, “as though we had been trying objectively to unite the rest of the world against us. We must break out of our global encirclement.”

It is his judgment that the Soviets are encircled not by rival armies but by superior economies. The real specter that haunts Gorbachev is not the counter-revolution but his own mired revolution. He has lost all desire to rove about the stews and fever-swamps of the world and will go back to cleaning his own house. He greeted the President with the sunny detachment of a man with matters on his mind more critical than a mere summit; and the President’s little sermons grew gentler and gentler in the warmth of the smile that endured them. The whole affair has turned into a vast encouragement for all of those everywhere who hope that the discovery that the proper business of the statesman is to leave foreigners alone and do his duty of service to his own citizens might be a revelation not unique for Mikhail Gorbachev but universally contagious.

2.

President Reagan goes home freighted with honors from the revolution. And, if we are to believe the Soviet Foreign Office as much as he seems to for the moment, one of these honors is godfatherdom-in-absentia to two newborn children, a boy named Ron and a girl named Reagana.

The Politburo is not famous for over-much trust in the spontaneity of the masses, and we cannot be sure that these babes were not delivered to the christening bowl by command decision. Even so, this announcement has its tones of the artistically credible, because such evidence as can be said to exist seems to suggest that the Reagan persona was an object of continual pleasure and even occasional delight to ordinary Russians.

It has before now been remarked that the diplomatic genius of America resides in our talent for making peace with countries with which we do not happen to be at war. We have seldom had a president whose execution of these historically irrelevant functions is as adroit as this one’s, and those who groan at the flaccidity of his grip upon issues great and small underestimate his true mastery of the requisite style.

Saint Jerome once expressed his discontent with the early Christians by saying that they were capable of as many roles as there are sins to commit. Our president is, of course, so without sin as to seem unaware of its existence, except as an abstraction, and we could more properly describe him as capable of as many roles as there are charms to dispense.

Cast his part for formal address, and he serves you up Reagan the Renaissance man tripping the green valleys and leaping the treacherous crags of the whole culture of man, contemplating his portfolio of the drawings of the young Kandinsky, sleighriding with Gogol, sorrowing over the memoirs of Anna Akhmatova, thrilling with the discovery of the Uzbek poets, and then, still unwearied, sitting up with the late show to check before correcting the misjudgment of the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences when it withheld its Oscar from Friendly Persuasion and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

But conscript him to the colloquies of give-and-take and he will deliver the Reagan of simple nonsense, a wonderfully worked counterfeit of a dumbness equal to our own. The time comes for questions at the University of Moscow, and one student asks whether he will meet with a delegation of American Indians who have traveled here to submit their century-old complaints. The President replies that, when he gets home, he will be “very pleased to meet them and see what their grievances are or what they feel they might be…. And you’d be surprised—some of them became very wealthy because some of [their] reservations were overlaying great pools of oil, and you can get very rich pumping oil. And so—I don’t know what their grievances might be.”

The windfall profits tax on oil, perhaps? A student asks why he had seen fit to present Mikhail Gorbachev with a list of three hundred Soviet citizens asserting deprivations of their human rights.

“Now I’m not blaming you—I’m blaming bureaucracy,” the President answers. “We have the same type of thing happen in our own country. And every once in a while, somebody has to get the bureaucracy by the neck and shake it loose and say, ‘Stop doing what you’re doing.’ And this is the type of thing and the names that we have brought.”

Advertisement

If he had known what he was doing, he could not have found a key better tuned to the Russian soul. He hates bureaucrats and so do the Russians, from experiences of longer standing and more painful intimacy. One of the oldest traditions in this nation’s history is the voice of some victim of an administrative injustice, vast or little, saying that such things could not be “if the czar only knew.”

Czars come and go, but life keeps to its dreary and inequitable round. And if it is human to think of one’s czar as a man with a heart too warm to permit the excesses of petty officialdom, it is just as human to draw comfort in cherishing the image of the czar who does not know. We might wonder, indeed, whether Reagan’s manner may not appeal to Gorbachev’s constituents more profoundly than to his own.

When Gorbachev and Reagan held their final press conferences, there may have been Americans possessed of a modicum of patriotism who shuddered at the pitiable figure their president cut in contrast with a general secretary who ran the whole range of his piano with impeccable touch on every key. Here was Gorbachev carrying the impression that no sparrow that falls escapes his notice, and, half an hour later, there came Reagan cloaked with every assurance that he lives where no sparrow ever falls anyway.

There was an inquiry about the homeless in America. The President replied that he had heard of people who sleep in the street because they apparently have no place to live, but he has been solaced in that gloomy thought by learning of a “young woman” the police tried to drag from her pavement, who had gone to court to establish her constitutional liberty to freeze all night on the sidewalk of her choice.

Perhaps the Russians do not find this sort of stuff as absurd as some of the rest of us who have less reason than they to think of the state as a universally oppressive nuisance. The President talks their language; he salutes them as the God-fearing people they very probably are in the main; and he blames all their troubles on bureaucrats. And we ought not to be surprised at how cunningly he may have touched the tenderness of their memory of the all-kind czar who did not know.

—June 1 and 2 1988

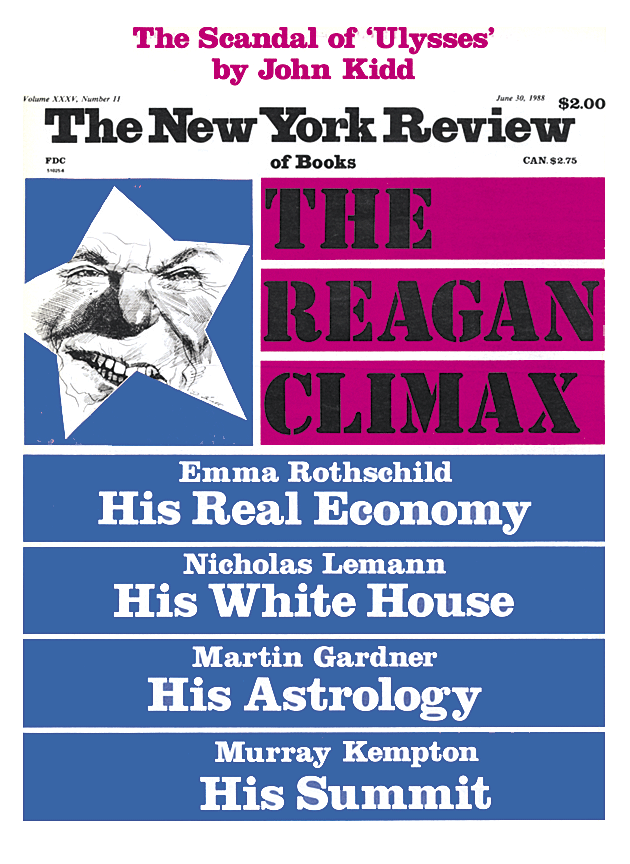

This Issue

June 30, 1988