Western readers are familiar with the intellectual and moral journey made by those who broke with the Communist party after the Thirties. The Moscow show trials, the German-Soviet pact, the Czech coup d’état, the Soviet intervention to defeat Nagy’s revolution in Hungary, are leading moments in recent history and all are marked by further fallings away from the Communist parties under Soviet leadership. One may cease to be a Communist, but having been a Communist leaves ineffaceable marks on the psyche, and the intellectual view of the world is painfully dislocated. What has hitherto been a presupposition of thinking dwindles to a prejudice, one as serious as the belief that the earth is flat or that our fortunes depend upon the positions of the stars and planets at the moment of birth, and after the abandonment of communism it is as though we have been given a new world, a new history, with large features that have hitherto been unnoticed.

I once discussed such matters with a man who had left the Communist party some years before. He had a brother who had fought with the International Brigade and was reported during the war in Spain as “missing, believed killed.” As soon as the man I was talking to left the Party he knew at once, with immediate moral certainty, that his brother had been arrested for some political deviation—no doubt a deviation that could be given the all-purpose label “Trotskyism”—and executed by the Soviet political police. This sudden recognition bore on the question we were discussing—how could men and women who must have known that the show trials were frame-ups, that the Soviet regime employed terror and the threat of it against its own population, that Soviet history was a mass of falsification, how could they have boldly asserted that all these things were lies?

Further, it explained in some measure how men who were sane and apparently honest could go in for deceit on a vast scale. It wasn’t just that some men lied for reasons of state, or out of cowardice. Of course, there were such men, especially those who were members of the apparatus of the Communist parties and functionaries in the Soviet Union. It is rather that the power and charm of a world view transcended the claims of empirical and rational criteria. To choose a slightly absurd example: it was maintained at one of the later Moscow trials that conspirators had lighted bonfires outside the windows of Maxim Gorky (then in favor) in order to exacerbate his bronchitis, and that this was part of a web of conspiracy directed against the safety of the state and the life of the great leader of the world proletariat. There is no doubt that this story was repeated with conviction by many Western Communists. Once the world view was broken, by whatever means—the smiling faces of Stalin, Molotov, and Ribbentrop as they looked at the camera after the signing of the German-Soviet pact, for instance—then much that had been known quite well at a deep level rose to the surface. Those who had left the Party realized that there was much that they had known all along.

The inner drama of Western intellectuals who had been Communists or close fellow travelers was a revulsion from a political and social system that was known only in a schematic way. The Webbs’ book on Soviet Communism is, despite its appearance of erudition, a good example of this. But things were bound to appear differently to East Europeans and to Soviet citizens. A Finn, or a Pole, or a Romanian, or a Ukrainian inside or outside the Soviet Union—these would be familiar with the texture of Soviet life and institutions and would not, if they happened to become Communists, be seduced by the vision of a noble and humane society; nor, if they left the Party, would they pass through the same kind of inner revolution.

The testimony of Aleksander Wat about the perceptions of Polish leftists is fascinating in showing the differences between the experience of Eastern European and Western intellectuals, though this isn’t in the end the main theme, or even an important theme, in My Century. The book is illuminating, though often baffling in its complexity, for the Western reader. But it is addressed through Czeslaw Milosz primarily to an East European audience, above all to Poles and Russians. How completely different Wat’s outlook is from that of people in the West is brought out by the very slight importance given to German National Socialism in his account. The Great Beast is the Soviet system; National Socialism is a “provincial” (the word is Wat’s) phenomenon. He seems to edge away from this view late in the book, but in the main National Socialism does not for him represent a fascination and a horror.

Advertisement

Wat first became known in Poland as a Futurist (or, as he himself preferred to put it, Dadaist) poet. In the late Twenties and the early Thirties he moved close to the Communist party of Poland and became the editor of its best known publication, The Literary Monthly. In the late Thirties the Communist party of Poland became an object of suspicion to the Comintern and the Soviet government, and in 1938 it was dissolved. Many leading members were summoned to Moscow and were there murdered by the political police. At about that time Wat seems to have moved away from the Communist party, though without discarding his general left-wing outlook. Certainly, his moving away from the Party was not for him a great traumatic experience that turned him upside down. (His great experience, his conversion to Christianity, came later.) He had no romantic feeling for the Soviet Union or for the Polish Communist party and in what he writes about the Polish regime after Pilsudski there is little rancor. When he was imprisoned by the Polish government and The Literary Monthly was closed down it was not a severely painful time for him; the then Polish regime seems to have had a tenderness for the intelligentsia and although anti-Semitic feelings were widespread among the ruling groups Wat’s being Jewish seems not to have shaped official attitudes toward him.

After the German-Soviet partition of Poland, Wat, with his wife and son, fled to the east. In the confusion of the time he was separated from his family. Wat was imprisoned in Lwow; his wife and son were deported to Kazakhstan. The account of his life in a series of Soviet prisons—Lwow, Kiev, the Lubyanka in Moscow and Saratov—is the heart of the book. His descriptions of the crowding, the privations, the interrogations, the senseless pedantry of the prison administration, the activities of the informers, the barbaric punishments, are all of them sadly familiar. What is remarkable is the portraits of prisoners, jailers, Chekists, civilian officials, and others. Apart from the Poles and a few other ethnic groups from outside the Soviet Union, practically all the different Soviet peoples were to be found in the prisons. There were Russians, Ukrainians, Kazakhs, Uzbeks, Tartars, men of every social level and every kind of occupation, from high officials to simple peasants; for in those terrible years a high proportion of the Soviet people was in and out of prisons and camps.

It was in Saratov that his inner conversion to Christianity took place. In 1941 he was released from prison and worked in Alma-Ata for a time for the Polish delegation to the Soviet government. Then, when Stalin broke off relations with the Polish government and set up a government of Polish opportunists and Quislings, he was deported to Kazakhstan, where he organized resistance to an attempt by the NKVD to make the Poles take out Soviet citizenship. Again he was, with his wife (his son showed signs of tuberculosis), imprisoned, and they were kept in the Soviet Union after their release. Finally, in 1946, the Wats returned to Poland, where he was at first welcomed and given literary work, then, after 1949, persecuted; then, when Gomulka came to power, he was restored to favor. After 1959 he went into permanent exile, first in France, then in the United States, and finally in France again. He died in Paris in 1967.

We owe My Century to the curious circumstances of his illness. For some years after the war Wat suffered from acute, almost intolerable, pain from a burst blood vessel in the brain. There was a limit to what painkilling drugs could do for him and the doctors hit upon the idea of providing him with some kind of distraction; and it is to this idea that we owe My Century. From the beginning of 1965, when Wat was in Berkeley, California, Czeslaw Milosz would talk to him several times a week about his past; and the result, edited a bit but not severely, is My Century. The direct aim and intention was to relieve the terrible pain and make life easier for Wat. But as Milosz notes, the intrinsic interest of the material was such that recording it became a second reason for the sessions. Milosz puts it well:

I quickly realized that something unique was transpiring between us. There was not a single other person on the face of the earth who had experienced this century as Wat had and who had the same sense of it as he…. What matters here is a cast of mind, a culture typical of a single geographical area and social class, not to be found among the Russians, French, or Americans—specifically, the culture of the Polish intelligentsia…. Let’s put a finer point on it, then: not only was Wat a member of the intelligentsia, but he was also an intellectual, educated in philosophy, and his Jewish origins made for a valuable shading, one that provided him with a certain distance on Polish ways; moreover, he was a member of the Writers’ Union for many years, and, further, he was a poet…. No one in his generation, I thought, was leaving historians a gift of this sort, in this field. That Wat had survived bordered on the miraculous, and so I thought it an honor to serve as a medium in those odd séances.

In his characterization of the Communist mentality as he came across it in others and as he found it in himself, there are two typical moments. First, in talking to comrades about the Moscow trials:

Advertisement

I would ask them, “So is everything clear to you now?” And they would answer, “Yes, it is, but we can’t walk away from it. That’s out entire youth.” Communism proved how incredibly hard it is to walk away from one’s youth when that youth was some sort of high point, a period of unselfishness, a beautiful way of life.

Then he tells us that he was never really a Communist or a Marxist (he seems never in fact to have held a Party card); he was rather “a mad fanatic, a sectarian.” He likens his position in relation to communism to Simone Weil’s in relation to Catholicism—that he misinterprets Simone Weil doesn’t here matter, though it is important not to add to the many current misconceptions about her.

I was afraid of infecting it [communism]. I could feel the burden I carried within myself as a literary man, a poet—the burden of the old capitalist bourgeois decadent Adam. Bourgeois decadence. And I was afraid of causing infection. Just as they’re afraid to send satellites to Mars so as not to cause any viral infection there. Just as Simone Weil was afraid of converting, so as not to bring her Jewishness into the Church.*

“The main thing is how a person stands up to prison.” Thus Wat. He thought he only really learned how to be a prisoner in the Lubyanka. Learning this is not so much a matter of acquiring skills, not even acquiring some variety of the virtue of prudence. The first lesson to be learned is that you are not autonomous and this makes the separation from others, those one has left behind, hard, as though a limb had been amputated. One has to learn to endure what Wat calls “the paradoxes of time.” These occur when, as above all in the Lubyanka, the prisoner is absolutely walled off from the world in a way that wasn’t true of Polish prisons before the war, for they resembled rather the prisons in Dickens, the Fleet or the Marshalsea, where there was a constant coming and going between the prison and the outside world. When the paradoxes of time prevail

the present becomes incredibly distended, expanded like an accordion, while the time behind you, the past, contracts. It seems that the days you have behind you, the past, are only a single day, that time contracts, has little content, whereas the time you have ahead of you is a wasteland, totally terrifying.

Also, there seem often to have been in prison good men, exemplary characters, capable of sweetening through their conversation and demeanor all that went sour in the relations between the members of a cell. Wat pays a tribute to Jan Hempel, who in the end, contrary to Wat’s expectations, proved to be a strengthener, a healer. He remained, strangely, like some other Party prisoners, devoted to the Soviet cause. Wat writes that, contrary to what one might have thought of Hempel before he was encountered in prison, there was suddenly

an enormous contrast—the calm, the majesty, the goodness that he radiated, the calm concentration that was the source of the goodness he radiated. He taught us not only how one should talk and act during an investigation but also how to behave in prison…. He was always reconciling people, talking them around.

And yet it was this man who, totally captivated by one side of Stalinism, woke up in the night and cried out: “Two blast furnaces have just been fired in Magnitogorsk.”

One of the striking things about Wat’s treatment of people is his absolute justice. That a given man is a Stalinist, an anti-Semite, an NKVD colonel, doesn’t color or determine the treatment he will receive from Wat. Even those who are bad, or partly bad, are rarely savaged by his pen. He is especially fascinated by all he observed in the physical demeanor and character of Russians that brings to mind the old Russia, the Russia of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, of Gogol and Turgenev. His sense of old Russia surviving was so strong one has the impression that the population during World War II and later came out of the past. There is the carapace forged by Stalin; but underneath it nineteenth-century Russia persists.

Wat was always sensitive to religious atmospheres. He was greatly struck by the piety of the Ukrainians he encountered in prison. As a Jew, he felt excluded from a religious community to which he would have liked to belong. They sang every day hymns to Mary while he lay in his corner. His background as a Jew was not marked by a great devotion to Judaism. His father was deeply religious but nonobservant. All the same, the young Aleksander absorbed much from the Jewish life around him. He loved the High Holidays and derived from them a sense of the sacral “incomparably higher than the Christians’.”He loved the sight of the young Hassids with their pale angelic faces. But his family inhabited a border region between Judaism and Catholicism. An old family servant to whom he was devoted used to take him to Vespers, which much affected him. A branch of the family had produced a priest, Canon Luria, of Vienna. We see him then with a strong religious sense not tied to any special credal formularies, a religious temperament captivated by Marxism as a generous young man and as a poet and given depth by his excruciating experiences in the prisons of Stalin’s Russia.

It is as hard to write about Wat’s conversion to Christianity as it was for Wat to explain himself, to describe the crucial experience that took place one night in the prison at Saratov. He was starving—they had had a little bread, and this reminded him of the time when his nurse had upbraided him for throwing away a piece of bread; and he then meditated on the theme of the sacredness of bread. This, he thought, was felt by all the inhabitants of the cell. “We ate that bread as if it were the Host. Even Josek, the degenerate, the product of atheism at its worst, ate his bread with a sense of the sacred.” Then Wat had bad diarrhea and a high temperature. “I was practically nothing but skin and bone.” When he was unable to sleep because of the perpetually burning light bulb, something like a vision began.

I saw the devil. Well, I saw a devil with hooves, the devil from the opera. I really did see him—it must have been a hallucination from hunger, but not only did I see him, but I could almost smell the brimstone. My mind was working at terribly high revolutions. It was the devil in history.

And I felt something else, that the majesty of God was spread over history, over all this, a God distant but real. I can’t decipher it fully, I can’t remember it all, but it was so actual, so sensual, as if the devil was in my cell, the ceiling of the cell was lifted away, and God was above it all. It was all straight from commonplace religious folk art. I don’t know. I didn’t see God, because God did not even actually show himself to Moses. God is blinding, but I did see that God—now I can say it—had a beard. The God of iconography. And a devil with hooves.

. . .

It was then I began to be a believer.

He tries hard to work out why the devil should have been associated with the moment of conversion. He thought there was something bad about his conversion. He even says that what the devil represented “perverted the experience.” And yet,

Everything was one that night. The main feeling was the feeling of the oneness of the experience and my oneness with it. Before then I had felt mostly discord within myself, but that night I had such a feeling of monolithic unity, of a sort I was never to experience again in my life. As if I only became myself at that moment. That night I truly was one, one and indivisible. It was a very long night. That night certainly transformed me and also the way I acted in prison. I have the impression that it was only after that night that I became human and was able to live in society with people. I had changed; I had truly changed. I changed my attitude toward my fellow prisoners, and I thought less about myself…. Something had turned around and, for all my grief, I had peace.

But why and in what way was this profound experience treated by Wat as a conversion to Christianity? Milosz feels bound to question him about this and receives the following reply:

What other form could it take? Judaism really is passé as a religion. Judaism did its part and ended in Christianity…. [In my youth] I read a lot. I read the theologians; I read the Church Fathers when I was young—I was very interested in that…. I read all of St. Thomas’s Summa when I was young, and in Latin besides…. And so there’s nothing odd about its [the conversion] being well prepared in advance.

Perhaps to understand the conversion one has to take the entire text of My Century as the illuminating context. What one would think a priori to be Wat’s greatest stumbling block, his Jewish origins, seems not to have been of much account. Certainly, it never crosses his mind that he is an apostate, or, if he knows that this is technically true, he doesn’t accept in any way the common implications of treachery and disloyalty to an ancestral faith.

Plainly Wat is a man of great complexity and depth. He grasps issues through the intuition of a poetic sensibility; he is in no way a rationalist. All the same, the picture he gives of Poland before 1940 and of the world of the prison and of the many types of human being who made up the populations of the jails, both captives and captors, during the years of war is of deep interest for the historian. What Solzhenitsyn did for the camps, Wat has done for the prisons.

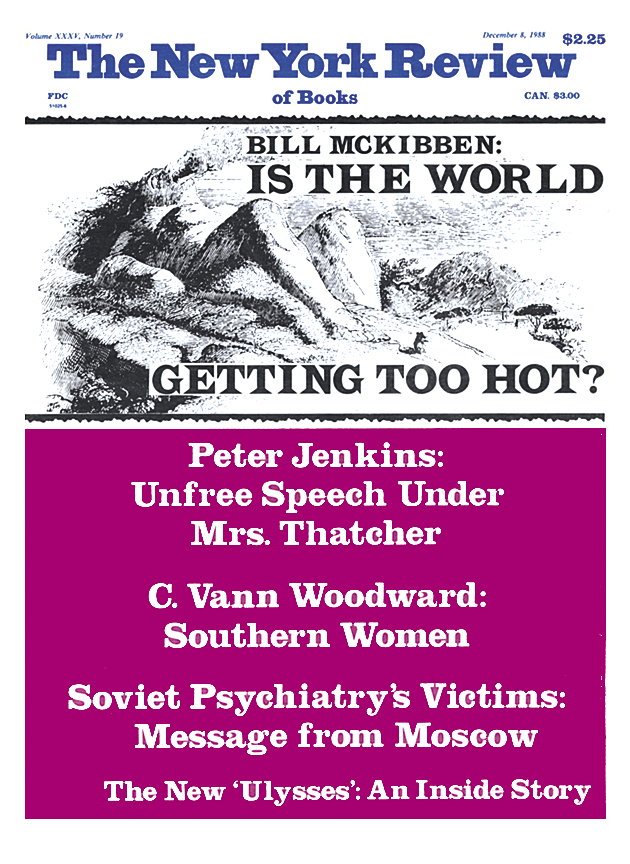

This Issue

December 8, 1988

-

*

Simone Weil had no Jewishness to bring into the Church. This was never for her a motive against conversion. Her objection to the Church was precisely its Jewishness, its insistence on continuity with Israel. She would have preferred that Plato be the Old Testament. ↩